This post was created by Catherine Allen-West, Nahomi Ichino and Noah Nathan.

Political parties across the developed and developing world increasingly rely on some form of primary to select nominees for legislative elections. The candidate selection process within political parties is crucial for shaping the extent to which voters can control elected representatives, as parties are important intermediaries between citizens and government.

The scientific literature has only scratched the surface in examining how primary elections operate in new democracies and what the implications of the system may be, both for the quality of candidates presented to the electorate and for general election outcomes. The process for selecting a candidate varies on several dimensions, including the restrictiveness of the rules for who may seek a nomination and who selects nominees.

In a new paper entitled, Democratizing the Party: The Effects of Primary Election Reforms in Ghana, Nahomi Ichino and Noah Nathan, collaborators in the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan, investigated the impact of recent reforms within one of the two major parties in Ghana that significantly expanded the size of the primary electorate.

Ghana has held regular, concurrent elections for president and a unicameral parliament since its transition to democracy in 1992. The two parties that dominate elections in Ghana’s parliament are the National Democratic Congress (NDC), the current ruling party, and the New Patriotic Party (NPP), the current opposition. The two parties pursue similar policy, but they differ in their ethnic bases of support. Voting is not exclusively along ethnic lines, but, in Ghana, ethnicity remains a strong determinant of vote choice overall.

One reason that Ichino and Nathan looked at primaries in a new democracy is that patronage is prevalent in these settings. The primaries are a contest over who becomes the more important local patron in a given constituency rather than a contest over policy issues and ideology. In these scenarios, voting in primaries can involve extensive vote buying through the distribution of private goods. In Ghana, aspirants (politicians seeking their party’s nomination) woo voters with gifts of flat screen TVs, new motorbikes, payment of school fees for their children and more. This system inherently benefits aspirants with immense personal wealth and the political connections to distribute these goods to the right people. It also disadvantages aspirants who are outsiders who may better represent the interests of the party membership, like women or people from different ethnic groups.

So, given Ghana’s recent reforms that expanded the size of the electorate, Ichino and Nathan argue that this expansion will have positive effects on democratic representation through two changes:

- Vote buying becomes more difficult both logistically and financially due to the sheer size of new electorate.

- The expanded primary electorate will include new voters from groups that have been underrepresented in local party leadership positions.

