May 14, 2024 | ANES, Elections, National

A new book by leading scholars of partisanship explores the recent consequences of political hostility, and how it does and doesn’t affect democratic functioning

Is partisan hostility damaging American democracy?

The short answer is yes: Political animosity, which scholars recognize as the defining feature of American politics this century, can degrade democratic functioning. But the question begs for a long answer: To see and face the implications of partisan hostility, we need a nuanced understanding of its effects and its boundaries.

A forthcoming book by some of the foremost scholars of polarization amasses empirical evidence of the consequences of political hostility in recent years, and offers a theory of when it affects political beliefs and behaviors.

Partisan Hostility and American Democracy: Explaining Political Divisions and When They Matter (University of Chicago Press: 2024) will be released June 12 from authors James N. Druckman, Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Levendusky, and John Barry Ryan.

Study after study has shown a striking rise in negative feelings Americans hold toward the opposing party– a concept scholars call affective polarization. Roughly 8 in 10 partisans report these negative feelings, according to Pew Research Center, and the majority use pejorative words– such as “hypocritical,” “closed-minded,” and “immoral” to describe their counterparts. While partisans have maintained stable attitudes toward their own party over time, their “ratings” of the other party have plummeted since 1980 and notably in the last decade. The authors cite New York Times columnist David Brooks’s taut summation– in the age of affective polarization, “we didn’t disagree more– we just hated each other more.”

“We find that partisanship does shape political beliefs and behaviors, but its effects are conditional, not constant,” said co-author Yanna Krupnikov, an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research and a professor in the Department of Communication and Media. “It seems most likely to guide beliefs on issues that don’t have direct personal consequences, and it’s most powerful when parties send strong, clear cues on an issue.”

The authors test that framework using panel survey data from a 21-month period spanning 2019, 2020, and 2021– three tumultuous years that occasioned the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine distribution; the murder of George Floyd and subsequently the largest protest movement in US history; the 2020 election and January 6 insurrection; two impeachments, and a shift in the congressional majority.

The best data for measuring animosity over time, according to the authors, is the “feeling thermometer” in the American National Election Studies (ANES) survey, where respondents rate their feelings toward a party or issue on a 101-point scale, in which “50 degrees” is the neutral fulcrum between “warmer” or “colder” feelings. The authors use that measure in their own data along with additional measures: trust questions, trait ratings– where respondents evaluate how well positive and negative traits describe each party– and “social distance measures,” where respondents rank their comfort level in situations like having their child marry someone from the other party.

They find the effects of political hostility are most concentrated in individuals with comparatively high animosity, who are a distinctive group in America– with particularly strong political identities and high levels of political engagement. These “high animus” partisans are more likely to take and act on party cues about where they “should” stand, and more likely to reject the possibility of their own party compromising.

We can observe that animosity can fuel polarization on issues that might otherwise be informed by independent deliberation. In 1997, for example, Democrats and Republicans were equally likely to believe in climate change science; today, there’s a pronounced divergence that can only be explained by parties staking a claim on the issue, Krupnikov said.

The authors focus particularly on the case of politicization that drove the gap between Democrats and Republicans’ behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Political hostility is more likely to shape partisan evaluations of party leaders, they report, but the case of Dr. Anthony Fauci demonstrates how party cues can politicize specific targets. The authors also found the effects of COVID’s politicization on behaviors like vaccine or mask resistance diminished when actors confronted the personal stakes of the illness. To further understand these party signal dynamics and when they matter, the authors investigated the effect of animosity on policy positions in cases where issues are politicized by both parties, one party, and neither party.

“The advantage of our theory is its recognition that partisan divides are not inevitable and on many issues most people agree,” said John Barry Ryan, also an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies. “Overall, we see that animosity shapes decision-making by heightening the effects of party cues.”

The authors argue that while partisan hostility has degraded US politics—for example, politicizing previously non-political issues and undermining compromise—it is not in itself an existential threat. Political hostility has little effect on popular beliefs in fundamental norms, and it’s unlikely to directly lead to democratic breakdown or collapse, they say. They also find that overall, partisans do not strongly support undemocratic practices.

Yet there is considerable cause for concern that partisan hostility may erode democracy over time. Political hostility can result in blind loyalty and decision-making based purely on team mindset– with worrying implications– and animosity can spiral because it has self-perpetuating effects.

“We find that animosity has clear, predictable effects on prioritizing party over other considerations, especially for issues that lack clear and immediate consequences to a person,” Ryan said. “It affects policy positions that make democratic functioning difficult– like our willingness to compromise, or our judgments of party leaders, and how we respond to the pandemic.”

“Political elites can politicize issues and can potentially seize on division in hopes of gaining support,” said Krupnikov. “There is often a focus on voter division, but the future of American democracy depends often on how politicians– more than ordinary voters– behave.”

This post was written by Tevah Platt, communications specialist for the Center for Political Studies.

May 3, 2024 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International, National, Race

The national movement for divestment reflects the prevalence of prosocial politics.

by Eugenia Quintanilla

Activism on university campuses against U.S. investments in Israel has skyrocketed in the past several weeks. As of May 2, over 90 college campuses had Gaza solidarity encampments demanding university divestment from companies supporting Israel. Despite the historical precedence of campus activism on foreign policy matters (see opposition to the Vietnam war, South African apartheid, and the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq), there is public confusion about the popularity, depth, nature, and size of the university divestment movement. Onlookers blame the prevalence of pro-Palestinian activism on everything from limited syllabi at top universities, peer pressure effects, and even college students not having enough sex.

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting provocative slogans. Beyond tents and sleeping areas, many encampments feature Liberation Libraries, communal art-making, and worship spaces for Jewish and Muslim participants. At the University of Michigan, students from the TAHRIR coalition have organized daily programming including teach-ins, external speaker events, documentary screenings, and broader community education initiatives.

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting provocative slogans. Beyond tents and sleeping areas, many encampments feature Liberation Libraries, communal art-making, and worship spaces for Jewish and Muslim participants. At the University of Michigan, students from the TAHRIR coalition have organized daily programming including teach-ins, external speaker events, documentary screenings, and broader community education initiatives.

Student protestors and organizations have put forth specific demands and on some campuses, including Rutgers, the University of Minnesota, Brown University and Northwestern University, have reached agreements after negotiating tangible wins for the protesters related to divestment and protection of civil liberties. All of this work is happening on the heels of final exams, and commencement season, a time when college students should be the busiest. Yet activists at Emory, Columbia, UT Austin, New York University and other universities have faced brutal actions from police, violent anti-protestor attacks, more than 2,000 arrests, suspensions, and demands by political elites to call in the National Guard.

Starting and maintaining encampments is costly activism, requiring time, resources, and a willingness to endure bodily harm and legal repercussions. All of these costs should in principle reduce the likelihood of activism. But activists remain steadfast to their demands and actions, despite what we may expect. How can we better understand this wave of committed activism for Palestine?

Many Americans, I argue, are driven to political action by what can be called their prosocial politics, or their disposition to help groups in need. In what follows, I show the prevalence of prosocial politics as a driver of participation and how partisanship conditions the types of groups that Americans consider “in need.”

The Politics of Helping Others

Studying what mobilizes citizens to participate in politics is a foundational question to social scientists. Traditionally, this research analyzes citizens at the level of the individual. According to the “economic model,” individuals are essentially self-interested actors, and how they understand the costs and benefits of action determines whether they will participate. In the civic voluntarism model, an individual’s level of education, money, and time also make participation more likely.

However, more recent research shows the importance of group participation norms in determining likelihood of participation. Individuals who hold a norm of helping those in need are more likely to participate in higher-cost political participation. Psychology research on prosociality echoes the importance of helping as a cultural value, and an innate human behavior. If helping others is so important to human societies, how can we incorporate the desire to help into our models of political participation?

