Mar 5, 2020 | Uncategorized

Post developed by Kelly Askew and Katherine Pearson

Maasai Remix, a documentary directed by the award-winning team of filmmaker Ron Mulvihill and anthropologist Kelly Askew, follows three Maasai individuals who confront challenges to their community by drawing strength from local traditions, modifying them when necessary, and melding them with new resources.

Maasai Remix, a documentary directed by the award-winning team of filmmaker Ron Mulvihill and anthropologist Kelly Askew, follows three Maasai individuals who confront challenges to their community by drawing strength from local traditions, modifying them when necessary, and melding them with new resources.

The three subjects of this documentary live in different settings. Adam Mwarabu advocates for Maasai pastoralists’ rights to land in international political spheres. Evalyne Leng’arwa pursues a college education in the U.S., having convinced her father to return 12 cows to a man contracted to marry her. Frank Kaipai, the village chairman, faces opposition as he promotes secondary school education and tries to save the village forest. Sharing a goal of Maasai self-determination in an ever-changing world, Adam, Evalyne, and Frank innovate while maintaining an abiding respect and love for their culture.

In a companion film produced by Kelly Askew entitled The Chairman and the Lions, the focus was on the many challenges faced by Parakuyo Maasai, including marauding lions, landgrabbers, illegal loggers, male youth out-migration and lack of education. By contrast, the message of Maasai Remix is one of hope and innovation, and of connected yet individual initiatives in addressing communal challenges. It champions the use of tradition as a mode of community development and as such offers a rebuttal to the widespread view that culture is always and only an obstacle to development initiatives. Quite the contrary, Adam, Evalyne and Frank illustrate through word and deed how traditions can be deployed as tools of empowerment. Thus, integrating their culture with modernist goals in a manner, not unlike the remixes of hip-hop DJs, Maasai Remix celebrates the achievements of these individuals and the lifeways of their community.

Dec 11, 2019 | Current Events, Policy, Profile, Race, Social Policy, Uncategorized

Shea Streeter

Post developed by Katherine Pearson

Shea Streeter began her graduate work in political science as a comparativist interested in state repression around the world. When the protest movement in Ferguson, Missouri exploded after the killing of Michael Brown, Streeter turned her attention to police violence and protest in the United States. As a President’s Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Michigan, she’s examining how race and gender shape the ways that people experience, perceive, and respond to incidents of violence.

“Racial animus is in the air we breathe,” Streeter says, “but when we look at police violence, we can get distracted by race and ignore other important factors.” Her dissertation included an experiment to examine how the race of victims of police violence determines whether the public sees the violence as just. Surprisingly, she finds that the race of the victims is less salient than expected. Instead, the social context strongly shaped the attitudes of the respondents. Those who were predisposed to consider societal and institutional forces were less likely to believe the victim deserved the outcome, compared to respondents who place sole responsibility on the individual.

Racial differences in rates of protest

Half of the people killed by police each year are white, and yet the rate of protest over white victims of police violence is very low. A dataset that Streeter is currently completing includes all publicly available information on police killings and any protests that happened in 2015-2016. For those two years, about a third of the police killings of African Americans led to some sort of protest, but when whites were killed by police, protests occurred only five percent of the time. “I argue that it’s the biggest racial gap related to policing,” Streeter says. “There are a lot of reasons we could point to why African Americans would be protesting. But why wouldn’t whites also be protesting when their community members are killed?”

When conducting field research in several different cities in the United States, Streeter asked community organizers about protests for white victims of police violence. The organizers told her that they reach out to the families of white victims, but those families often do not want to be involved with protests. Instead, many white family members express understanding and forgiveness toward the police. Streeter makes sense of these reactions by tying them to the psychological concept of a belief in a just world. The idea is that people get what they deserve and they deserve what they get. Streeter observes that even when people who hold this belief lose a member of their own family, their trust in the police remains unchanged. “If you have these beliefs, it can be like a double loss,” Streeter notes, which may explain why there are fewer protests for white victims of police violence.

