Nov 15, 2017 | APSA, Foreign Affairs, Race, Social Policy

Post developed by Catherine Allen-West

There is a long, documented history of large opinion gaps along racial/ethnic lines regarding U.S. military intervention and humanitarian assistance. For example, some research suggests that since minorities are most likely to bear the human costs of war, African Americans and Latinos might be more strongly opposed to foreign intervention. Additionally, research conducted during the Iraq war found that the majority of African Americans didn’t support the war effort because they believed that they would be the ones called upon to do the “fighting and dying” and that the war would tie up resources typically used for domestic social welfare programs, programs upon which the group depends.

One obvious explanation for these opinion gaps is simple group interest. Americans are more likely to intervene to protect the lives and human rights of victims of humanitarian crises or genocides when the victims are “like us” and this narrow racial or ethnic group interest may be what drives racial/ethnic differences in support for foreign intervention or immigration policy in the U.S. This is important because public support for military and humanitarian interventions is crucial to not only the quantity of aid but also its quality and effectiveness.

But this simple in-group, material interest explanation doesn’t always hold up empirically. African Americans were more protective of the rights of Arab Americans after 9/11, even though they perceived themselves to be at higher risk from terrorism.

In a new paper, presented at the 2017 APSA annual meeting, Cigdem V. Sirin, Nicholas A. Valentino, and José D. Villalobos examine variations in political attitudes across three main racial/ethnic groups — Anglos, African Americans, and Latinos — regarding humanitarian emergencies abroad. The researchers tested these differences using their recently developed “Group Empathy Theory” which states that “empathy felt by members of one group for another can improve group-based political attitudes and behavior even in the face of material and security concerns.” Essentially, the researchers predict that a domestic minority group can empathize with an international group experiencing hardship, even when the conflict doesn’t involve the domestic group at all and when extending help oversees is costly.

The researchers tested their theory with a national survey experiment that assessed support for pre-existing foreign policy attitudes about the U.S. responsibility to protect, foreign aid, the U.S. response to the Syrian civil war, as well as the Muslim Ban proposed by Donald J. Trump.