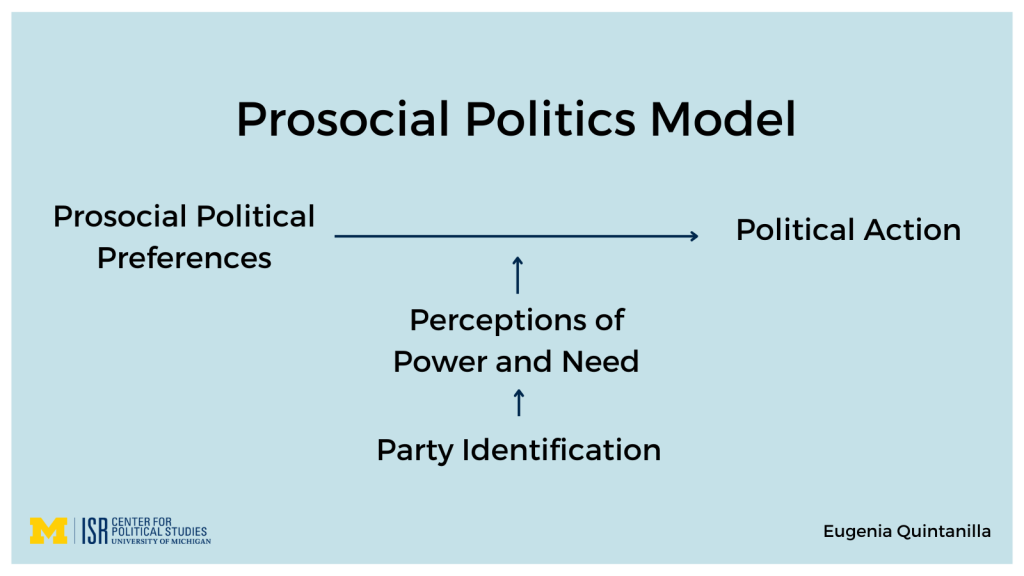

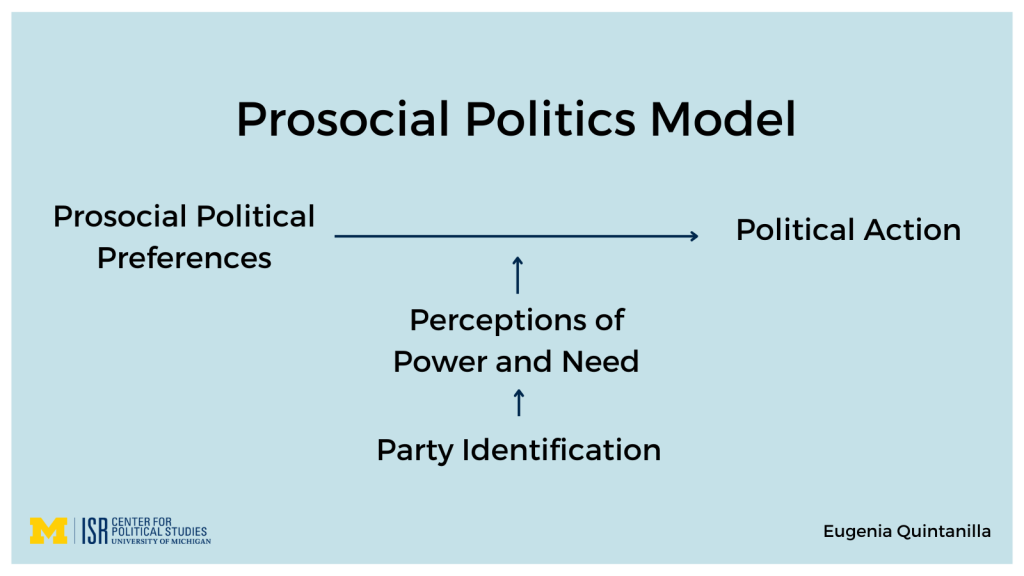

To answer this question, I offer a new theory called the “prosocial politics model.” In this model, citizens’ participation in politics is driven by how much they see helping others as a political value. The influence of this value is particularly strengthened by clarity around which groups are in need, and which groups are in power. As such, in the prosocial politics model, when citizens encounter a political situation they make automatic appraisals about three things:

- Whether helping others through politics matters to them

- Whether the group in question needs help, and

- Whether to take political action to help a group.

To establish evidence of the model in action, I created a measurement of prosocial political preferences in the form of six survey questions. I asked about civic prosocial norms and how helping is tied to politics in questions like, “In elections, how important do you think it is to vote in order to help others?” and “How much do you think politicians should focus on helping groups who are usually ignored?”

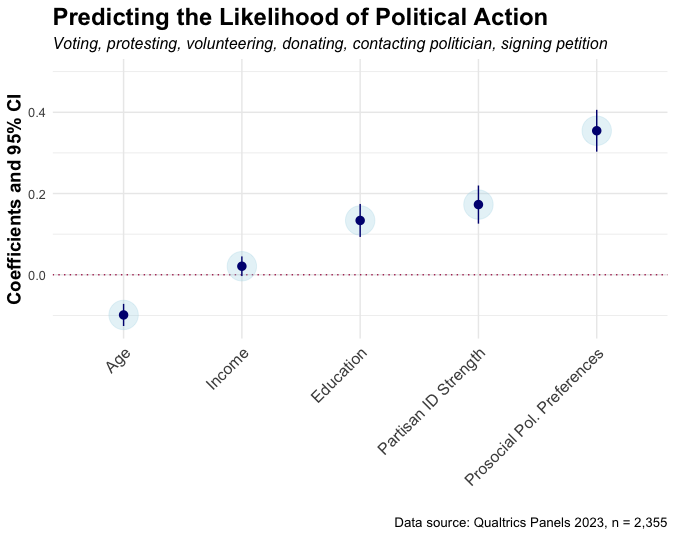

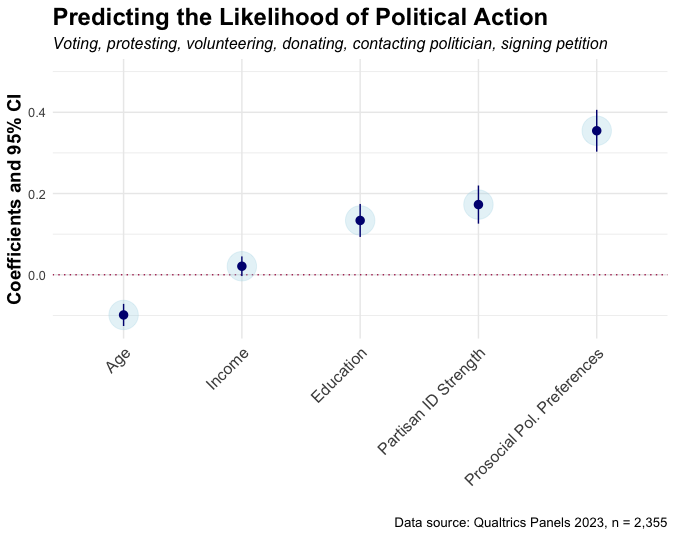

I fielded the prosocial political preferences questions in three separate national surveys of Americans, totaling 4,555 interviews. Across these surveys, I find that Americans on average have moderate to high scores on the scale (0.6 out of a 0-1). Additionally, I find that these political preferences are distinct from existing similar measures, such as group empathy, humanitarianism and egalitarianism, and generalized beliefs about helping others. Using a regression analysis, I find that prosocial political preferences outpace other common predictors, such as an individual’s age, their education, and their level of partisan identity strength.

