Nov 26, 2013 | Profile

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with William Zimmerman.

This post is part of a series that explores how Center for Political Studies (CPS) researchers came to their work.

As an undergraduate at Swarthmore College, William “Bill” Zimmerman studied under Kenneth Waltz, a key figure in the development of the field of International Relations. Zimmerman then went on to complete his Ph.D. at Columbia University.

As an undergraduate at Swarthmore College, William “Bill” Zimmerman studied under Kenneth Waltz, a key figure in the development of the field of International Relations. Zimmerman then went on to complete his Ph.D. at Columbia University.

Professor Zimmerman’s first book Soviet Perspectives on International Relations 1956-1967, based on his dissertation, follows the structure of Waltz’s book Man, the State, and War. But instead of talking about philosophers, Zimmerman’s book considers the emergence of International Relations as a discipline in the U.S.S.R.

With his first book in hand, Zimmerman felt moved to do something different. He especially wanted to journey where he could both do his research and his family could accompany him. In 1970, the U.S.S.R. was not an option. Zimmerman secured a Fulbright Fellowship and ventured to Yugoslavia with his family in tow. Around this time, he also became involved with a research project focused on Jews who migrated from the U.S.S.R. This research project became Zimmerman’s initial foray into survey research.

Then, in the late 1980s, the world changed. Mikhail Gorbachev became President of the U.S.S.R. and ushered in an era of openness with glasnost and perestroika. The U.S.S.R. collapsed. And it was now possible to conduct survey research in Russia. “The impossible,” as Zimmerman puts it, “was now possible.” And so he set out to conduct surveys in Russia. What was originally intended to be a single survey in 1993 was expanded and developed into a six wave panel study of Russian elites and conducted through 2012.

Over his illustrious career, Zimmerman has written or edited eight books and published more than 60 journal articles and book chapters. Zimmerman is now retired, holding the title of Research Professor Emeritus at the Center for Political studies. He jokes that he is “basically doing the same thing now, just without getting paid.” He especially appreciates his wife’s support in this regard, chuckling while stating that “she knew what she was getting into.” Looking back on his career, Zimmerman can see how his career path changed with the times. He started out as “the guy that studied Soviet foreign policy from afar” and then became “the guy doing surveys of Russian elites in Moscow.”

Nov 19, 2013 | CLEA, Profile, Student Experiences

Developed by Katie Brown and Josue Gomez.

This is the first post in a series about students working on research projects in the Center for Political Studies (CPS). Here, we profile Josue Gomez, whose work on the Constituency-Level Elections Archive (CLEA) helped influence his career path in political science.

Josue Gomez was raised in a farming community in southern Idaho, the son of a Mexican-American farm worker. The current debate on immigration policy, especially the relationship between the U.S. and Mexico, piqued his interest in politics. He enrolled at Boise State University — the first in his family to attend college — and majored in political science. As part of the McNair Scholars program supporting under-represented students, Josue was required to complete a summer research program prior to graduating. Josue and his advisor, Ross Burkhart, identified the University of Michigan as a good place to apply, and Josue was accepted as part of the Student Research Opportunity Program (SROP) at Michigan. Through the SROP program, he joined the Constituency-Level Elections Archive (CLEA) project as a research assistant in the Summer of 2012.

Josue Gomez was raised in a farming community in southern Idaho, the son of a Mexican-American farm worker. The current debate on immigration policy, especially the relationship between the U.S. and Mexico, piqued his interest in politics. He enrolled at Boise State University — the first in his family to attend college — and majored in political science. As part of the McNair Scholars program supporting under-represented students, Josue was required to complete a summer research program prior to graduating. Josue and his advisor, Ross Burkhart, identified the University of Michigan as a good place to apply, and Josue was accepted as part of the Student Research Opportunity Program (SROP) at Michigan. Through the SROP program, he joined the Constituency-Level Elections Archive (CLEA) project as a research assistant in the Summer of 2012.

CLEA is a repository of detailed election results from around the world which collects outcomes from lower house elections. CLEA provides opportunities for students to be involved at all stages of the data collection process, providing valuable experience and training for them. Working on research projects can be an excellent way for students to explore whether they would like to further their career in research and academia. Many of CLEA’s alumni have gone on to attend graduate school and obtained research-oriented jobs.

