ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Electoral Volatility in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes” was a part of the session “Elections Under Autocracy” on Sunday, September 13, 2020.

Until recently, there has been little need to measure the electoral volatility, changes in vote shares between parties, in authoritarian regimes because most conventional authoritarian regimes were either one-party or no-party systems. In general, high levels of volatility are considered to be a sign of instability in the party system and show that the existing parties are unable to build connections with their constituencies.

New research by Wooseok Kim, Allen Hicken, and Michael Bernhard examines the ways that electoral volatility in democratic regimes may be useful for understanding competitive authoritarian regimes.

As a greater number of authoritarian regimes have permitted electoral competition and greater party autonomy, electoral volatility has become more salient. Multiparty elections in competitive authoritarian regimes are different from those in democracies, in that competition is more constrained and incumbents have the ability to manipulate the outcomes.

Electoral volatility can provide clues about the level institutionalization in the ruling and opposition parties, as well as the level of support for the authoritarian incumbent. Low volatility suggests a high level of stability and control in the ruling party institutionalization; high volatility as associated with weak party organizations, weak societal roots, and low levels of cohesion.

The authors tested the relationship between electoral volatility, which is the most commonly used measure of party system institutionalization, and the survival of competitive authoritarian regimes. To do this, they used a dataset that included authoritarian regimes in the post-WWII period that hold minimally competitive multiparty elections with basic suffrage, which are determined using indicators from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem).

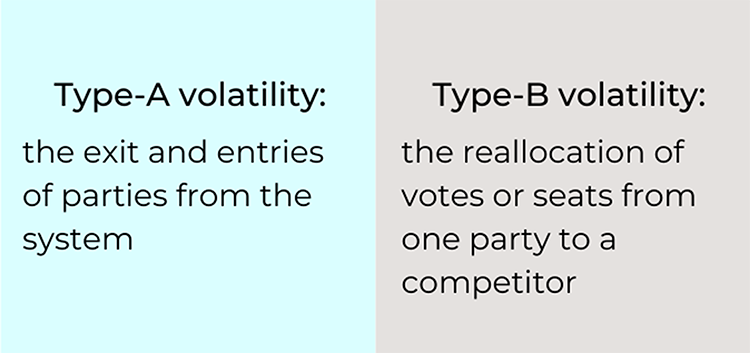

Specifically, the authors measure two types of electoral volatility in competitive authoritarian regimes: type-A volatility and type-B volatility. Type-A is volatility measures the exit and entries of parties from the system. Type-B volatility measures the reallocation of votes or seats from one party to a competitor.

Electoral authoritarian regimes are more stable when they tightly control the party system and the opposition is disorganized. The authors conclude that type-B volatility promotes authoritarian replacement, while type-A volatility is associated with a greater likelihood of a democratic transition. In addition to considering measures of party system institutionalization in authoritarian regimes, future case studies may shed more light on the link between electoral dynamics and outcomes.