Palestinians as a Group in Need

Another element of the prosocial politics model is social perception. Americans should be more responsive to a specific group, such as Palestinians, if they perceive that group to be in need– also known as the normative altruism model. Perceptions about need are not created in a vacuum. People rely on social groups to learn norms of helping obligation: the type of groups who should receive help, what the helping should look like, and the social stakes of helping. Public policy, such as welfare, also influences how we perceive the power and deservingness of groups.

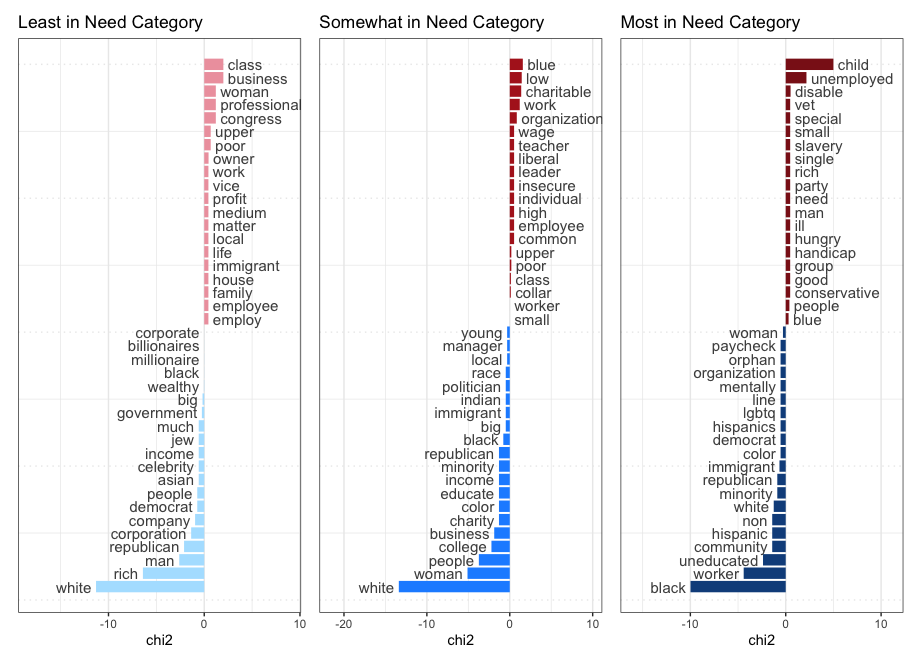

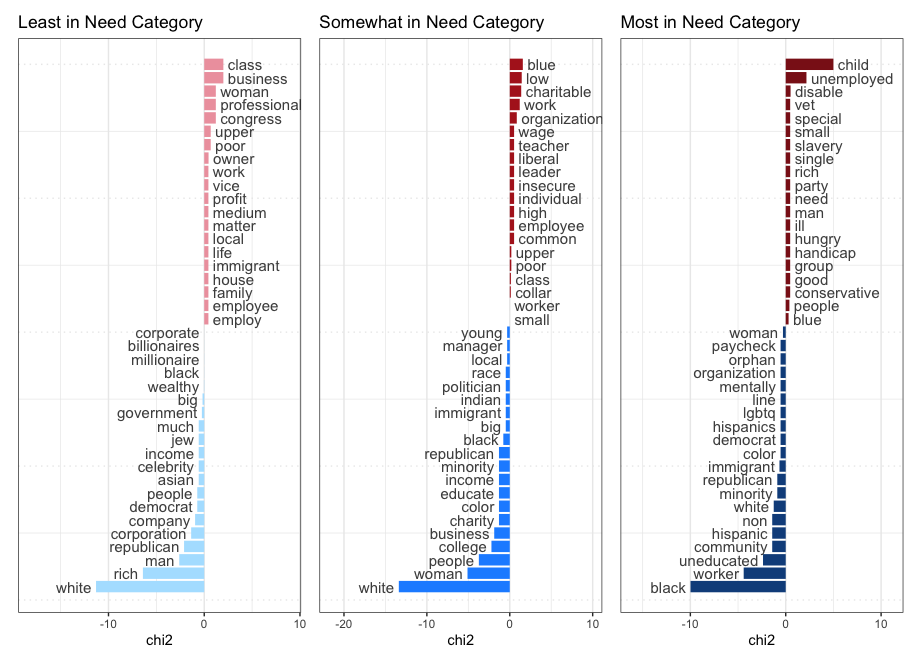

In the United States, political parties heavily shape and are shaped by the social identities of their members. As a result, I expect that partisanship modifies how Americans come to perceive which groups are in need, and which groups are not. To test this part of my theory, I piloted another novel measure called the “Circles of Power and Need,” or CPN for short. The CPN measure solicits a total of 12 text answers from each survey participant, six in Power and six in Need. With a team of undergraduates, I created a coding scheme to capture the breadth and nuance in how Americans describe stratification. We used 23 characteristic categories, and assigned binary values to organize text answers from respondents.

Through this analysis, we find that Americans use multiple dimensions to discuss Power and Need. Three characteristics are the most salient across the CPN measure: Class, Race and Ethnicity, and Institutions. Americans think about power in terms of institutions, parties and ideology groups, corporations, and class. When Americans think about need, they think in terms of class, employment status and racial/ethnic groups.

How Does Partisanship Shape Perceptions?

Democrats are overwhelmingly more likely to discuss groups in need in terms of race, ethnicity, and immigration status, while Republicans more frequently associate need with children, the disabled, and veterans. Republicans and Democrats both associate power and need with class, but Democrats reference ethnoracial and minority groups, such as Black people, White people, Hispanics, immigrants, and LGBTQ+.

The Political Consequences of Prosocial Politics

Images of Palestinian civilians killed as a result of Israeli military aggression have sparked protest, voting campaigns, and political activism. As of early May, 34,000 Palestinians have been killed by Israel’s military campaign in the past six months, including 17,000 children. Millions in Palestine are at risk of starvation as a result of alleged war crimes. Several legal experts refer to Israel’s actions as a genocide, increasing global urgency about assisting civilians at risk.

Public disagreements about the justification of Israel’s actions may not change the mobilizing effect of a steady stream of images of civilians dying, especially groups that are publicly considered more in need. Children, women, healthcare workers, foreign aid workers, educators, emergency responders, and journalists are all categories of people that are usually seen by the public as more deserving of help than other categories of people (e.g., soldiers, elected officials).

Americans protesting for the plight of Palestinians connect their cause to global justice problems like climate change, violence against indigenous populations, racism and policing. The breadth of these causes likely influences prosocial norms for Palestine, especially among youth who may have participated in the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in their adolescence.

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have higher disapproval rates for Biden’s handling of the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza in compared to their older copartisans (81% among 18-34 year olds, compared to 53% among all Democrats). In my dissertation, I also investigate how the absence of prosocial political preferences makes a difference in mobilization among individuals with different political attitudes, or issue positions. Additionally, I qualitatively study the prevalence of helping narratives in how Americans describe their own protest participation in 2020-2021.

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have higher disapproval rates for Biden’s handling of the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza in compared to their older copartisans (81% among 18-34 year olds, compared to 53% among all Democrats). In my dissertation, I also investigate how the absence of prosocial political preferences makes a difference in mobilization among individuals with different political attitudes, or issue positions. Additionally, I qualitatively study the prevalence of helping narratives in how Americans describe their own protest participation in 2020-2021.

Student activists likely have consolidated clear ideas about Palestinians as a group in need of help, and feel morally compelled to assist them in any way they can. According to recent polling from Gall Sigler and Daniel Hopkins, younger Americans express greater sympathy for Palestinians than older Americans. This is one of many political generational divides.

