Sep 25, 2014 | Profile

This post is a special edition of our researcher profile series. We’re very pleased to welcome Stuart Soroka to the Center for Political Studies (CPS)!

Post developed by Katie Brown and Stuart Soroka.

Stuart Soroka’s work has always involved the interactions between mass media, the public, and government. His early work looked at agenda-setting — the power of media content to influence what people think about, simply by presenting stories on certain topics. Instead of focusing on news content, however, Soroka looked at the potential for politically-relevant agenda-setting in feature films. When issues appear in movies, do the public and politicians then become more interested in them? (As an example, think about the release of Jurassic Park as potentially spurring interest and investment in paleontology.) His work in this area led to an interest in agenda-setting more broadly, and a doctoral dissertation on issue attentiveness from his time at the University of British Columbia.

Stuart Soroka’s work has always involved the interactions between mass media, the public, and government. His early work looked at agenda-setting — the power of media content to influence what people think about, simply by presenting stories on certain topics. Instead of focusing on news content, however, Soroka looked at the potential for politically-relevant agenda-setting in feature films. When issues appear in movies, do the public and politicians then become more interested in them? (As an example, think about the release of Jurassic Park as potentially spurring interest and investment in paleontology.) His work in this area led to an interest in agenda-setting more broadly, and a doctoral dissertation on issue attentiveness from his time at the University of British Columbia.

Since then Soroka’s work has focused on a new set of issues related to interactions between government, publics, and media. One stream of research asks: when do politicians agree and act in accordance with public opinion, and how do political institutions and media systems moderate this relationship? Another body of work is focused on the sources of public support for redistributive policy, with a particular interest on the potential tensions between redistribution and ethnic diversity. And most recently, his efforts have examined the sources and consequences of negativity biases in political communication and political behavior.

With this research agenda, Soroka has published four books and more than 50 journal articles and book chapters. He was Assistant Professor, then Associate Professor, and then full Professor of Political Science at McGill University. He recently joined the Center for Political Studies (CPS), department of Communication Studies, and department of Political Science at the University of Michigan. At Michigan, he plans to further extend his work on political representation, negativity biases, and the impact of emotion in both news and entertainment media.

Sep 18, 2014 | Foreign Affairs, International, Profile

Post developed by Katie Brown and Nahomi Ichino.

This post is a special edition of our researcher profile series. We’re very pleased to welcome Nahomi Ichino to the Center for Political Studies (CPS)!

