Post developed by Katie Brown and Yuri Zhukov.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Measuring Rape Culture,” was a part of the Political Methodology theme panel “Big Data and the Analysis of Political Text” on Friday August 29th, 2014.

In August of 2012, two high school football players raped a young woman in Steubenville, Ohio. Instead of intervening, witnesses recorded the incident, posting photos and videos to social media sites. The social media trail eventually led to a widely publicized indictment and trial. Yet while the two teenagers were convicted of rape, coverage of the case nonetheless came under fire for perpetuating rape culture. News outlets displayed empathy for the rapists while blaming the victim.

When the media cover sexual assault and rape, empathizing with the accused and/or blaming the victim may send the message that rape is acceptable. This acceptance in turn could lead to an increase in sexual violence, with perpetrators operating with a perceived sense of impunity and victims remaining silent. Yet there exists no systematic study of the prevalence or effects of the media and rape culture.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate and Assistant Professor of Political Science Yuri Zhukov, along with Matthew A. Baum and Dara Kay Cohen of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, are filling this gap with a systematic investigation of rape culture reporting in the news media through an analysis of 310,938 newspaper articles published between 2000 and 2014.

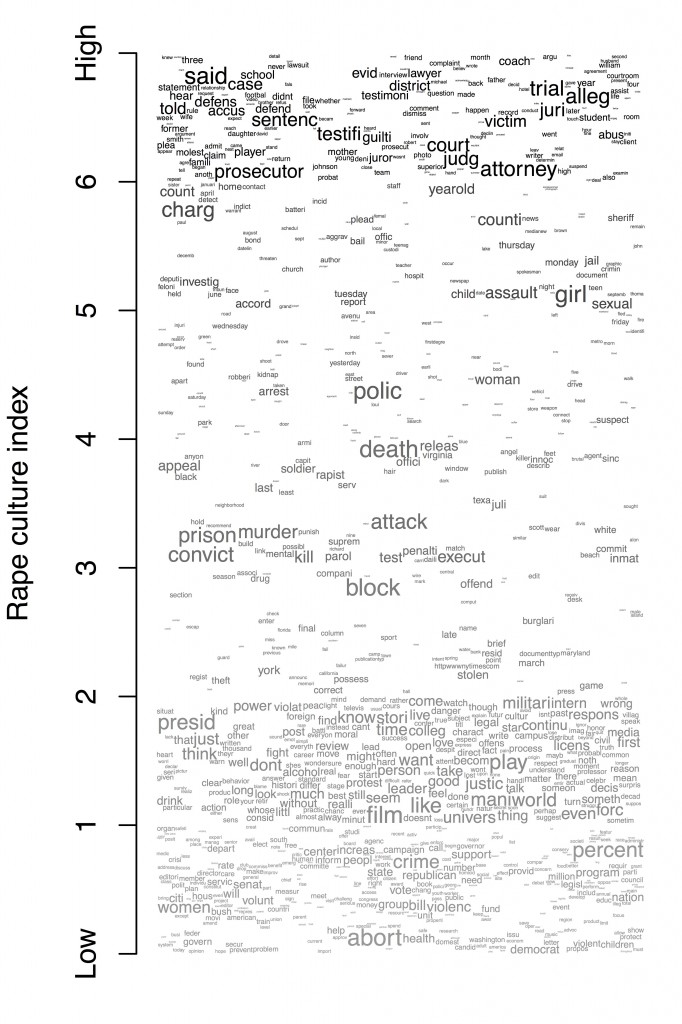

The authors first had to operationalize the concept of rape culture, to date a diffuse term. In addition to perpetrator empathy and victim blaming, the authors added implications of victim consent and questioning victim credibility as fundamental dimensions of the concept. The authors then broke down each of these four categories into more detailed content, resulting in 76 descriptors of rape culture. Trained coders analyzed a random subset of some 13,000 newspaper articles. Zhukov and his colleagues then used these manually coded articles to “train” a computer algorithm to detect rape culture in a previously unseen body of text. The algorithm then assigned each of 310,938 articles an overall score on a 6-point Rape Culture index, with higher scores corresponding to articles with more rape culture language.

While the study offers many provocative and important findings, we will focus on an innovative and startling result. The authors created a word cloud mapped onto the rape culture index.

Articles with scores on the lower end of the index tended to discuss rape in the context of crime in general or domestic politics. Articles in the mid-range tended to discuss it in the context of that particular crime, the fate of the accused, and the response of law enforcement. Articles high on the index tended to be about court proceedings (and refer to the victim as “girl,” especially “young girl”) or to athletic institutions. Based on the word cloud graph, the authors conclude that: “Rape culture is less apparent in the initial stages of a case, when news stories are more focused on covering the facts of crimes,” and “Rape culture is strongest when individual cases reach the justice system.”

The authors find that rape culture is quite common in American print media: over half of all newspaper articles about rape revealed information that might compromise a victim’s privacy, and over a third contained language recognized by the algorithm as victim-blaming, empathetic toward the perpetrator, or both. Contrary to popular belief, preliminary findings suggest that rape culture does not depend on the strength of local religious beliefs, or local crime trends. However, the authors find a strong correlation with local politics and demographics: the higher the female share of the population where an article is published, the less likely that article is to contain rape culture language.