As part of his responsibilities on the CLEA project, Josue was assigned to work on Latin American and a few European countries. Given his fluency in Spanish and natural inclination to learn about these countries, Josue grew a strong connection to the project. Among the countries he was assigned to work on, he was encouraged to choose one to study in more depth. Chile was the largest country in Latin America that was not yet represented in CLEA, and Josue decided that it would be valuable for CLEA to include it. As Josue studied the intricacies and results of elections in Chile, he became interested in a broader research agenda concerning political parties and democratization. Prior to the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinoche, Chile had held elections After the dictatorship was removed, Chile began to hold elections again. In his studies, Josue began to wonder how relationships between parties and an old regime (in Chile’s case, the dictatorship) influence the performance of the parties in elections during and following the transition to democracy.

At the time, Josue was a senior at Boise State University. In his work on CLEA he identified what became a fundamental question for him: How do parties succeed in foundational elections? CLEA also helped him begin to answer this question.

As a McNair Scholar, Josue published a short article based on his work with CLEA. In the  paper, Josue lays out a spectrum of parties that exist in new democracies, in order to help understand why some parties are more successful than others. Focused on Latin America, Josue finds a relationship between party alignment in older regimes and success in new elections.

paper, Josue lays out a spectrum of parties that exist in new democracies, in order to help understand why some parties are more successful than others. Focused on Latin America, Josue finds a relationship between party alignment in older regimes and success in new elections.

Josue notes that political scientists and other researchers are always looking for reliable data like that provided by CLEA. By examining the electoral rules and election results from countries around the world, researchers can discover what electoral systems work better in certain regions and in certain time frames, investigate how political parties developed or declined, and seek to understand whether and why the democratic experience is working or not.

Josue’s experience in building social science infrastructure and his own research skills in his work with CLEA laid the foundation for his McNair Scholars paper, and has also influenced his academic path. The experience has led him to pursue a Ph.D.; he is currently enrolled as a graduate student in the Department of Political Science at The Ohio State University

Nov 14, 2013 | ANES, Michigan, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In June of this year, the Supreme Court of the United States maintained the legality of affirmative action programs at American colleges and universities – for now. The Supreme Court’s seven-to-one decision pushes American colleges and universities to prove the utility of affirmative action programs. The court declined to rule specifically on a case regarding the University of Texas at Austin’s affirmative action policy. This week, the UT Austin case was debated before a federal court.

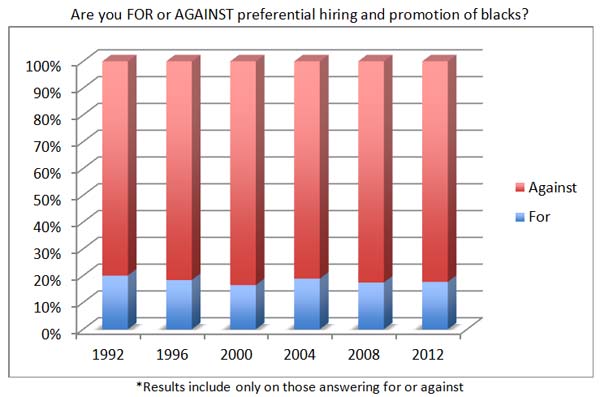

How does the American public feel about affirmative action, and has their support or opposition changed over time? The American National Election Studies (ANES) can be used to examine such trends. For 65 years, the ANES has interviewed a representative sample of voting age Americans on a variety of topics, including but not limited to voting and turnout, public policy support, societal values, and demographics. As ANES describes, the resulting data “inform the nation about itself.”