For college students, demanding financial divestment from companies sustaining military action is a tactic with historical precedence. Young student activists are not alone in this conviction. Understanding solidarity activism through the lens of prosocial politics clarifies the puzzle of why so many Americans are overcoming the costs of engaging in political action– especially since protest can be an effective means of recourse for disadvantaged groups to enact political change.

Pro-Palestine activism around the world has brought the suffering of Gazans to the attention of mainstream media, setting an agenda for the upcoming presidential election. Even if campus encampments are dispersed by police, counter-protestors, or administrators, U.S. military support for Israel will likely be a salient issue for many young Americans. Future research should consider how helping others as a political value challenges common understandings of what drives political participation.

Key Takeaways:

- The prosocial politics model offers a new way to understand why people decide to engage in political action.

- Prosocial political preferences, or the extent to which people see helping others as a political value, is a powerful predictor of political action.

- Exploring the nuance in how people conceptualize others in need can clarify situations where people may or may not be driven to action.

- Partisan cues and social norms affect whom we see as people in need. Although class signifies need across parties, Democrats bring up race and ethnicity more than Republicans, who typically mention age groups, such as children or the elderly.

- Through the lens of prosocial politics, we can understand the recent wave of committed activism as motivated by a desire to help Palestinians suffering in Gaza. U.S. military aid to Israel will be a salient issue for Americans in the 2024 presidential election.

Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.

Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.

Tevah Platt, communications specialist for the Center for Political Studies, contributed to the development of this post. Photos from William Lopez and Tevah Platt.

Jan 23, 2024 | Economics, National, Policy, Race

Information about the wealth gap between Blacks and whites increases Americans’ awareness of disparity, but does little to increase their support for affirmative action, reparations

Since the “racial reckoning” of 2020, Americans have become increasingly aware of the barriers Black people face to accessing economic opportunities and achieving intergenerational mobility.

But despite widespread knowledge that racial inequality exists, even among liberal, white Americans, the public is radically uninformed about the depths of one of the most profound racial disparities: the racial wealth gap.