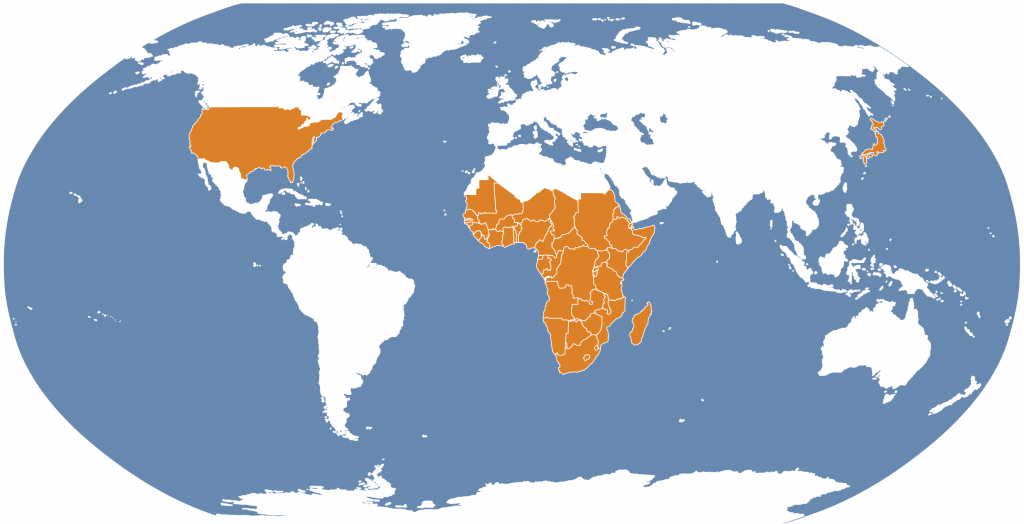

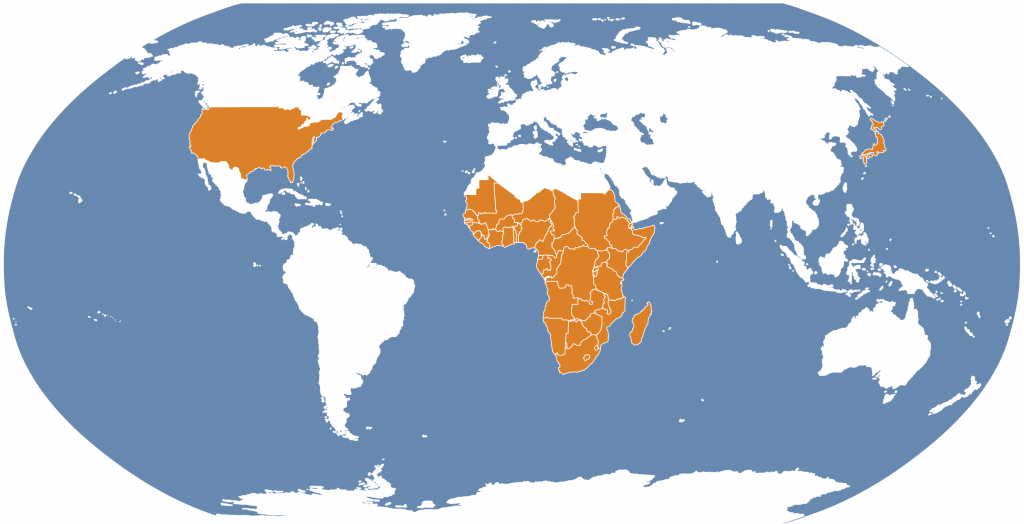

Ethnic politics and voter behavior in developing countries have long fascinated Nahomi Ichino. She partly attributes this to the relative homogeneity of Japan. The idea that people could be divided across many different ethnic groups and that this could be a major impediment for people to work together to make decisions for society as a whole seemed foreign and therefore intriguing to Ichino. News coverage of the 1983-1985 famine in Ethiopia sparked her interest in developing countries and Africa in particular.

As an undergraduate at Yale University, Ichino took a class on economic development in Africa with Christopher Udry. The course focused on how individuals in poor societies coped with risk and the lack of information as they made economic decisions like saving, borrowing, and lending money, or investing in the education of male and female children. Even as Ichino went onto study more macro-level political topics like political parties, she kept an interest in how individuals made political decisions in these environments.

After graduation with a degree in political science, Ichino continued to study this topic through graduate school, earning a Ph.D. in political science from Stanford University in 2008. She then joined the faculty at Harvard University’s Department of Government. Ichino continued to focus on sub-Saharan Africa during her time at Harvard, where she considered ethnic politics and voter behavior in developing democracies. With support from the National Science Foundation, she conducted research in Ghana, and produced a number of articles. Ichino has also conducted fieldwork in Uganda, Nigeria, Benin, Malawi, and Zambia. She also writes on methodological issues. Her work has been featured in the American Political Science Review and the American Journal of Political Science, among others.

Sep 10, 2014 | Conflict, Current Events, Elections, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Khalil Shikaki and Mark Tessler.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

This summer witnessed intense fighting between Israel and Gaza. With tens of thousands of rockets fired, the conflict killed more than 2,000 Palestinians, mostly civilians, and 80 Israelis, mostly soldiers. How has the most recent conflict affected Palestinian attitudes?