The role of mentorship

Mentorship has played a large role in Streeter’s academic career. Christian Davenport became a mentor to her when she was a senior at Notre Dame. At that time, Streeter was thinking about her career but hadn’t considered pursuing research. While working as a research assistant for Davenport, he encouraged her to pursue graduate work in political science. Streeter cites this support as a key reason she decided to come to the University of Michigan. She also gives credit to David Laitin and Jeremy Weinstein at Stanford, who pushed her to study the United States when she was training as a comparativist. “I had confusion about what my identity as a scholar would be if I changed paths, but they put my fears to rest, so I give them a lot of credit for helping me pursue this research path,” Streeter says.

Looking forward

In addition to her ongoing research on police violence, Streeter is turning her attention to the ways interpersonal violence affects the way that people think and act politically. She sees connections between different types of violence, including mass shootings, domestic violence, and suicide. “We don’t often see these as political violence, but they affect how people operate in the world,” Streeter says. She’s especially interested in the ways violence affects people differently based on gender. Streeter’s work is innovative and varied, but united by a common theme, which she sums up as “How does violence affect our world, and what are the aggregate consequences of that? That’s the big picture.”

Nov 20, 2019 | Uncategorized

by Katherine Pearson

How do voters make sense of the information they hear about candidates in the news and through social media? This question was at the heart of a collaboration between researchers at the University of Michigan, Georgetown University, and Gallup to study political communication that took place during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Mike Traugott, Ceren Budak, Lisa O. Singh, and Jonathan Ladd presented findings from the study at the Michigan Institute for Data Science (MIDAS) Seminar on November 14, 2019. The panel discussion, moderated by Rayid Ghani, covered results that will be published in a new book, Words That Matter, in May 2020.

Rayid Ghani, Jonathan Lass, Lisa O. Singh, Ceren Budak, and Mike Traugott at the MIDAS symposium.

Genesis of the project

The project began when Gallup contacted Mike Traugott, a scholar of political communication who works in the area of attention to media using survey methods. In the four months leading up to the 2016 presidential election, Gallup conducted 500 interviews per day, asking respondents whether they had heard, read, or seen anything in the last few days about each of the two major-party candidates. In addition, the research team analyzed a sample of tweets from the public and from journalists. Finally, they compiled a database of news articles about the election, and also conducted an analysis of fake news.

Data visualizations were an important part of this work, said Traugott. As data was gathered and interpreted, the researchers created visualizations and analyses that were published on the Gallup website and in The Washington Post and other news outlets. Excellent graphics were essential to show complex data in an easily interpretable way.

Interdisciplinary strengths

Researching political communication using big data and data from multiple sources was an exciting challenge for the members of the team. When survey respondents are asked to recall what they’ve heard, read, or seen, there is the potential for error stemming from everything from memory problems to social desirability bias. Working with an interdisciplinary team was an opportunity to use new methods to analyze big data and mitigate such errors.

Closed-ended survey questions can be difficult to interpret; researchers sometimes try to find out what people actually mean by asking open-ended follow-ups. The surveys in this study only collected open-ended responses, allowing respondents to give more meaningful answers. With such a large sample of open-ended responses about what people remembered about the candidates, it was essential to find innovative ways to analyze the data.

Lisa Singh and Ceren Budak, both computer scientists, contributed expertise in computational social science and experience working with social media data. A variety of techniques were used in the analyses contained in the book: frequent word analysis, topic analysis, network analysis, sentiment analysis, and more. The open-ended text from the survey responses was so noisy and short that the algorithms were not enough to interpret the results. It took a team effort to interpret the data through a semi-automated process. The team at Gallup and the political scientists sorted words into topics and created synonym dictionaries to clean the data and remove inconsistencies. Developing these tools to be applied in domains where the text is not as rich and complete will be a focus of future work.

