Bureaucracy and Economic Markets: A Coevolutionary View of Development

by Catherine Allen-West

Political economists have long debated the causal relationship between good institutions—such as technocratic, Weberian bureaucracies—and economic development. Whereas some insist that good institutions must precede economic development, others assert that it is economic success that eventually leads to good institutions. So who’s right and who’s wrong?

Yuen Yuen Ang Faculty Associate at the University of Michigan’s Center for Political Studies answers this question using a novel, dynamic approach in a chapter entitled Do Weberian Bureacracies Lead to Markets or Vice Versa? A Coevolutionary Approach to Development. The chapter recently appeared in an edited volume, States in the Development World, that is the final product of a series of international workshops on state capacity hosted by Princeton University. The chapter is also included in the Working Paper Series of Stanford University’s Center for Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL).

Development as a Three-Step, Coevolutionary Sequence

Ang injects a novel perspective into this long-standing debate. She argues that development unfolds in a three-step coevolutionary sequence:

Harness weak institutions to build markets ➡️ emerging markets stimulate strong

institutions ➡️ strong institution preserve markets.

In this chapter, Ang demonstrates this argument using a historical comparison of three local states in China. She traces the mutual adaptation of state bureaucracies and industrial markets from 1978 (beginning of market reform) through 1993 (acceleration of market reform) to the present.

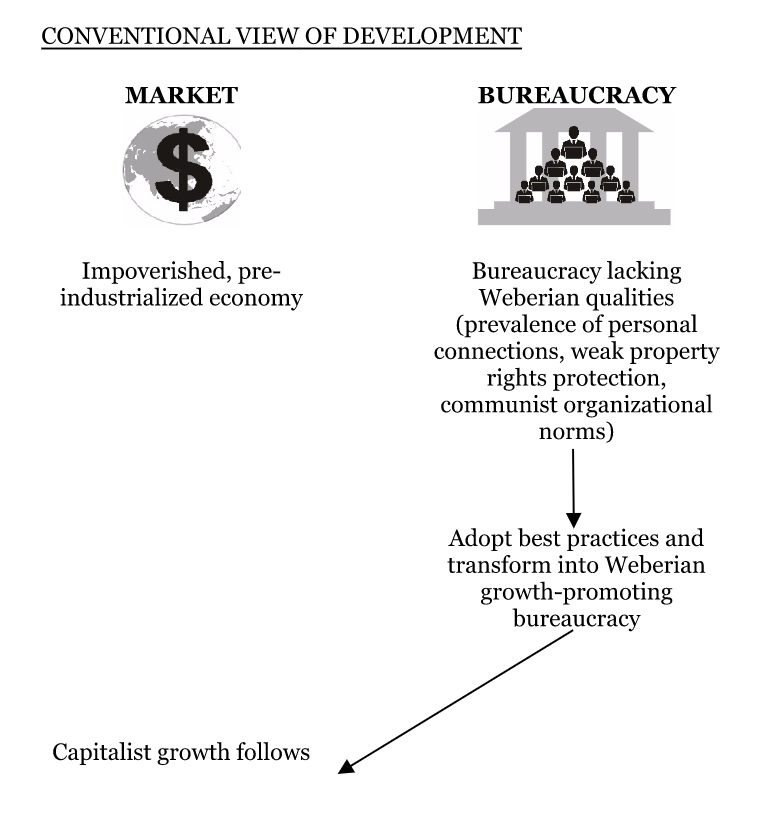

The political economies of all these locales have undergone radical transformation over the past four decades. According to the conventional view of development this process must have occurred by first establishing a fleet of new bureaucracies rather than relying on any existing systems. The process is depicted here:

Ang, however, reveals a surprisingly different—non-linear—story. She finds that Chinese locales built markets by first mobilizing the preexisting bureaucracy, left over from the Maoist era, to attract capitalist investments through distinctly non-Weberian modes of operation: non-specialized and non-impartial. Normally, features that violate Weberian best practices are dismissed as “weak” or “corrupt.” Yet weak institutions, Ang argues, are precisely the raw materials for building markets from the ground up.

From there, Ang says, the process of development continued. Once local markets took off, the emergence of markets altered the preferences and resources of local state actors. These changes led local governments to replace earlier unorthodox practices with more Weberian practices that serve to preserve established markets. Ang’s three-step coevolutionary sequence is summarized in the figure below.

Market-Building ≠ Market-Preserving

Ang’s theory of development draws a sharp distinction between the institutions that bolster emerging as opposed to mature markets, which she calls “market-building” and “market-preserving” institutions respectively. Thus far, existing theories have focused exclusively on “market-preserving” institutions. Ang calls attention to the neglected variety of “market-building” institutions.

This chapter offers a preview of Ang’s broader work, contained in her book, How China Escaped the Poverty Trap. Her book further unpacks the three-step coevolutionary sequence of development, with evidence not only from China but also other national cases (Europe, the U.S., Nigeria). It also details the distinct fieldwork strategies and analytic methods that she developed to map coevolutionary sequences.

Reviews of How China Escaped the Poverty Trap recently appeared in the Straits Times, Foreign Affairs, and World Bank Development Blog. Yongmei Zhou, the Co-Director of the World Development Report 2017, writes in her review:

“The first takeaway of the book, that a poor country can harness the institutions they have and get development going is a liberating message. Nations don’t have to be stuck in the “poor economies and weak institutions” trap. This provocative message challenges our prevailing practice of assessing a country’s institutions by their distance from the global best practice and ranking them on international league tables. Yuen Yuen’s work, in contrast, highlights the possibility of using existing institutions to generate inclusive growth and further impetus for institutional evolution.”

It is extremely promising that the development establishment questions its long-standing belief that conventionally good/strong institutions, benchmarked by Western practices, must be in place for markets to grow. Tremendous room for alternative methods of growth promotion opens up once academics and policymakers entertain the possibility that existing institutions in developing countries, even if they violate best practices, can be used to kick-start markets, as Professor Ang’s research reveals.

References

Ang, Y.Y. “Do Weberian Bureaucracies Lead to Markets or Vice Versa? A Coevolutionary Approach to DevelopmentM.” Chapter in Centeno, Kohli & Yashar (Eds.), States in the Developing World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Ang, Y.Y. How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, Cornell University Press, Cornell Studies in Political Economy, scheduled for release on September 6, 2016.

Ang, Y.Y. “Beyond Weber: Conceptualizing an Alternative Ideal-Type of Bureaucracy in Developing Contexts,” Regulation & Governance, 2016.