The Palestinian Center for Policy and Research (PCPSR) conducted a survey to gauge this impact. PCPSR is run by Khalil Shikaki. This year, Shikaki is a visiting scholar at the Center for Political Studies (CPS), working closely with CPS Research Professor and expert on the Middle East Mark Tessler. In this post, we offer results from PCPSR’s study along with insight from Tessler to understand the impact of the conflict on Palestinian public opinion.

PCPSR surveyed 1,270 adults in 127 locations across the West Bank and Gaza Strip between August 26 and August 30, 2014, coinciding with the first lasting ceasefire of the conflict. Results suggest that a significant majority (79%) of the Palestinian public views Hamas as the conflict’s winner. Just 3% believe Israel emerged victorious, while 17% believe both sides lost. Likewise, 79% blame Israel for starting this wave of fighting, while 86% support launching rockets at Israel from Gaza when under attack. As for the ceasefire agreement: 63% think it satisfies Palestinian interests.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

In addition to these conflict-specific findings, the PCPSR study also finds increasing support for Hamas among Palestinians to levels not seen since 2006. If elections occurred today, current Hamas deputy political bureau chief Ismail Haniyeh would easily win a presidential race against current president Mahoud Abbas. This is a massive shift in public opinion. Tessler notes that before the most recent conflict, support for Hamas was fading. Shikaki attributes this gain to the conflict, while predicting the Hamas support may wane as time passes. Tessler likewise cautions, “If things do settle down for a reasonable period and there is a new and stable status quo, any spike in Hamas popularity will probably drift back toward its ‘normal’ level based on what people favor and perceive with respect to political Islam, compromise with Israel, corruption and other issues that drive Palestinian politics in normal times.” Thus, the lingering effects of the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict will depend on whether or not the ceasefire continues.

Khalil Shikaki will give a talk at the CPS Interdisciplinary Workshop on Politics and Policy on September 17, 2014 in Room 6006 of the Institute for Social Research in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Sep 4, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, International, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Anne Pitcher.

Housing construction in Angola’s capital of Luanda; Photo credit: Anne Pitcher

Research and news about Africa tend to focus on failed states, poverty, and corruption. While these themes ring true for some African countries, others have witnessed the expansion of urban areas, rising demand for consumer goods, and the growth of a middle class. Angola has “done it all.” Angola has experienced conflict but has now transitioned to peace. It has high rates of poverty but also has an emerging middle class.

Located in Southern Africa, with the Atlantic Ocean to the West, Democratic Republic of the Congo to the North, Zambia to the East, and Namibia to the South, Angola achieved independence from Portugal in 1975 only to become embroiled in a decades long civil war. Further, as an ally of Russia and Cuba, Angola remained isolated from the Western world for the duration of the Cold War.

Due to political instability and isolation, Angola’s nearly 20,000,000 citizens have been largely ignored in rigorous analysis. In fact, Angola is one of the least researched places in the world. Although there are several reputable research institutions based in Angola, most major surveys of the continent, like those conducted by the Afrobarometer, World Bank, or the African Development Bank, do not include Angola. Meanwhile, the results of the Angolan government’s own first census data will not be released for several more years.

Owing to her research experience in Mozambique, another African country formerly colonized by the Portuguese, Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate Anne Pitcher decided to include Angola in her research beginning several years ago. Pitcher, also a Professor of African Studies and Political Science and Coordinator of the African Social Research Initiative, is interested in understanding patterns of goods distribution in Angola following the end of the civil war in 2002.

In particular, she wants to be able to explain why the government of this oil producing country had made a commitment to build a million homes for the urban poor and the middle class; how such an ambitious commitment is actually being realized in a country where revenues from oil completely dominate the Gross Domestic Product; and who is really benefiting from construction and sales in a place with a tightly knit elite and huge disparities in wealth.