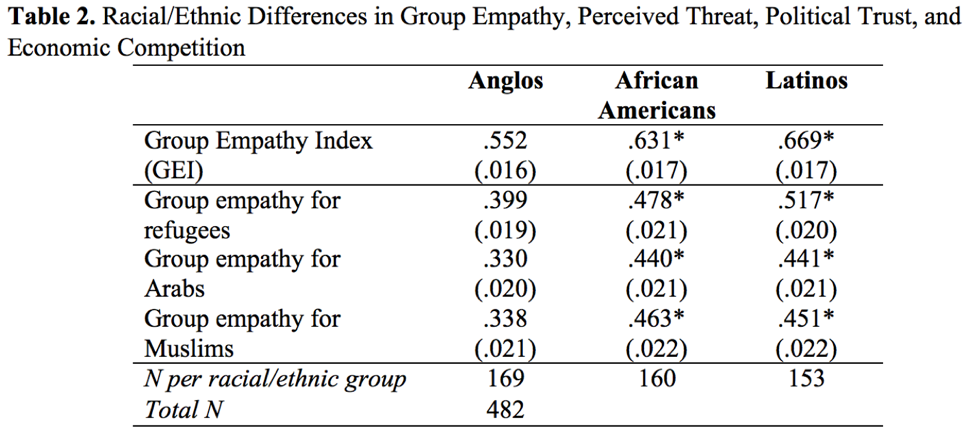

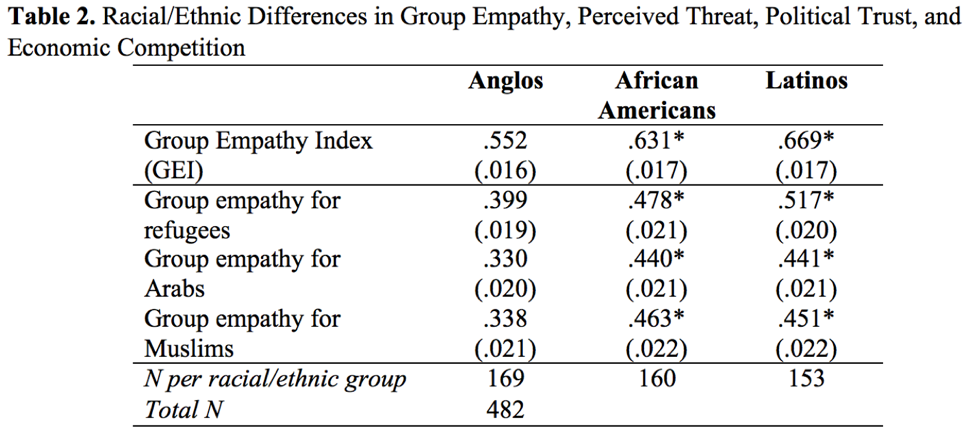

First, they measured levels of group empathy and found that African Americans and Latinos both display significantly higher levels of general group empathy and support for foreign groups in need.

Next, to measure opinions about the U.S. ability to protect, they provided participants with a pair of statements about the role the U.S. should plan in international politics. The first statement read: “As the leader of the world, the U.S. has a responsibility to help people from other countries in need, especially in cases of war and natural disasters.” The second statement was the opposite — denouncing such responsibility to protect. Their results show that African Americans and Latinos are likely to attribute the U.S. higher responsibility to protect people of other countries in need as compared to Anglos. Furthermore, when asked about their opinion on the amount of foreign aid allocated to help countries in need, Latinos and African Americans were more strongly in favor of increasing foreign aid and accepting Syrian refugees than were Anglos.

The researchers further examined potential group-based difference in policy attitudes regarding Trump’s controversial “Muslim ban” which called for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States. Again, both Latinos and African Americans exhibited significantly higher opposition than Anglos to the exclusionary policy targeting a specific group solely based on that group’s religion.

Further analyses also supported the researchers’ claims that group empathy is a significant mediator of these racial gaps in support for humanitarian aid and military intervention on behalf of oppressed groups oversees.

This research brings into focus some of the dynamics that shape public opinion of foreign policy. Given the role of the public in steering U.S. leadership decisions, especially as the current administration seeks to implement deep cuts to foreign aid, investigating the role that group empathy plays in public responses to humanitarian emergencies has important broader implications, particularly concerning U.S. foreign policy and national security.

Jun 23, 2017 | Foreign Affairs, International

by Catherine Allen-West

Political economists have long debated the causal relationship between good institutions—such as technocratic, Weberian bureaucracies—and economic development. Whereas some insist that good institutions must precede economic development, others assert that it is economic success that eventually leads to good institutions. So who’s right and who’s wrong?

Yuen Yuen Ang Faculty Associate at the University of Michigan’s Center for Political Studies answers this question using a novel, dynamic approach in a chapter entitled Do Weberian Bureacracies Lead to Markets or Vice Versa? A Coevolutionary Approach to Development. The chapter recently appeared in an edited volume, States in the Development World, that is the final product of a series of international workshops on state capacity hosted by Princeton University. The chapter is also included in the Working Paper Series of Stanford University’s Center for Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL).

Development as a Three-Step, Coevolutionary Sequence

Ang injects a novel perspective into this long-standing debate. She argues that development unfolds in a three-step coevolutionary sequence:

Harness weak institutions to build markets ➡️ emerging markets stimulate strong

institutions ➡️ strong institution preserve markets.

In this chapter, Ang demonstrates this argument using a historical comparison of three local states in China. She traces the mutual adaptation of state bureaucracies and industrial markets from 1978 (beginning of market reform) through 1993 (acceleration of market reform) to the present.