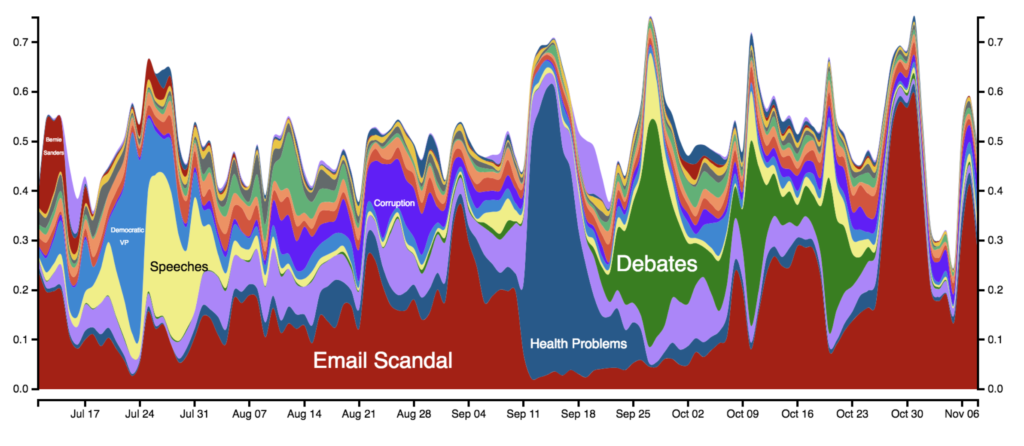

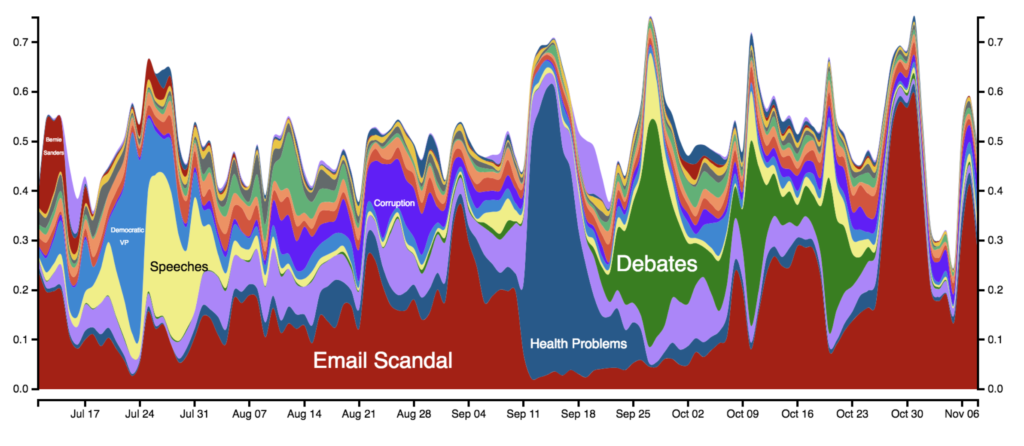

A long-lived narrative is worth more than many explosive stories

Ladd noted that by analyzing text data – tweets and open-ended survey responses – the research team found that people repeatedly remembered Hillary Clinton’s emails throughout the campaign. The fact that this one story dominated the narrative about Clinton seemed to have an effect on voters, and Ladd points out that Clinton echoed this finding in her book, What Happened, employing one of the project’s graphics in the text. On the other hand, people remembered many different news stories about Donald Trump over time. These stories appeared and disappeared quickly, and no one story made a big impression on respondents.

This figure highlights the changing topics that Americans remember about Clinton since July. The x-axis shows the date and the y-axis the fraction of responses that fall into a particular topic.

Another major finding of the study is that there were differences between the news that survey respondents recalled hearing and the text analysis of media articles, and both of those were different from what journalists were tweeting about. By analyzing streams of data from multiple sources, the researchers were able to conclude that journalists’ tweets and the text of newspaper articles did not favor either candidate.

Singh noted that Trump was masterful in keeping the issue of Clinton’s emails central to the campaign narrative. When the researchers analyzed new articles and tweets from journalists, email was not a dominant topic, as it was in the survey responses. She said that it was the Trump campaign that kept the narrative about the emails in the public’s awareness.

