Top 10 Most-Viewed CPS Blog Posts in 2017

post developed by Catherine Allen-West

Since its establishment in 2013, a total of 137 posts have appeared on the Center for Political Studies (CPS) Blog. As we approach the new year, we look back at 2017’s most-viewed posts. Listed below are the posts that you, our dear readers, found most interesting on the blog this year.

What makes a political issue a moral issue? by Katie Brown and Timothy Ryan (2014)

There are political issues and then there are moral political issues. Often cited examples of the latter include abortion and same sex marriage. But what makes a political issue moral?An extensive literature already asserts a moral vs. not moral issue distinction. Yet, there is no consensus in how to distinguish between moral and non-moral political issues. Further, trying to sort issues into these categories proves challenging.

There are political issues and then there are moral political issues. Often cited examples of the latter include abortion and same sex marriage. But what makes a political issue moral?An extensive literature already asserts a moral vs. not moral issue distinction. Yet, there is no consensus in how to distinguish between moral and non-moral political issues. Further, trying to sort issues into these categories proves challenging.

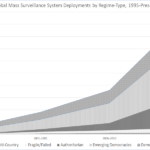

The Spread of Mass Surveillance, 1995 to Present by Nadiya Kostyuk and Muzammil M. Hussain (2017)

By closely investigating all known cases of state-backed cross-sector surveillance collaborations, our findings demonstrate that the deployment of mass surveillance systems by states has been globally increasing throughout the last twenty years. More importantly, from 2006-2010 to present, states have uniformly doubled their surveillance investments compared with the previous decade.

By closely investigating all known cases of state-backed cross-sector surveillance collaborations, our findings demonstrate that the deployment of mass surveillance systems by states has been globally increasing throughout the last twenty years. More importantly, from 2006-2010 to present, states have uniformly doubled their surveillance investments compared with the previous decade.

Why do Black Americans overwhelmingly vote Democrat? by Vincent Hutchings, Hakeem Jefferson and Katie Brown (2014)

In 2012, Barack Obama received 93% of the African American vote but just 39% of the White vote. This 55% disparity is bigger than vote gaps by education level (4%), gender (10%), age (16%), income (16%), and religion (28%). And this wasn’t about just the 2012 or 2008 elections, notable for the first appearance of a major ticket African American candidate, Barack Obama. Democratic candidates typically receive 85-95% of the Black vote in the United States. Why the near unanimity among Black voters?

Measuring Political Polarization by Katie Brown and Shanto Iyengar (2014)

Both parties moving toward ideological poles has resulted in policy gridlock (see: government shutdown, debt ceiling negotiations). But does this polarization extend to the public in general? To answer this question, Iyengar measured individual resentment with both explicit and implicit measures.

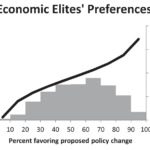

Is policy driven by the rich, or does government respond to all? by Catherine Allen-West (2016)

The enthusiasm for both Trump and Sanders’ messages about the influence of money in politics brings up an important question: Is policy driven by the rich, or does government respond to all? Political scientists have long been interested in identifying to what degree wealth drives policy, but not all agree on it’s impact.

The enthusiasm for both Trump and Sanders’ messages about the influence of money in politics brings up an important question: Is policy driven by the rich, or does government respond to all? Political scientists have long been interested in identifying to what degree wealth drives policy, but not all agree on it’s impact.

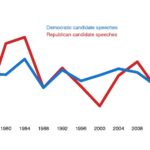

Exploring the Tone of the 2016 Election by U-M undergraduate students Megan Bayagich, Laura Cohen, Lauren Farfel, Andrew Krowitz, Emily Kuchman, Sarah Lindenberg, Natalie Sochacki, and Hannah Suh, and their professor Stuart Soroka (2017)

Political economists often theorize about relationships between politics and macroeconomics in the developing world; specifically, which political or social structures promote economic growth, or wealth, or economic openness, and conversely, how those economic outcomes affect politics. Answering these questions often requires some reference to macroeconomic statistics. However, recent work has questioned these data’s accuracy and objectivity. An under-explored aspect of these data’s limitations is their instability over time.

Political economists often theorize about relationships between politics and macroeconomics in the developing world; specifically, which political or social structures promote economic growth, or wealth, or economic openness, and conversely, how those economic outcomes affect politics. Answering these questions often requires some reference to macroeconomic statistics. However, recent work has questioned these data’s accuracy and objectivity. An under-explored aspect of these data’s limitations is their instability over time.

Crime in Sweden: What the Data Tell Us by Christopher Fariss and Kristine Eck (2017)

In a recent piece in the Washington Post, we addressed some common misconceptions about what the Swedish crime data can and cannot tell us. However, questions about the data persist. These questions are varied but are related to two core issues: (1) what kind of data policy makers need to inform their decisions and (2) what claims can be supported by the existing data.

Moral conviction stymies political compromise by Katie Brown and Timothy Ryan (2014)

Ryan’s overarching hypothesis boils non-compromise down to morals: a moral mindset orients citizens to oppose political compromises and punish compromising politicians. There are all kinds of issues for which some citizens seem resistant to compromises: tax reform, same-sex marriage, collective bargaining, etc. But who is resistant? Ryan shows that part of the answer has to do with who sees these issues through a moral lens.

Ryan’s overarching hypothesis boils non-compromise down to morals: a moral mindset orients citizens to oppose political compromises and punish compromising politicians. There are all kinds of issues for which some citizens seem resistant to compromises: tax reform, same-sex marriage, collective bargaining, etc. But who is resistant? Ryan shows that part of the answer has to do with who sees these issues through a moral lens.

Does the order of names on a ballot affect vote choice? by Katie Brown and Josh Pasek (2013)

Ballots list all candidates officially running for a given office so that voters can easily choose between them. But could the ordering of candidate names on a ballot change some voters’ choices?

Ballots list all candidates officially running for a given office so that voters can easily choose between them. But could the ordering of candidate names on a ballot change some voters’ choices?

Inside the American Electorate: The 2016 ANES Time Series Study by Catherine Allen-West, Megan Bayagich and Ted Brader (2017)

Since 1948, the ANES- a collaborative project between the University of Michigan and Stanford University- has conducted benchmark election surveys on voting, public opinion, and political participation. This year’s polarizing election warranted especially interesting responses.