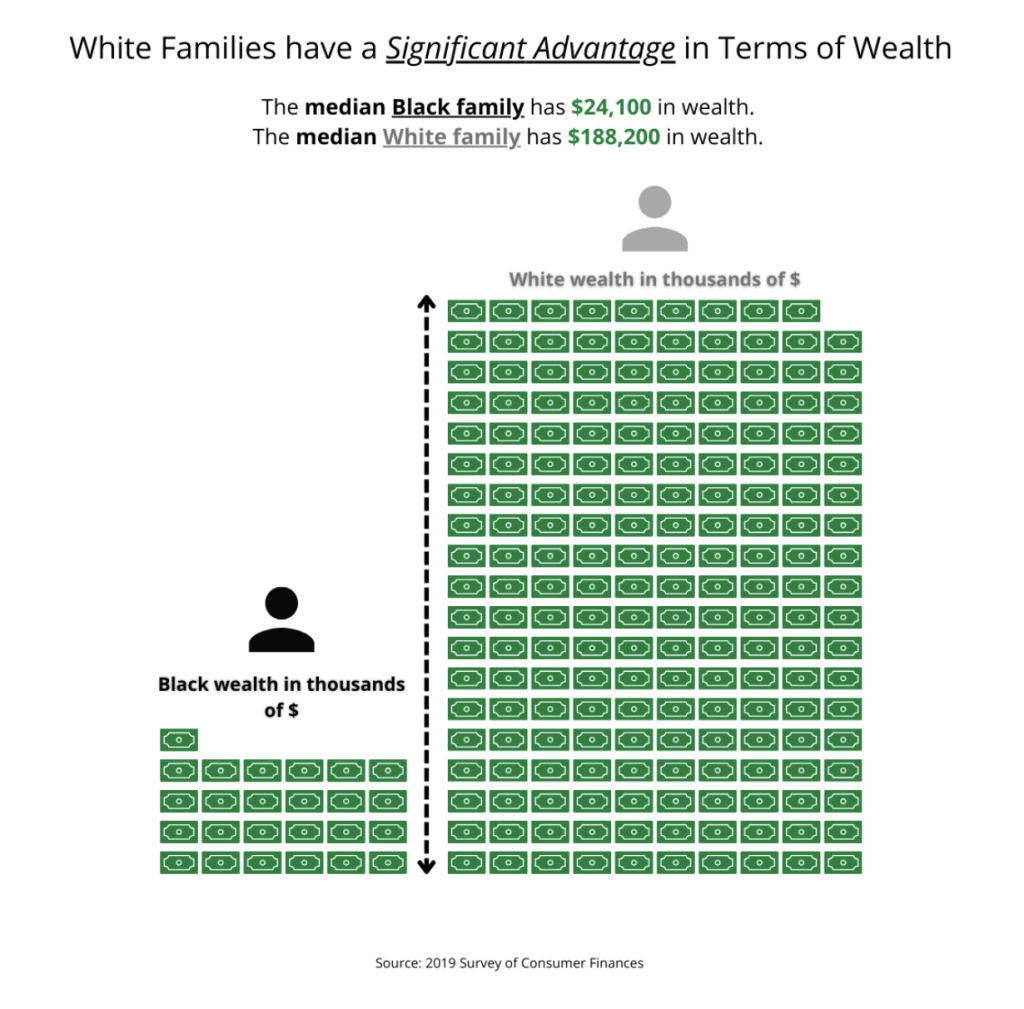

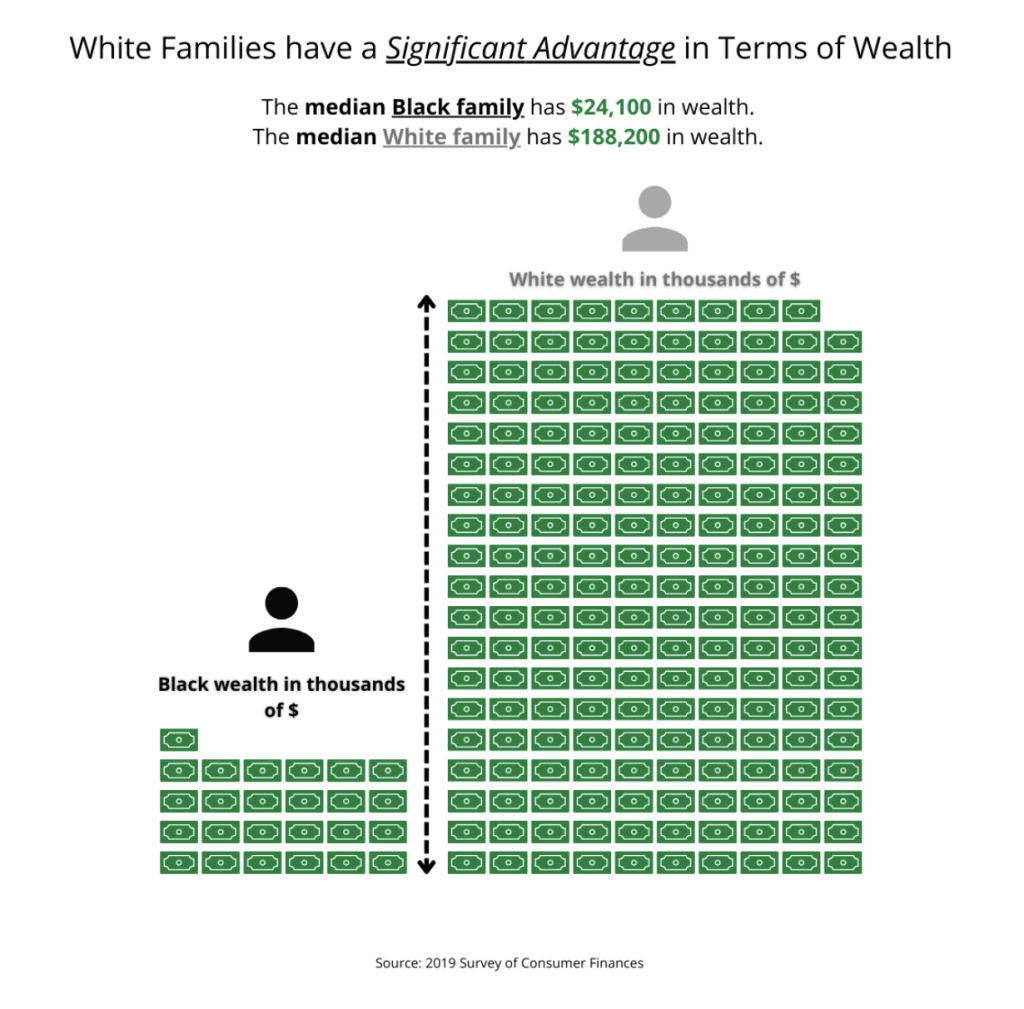

According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, which collects nationally representative data on American households, the median white family has about 8 times more wealth (that is, total assets minus total debts) than the median Black family. And, despite popular perceptions of education as the vehicle for eliminating racial disparities, education does little to diminish the gap between Blacks and whites. The median white family where the household head did not finish high school has virtually the same wealth as the median Black family where the household head earned a bachelor’s degree. In other words, a Black American has to graduate from college to access the same level of wealth as a white high school dropout.

If you find these numbers startling and even difficult to believe, you are not alone.

Since 2020, my research team, which includes Vincent Hutchings, Kamri Hudgins, and Sydney Carr, has been learning what happens when we correct misperceptions of the racial wealth gap. Does informing people about the size of the racial wealth gap influence opinions about policies to address the gap? How does the public react to information about the racial wealth gap?

Using a novel survey experiment fielded on three nationally diverse samples, we found that exposing both Black and white Americans to information about the size of the racial wealth gap increases their awareness of this disparity– but exposure to this information does little to increase their support for race-targeted social and economic policies like affirmative action and reparations.

For example, among white participants, exposure to our racial wealth gap information treatment increased awareness of the size and severity of the racial wealth gap by, on average, 7 to 18% across the two studies. However, exposure to the same information did not significantly increase support for race-targeted policy changes to reduce the racial wealth gap among white or Black participants.

In contrast, our treatments did increase support for race-neutral equity policies like baby bonds, a program that would fund a trust for every newborn child to establish a baseline level of wealth for all Americans. When informed that Black college graduates have the same level of wealth as white high school dropouts, both liberal and conservative white Americans’ support for baby bonds increased significantly. For conservatives, support increased by 12% moving from a baseline of .41 (indicating weak opposition) to .53 (indicating weak support). For liberals, support increased by 11% moving from .71 (strong support) to .82 (very strong support).

But economists argue that race-neutral programs like baby bonds or canceling student loan debt would not be nearly enough to close the racial wealth gap. For example, Duke University economist William Darity, Jr. proposes that only a comprehensive reparations program requiring “the full resources of the federal government” to redistribute wealth to Black Americans would be sufficient for closing the gap.

Those who believe legislative action on reparations is urgently needed will find the political momentum behind it at the federal level to be insufficient. President Joe Biden made the most progress on this issue of any president in history when he proposed a commission to study whether or not reparations should be paid to Black descendants of the enslaved. But the bill has effectively died in committee and there have been no votes on the House floor regarding the commission or any other reparations policies. While several states and localities have made more progress toward providing reparations to Black residents and, in some instances, (like Evanston, Illinois) have even begun issuing payments, these programs will not resolve the Black wealth crisis nationwide.

As this project develops, we hope to probe public opinion on other racial disparities, including the racial gap in rates of maternal mortality, and increase scholarly and public understanding of what it takes to move the public towards action on racial inequality.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

Zoe Walker is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Ford Foundation Predoctoral Fellow. Her dissertation research, supported by the Russell Sage Foundation, considers how beliefs about economic opportunity influence perceptions of racial inequality and support for racially redistributive policies among Black Americans.

Sydney Carr, Kamri Hudgins, and Zoe Walker are all Next Generation scholars of the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research and were consecutive recipients of the Hanes Walton, Jr. Endowment for Graduate Study in Racial and Ethnic Politics at the Center for Political Studies.

Hanes Walton, Jr. of the Center for Political Studies transformed the study of Black politics and helped establish it as a subfield of political science. The 2024 Hanes Walton Jr. Lecture at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research will be presented by Christian Davenport on Feb. 1.

Jan 4, 2024 | expert analysis, National, Race

After the murders of George Floyd and Breanna Taylor by the police in 2020, the United States witnessed what was arguably the largest protest movement in that nation’s history. Millions of Americans marched in protest of racist police violence and in pursuit of systemic solutions to racial inequality. Scholars have rightfully documented this moment in history, analyzing the different conversations and opinions about Black Lives Matter, racial minorities, and racialized policies. For example, some have analyzed Members of Congress’s communications to their constituents, news framing of the Black Lives Matter protests, and antiracism in sports, teaching curricula, and social media posting. Notably absent from this important set of research, though, is an understanding of how these conversations played out in what are arguably the most central institutions to the everyday lives of millions of Americans: churches.

The stakes are high for understanding the content of religious services. While the pandemic caused a decline in religious attendance, still about 40% of the American population attends a religious service at least once a month or more. The number of Americans who listen to a weekly message from a religious leader far outnumbers the fraction of Americans who watch the State of the Union, presidential debates, or the presidential inauguration. It is even more than the portion of Americans who say they follow the news “all or most of the time.” Moreover, researchers have found that both religious elites and attendance at religious services can influence a number of political attitudes and behaviors, such as electoral participation, ideology, and views towards issues such as poverty and immigration.

It matters how discussions about racism play out in religious spaces. These conversations both shape and represent how many Americans understand the origins of racism and solutions for racial inequality. In the case of the United States, many of the religious spaces where these conversations take place are Christian churches. Churches are a fruitful venue for understanding political discussion among the American public because religious services could be viewed as communication among individuals who share a common religious identity and—due to racial and political segregation among U.S. Christians—likely agree on a number of political issues.