Connecting media coverage and voting behavior

Members of the research team who were not available to participate in the panel discussion contributed further analyses to the book. Stuart Soroka conducted a sentiment analysis of the open-ended responses, and Josh Pasek did work on story life and length of time an item was in the news. One limitation of this study was that Gallup did not collect any direct measure of voter preference, although they did collect favorability ratings of the candidates every day, which gave the researchers an indirect measure to work with. There was a lagged relationship between the net sentiment of Trump and Clinton in the news and the relative favorability of the two candidates.

We can’t know how fake news influenced votes, said Budak, who analyzed social media data in the 2016 election cycle. In a chapter on fake news in Words That Matter, she examined Clinton’s net favorability and found a strong relationship between fake news and her favorability rating. Specifically, Budak found that Clinton’s favorability would move first, and fake news responded to that. The creators of fake news were attuned to what was happening in the campaign and responded accordingly.

When Budak analyzed retained information data according to political leanings, she found that Republicans retained fake news coverage about Clinton, but not for Trump. The conversation about Trump changed a lot over time, while the narrative about Clinton stayed focused on her emails. According to Budak, “we can’t say fake news caused the outcome of the election, but it shaped the agenda.”

Jul 23, 2019 | Innovative Methodology, Policy, Profile, Race, Social Policy, Uncategorized

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo

Feelings of belonging are powerfully important. A sense of inclusion in a group or society can motivate new attitudes and actions. The idea of belonging, or attaining inclusion, is the centerpiece of Angela Ocampo’s research. Her dissertation exploring the effect of inclusion on political participation among Latinos will receive the American Political Science Association’s (APSA) Race and Ethnic Politics Section’s award for the best dissertation in the field at the Fall 2019 APSA meetings.

Dissertation and Book Project

Dr. Ocampo’s dissertation grounds the theory of belonging and political participation within the literature. This research, which she is expanding into a book, finds that feelings of belonging in American society strongly predict higher levels of political engagement among Latinos. This concept represents the intersection of political science and political psychology. Dr. Ocampo draws from psychology research that belonging is a human need; people need to feel that they are a part of a group in order to succeed and have positive individual outcomes, as well as group outcomes. She builds on these psychological concepts to develop this theory of social belonging in the national community, and how this influences the perception of relationship to the polity.

The book will explore the social inclusion of racial and ethnic minorities, and how that shapes the way they participate in politics. Dr. Ocampo argues that the idea of perceiving that you belong, and the extent to which others accept you, has an influence on your political engagement and opinion of policies. For the most part, Dr. Ocampo looks at Latinos in the US, but the framework is applicable to other racial and ethnic groups. She is also collecting data among Asian Americans, African Americans, and American Muslims to look at perceived belonging.

Methodological Expertise

Before she began this research, there were no measures to capture data on belonging in existing surveys. Dr. Ocampo validated new measures and tested and replicated them in the 2016 collaborative multiracial postelection survey.

While observational data is useful for finding correlations, it can’t identify causality. For this reason, experiments also inform Dr. Ocampo’s research. In one experiment, she randomly assigned people to a number of different conditions. Subjects assigned to the negative condition showed a significant decrease in their perceptions of belonging. However, among those assigned to the positive condition, there were no corresponding positive results. In both the observational data and experiments, Dr. Ocampo notes that experiences of discrimination are highly influential and highly determinant of feelings of belonging. That is, the more experiences of discrimination you’ve had in the past, the less likely you are to feel that you belong.

Doing qualitative research has taught Dr. Ocampo the importance of speaking with her research subjects. “It’s not until you get out and talk to people running for office and making things happen that you understand how politics works for everyday people. That’s why the qualitative data and survey work are really important,” she says. By leveraging both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, Dr. Ocampo is able to arrive at more robust conclusions.

A Sense of Belonging in the Academic Community

Starting in the Fall of 2020, Dr. Ocampo will be an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Faculty Associate of the Center for Political Studies. She says that the fact that her work is deeply personal to her is what keeps her engaged. As an immigrant herself, Dr. Ocampo says, “I’m doing this for my family. I’m in this for other young women and women of color, other first-generation scholars. When they see me give a class or a lecture, they know they can do it, too.”