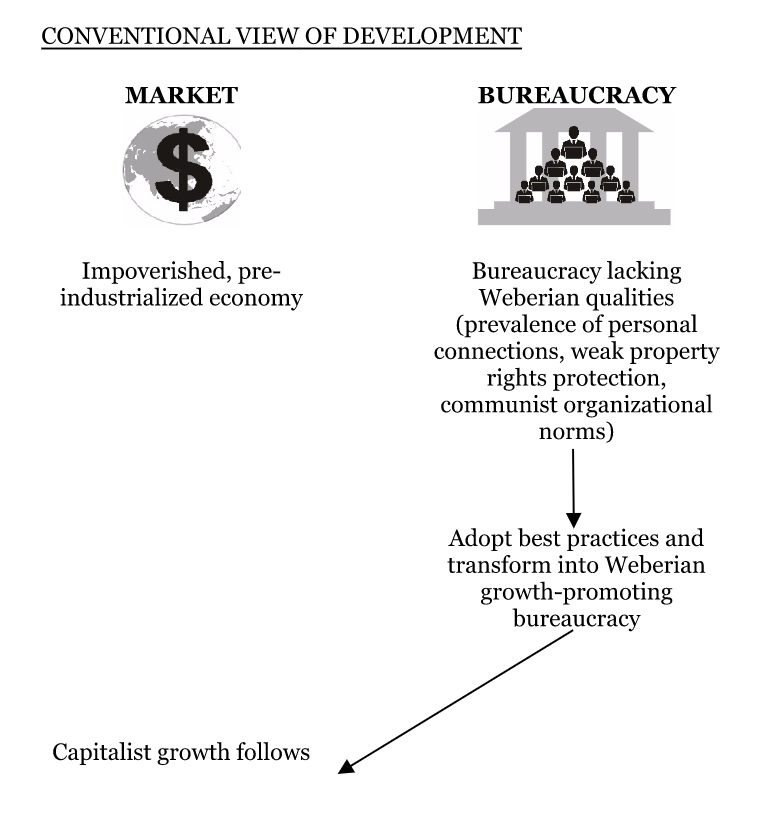

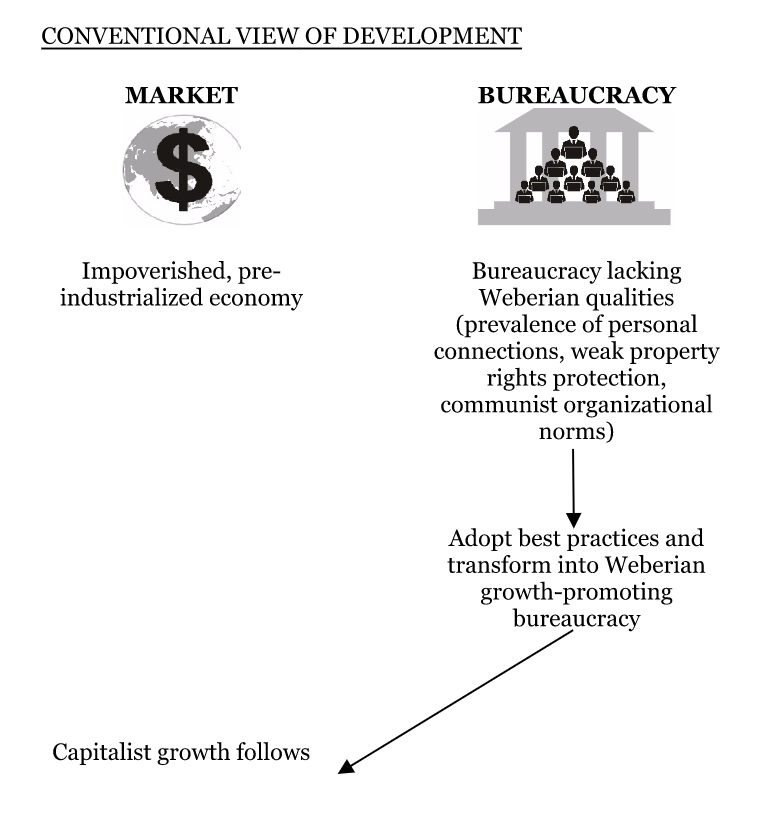

The political economies of all these locales have undergone radical transformation over the past four decades. According to the conventional view of development this process must have occurred by first establishing a fleet of new bureaucracies rather than relying on any existing systems. The process is depicted here:

Ang, however, reveals a surprisingly different—non-linear—story. She finds that Chinese locales built markets by first mobilizing the preexisting bureaucracy, left over from the Maoist era, to attract capitalist investments through distinctly non-Weberian modes of operation: non-specialized and non-impartial. Normally, features that violate Weberian best practices are dismissed as “weak” or “corrupt.” Yet weak institutions, Ang argues, are precisely the raw materials for building markets from the ground up.

From there, Ang says, the process of development continued. Once local markets took off, the emergence of markets altered the preferences and resources of local state actors. These changes led local governments to replace earlier unorthodox practices with more Weberian practices that serve to preserve established markets. Ang’s three-step coevolutionary sequence is summarized in the figure below.

Market-Building ≠ Market-Preserving

Ang’s theory of development draws a sharp distinction between the institutions that bolster emerging as opposed to mature markets, which she calls “market-building” and “market-preserving” institutions respectively. Thus far, existing theories have focused exclusively on “market-preserving” institutions. Ang calls attention to the neglected variety of “market-building” institutions.