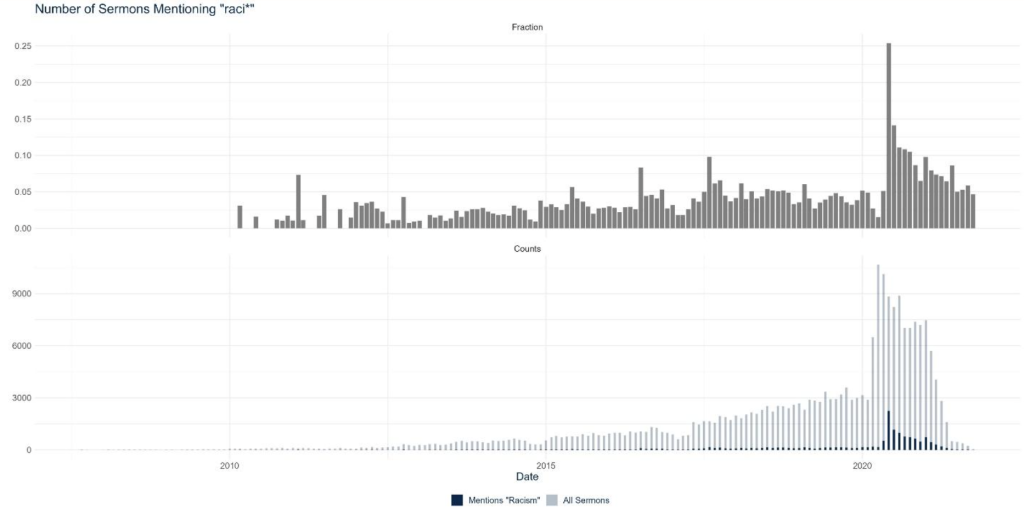

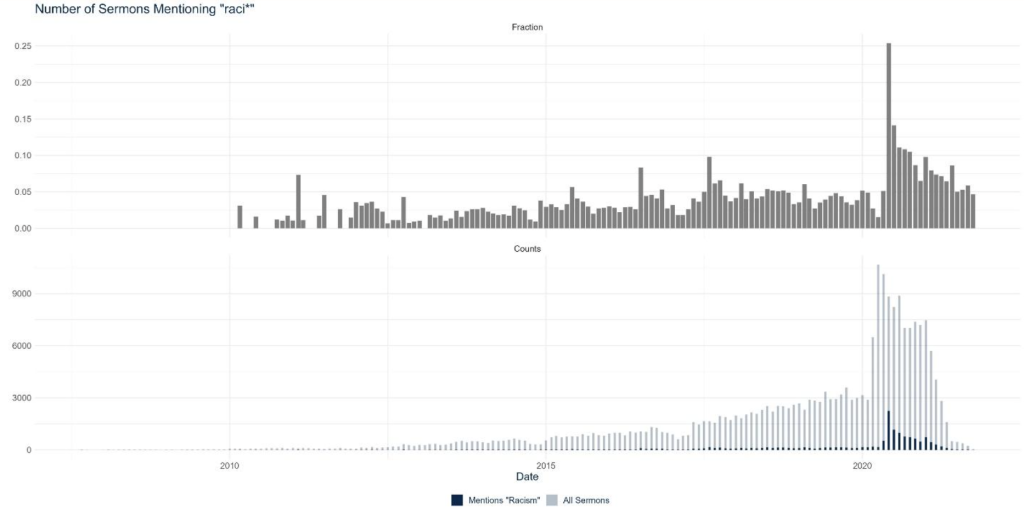

In my doctoral work in Political Science at the University of Michigan, I have analyzed sermons delivered in historically- and majority-white U.S. Christian congregations. I find that sermons infrequently mention racism: roughly 8% of sermons in my sample mention the words “racism,” “racist,” or “racial.” I also find only small distinctions across denominations. When clergy talk about racism, it is more frequently the case that racism and its perceived solutions are understood in individualistic rather than systemic terms. However, a few sermons do discuss racism as a more systemic issue, and call for the pursuit of racial equality.

In order to examine the contours of political discussion in religious spaces, I collected a dataset of transcripts of over 260,000 videos posted on YouTube by about 1,500 U.S. Christian congregations. Many congregations—especially in response to the pandemic—post recordings of their services online. These congregations are diverse on a number of dimensions, spanning all 50 states, and the video transcripts I collected span over 10 years. While some of these videos include the entirety of the religious service, my analysis focuses on “sermon” transcripts, defined here as the portion of the service where the religious leader (i.e. pastor or priest) is speaking on a topic specific to that particular service.

I rely on text analysis of the sermon transcripts to understand how politics are discussed in religious services. Text analysis is a set of computational techniques for reading, classifying, and sorting information from written texts, often at a larger scale than what would be feasible for a researcher to read and analyze themselves. In this project, I am particularly looking at differences in the frequency and context in which the word “racism” is used. (I also include mentions of the terms “racist” and “racial,” but I will collectively refer to these terms as mentions of “racism” throughout this post.)

In the above figure, I plot the fraction and number of sermons that mention one of these terms. On average, about 8% of sermons mention racism. Before the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement, an average of 5% of sermons mentioned racism. However, there is a substantial increase in the number of sermons that mention racism around June 2020, where about 25% of sermons mentioned racism. In the period following, roughly 10% of sermons mention racism.

Next, I examine how clergy discuss racism through the use of word embeddings. A word embedding is a numerical representation of a word that preserves some semantic meaning. This means that words that are associated in real-world contexts are numerically closer together in their word embedding representation. An example of how political scientists have used word embeddings is to analyze how Republicans and Democrats in Congress differ in their discussions of immigration. For Republicans, the term immigration is more closely related to the term “enforce,” and for Democrats, immigration is understood more in terms of “reform.”

For my application, I am viewing word embeddings as a representation of how clergy understand the causes of and solutions to racism. I can also test whether racism is viewed as an individual or systemic concern in these messages. I find that Protestant congregations are more likely than Catholic congregations to understand racism in individualistic terms (such as “you” and “I”), and Catholic congregations are more likely than Protestant congregations to understand racism in systemic terms such as “injustice.”

Using this method of word embeddings, I can also find excerpts from the sermons that are, on average, the best representation of how racism is discussed across different denominations. The most representative example of how racism is mentioned in the non-denominational and the mainline protestant congregations in my sample is the following excerpt from a sermon delivered in a large, non-denominational congregation in August 2020:

“There are differences between us but God says those things don’t have to stay between us, and so there is a terrible hatred. If you think racism is a problem today, you’re right, but it can’t hold a candle to the level of racism that was present between Jew and Gentile.”

For evangelical congregations, the most representative example comes from a sermon delivered in June 2020, in a medium-sized evangelical church:

“If you think about it, we would solve racism in America in one generation if we would have Christ-centered homes. We would, racism just wouldn’t exist in our country anymore largely. So let’s pray for healing in our country. Father God, we lift up our country to you and the people in our country, our leaders Lord, our police officers, and our African-American brothers and sisters…”

These examples support arguments among scholars that many white Christians have difficulty acknowledging racism as a system of inequality and injustice because individualism is emphasized as a theological commitment. W.E.B. DuBois viewed religion as integral to U.S. race relations. Indeed, the Black church has long been viewed as a central institution for providing civic resources to its congregants. However, DuBois aptly viewed the white church as a space where white supremacy is nurtured, by reimagining our nation’s legacy of racism or by ignoring the issue altogether.

However, my research agenda is concerned not only with diagnosing the ways in which religion in white Christian contexts can perpetuate racial injustice, but also how it may play a crucial part in motivating congregants to pursue justice. Another example from the sermons—a prayer delivered in a Catholic mass in January 2021—demonstrates a more collective, action-based discussion of racism:

“Christ freed humanity from its slavery to darkness. May Christian communities deepen their commitment to racial equality and racism out of love for the one God and Creator of all, we pray to the Lord. Lord hear our prayer.”

While Catholic congregations in my data were more likely to discuss racism in systemic terms than Protestant congregations, there is evidence across all traditions of both individual and systemic understandings of racism. Documenting these discussions is important for gaining a better understanding of how Americans understand and engage with questions of racial justice.

In other research projects, I argue that religious identity is actually a crucial component of white Christians’ racial attitudes. If religion is an important factor in how a large portion of Americans understand U.S. racial politics, then perhaps we can also look to religion to understand how to build support for policies seeking to remedy racial equality.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

Shayla Olson is a PhD student of American Politics and Quantitative Methods in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan. Her broad research interests fit within the fields of American political behavior and public opinion, with a focus on the intersection of race and religion in the United States. She is particularly interested in how local church contexts and clergy communication influence political and racial attitudes. A Next Generation scholar of the Institute for Social Research, Shayla Olson is the recipient of the Hanes Walton Jr. Endowment for Graduate Study in Racial and Ethnic Politics at the Center for Political Studies.