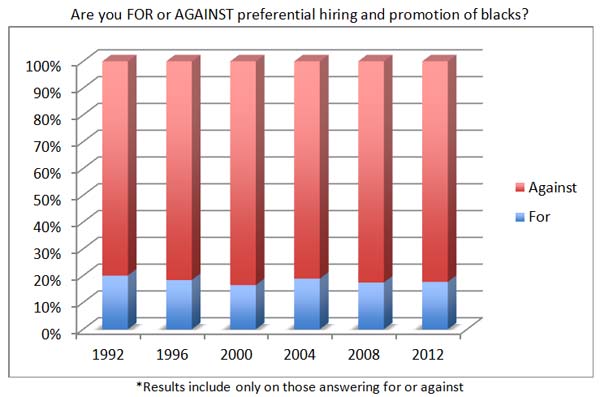

There are many ways to measure levels of support or opposition for affirmative action. Since 1992, ANES has asked the American voting age public whether it is “for or against” one type of affirmative action: preferential hiring and promotion of blacks. As the graph below illustrates, public opposition in the United States for this type of affirmative action appears both dominant and stable over the time period 1992-2012.

In 2012, ANES also asked a question about support or opposition for the use of quotas to admit black students to colleges and universities. The results were similar, with 77% of respondents opposing such a program and 23% of respondents being in support.

The latest Supreme Court ruling comes on the heels of a 2003 Supreme Court decision regarding the University of Michigan‘s use of affirmative action in its decision-making process for admitting students. The Court upheld the use of affirmative action by the University’s law school but negated the use of affirmative action in its undergraduate admissions. In 2006, voters from the state of Michigan voted in support of a ballot referendum, Proposition 2, which made affirmative action illegal in the state. Then in November of 2012, the state of Michigan’s 6th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Proposition 2. Last month, the constitutionality of Proposition 2 went before the Supreme Court of the United States.

The latest court proceedings suggest that the future of affirmative action remains unclear, but results from the ANES suggest that public opposition to affirmative action remains stable. Yet, no single question or two can encapsulate feelings toward an issue as complex as this one.

Nov 7, 2013 | Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with William Zimmerman.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In recent months, many U.S. headlines have cast Russia in a negative light. With the 2014 Winter Olympics set to take place in Sochi, Russia, worries about the host country’s homophobia and racism abound. A hunger strike by one imprisoned member of the band Pussy Riot brought the harsh labor camp sentences for the political activist punk rock band back into the news. And whistleblower Edward Snowden found asylum in Russia to avoid extradition to his native United States. Amid these negative stories, Russia played an instrumental role in disarming Syria’s Assad of his chemical weapons without resorting to militaristic retaliation. This peace brokering role culminated in a Nobel peace prize for the watch dog group brought in to oversee the process.

Stories about Russia, like these examples, often focus on President Vladimir Putin. Putin has solidified his power within Russia and abroad during his reign. In fact, Forbes named him the World’s Most Powerful Person for 2013.

But how do Russian’s feel about the trajectory of their government? Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor Emeritus William Zimmerman studies International Relations, with a specialty in Russia.

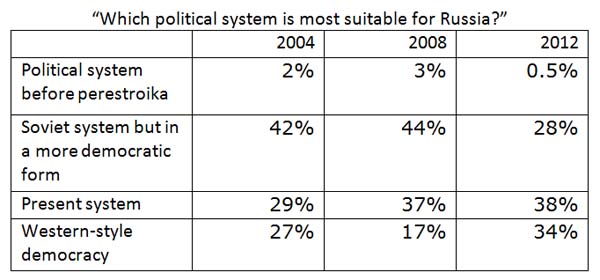

Over the period 1993-2012, Zimmerman has overseen a panel of six surveys of elites from Moscow – including heads of governmental departments, owners and executive officers of companies, media editors, leaders in the armed forces, and members of the legislature.

In his recent working paper – “2020 Vision: Russian elites in 2020 perspective: Political system preference and national interests” – Zimmerman considers the results of the survey as a way to map expectations of the future among Russian elites.

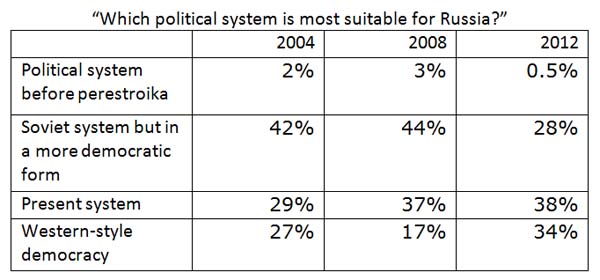

The three most recent surveys (in 2004, 2008, and 2012) suggest a trend among these elites toward support for Western-style democracy. Zimmerman projects that this support will continue to grow through 2020. The following table breaks down survey responses by year, illustrating the trend.