Dr. Ocampo is known as a supportive member of her academic community. She says it’s an important part of her work: “The reason it’s important is that I wouldn’t be here if it wouldn’t have been for others who opened doors, were supportive, were willing to believe in me. They were willing to amplify my voice in spaces where I couldn’t be, or where I wasn’t, or where I didn’t even know they were there.” She notes that in order to improve the profession and make it a more diverse and welcoming place where scholars thrive, academics have to take it upon themselves to be inclusive.

Jun 27, 2019 | Uncategorized

Post developed by Yuri M. Zhukov, Christian Davenport, Nadiya Kostyuk, and Katherine Pearson.

How can scholars of political conflict and violence apply research in different settings? Too often, data that are collected and analyzed in one setting cannot inform us about situations in other regions. The problem is not a lack of data. Instead, researchers are unable to make comparisons because variables, definitions, and units of analysis are inconsistent between sources.

xSub, a new freely available resource, solves these problems by building the infrastructure to compare data on political conflicts and violence at a subnational level (i.e., states, cities, and villages).

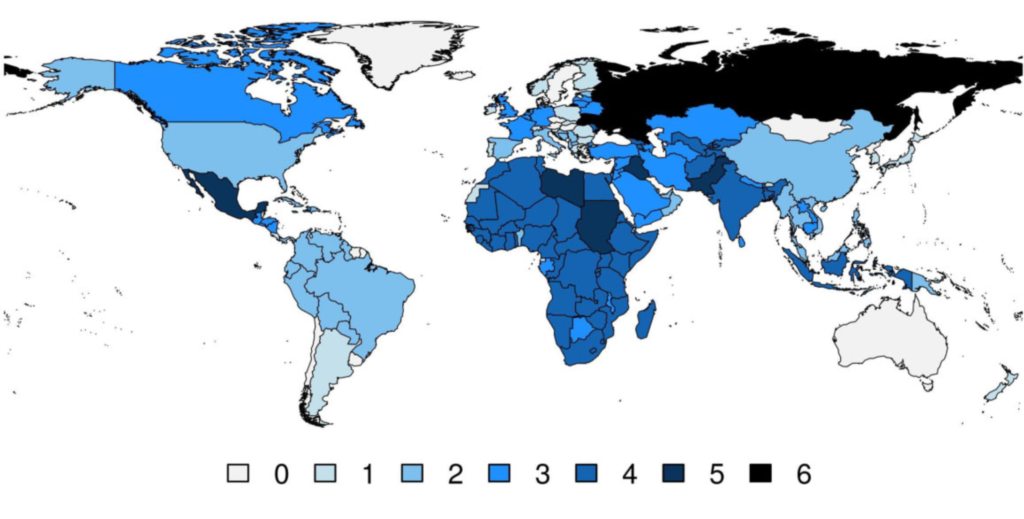

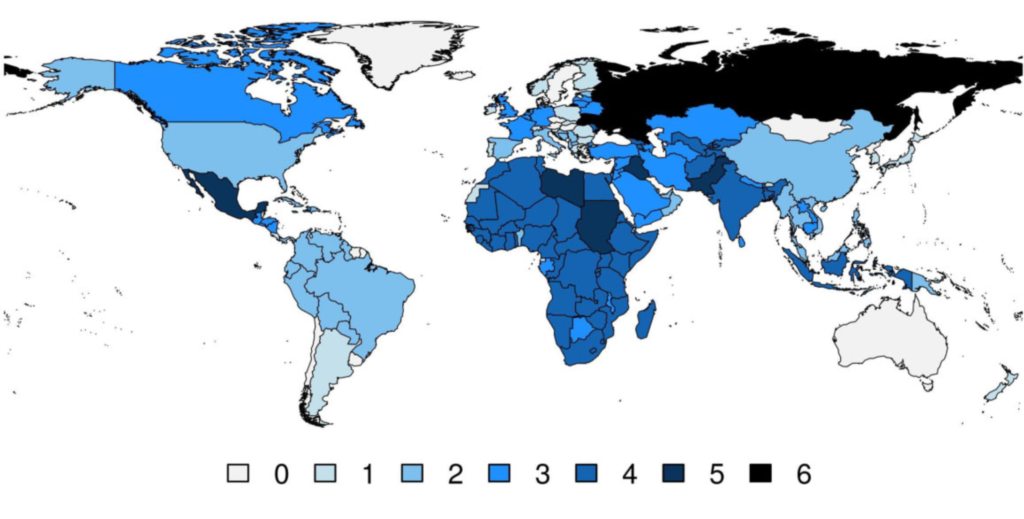

In a newly-published paper [1], Yuri M. Zhukov, Christian Davenport, and Nadiya Kostyuk introduce xSub, a database of databases that allows researchers to construct custom, analysis-ready datasets. xSub includes data on conflicts in 156 countries, from 21 sources. The project is also collecting data on countries with little or no publicly accessible information about what takes place within them. Additionally, scholars can contribute data they have collected for use by other researchers for future studies.

Why xSub?

Zhukov, Davenport, and Kostyuk describe five main problems with existing datasets:

- Most studies of political conflict aggregate data to the country level (i.e., the situation in Afghanistan or the United States writ large, rather than specific locations and contexts);

- Most micro-level studies focus on very few countries;

- Cross-dataset comparisons are rare;

- Operational definitions of variables (including event categories, actors, and spatial units) vary;

- There are no consistent units of analysis, which might otherwise enable direct comparisons.

To address these problems, xSub provides barrier-free access to data in an analysis-ready format, with consistent definitions, measures, and units. Without the effort to build this infrastructure, the field of study cannot move forward.

What’s in xSub?

xSub makes it easy to compare data across countries and sources because it organizes these data into consistent categories. Here’s what users will find:

- Data sources: 25,112 datasets on the location, dynamics, and intensity of conflict events, in 156 countries (1969–2017), from 21 data sources, with consistent categories and customizable spatiotemporal units.