Hanes Walton, Jr. of the Center for Political Studies transformed the study of Black politics and helped establish it as a subfield of political science. The 2024 Hanes Walton Jr. Lecture at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research will be presented by Christian Davenport on Feb. 1.

Oct 31, 2023 | ANES, Economics, Elections, expert analysis, International, National, Policy, Social Policy

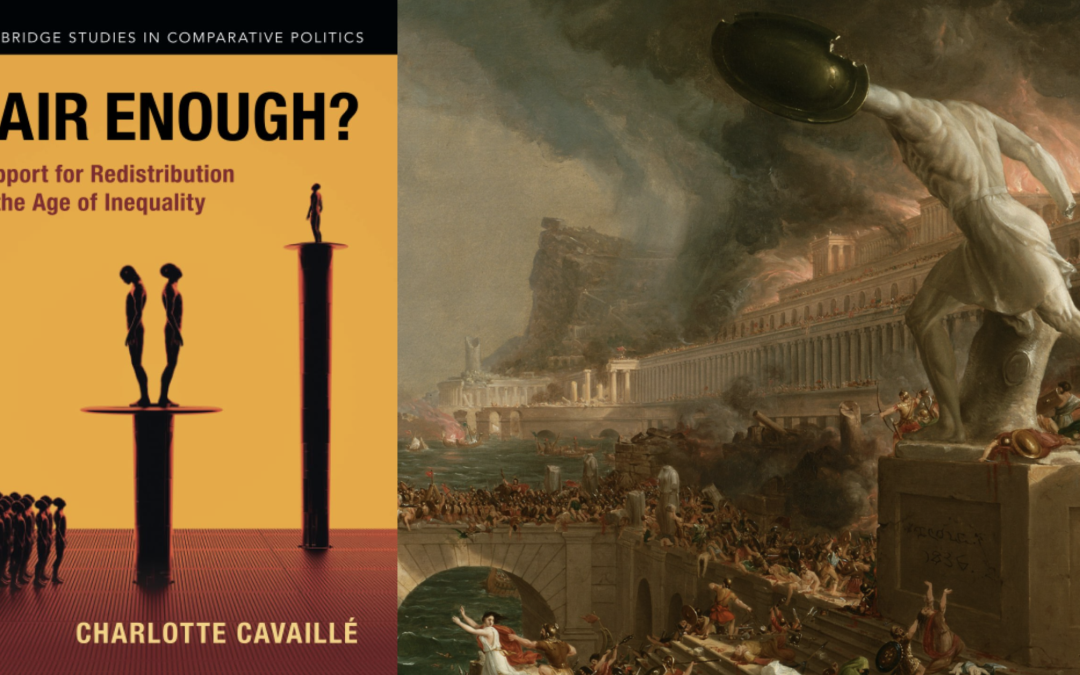

In the past, excessive economic inequality has ended… badly. As Charlotte Cavaillé points out in her new book that studies the public’s reaction to rising inequality, “only mass warfare, a state collapse, or catastrophic plagues have significantly altered the distribution of income and wealth.” Will this time be different?

Through income redistribution, democratic and political institutions today have a clear mechanism to peacefully address income inequality if voters demand it. Still, as highlighted by Cavaille in Fair Enough?: Support for Redistribution in the Age of Inequality (Cambridge University Press), greater wealth and income inequality are not leading to greater demand for an egalitarian policy response as many would expect.

Cavaillé reports there is little evidence of rising support for redistribution, especially among the worse off. Consider public opinion in the two Western countries with the sharpest increase in income inequality: In Great Britain, public support for redistribution is decreasing, and in the United States, the gap between the attitudes of low-income and high-income voters is narrowing. What, asks Cavaillé, can we conclude about public opinion’s role as a countervailing force to rising inequality?

Based on Cavaillé’s doctoral work, Fair Enough? introduces a framework for studying mass attitudes toward redistributive social policies. Cavaillé shows that these attitudes are shaped by at least two motives: material self-interest and fairness concerns. People support policies that would increase their own expected income. On the other hand, they also support policies that, if implemented, “would move the status quo closer to what is prescribed by shared norms of fairness.” Material interest comes most into play when policies have large material consequences, according to Cavaillé, but in a world of high uncertainty and low personal stakes, considerations of fairness trump considerations about one’s personal pocketbook.

Based on Cavaillé’s doctoral work, Fair Enough? introduces a framework for studying mass attitudes toward redistributive social policies. Cavaillé shows that these attitudes are shaped by at least two motives: material self-interest and fairness concerns. People support policies that would increase their own expected income. On the other hand, they also support policies that, if implemented, “would move the status quo closer to what is prescribed by shared norms of fairness.” Material interest comes most into play when policies have large material consequences, according to Cavaillé, but in a world of high uncertainty and low personal stakes, considerations of fairness trump considerations about one’s personal pocketbook.

How fair is it for some to make a lot more money than others? How fair is it for some to receive more benefits than they pay in taxes? Cavaillé emphasizes two norms of fairness that come into play when we think about such questions: proportionality, where rewards are proportional to effort and merit, and reciprocity, where groups provide basic security to members that cooperatively contribute. Policy disagreement arises because people hold different empirical beliefs regarding how well the status quo aligns with what these norms of fairness prescribe.

With fairness reasoning in the picture, Cavaillé writes, “baseline expectations are turned on their heads: Countries that are more likely to experience an increase in income inequality are also those least likely to interpret this growth as unfair.”

Should we expect growing support for redistribution to be a driving force behind policy change in the future? A change in aggregate fairness beliefs, Cavaillé argues, will require a perfect storm: a discursive shock that repeatedly exposes people to critiques of the status quo as unfair on the one hand, and a large subset of individuals whose own individual experience predispose them to accept these claims as true on the other. Policy changes in postindustrial democracies are possible, Cavaillé concludes– but they are unlikely to be in response to a pro-redistribution shift in public opinion.

Charlotte Cavaillé is an assistant professor of public policy at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. Her dissertation, on which ‘Fair Enough’ is based, received the 2016 Mancur Olson Best Dissertation Award.

Charlotte Cavaillé is an assistant professor of public policy at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. Her dissertation, on which ‘Fair Enough’ is based, received the 2016 Mancur Olson Best Dissertation Award.

Tevah Platt and Charlotte Cavaillé contributed to the development of this post.

May 11, 2023 | Elections, National, Policy, Social Policy

Post by Joshua Thorp

The 20th century Disability Rights Movement (DRM) is among the most successful and durable mass protest movements in American political history. Throughout the 20th century, DRM activists fought for equal political and economic rights– the desegregation of classrooms and public accommodations, the dismantling of coercive residential institutions, and an accessible built environment. Disabled activists and their allies occupied warehouses and university campuses, chained themselves to city buses, and took sledgehammers to inaccessible street curbs in an effort to make their voices heard. These remarkable episodes of political cohesion culminated in the 1990 passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a bill heralded by senator Tom Harkin, its chief congressional champion, as “the emancipation proclamation for people with disabilities.”

Used by permission. © Tom Olin Collection, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections, The University of Toledo Libraries.

Despite the prominence of disability in American political history, political scientists have only a thin understanding of how disability shapes political behavior. For the most part, existing research focuses on election accessibility and emphasizes the role of disability in curbing political participation. Several studies find that despite being no less interested in politics, people with disabilities are substantially less likely to turn out to vote than their non-disabled peers.

However, researchers have largely overlooked the potential impact of disability on political psychology. In particular, we don’t know whether disabled Americans see their disability as a politically meaningful feature of their social identities, or whether disability might serve as a basis for political cohesion or collective action. While the history of disability rights activism suggests disability may be politically mobilizing for a small minority of activists, less is known about whether or to what extent disability may also shape political identity in the mass public.