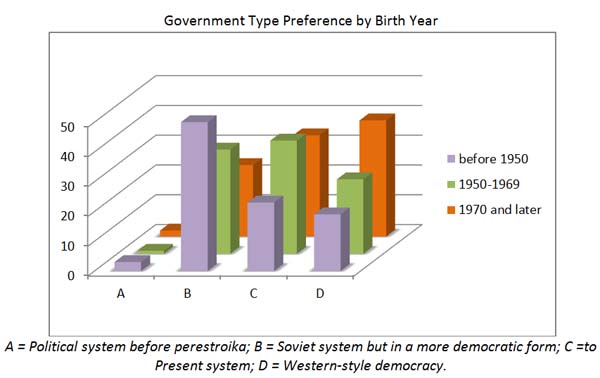

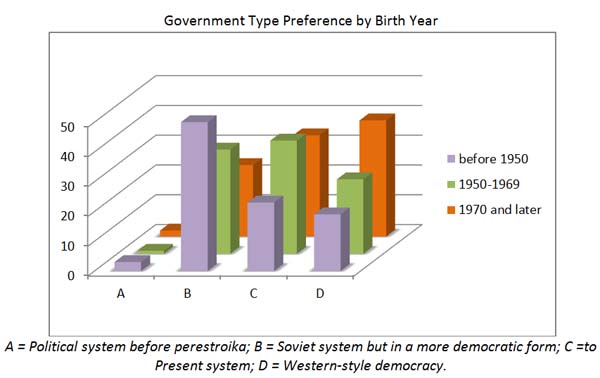

Interestingly, support for Western-style democracy is also more pronounced among younger Muscovite elites. The graph below breaks down support by birth year range (with the height of each column indicating the number of persons responding, not percentages).

Zimmerman ends with an interesting question: “Would the creation of a genuinely competitive party system – warts and all – boost support for what is after all a core element in Western political systems?” Interestingly, the paper notes that in the early years of his tenure, Putin spoke admiringly about such a system.

Nov 5, 2013 | Elections, National

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Josh Pasek.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

American elections are traditionally held the first Tuesday in November. On this first Tuesday in November, we present a post on ballots in honor of elections.

Ballots list all candidates officially running for a given office so that voters can easily choose between them. But could the ordering of candidate names on a ballot change some voters’ choices? A new study by Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate and Assistant Professor of Communication Josh Pasek suggests just such a possibility.

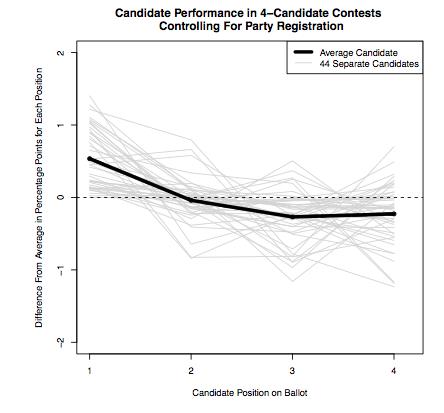

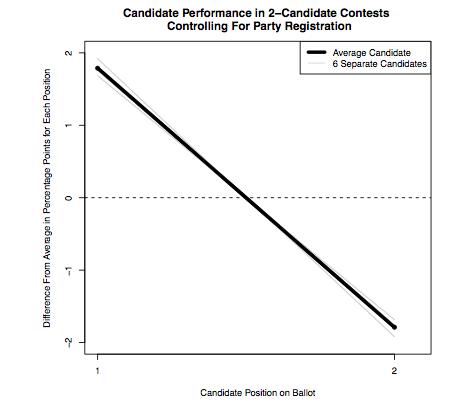

Pasek studies the impact of new media and psychological processes on political attitudes, public opinion, and political behavior. In a forthcoming paper – with Daniel Schneider, Jon Krosnick, Alexander Tahk, Eyal Ophir, and Claire Milligan – Pasek considers the effect of ballot ordering on election results.