Number of unique data sources per country

- Actors: xSub organizes data on those involved in conflicts into four categories: government (Side A), opposition (Side B), civilian (Side C), and unaffiliated (Side D).

- Actions: there are 4 general and 27 specific categories of actions, including any use of force, indirect force (e.g. shelling, air strikes, chemical weapons), direct force (e.g. firefights, arrests, assassinations), and protests, both violent and nonviolent.

- Covariates: In addition to conflict, xSub includes multiple variables frequently used in subnational research: e.g., local demographics, geography, ethnicity, and weather.

- Units of analysis: xSub provides event-level and spatial panel datasets. Researchers can choose the geographic units (e.g. countries, provinces, districts, PRIO-GRID cells, and electoral constituencies) and units of time (e.g. years, months, weeks, and days) to analyze. The units that a scholar chooses will affect the distribution of the data, allowing for a more precise description of findings.

How to access xSub

Anyone interested in analyzing xSub data is already able to access it because it is available in a user-friendly web interface and an R package. Removing barriers to access means that anyone from undergraduates to senior researchers will be able to work with these data, gauging whether or not patterns in one country apply to others in the same region or throughout the world.

The interactive web-based interface is available at cross-sub.org. Here scholars can select countries, data sources or units of analysis, preview the data, and download a zipped archive with the requested data and supporting documentation.

More advanced researchers can access the xSub R package at https://cran.r-project.org/package=xSub. This package provides additional functionality not supported by the website, including direct import of data into R and merging of datasets across countries.

By developing xSub, Zhukov, Davenport, and Kostyuk have created a public good that will advance a more meaningful understanding of political violence. With this new tool, researchers are now empowered to answer questions and share data in a way that was impossible until now. With numerous additions underway, the project looks to continue to advance the field into the future.

[1] Zhukov, Y. M., Davenport, C., & Kostyuk, N. (2019). Introducing xSub: A new portal for cross-national data on subnational violence. Journal of Peace Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319836697

Apr 25, 2019 | Current Events, Social Policy, Uncategorized

By Michael Rozansky. Original post for the Annenberg Public Policy Center.

One of the most heavily watched and debated fictional portrayals of suicide in recent years was the Netflix series “13 Reasons Why,” which raised outcries about potential contagion stemming from its portrayal of a female high-school student’s suicide.