In a recent working paper, I find that disability is indeed an important dimension of political identity for many disabled Americans.

While disabled Americans do not appear mobilized along party lines, a sense of belonging to the disability community is associated with ideological liberalism and support for a range of social and redistributive policies.

Measuring disability as a social identity

I used an online survey of 700 Americans with disabilities to investigate two questions: Who embraces disability as a social identity? And how does identifying as a person with disability shape political attitudes? To collect the sample for this study fielded by Forthright Panels, I screened participants using the same measure of functional disability used by the U.S. Census and the CDC. I asked respondents a range of questions about their everyday experience of disability. I asked them how old they were when they first acquired their disability, how visible or noticeable their disability is by others, and how much functional limitation they experience in everyday life. Then, I asked respondents a series of questions about the degree to which their disability shapes their social identity: their sense of who they are as individuals and their place in the social world.

I compiled these items into a new measure of disability as a social identity– what I call the “Disability ID” scale. Those who score higher on the Disability ID scale consider disability to be an important feature of their personal identity, and place a high value on belonging to the disability community. A sizable minority of Americans with disabilities, about 35%, fall “high” on this scale.

Who embraces disability as a social identity?

I looked at the various characteristics that are associated with higher scores on the Disability ID scale. This analysis yielded two main findings. First, Disability ID is closely tied to impairment characteristics. Respondents with more severe, visible, and long-standing impairments were all more likely to report strong Disability ID. Second, Disability ID is stronger among those who participate in social and political institutions for people with disabilities. Specifically, Disability ID was stronger among those who reported receiving disability accommodations at school or at work, and among those who reported receiving financial assistance from the government on account of their disability.

How does Disability ID shape political attitudes?

Next, I wanted to understand how Disability ID shapes political outcomes. I first looked at the relationship between Disability ID and two key outcomes of interest to political scientists: ideology (liberal or conservative), and partisanship (Democrat or Republican).

The results of this analysis were intriguing. On the one hand, those higher in Disability ID tend to be more politically liberal. On the other hand, Disability ID has no discernible impact on political partisanship. In other words, those who identify strongly with their disability tend to support ideas often associated with liberalism, like government support for social services, but aren’t more likely to identify as Democrats.

I also wanted to understand the potential impacts of Disability ID on policy preferences. Given the particular forms of social and economic disadvantage that accompany disability, I predicted that Disability ID would be associated with support for government policies aimed at improving material well-being for people with disabilities. To test this prediction, I asked participants a series of questions about their level of support for a variety of social and redistributive policies.

A clear pattern of results emerged. Disability ID is strongly positively associated with support for a range of redistributive policies, especially those aimed at increasing financial security, public safety, and access to healthcare. In fact, in several instances the magnitude of the effect of Disability ID on policy attitudes is similar to that of explicitly political variables, such as political partisanship and ideology. On the other hand, Disability ID has relatively little impact on attitudes toward policies theoretically more peripheral to disabled Americans, such as public schools or border security.

Validity testing

To test the validity of these results, I conducted a similar analysis using data from the 2022 Cooperative Election Study (CES), a prominent national political survey fielded by YouGov and researchers from Harvard University. Unlike the Forthright Panels study, the CES survey was collected in two waves, where the same set of participants were interviewed before and after the 2022 midterm elections. I included questions about Disability ID on the pre-election survey fielded in the fall, and questions about policy attitudes on the post-election survey fielded in January 2023. This survey design allowed me to conduct a stronger test of the relationship between Disability ID and policy attitudes. By asking participants about their policy preferences in the post-election survey, I am able to observe the relationship between Disability ID and political attitudes in a context where participants have not already been primed to think about their disability.

Results from the CES mirror those found in the Forthright study. Again, Disability ID is strongly positively associated with support for redistributive policies, most notably those aimed at increasing financial security and access to healthcare. Furthermore, as in the Forthright Study, the magnitude of these effects is often similar to that of explicitly political variables, such as political partisanship and ideology.

Why does this matter?

These results should encourage researchers to think differently about the role of disability in shaping political behavior. More than 30 years after the passage of the ADA, disability remains an important dimension of socioeconomic inequality and disadvantage. People with disabilities are roughly twice as likely as their non-disabled peers to be unemployed and living in poverty, and are nearly four times as likely to be victims of violent crime. Addressing these inequalities is likely to require political engagement and collective action. While existing work has emphasized the role of disability in curbing political participation, these results suggest that for many disabled Americans, a shared social identity as members of the disability community may be an important source of political cohesion and empowerment.

Joshua Thorp is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. His research focuses on political psychology in the United States and other developed democracies, with a particular focus on the politics of disability. Thorp’s dissertation examines disability as a dimension of political identity in the United States. He is an Institute for Social Research Next Generation scholar at the Center for Political Studies, and was the recipient of the 2022 Converse-Miller fellowship in American political behavior.

Joshua Thorp is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. His research focuses on political psychology in the United States and other developed democracies, with a particular focus on the politics of disability. Thorp’s dissertation examines disability as a dimension of political identity in the United States. He is an Institute for Social Research Next Generation scholar at the Center for Political Studies, and was the recipient of the 2022 Converse-Miller fellowship in American political behavior.

The Forthright survey was generously funded by the Center for Political Studies (CPS) and the Rapoport Family Foundation. The CES data was collected as part of the University of Michigan team module of the Cooperative Election Study at CPS, led by Donald Kinder.

Tevah Platt and Julia Lippman contributed to the development of this post.

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have  Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.

Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

Based on Cavaillé’s doctoral work, Fair Enough? introduces a framework for studying mass attitudes toward redistributive social policies. Cavaillé shows that these attitudes are shaped by at least two motives: material self-interest and fairness concerns. People support policies that would increase their own expected income. On the other hand, they also support policies that, if implemented, “would move the status quo closer to what is prescribed by shared norms of fairness.” Material interest comes most into play when policies have large material consequences, according to Cavaillé, but in a world of high uncertainty and low personal stakes, considerations of fairness trump considerations about one’s personal pocketbook.

Based on Cavaillé’s doctoral work, Fair Enough? introduces a framework for studying mass attitudes toward redistributive social policies. Cavaillé shows that these attitudes are shaped by at least two motives: material self-interest and fairness concerns. People support policies that would increase their own expected income. On the other hand, they also support policies that, if implemented, “would move the status quo closer to what is prescribed by shared norms of fairness.” Material interest comes most into play when policies have large material consequences, according to Cavaillé, but in a world of high uncertainty and low personal stakes, considerations of fairness trump considerations about one’s personal pocketbook. Charlotte Cavaillé is an assistant professor of public policy at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. Her dissertation, on which ‘Fair Enough’ is based, received the 2016 Mancur Olson Best Dissertation Award.

Charlotte Cavaillé is an assistant professor of public policy at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. Her dissertation, on which ‘Fair Enough’ is based, received the 2016 Mancur Olson Best Dissertation Award.

Joshua Thorp is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. His research focuses on political psychology in the United States and other developed democracies, with a particular focus on the politics of disability. Thorp’s dissertation examines disability as a dimension of political identity in the United States. He is an Institute for Social Research Next Generation scholar at the Center for Political Studies, and was the recipient of the 2022 Converse-Miller fellowship in American political behavior.

Joshua Thorp is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan. His research focuses on political psychology in the United States and other developed democracies, with a particular focus on the politics of disability. Thorp’s dissertation examines disability as a dimension of political identity in the United States. He is an Institute for Social Research Next Generation scholar at the Center for Political Studies, and was the recipient of the 2022 Converse-Miller fellowship in American political behavior.