This chapter offers a preview of Ang’s broader work, contained in her book, How China Escaped the Poverty Trap. Her book further unpacks the three-step coevolutionary sequence of development, with evidence not only from China but also other national cases (Europe, the U.S., Nigeria). It also details the distinct fieldwork strategies and analytic methods that she developed to map coevolutionary sequences.

Reviews of How China Escaped the Poverty Trap recently appeared in the Straits Times, Foreign Affairs, and World Bank Development Blog. Yongmei Zhou, the Co-Director of the World Development Report 2017, writes in her review:

“The first takeaway of the book, that a poor country can harness the institutions they have and get development going is a liberating message. Nations don’t have to be stuck in the “poor economies and weak institutions” trap. This provocative message challenges our prevailing practice of assessing a country’s institutions by their distance from the global best practice and ranking them on international league tables. Yuen Yuen’s work, in contrast, highlights the possibility of using existing institutions to generate inclusive growth and further impetus for institutional evolution.”

It is extremely promising that the development establishment questions its long-standing belief that conventionally good/strong institutions, benchmarked by Western practices, must be in place for markets to grow. Tremendous room for alternative methods of growth promotion opens up once academics and policymakers entertain the possibility that existing institutions in developing countries, even if they violate best practices, can be used to kick-start markets, as Professor Ang’s research reveals.

References

Ang, Y.Y. “Do Weberian Bureaucracies Lead to Markets or Vice Versa? A Coevolutionary Approach to DevelopmentM.” Chapter in Centeno, Kohli & Yashar (Eds.), States in the Developing World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Ang, Y.Y. How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, Cornell University Press, Cornell Studies in Political Economy, scheduled for release on September 6, 2016.

Ang, Y.Y. “Beyond Weber: Conceptualizing an Alternative Ideal-Type of Bureaucracy in Developing Contexts,” Regulation & Governance, 2016.

Mar 17, 2017 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

by Christopher Fariss and Kristine Eck

Christopher Fariss, University of Michigan and Kristine Eck, Uppsala University

Debate persists inside and outside of Sweden regarding the relationship between immigrants and crime in Sweden. But what can the data actually tell us? Shouldn’t it be able to identify the pattern between the number of crimes committed in Sweden and the proportion of those crimes committed by immigrants? The answer is complicated by the manner in which the information about crime is collected and catalogued. This is not just an issue for Sweden but any country interested in providing security to its citizens. Ultimately though, there is no information that supports the claim that Sweden is experiencing an “epidemic.”

In a recent piece in the Washington Post, we addressed some common misconceptions about what the Swedish crime data can and cannot tell us. However, questions about the data persist. These questions are varied but are related to two core issues: (1) what kind of data policy makers need to inform their decisions and (2) what claims can be supported by the existing data.

Who Commits the Most Crime?

Policymakers need accurate data and analytical strategies for using and understanding that data. This is because these tools form the basis for decision-making about crime and security.

When considering the reports about Swedish crime, certain demographic groups are unquestionably overrepresented. In Sweden, men, for example, are four times more likely than women to commit violent crimes. This statistical pattern however has not awoken the same type of media attention or political response as other demographic groups related to ethnicity or migrant status.

Secret Police Data: Conspiracy or Fact?

In the past, the Swedish government has collected data on ethnicity in its crime reports. The most recent of these data were analyzed by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention’s (BRÅ) for the period 1997-2001. The Swedish police no longer collect data on the ethnicity, religion, or race of either perpetrators or victims of crime. There are accusations that these data exist but are being withheld. Such ideas are not entirely unfounded: in the past, the Swedish police have kept secret—and illegal—registers, for example about abused women or individuals with Roma background. Accusations about a police conspiracy to suppress immigrant crime numbers tend to center around the existence of a supposedly secret criminal code used to track this data. This code is not secret and, when considered, reveals no evidence for a crime epidemic.

For the period of November 11, 2015 through January 21, 2016 the Swedish police attempted to gauge the scope of newly arrived refugees involvement in crime, as victims, perpetrators, or witnesses. It did so by introducing a new criminal code—291—into its database. Using this code, police officers could add to reports in which an asylum seeker was involved in an interaction leading to a police report. Approximately 1% of police reports filed during this period contained this code. It is important to note here that only a fraction of these police incident reports actually lead to criminal charges being filed.