Google searches about suicide spiked after the release of Season 1, physicians said that several children created lists of “13 reasons why” they wanted to kill themselves, and one hospital saw an increase in admissions of children who exhibited suicidal behavior. But two studies conducted after the series was released found some beneficial effects.

Given the series’ popularity and its potentially harmful effects, researchers at the University of Vienna, the University of Leuven, the University of Michigan, and the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) conducted a study to more fully understand the effects of the show through a survey of U.S. young adults, ages 18 to 29, before and after the May 2018 release of its second season.

In the study, published today in the journal Social Science & Medicine, researchers found that:

- Viewers who stopped watching the second season partway through reported greater risk for future suicide and less optimism about the future than those who watched the entire season or didn’t watch it at all;

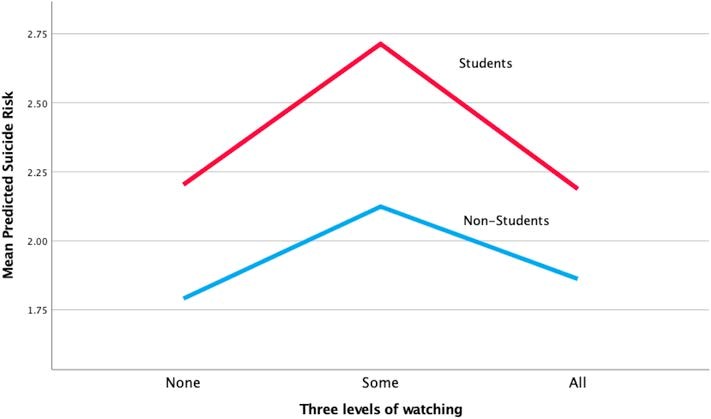

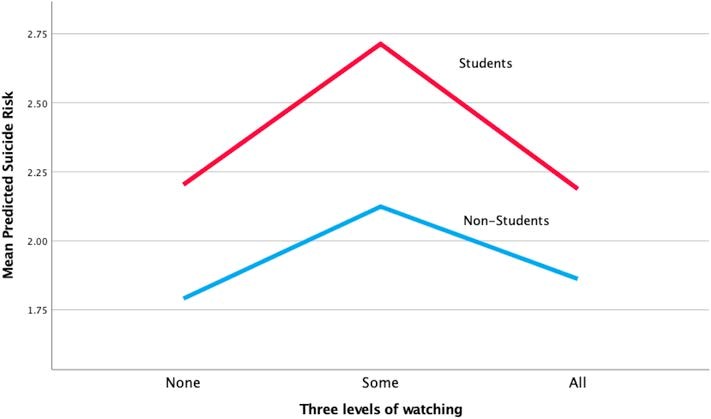

- Students – who were nearly 60 percent of the sample – were at an overall higher risk for suicide. Of the viewers who dropped out of watching the series midway, students were at a significantly higher suicide risk than non-students (see Figure 1);

- The show appeared to have a beneficial effect on students who saw the full second season: They were less likely to report recent self-harm and thoughts of ending their lives than comparable students who didn’t watch the series at all. And viewers in general were more likely to express interest in helping a suicidal person, especially compared with those who stopped watching;

- Netflix’s warning about the show’s potentially disturbing content that preceded Season 2 mainly appeared to increase viewing but did not appear to prevent vulnerable viewers from watching the season.

“Although there’s some good news about the effects of ‘13 Reasons Why,’ our findings confirm concerns about the show’s potential for adverse effects on vulnerable viewers,” said Dan Romer, APPC’s research director and the study’s senior author. “It would have been helpful had the producers done more to enable vulnerable viewers to watch the entire second season, which is when the show had its more beneficial effects.”

Fig. 1: Predicted suicide risk

Background on the study

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year-olds. Media portrayals of suicide have been shown to have helpful and harmful effects. Stories of suicide in news and fictional media can elicit suicide – especially when they explicitly show suicide methods – in a phenomenon called the Werther effect, after Goethe’s novel “The Sorrows of Young Werther.” By contrast, news stories about people who have overcome a suicidal crisis have had a positive impact, a more recently documented phenomenon that is known as the Papageno effect, after the character in Mozart’s opera “The Magic Flute.”