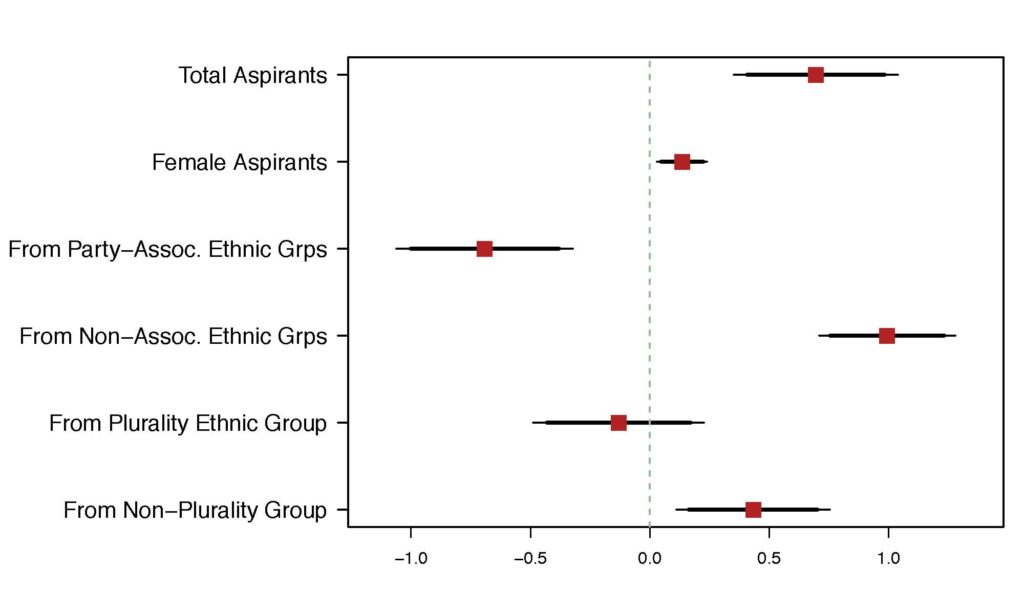

These changes in turn will affect what types of politicians choose to compete in primary elections and the types of politicians who win nominations. In particular, the researchers hypothesize that more female politicians and politicians from groups that are usually excluded from power will compete for nominations and that nominees will be more likely to come from these marginalized groups. Ultimately, a larger pool of people- representing a more diverse distribution of preferences and interests- has a viable path to a nomination, and thus to elected office.

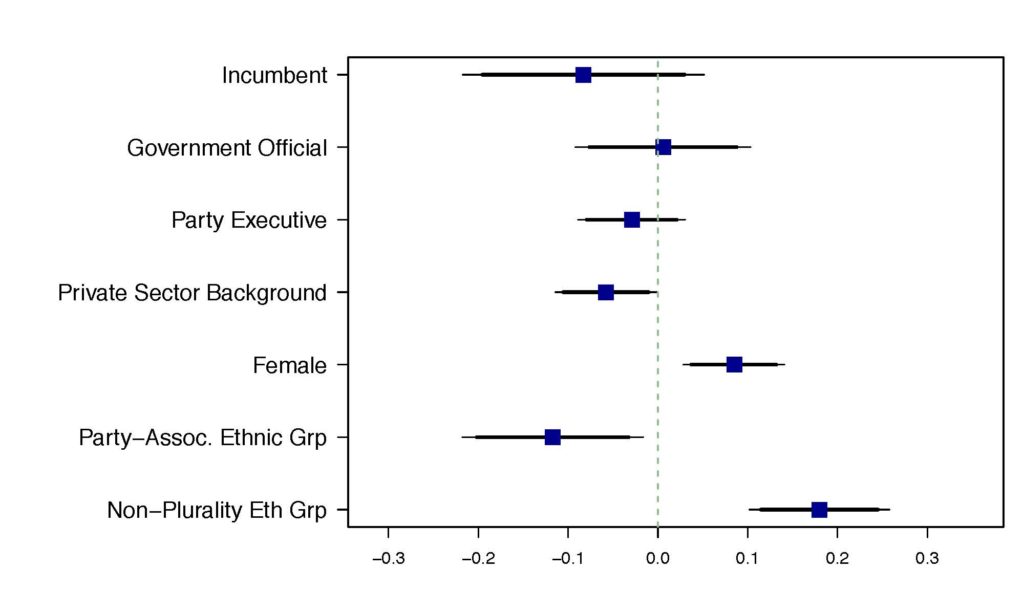

Their results show just that: With the new reforms, the total number of aspirants increased (including women and other ethnic groups) and more of these aspirants went on to become the party nominee. Also interesting to note: the number of aspirants with a private sector background (which indicates more personal wealth to put towards vote buying) decreased significantly.

This figure shows the effects of reforms on the number of aspirants (total, women aspirants only, and then aspirants from different sets of ethnic groups).

Overall, the reforms increased the probability that the nominee will be from a non-plurality (local minority) ethnic group by 18 percentage points on average and reduced the probability that the nominee will be from the party’s core ethnic coalition by 12 percentage points on average.

This figure shows the effects of reforms on the characteristics of the selected nominee (whether that was the incumbent, someone who was a government official, etc.)

The results suggest that, in Ghana, the reforms opened up important positions in the party to previously under-represented groups. This work is important because it advances our understanding of the nature and effects of primary elections in new democracies, contributes to research on institutional reforms that can improve the political incorporation of women, and also shows how internal political dynamics within parties shape the connections between parties and ethnic groups in setting where ethnic competition is prevalent.