The data from these reports are problematic because there are over 400 criminal codes in the police’s STORM database, which leads to miscoding or inconsistent coding. Coding errors occur because the police officers themselves are responsible for determining which codes to enter in the system. The police note that there was variation in how the instructions for using this code were interpreted. The data show that 60% of the 3,287 police reports filed took place at asylum-seeker accommodation facilities, and that the majority of the incidents contained in these reports took place between asylum seekers. Are these numbers evidence of a crime epidemic?

Is there any Evidence for Crime Epidemic in Sweden?

If asylum-seekers are particularly crime-prone, then we would expect to see crime rates in which they are overrepresented relative to how many are living in Sweden. Sweden hosted approximately 180,000 asylum-seekers during this period and the population of Sweden is approximately 10 million. Therefore, asylum-seekers make up approximately 1.8% of the people living in Sweden, while 1% of the police reports filed in STORM were attributed to asylum-seekers.

While the Code 291 data are problematic because of issues discussed above, the data actually suggests that asylum seekers appear to be committing crime in lower numbers than the general population and does not provide support for claims of excessive criminal culpability. There were four rapes registered with code 291 for the 2.5 month period, which we find difficult to interpret as indicative of a “surge” in refugee rape. We in no way want to minimize the impact that these incidents had on the individual victims, but considering wider patterns, we consider a rate of four reports of rape over 76 days for a asylum-seeking population of 180,000 as not convincing evidence of an “epidemic” perpetrated by its members.

There is no doubt that crime occurs in Sweden. This is a problem for Swedish society and an important challenge for the government to address. It is a problem shared by all other countries. There is also no doubt that refugees and immigrants have committed crimes in Sweden, just as there is no doubt that Swedish-born citizens have committed crimes in Sweden as well. But if policy initiatives are to focus on particular demographic groups who are overrepresented in crime statistics, then it is essential that the analysis of the crimes committed by members of these groups be based on careful data analysis rather than anecdotes used for supporting political causes.

The Government of Sweden’s Facts about Migration and Crime in Sweden: http://www.government.se/articles/2017/02/facts-about-migration-and-crime-in-sweden/

Christopher Fariss is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and Faculty Associate at the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan. Kristine Eck is Associate Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University.

Dec 21, 2016 | Current Events, Elections, Foreign Affairs, Gender, Innovative Methodology, Law, Race

Post written by Catherine Allen-West.

Since it’s establishment in 2013, a total of 123 posts have appeared on the Center for Political Studies (CPS) Blog. As we approach the new year, we thought to take a look back at which of these 123 posts were most viewed across 2016.

01. Tracking the Themes of the 2016 Election by Lisa Singh, Stuart Soroka, Michael Traugott and Frank Newport (from the Election Dynamics blog)

“The results highlight a central aspect of the 2016 campaign: information about Trump has varied in theme, almost weekly, over the campaign – from Russia, to taxes, to women’s issues, etc; information about Clinton has in contrast been focused almost entirely on a single theme, email.”

“The results highlight a central aspect of the 2016 campaign: information about Trump has varied in theme, almost weekly, over the campaign – from Russia, to taxes, to women’s issues, etc; information about Clinton has in contrast been focused almost entirely on a single theme, email.”

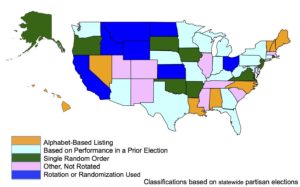

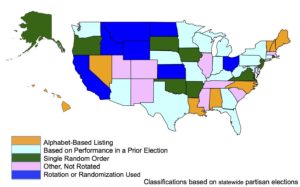

02. Another Reason Clinton Lost Michigan: Trump Was Listed First on the Ballot by Josh Pasek

“If Rick Snyder weren’t the Governor of Michigan, Donald Trump would probably have 16 fewer electoral votes. I say this not because I think Governor Snyder did anything improper, but because Michigan law provides a small electoral benefit to the Governor’s party in all statewide elections; candidates from that party are listed first on the ballot.”

“If Rick Snyder weren’t the Governor of Michigan, Donald Trump would probably have 16 fewer electoral votes. I say this not because I think Governor Snyder did anything improper, but because Michigan law provides a small electoral benefit to the Governor’s party in all statewide elections; candidates from that party are listed first on the ballot.”