To this end, Pitcher has teamed up with Angolan scholar Sylvia Croese and Allan Cain, the director of Development Workshop (a widely respected organization based in Luanda, Angola, and one of the few to attempt systematic studies of land, property rights, and patterns of urbanization in Angola). The researchers are currently conducting 200 tablet-based surveys of housing finance and satisfaction in Kilamba, a new city consisting of 20,000 units located on the outskirts of the capital city of Luanda. Financed by a 3.5 billion USD credit line from the Chinese government to the government of Angola, Kilamba is being built by the Chinese International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC) to house Angola’s growing middle class. Housing purchases are partly subsidized by the government and when fully occupied, Kilamba will house 150,000 people.

Conducting research in Angola has proven both easier and more difficult than expected. Pitcher anticipated that survey respondents might be reluctant to participate since Angola does not have a history of conducting public opinion surveys. Instead, she has found participants excited to voice their opinions. Pitcher attributes this eagerness to the limited avenues for self-expression in the relatively closed country. The survey’s timing has also tapped into the gradual opening of the society, as evidenced by support for the survey from the country’s Ministry of Urbanism and Housing. Yet the team has faced some obstacles. Building the participant pool has proven challenging, as the country lacks confirmed population data; exact occupancy rates in Kilamba are unknown; and there is very little existing background data from which to build hypotheses about how residents earn their incomes or finance purchases.

But so far, the survey team has persevered. Data collection ends this month, and the product will serve as some of the most comprehensive data of its sort ever collected in Angola (in addition to the still unreleased census). Beyond a number of questions drawn from Afrobarometer public opinion surveys conducted across the rest of Africa, the survey includes questions that have never been systematically asked about housing finance, satisfaction with housing, education, and commute times. It also measures public opinion on issues like the distribution of wealth, poverty, taxes, and unemployment.

A completed Kilamba housing development; Photo credit: Anne Pitcher

Pitcher believes that understanding real estate finance and the opinions of new middle class homeowners will offer valuable insights into the quickly evolving politics of the country. Why? The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) party has ruled the country since the nation’s independence in 1975. With the recent shift from a Marxist-Leninist one party system to multi-party politics, the MPLA wants to maintain power. Constructing houses is part of this effort. Among other models, the MPLA modeled this venture on Margaret Thatcher’s campaign to offer housing to Britain’s council residents in the 1980s. Thatcher hoped that providing housing would lead to more conservative and more loyal citizens. The MPLA may likewise hope that creating homeowners will create stability in a country marred by decades of war. Currently, many young people in Angola express great discontent, particularly with respect to a lack of housing. The study by Pitcher, Croese, and Cain will offer a better understanding of whether that discontent is being addressed or modified.

With data collection nearly complete, Pitcher is very excited to dive into the data. In the near future, the research team hopes to expand the scope of the survey to include additional types of urban housing such as social housing that is offered for free to those with minimal resources; self constructed housing built by individuals themselves; and cooperative private housing. Because the government is involved to varying degrees with each of these types, understanding the differences may not only shed light on politics and economics, but also offer insight on best practices with respect to housing finance and citizen satisfaction in developing, post-war countries.

Stuart Soroka’s work has always involved the interactions between mass media, the public, and government. His early work looked at agenda-setting — the power of media content to influence what people think about, simply by presenting stories on certain topics. Instead of focusing on news content, however, Soroka looked at the potential for politically-relevant agenda-setting in feature films. When issues appear in movies, do the public and politicians then become more interested in them? (As an example, think about the release of Jurassic Park as potentially spurring interest and investment in paleontology.) His work in this area led to an interest in agenda-setting more broadly, and a doctoral dissertation on issue attentiveness from his time at the University of British Columbia.

Stuart Soroka’s work has always involved the interactions between mass media, the public, and government. His early work looked at agenda-setting — the power of media content to influence what people think about, simply by presenting stories on certain topics. Instead of focusing on news content, however, Soroka looked at the potential for politically-relevant agenda-setting in feature films. When issues appear in movies, do the public and politicians then become more interested in them? (As an example, think about the release of Jurassic Park as potentially spurring interest and investment in paleontology.) His work in this area led to an interest in agenda-setting more broadly, and a doctoral dissertation on issue attentiveness from his time at the University of British Columbia.