The study uses data from all California elections between 1976 and 2006. California randomizes the order of candidate names on ballots by district, creating a natural chance to test this question.

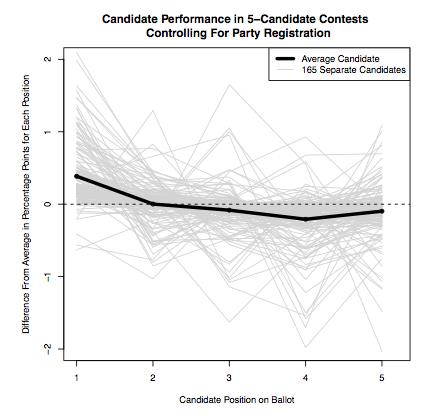

Pasek and his colleagues analyzed the data in a variety of ways. No matter the approach, candidates listed first on the ballot had a slight advantage. This effect was largest for races (1) with little publicity, (2) when more votes were cast, and (3) when there was a bigger win. These factors support the idea that name order may influence those with minimal information about or investment in the race.

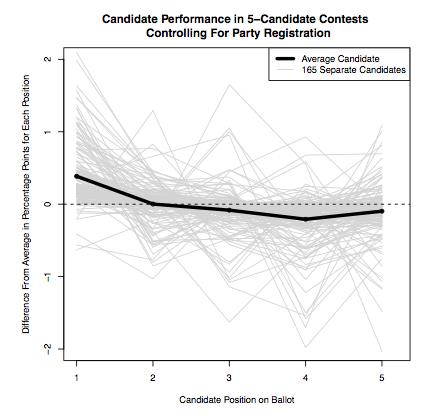

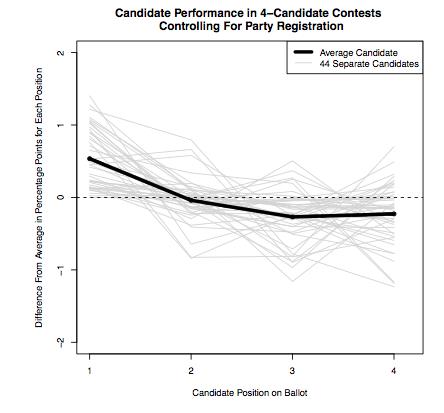

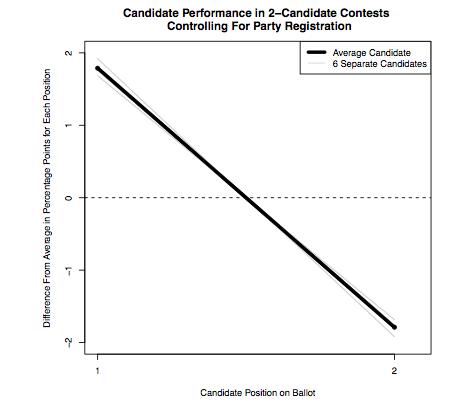

The graphs at the bottom of this post show this advantage for contests with (a) five candidates, (b) four candidates, and (c) two candidates. The horizontal axis shows the position of each candidate on the ballot. The vertical axis shows how that candidate’s votes would be expected to change. As we can see, candidates tend to perform best when listed in the first position on the ballot and worse when listed farther down on the ballot, with the exception of the last spot on the ballot where there is a slight rebound.

Although the overall size of the effect is small, Pasek notes that the size of the effect is far greater than the margin of victory in many elections. For example, George W. Bush beat Al Gore by less than 0.009 percent (a few hundred votes out of six million cast) in Florida in the 2000 election for the President of the United States. Randomizing the order of names on a ballot may therefore be important for ensuring a fair, democratic process.

a.

b.

c.

As an undergraduate at Swarthmore College, William “Bill” Zimmerman studied under Kenneth Waltz, a key figure in the development of the field of International Relations. Zimmerman then went on to complete his Ph.D. at Columbia University.

As an undergraduate at Swarthmore College, William “Bill” Zimmerman studied under Kenneth Waltz, a key figure in the development of the field of International Relations. Zimmerman then went on to complete his Ph.D. at Columbia University.