For this study the researchers surveyed 18- to 29-year-olds, who reported having access to Netflix, both shortly before the second season was launched and a month later. A total of 729 respondents completed both the initial internet survey and the follow-up, which used validated scales to measure future suicide risk, hopelessness, recent self-harm, and related outcomes. Women were over represented in this sample (82 percent), perhaps because “13 Reasons Why” involved a female protagonist.

An indicator of distress

“13 Reasons Why” seemed to be particularly upsetting for young people who were already at a higher risk of suicide and who empathized with the main character, 17-year-old Hannah, who is bullied and sexually assaulted before deciding to end her life. As the researchers wrote, “We hypothesized that watching only some of the series could be an indicator of distress that led those viewers to discontinue exposure to the upsetting content.” The results appeared to support that idea, in that those who watched only some of the second season showed elevated risk of future suicide, an outcome that was stronger for current students.

At the same time, students who watched the entire second season reported less self-harm after watching than those who did not watch at all. Thus the findings suggest that over the course of a month following the second season, the show exerted a beneficial effect on some students.

The researchers added: “One explanation for the beneficial finding is that those at higher risk who persisted to the end were able to empathize with the challenges faced by the main characters and to take away a life-affirming lesson applied to their own lives.” The second season may have conveyed this message with more effectiveness than the first season, which mainly focused on the harm that the suicide inflicted on the victim’s friends and family.

“Given that we know that the Werther effect is a real phenomenon with detrimental consequences, the public outcry about potential contagious effects as a response to the first season is justified,” said the study’s lead author, Florian Arendt of the University of Vienna, Austria. “However, the second season appeared to have more content that could engender a beneficial effect than the first season, and this may have helped those who watched it in its entirety to walk away with more beneficial outcomes.”

Viewers who watched the full second season were also more likely to be sympathetic to a hypothetical friend who appeared to be suicidal. Here again the findings suggest that the show may have succeeded in creating empathy for those in a suicidal crisis.

Evidence the show “can harm some… and may actually help others”

In an accompanying commentary on the study in Social Science & Medicine, Anna S. Mueller of the University of Chicago’s Department of Sociology and Comparative Human Development said the findings “offer the strongest evidence to date that 13RW can harm some youth and the results demonstrate that it may actually help others, which is rarely considered in the media and suicide literature.”

Mueller, who was not connected with the study, said, “It also has important implications for what scholars should do next.” That includes “unpacking how exposure to suicide – whether through media or a personal relationship – transforms an individual’s vulnerability to suicide.”

What should Netflix do?

Romer said, “Producers of shows such as ‘13 Reasons Why’ need to be aware of the potential effects of their shows, particularly on vulnerable audiences. One way to do this would be to make the series less aversive to people who are sensitive to a story about suicide, because they may not get to the parts of the story that have more uplifting effects.”

The researchers noted that the study had limitations, including the one-month time frame for the observed effects. Also, it did not assess respondents’ experiences surrounding sexual assault, an important element in the series in both seasons, which could have influenced reactions.

Romer and Arendt’s co-authors are Patrick E. Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Health and Risk Communication Institute at the Annenberg Public Policy Center; Sebastian Scherr, of the School for Mass Communication Research, University of Leuven, Belgium; and Josh Pasek, of the Department of Communication Studies and Center for Political Studies, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

The study “Investigating harmful and helpful effects of watching season 2 of 13 Reasons Why: Results of a two-wave U.S. panel survey,” is published in Social Science & Medicine.

Maasai Remix, a documentary directed by the award-winning team of filmmaker Ron Mulvihill and anthropologist Kelly Askew, follows three Maasai individuals who confront challenges to their community by drawing strength from local traditions, modifying them when necessary, and melding them with new resources.

Maasai Remix, a documentary directed by the award-winning team of filmmaker Ron Mulvihill and anthropologist Kelly Askew, follows three Maasai individuals who confront challenges to their community by drawing strength from local traditions, modifying them when necessary, and melding them with new resources.

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo