Feb 13, 2023 | ANES, expert analysis, National

This post was developed by Ken Kollman and Tevah Platt, based on the talk, “When People Change Their Partisanship, is it Bottom-Up or Top-Down?” that Ken Kollman presented for the Research Center for Group Dynamics Winter Seminar Series on Political Polarization (2023) at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Ken Kollman is the Director of the Center for Political Studies.

Partisanship is sticky. People tend to vote like their parents and to maintain their partisan leanings over time. But to understand partisanship, we need a model that can explain why people change party loyalties when they do. This is what Ken Kollman and John E. Jackson of the University of Michigan Center for Political Studies (CPS) provide in Dynamic Partisanship: How and Why Voter Loyalties Change. The following summarizes their overarching argument.

What is partisanship?

Partisanship is a group-based, shared identity. A classic work from 1960, The American Voter, also out of ISR, describes partisan identity as a long-term, affective, psychological attachment to a political party. According to this famous “Michigan model,” the socially-informed attitudes and values we form early in life durably influence the way we identify with political parties and how we vote.

Kollman and Jackson argue that partisanship has similarities to brand loyalty. It’s relatively stable and habitual, but it’s also evaluative and cognitive. Parties compete for votes and, importantly, for voter loyalty among “consumers” who are considering and comparing candidates and party ideas. Voters “experience” parties in office and in campaigns, and evaluate parties like consumers with products. Yet voting over time for the same party can also become habitual until voters become dissatisfied with what they chose.

What drives partisanship change?

Ronald Reagan often said that he didn’t leave the Democratic party, but the Democratic party left him. The quip encapsulates what Kollman and Jackson find to be the primary answer to the question of what moves partisanship. Two other processes do influence partisan dynamics– changes in people’s political attitudes and their evaluations of the performance of politicians in office – but it’s the behaviors of parties that they find are the greatest contributors to changing partisanship.

- At the micro-level, partisanship is driven by evaluations of parties and politicians who are themselves changing for strategic reasons to try to win office.

- At the macro-level, party polarization is a consequence of elite-level competition for voters, mostly at a national scale– for example, in response to national policies and movements.

In the broader debates about polarization, the stake they claim is that polarization is driven by elite-level competition for power, and not by ordinary people changing their minds about their ideologies or issue positions. It’s top-down, driven by what politicians and their parties do.

How parties compete

A canonical model of party competition came out of the mid-century work of Anthony Downs, who developed a theory of party competition in ideological space. This theory drew a picture of the Democratic and Republican parties converging on the “median voter” the way that ice cream trucks would converge at the middle of a beach to attract the most customers. More complex models admit that political ideology and conflict takes place in multiple dimensions; on the ground, for example, a candidate or party that is moving right on social issues could be moving left on economic policy, perhaps testing out impacts on voters.

A case in point: the language of industrial protectionism (saving factories) was an economically leftward move of the Trump-guided GOP that effectively turned Ohio from purple to red by attracting whites in Northeastern Ohio to the Republicans. Dynamic Partisanship tracks such patterns across the US, the UK, Canada and Australia over more than a half-century, but the overarching trend is that parties are the moving gear in dynamic partisanship. Voters don’t need to be moved, but partisanship can change because voters are reacting to parties that move– and that’s the underlying dynamic.

Partisan trends in the US

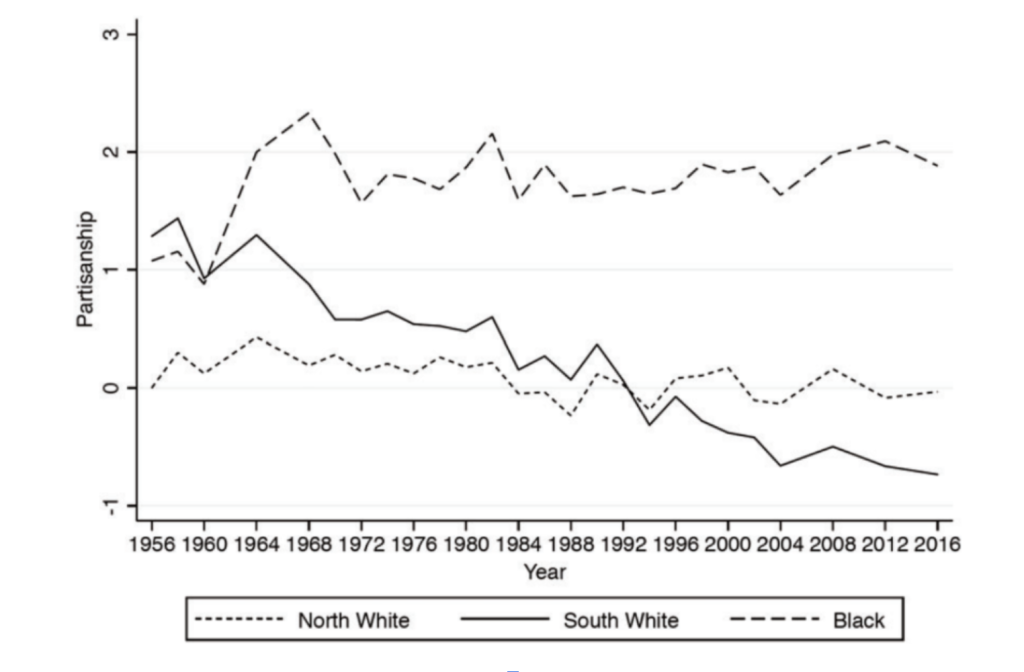

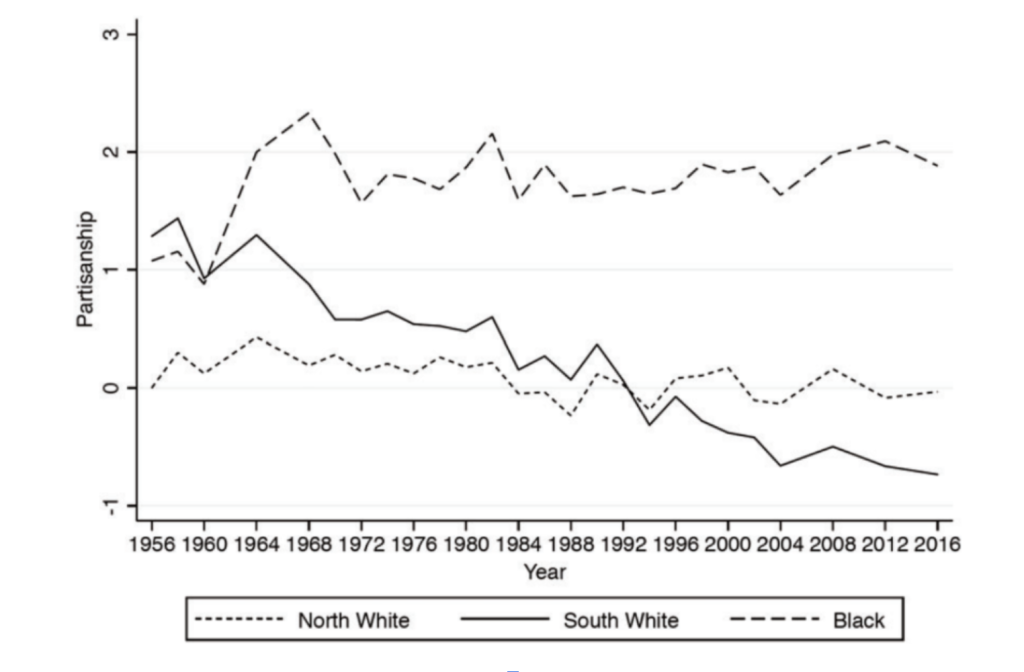

This figure, from Dynamic Partisanship, plots partisanship among three groups of the U.S. electorate– northern whites, southern whites, and African Americans– from 1956 to 2016, with Democratic partisanship increasing on the y axis. There are three distinct patterns:

- Northern white partisanship is the most stable, coming closest to the traditional view of party identification as an unchanging personal attribute;

- The 1964 election, on the heels of the passage of the Civil Rights Act, is a critical turning point in African American partisanship, making a full-point leap and remaining consistently high on the Democratic scale from that time;

- Southern white partisanship shows a strong, gradual trend shifting from moderately Democratic to weakly Republican over 61 years.

The twin phenomena of southern Black voters becoming more Democratic since the 1960s and southern whites becoming slowly more Republican over time represent two of the major tectonic shifts in American society and politics that have occurred in the last half century.

The innovation is that the model used in Dynamic Partisanship can accommodate these divergent patterns– relative stasis, abrupt changes, and gradual changes. For the details and the myriad examples, check out the book.

Dec 2, 2016 | Current Events, Elections, Innovative Methodology

Post written by Lauren Guggenheim and Catherine Allen-West.

In November, a federal court ruled that the Wisconsin Legislature’s 2011 redrawing of State Assembly districts unfairly favored Republicans deeming it an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. This ruling is the first successful constitutional challenge to partisan gerrymandering since 1986. The case will now head to the U.S. Supreme Court—which has yet to come up with a legal standard for distinguishing between acceptable redistricting efforts and unconstitutional gerrymandering.

While there have been successful challenges to gerrymandering based on racial grounds, most recently last week in North Carolina, proving partisan gerrymandering—where the plaintiffs must show that district lines were drawn with the intent to favor one political party over another—is more difficult. One reason is that research shows that even non-partisan commissions can produce unintentional gerrymandered redistricting plans solely on the basis of the geography of a party’s supporters. Also complicating matters are legislatures’ lawful efforts to keep communities of interest together and facilitate the representation of minorities. Because traditional efforts can produce results that appear biased, showing partisan asymmetries—the main form of evidence in previous trials—is not sufficient to challenge partisan gerrymandering in the courts.

However, in recent years, scientists have devised several standards that could be used to effectively measure partisan gerrymandering. In last month’s Wisconsin ruling, the court applied one such mathematical standard called the “efficiency gap“- a method that looks at statewide election results and calculates “wasted votes.” Using this method, the court found that Republicans had manipulated districts by packing Democrats into small districts or spreading them out across many districts, which ultimately led to Republican victories across the states larger districts.

Another method to determine partisan gerrymandering, developed by political scientists Jowei Chen and Jonathan Rodden, uses a straightforward redistricting algorithm to generate a benchmark against which to contrast a plan that has been called into constitutional question, thus laying bare any partisan advantage that cannot be attributed to legitimate legislative objectives. In a paper published last year in the Election Law Journal, Chen, a Faculty Associate at the University of Michigan’s Center for Political Studies and Rodden, Professor of Political Science at Stanford University, used the controversial 2012 Florida Congressional map to show how their approach can demonstrate and unconstitutional partisan gerrymander.

First, the algorithm simulates hundreds of valid districting plans, applying criteria traditionally used in redistricting decisions—compactness, geographic contiguity, population equality, the preservation of political communities, and the protection of voting rights for minorities—while disregarding partisanship. Then, the existing plan can be compared to the partisan distribution of the simulated plans to see where in the distribution it falls. If the partisanship of the existing plan lies in the extreme tail (or outside of the distribution) that was created by the simulations, it suggests the plan is likely to have been created with partisan intent. In other words, the asymmetry is less likely to be due to natural geography or a state’s interest in protecting minorities or keeping cohesive jurisdictions together (which is accounted for by the simulations). In this way, their approach distinguishes between unintentional and intentional asymmetries in partisanship.

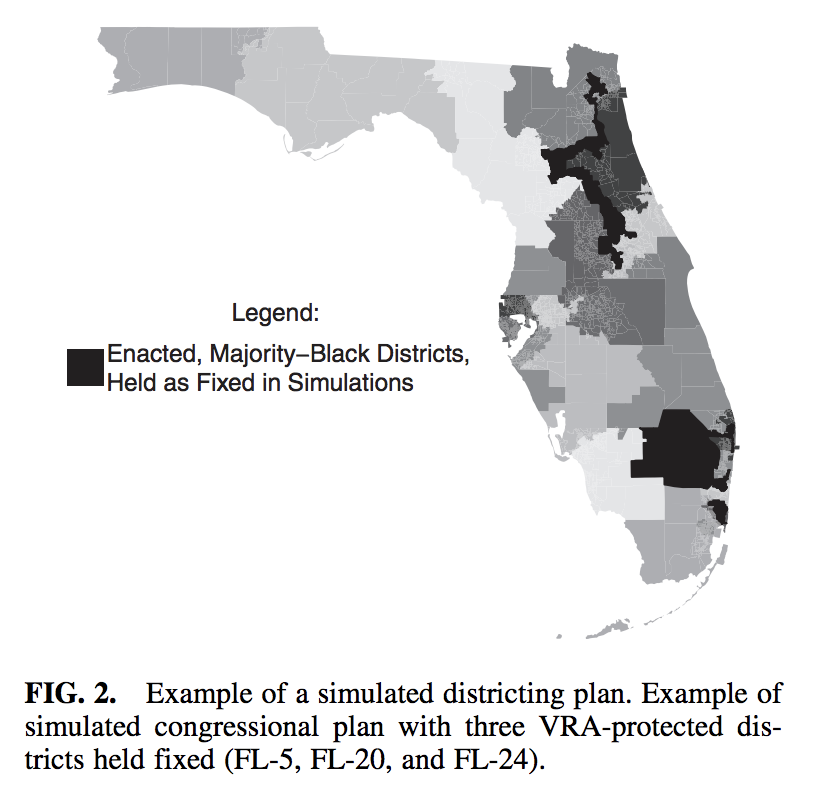

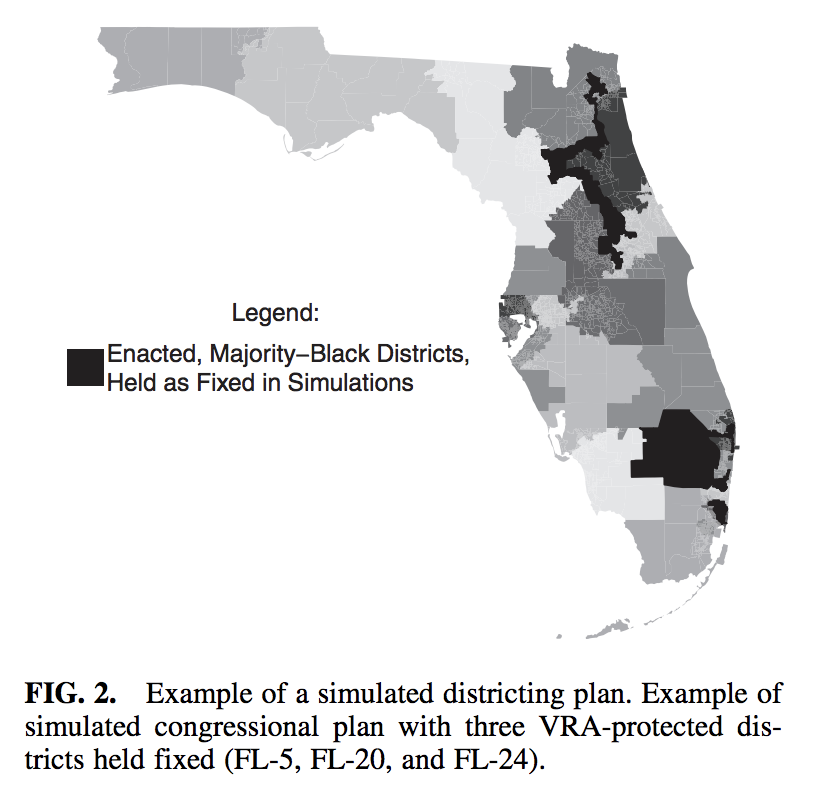

Using data from the Florida case, Chen and Rodden simulated the results of 24 districts in 1,000 simulated plans. They kept three African-American districts intact because of Voting Rights Act protections. They also kept 46 counties and 384 cities together, giving the benefit of the doubt to the legislature that compelling reasons exist to keep these entities within the same simulated district. The algorithm uses a nearest distance criterion to keep districts geographically contiguous and highly compact, and it iteratively reassigns precincts to different districts until equally populated districts are achieved. The figure below shows how this looks in one of the 1,000 valid plans.

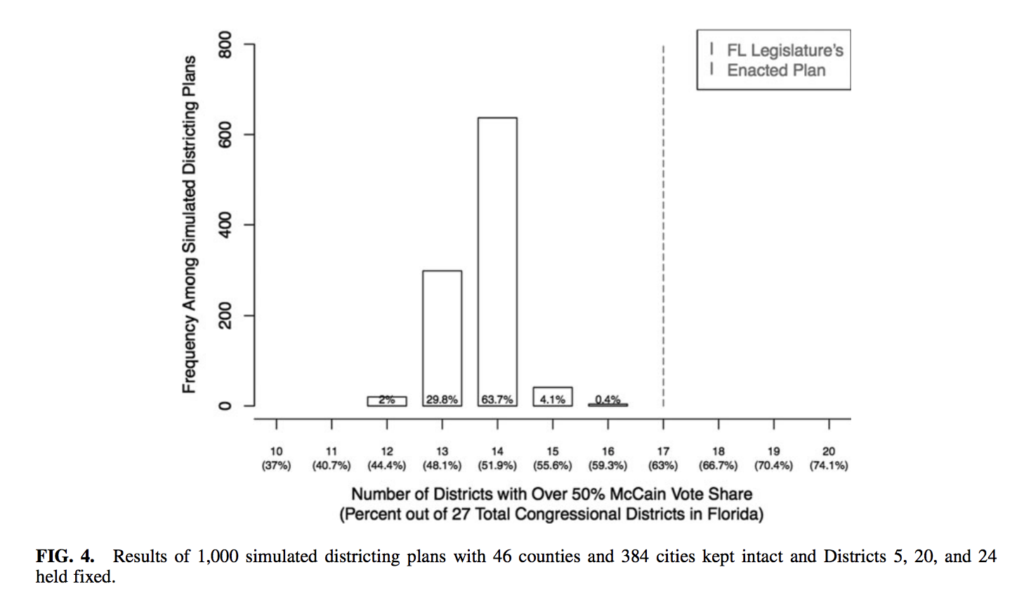

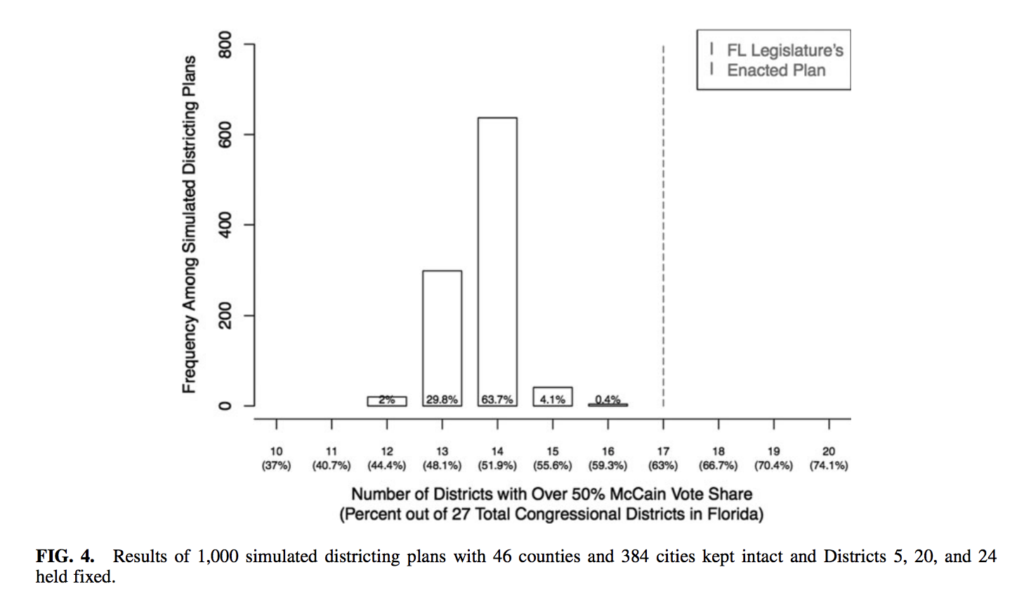

Next, to measure partisanship, Chen and Rodden needed both the most recent data possible and precinct-level election results, which they found in the 2008 presidential election results. For both the existing plan and the simulated plans, they aggregated from the precinct to the district and calculated the number of districts where McCain voters outnumbered Obama voters. The figure below shows the partisan distribution of all of the plans. A majority of the plans created 14 Republican seats, and less than half of one percent of the plans produced 16 Republican seats. However, none of the simulations produced the 17 seats that were in the Florida Legislature’s plan, showing that the pro-Republican bias in the Legislature’s plan is an extreme outlier relative to the simulations.

Because the simulations they created were a conservative test of redistricting (e.g., giving the benefit of the doubt to the Legislature by protecting three African-American districts), Chen and Rodden also tried the simulations by progressively dropping some of the districts they had previously kept intact. Results suggested the Legislature’s plan was even more atypical, as they had less pro-Republican bias than the simulations with the protected districts.

Chen and Rodden note that once a plaintiff can show that the partisanship of a redistricting plan is an extreme outlier, the burden of proof should shift to the state. Ultimately in Florida, eight districts were found invalid and, and in December 2015, new maps were approved by the court and put into use for the 2016 Election.