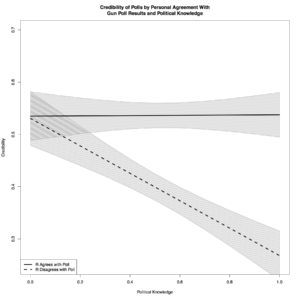

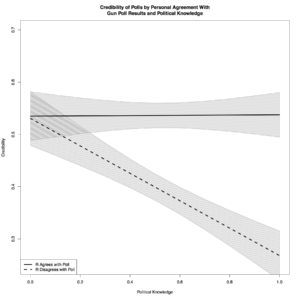

03. Motivated Reasoning in the Perceived Credibility of Public Opinion Polls by Catherine Allen-West and Ozan Kuru

“Our results showed that people frequently discredit polls that they disagree with. Moreover, in line with motivated reasoning theories, those who are more politically sophisticated actually discredit the polls more. That is, as political knowledge increases, the credibility drops substantially for those who disagree with the poll result.”

04. Why do Black Americans overwhelmingly vote Democrat? by Vincent Hutchings, Hakeem Jefferson, and Katie Brown, published in 2014.

“Democratic candidates typically receive 85-95% of the Black vote in the United States. Why the near unanimity among Black voters?”

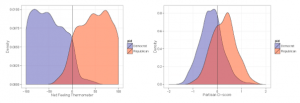

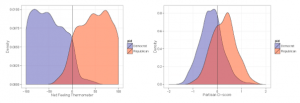

05. Measuring Political Polarization by Katie Brown and Shanto Iyengar, published in 2014.

“Both parties moving toward ideological poles has resulted in policy gridlock (see: government shutdown, debt ceiling negotiations). But does this polarization extend to the public in general?”

“Both parties moving toward ideological poles has resulted in policy gridlock (see: government shutdown, debt ceiling negotiations). But does this polarization extend to the public in general?”

06. What makes a political issue a moral issue? by Katie Brown and Timothy Ryan, published in 2014.

“There are political issues and then there are moral political issues. Often cited examples of the latter include abortion and same sex marriage. But what makes a political issue moral?”

07. Moral Conviction Stymies Political Compromise, by Katie Brown and Timothy Ryan, published in 2014.

Ryan’s overarching hypothesis boils non-compromise down to morals: a moral mindset orients citizens to oppose political compromises and punish compromising politicians. There are all kinds of issues for which some citizens seem resistant to compromises: tax reform, same-sex marriage, collective bargaining, etc. But who is resistant? Ryan shows that part of the answer has to do with who sees these issues through a moral lens.

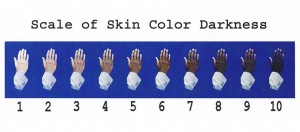

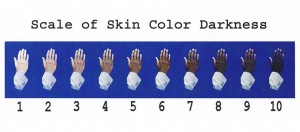

08. Exploring the Effects of Skin Tone on Policy Preferences Among African Americans by Lauren Guggenheim and Vincent Hutchings, published in 2014.

In the United States, African Americans with darker skin tones have worse health outcomes, lower income, and face higher levels of discrimination in the work place and criminal justice system than lighter skinned Blacks. Could darker and lighter skinned African Americans in turn have different policy preferences that reflect their socio economic status-based outcomes and experiences?

In the United States, African Americans with darker skin tones have worse health outcomes, lower income, and face higher levels of discrimination in the work place and criminal justice system than lighter skinned Blacks. Could darker and lighter skinned African Americans in turn have different policy preferences that reflect their socio economic status-based outcomes and experiences?

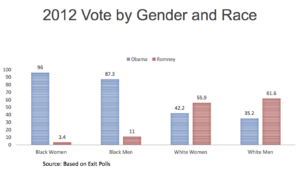

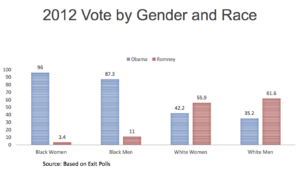

09. What We Know About Race and the Gender Gap in the 2016 U.S. Election by Catherine Allen-West

As of October, the latest national polls, predicted that the 2016 Election results will reflect the largest gender gap in vote choice in modern U.S. history. If these polls had proven true, the 2016 results would indicate a much larger gender gap than what was observed in 2012, where women overwhelmingly supported Barack Obama over Mitt Romney. University of Texas at Austin Professor Tasha Philpot argues that what really may be driving this gap to even greater depths, is race.

As of October, the latest national polls, predicted that the 2016 Election results will reflect the largest gender gap in vote choice in modern U.S. history. If these polls had proven true, the 2016 results would indicate a much larger gender gap than what was observed in 2012, where women overwhelmingly supported Barack Obama over Mitt Romney. University of Texas at Austin Professor Tasha Philpot argues that what really may be driving this gap to even greater depths, is race.

10. How do the American people feel about gun control? by Katie Brown and Darrell Donakowski, published in 2014.

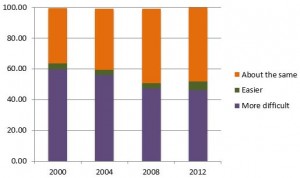

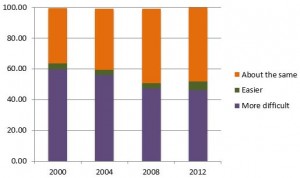

As we can see, the proportion of the public supporting tougher regulation is shrinking over the time period, while satisfaction with current regulations increased. Yet, support for tougher gun laws is the most popular choice in all included years. It is important to note that these data were collected before Aurora, Newtown, and the Navy Yard shootings. The 2016 ANES study will no doubt add more insight into this contentious, important issue.

As we can see, the proportion of the public supporting tougher regulation is shrinking over the time period, while satisfaction with current regulations increased. Yet, support for tougher gun laws is the most popular choice in all included years. It is important to note that these data were collected before Aurora, Newtown, and the Navy Yard shootings. The 2016 ANES study will no doubt add more insight into this contentious, important issue.

Sep 1, 2016 | APSA, Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Catherine Allen-West in coordination with Michael Robbins.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Passive Support for the Islamic State: Evidence from a Survey Experiment” was a part of the session “Survey and Laboratory Experiments in the Middle East and North Africa” on Thursday, September 1, 2016.

On Thursday morning at APSA 2016, Michael Robbins, Amaney Jamal and Mark Tessler presented work which explores levels of support for the Islamic State among Arabs, using new data from the Arab Barometer. The slide set used in their presentation can be viewed here: slides from Robbins/Jamal/Tessler presentation

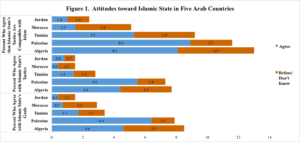

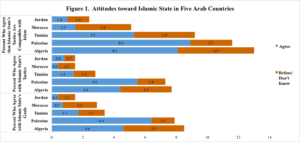

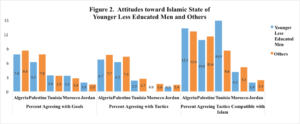

Their results show that among the five Arab countries studied (Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, Palestine and Algeria) there is very little support for the tactics used by Islamic State.

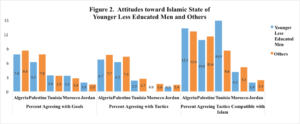

Furthermore, even among Islamic State’s key demographic – younger, less-educated males – support remains low.

For a more elaborate discussion of this work and the above figures, please see their recent post in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog, “What do ordinary citizens in the Arab world really think about the Islamic State?”

Mark Tessler is the Samuel J. Eldersveld Collegiate Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan. Michael Robbins is the director of the Arab Barometer. Amaney A. Jamal is the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton University and director of the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice.

Jul 18, 2016 | Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Linda Kimmel in coordination with Yuen Yuen Ang.

In June, Yuen Yuen Ang, Assistant Professor of Political Science and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate, spoke at a panel on “What Should Tomorrow’s Aid Agencies Look Like?” Jointly organized by the Global Development Network (GDN) and Center for Global Development, the event featured Professor Ang as a winning author of the GDN Essay Competition on “The Future of Development Assistance,” sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The contest invited “original and innovative thinking on development assistance.” An international jury of development experts selected thirteen winners out of 1,470 submissions worldwide.

In June, Yuen Yuen Ang, Assistant Professor of Political Science and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate, spoke at a panel on “What Should Tomorrow’s Aid Agencies Look Like?” Jointly organized by the Global Development Network (GDN) and Center for Global Development, the event featured Professor Ang as a winning author of the GDN Essay Competition on “The Future of Development Assistance,” sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The contest invited “original and innovative thinking on development assistance.” An international jury of development experts selected thirteen winners out of 1,470 submissions worldwide.

(more…)