Aug 29, 2013 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Ken Kollman.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

On July 22, 2013, the European Union (EU) declared that the military wing of Hezbollah was now on its list of terrorist organizations. This reversal of policy has implications for Hezbollah and the EU’s influence in parts of the Middle East.

Three events precipitated the change in policy by the EU. First, while Hezbollah denies involvement, most blame people in the group for a 2012 bus bombing in Bulgaria. Second, Hezbollah forces are fighting on behalf of Assad in Syria, while the EU is openly supporting the Syrian rebels. Three, a Lebanese Swedish man on Hezbollah’s payroll was charged and sentenced in 2013 for planning to attack Israeli tourists in Cyprus.

The declaration of Hezbollah’s military wing as a terrorist group took longer than many expected and came belatedly after years of prodding by the United States government. Decisive foreign policy decision making of this kind is difficult to achieve in the EU given its lack of a centralized executive with well-defined responsibilities for foreign affairs.

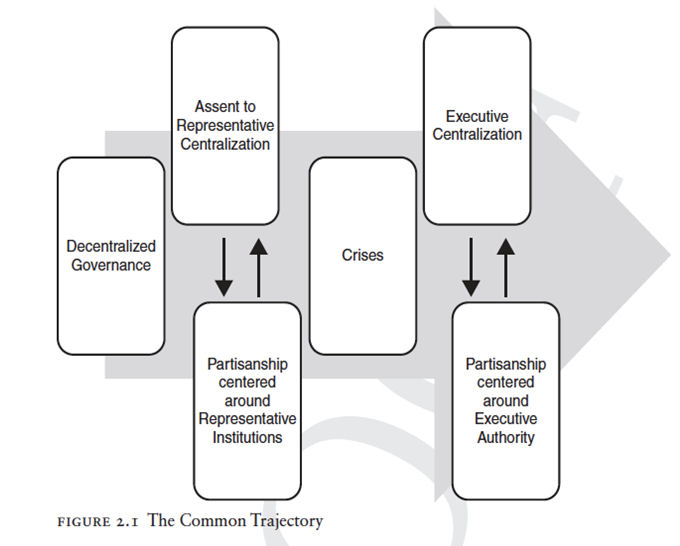

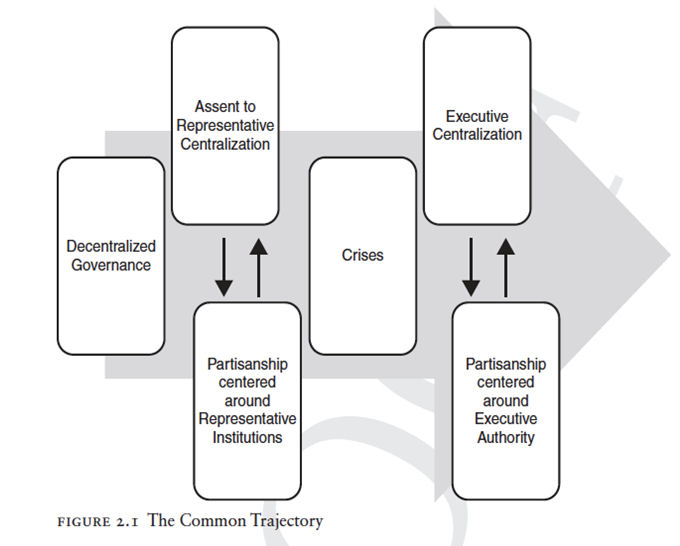

Ken Kollman, Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher and director of the International Institute at the University of Michigan, has a forthcoming book examining the histories of federated institutions like the EU to learn of the development of centralized executive power. In Perils of Centralization: Lessons from Church, State, and Corporation, Kollman dissects the histories of the U.S. government, the Roman Catholic Church, General Motors Corporation (GM), and the EU. In the book he argues that the EU is at a turning point. It has evolved what he calls representative centralization, which means that the countries of the EU still exert considerable authority over centralized decision-making. Unlike the U.S. government, which has tipped into what Kollman calls executive centralization, the EU countries, when they lack a consensus on matters like the Hezbollah listing, find many ways to delay unified decision-making. In the U.S. the subunit governments and subunit representatives have largely delegated to a single executive (the president) foreign policy decision-making power.

The Figure shown here from Kollman’s book shows the typical pattern for federations, but he notes that the EU is now poised between assent to representative centralization and executive centralization.

While Brussels exercises authority that supersedes a given nation on several key policy issues, the power is diffuse. When policy decisions are announced, for example, three or more leaders often stand behind the microphone, a symbol of both multiplicity and unclear jurisdictions. Executive power in the EU is not unified and often cannot be decisive.

The example of the lengthy process of Hezbollah’s listing and other similar examples showcase EU’s fragmented political power. Its halting evolution as a federated system leads to its precarious position as a potential player on the world stage.

Aug 26, 2013 | Profile

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Maris Vinovskis.

This is the first post in a series that explores how Center for Political Studies (CPS) researchers came to their work. And our first profile tells the fascinating path of CPS researcher, Professor of Public Policy, and Bentley Professor of History Maris Vinovskis.

Born in war torn Latvia in 1943, Vinovskis and his family were forced out by the impending Soviet invasion. Destined for Dresden, the bombings rerouted them to former Czechoslovakia. Unsafe there, too, the family made it to an American zone in Munich, where they spent 5 years in a camp of mostly Latvians displaced by the war. The Vinovskis family then moved to the United States, settling in rural Blair, Nebraska. Vinovskis started first grade with his sister. Knowing no English, “We sat through most of the classes without any idea of what was being discussed.” By second grade, Vinovskis understood the language and excelled, with the help of dedicated teachers. In 1957, his father, a lawyer back in Europe, took a job as a meatpacker and moved the family to Omaha. Vinovskis shares, “The continued economic challenges facing our family aroused my early interest in public policy, especially on how to help low-income families.”

Born in war torn Latvia in 1943, Vinovskis and his family were forced out by the impending Soviet invasion. Destined for Dresden, the bombings rerouted them to former Czechoslovakia. Unsafe there, too, the family made it to an American zone in Munich, where they spent 5 years in a camp of mostly Latvians displaced by the war. The Vinovskis family then moved to the United States, settling in rural Blair, Nebraska. Vinovskis started first grade with his sister. Knowing no English, “We sat through most of the classes without any idea of what was being discussed.” By second grade, Vinovskis understood the language and excelled, with the help of dedicated teachers. In 1957, his father, a lawyer back in Europe, took a job as a meatpacker and moved the family to Omaha. Vinovskis shares, “The continued economic challenges facing our family aroused my early interest in public policy, especially on how to help low-income families.”

Excellence in academics and athletics led to his admission to Wesleyan University with a National Merit Scholarship. Vinovskis ultimately pursued a degree in History, with an interest in Public Policy but no clear career direction. In 1965, he hitchhiked to Alabama to participate in the March on Selma, but was arrested en route in Montgomery at a peaceful NAACP demonstration. After a week of hunger striking in jail, he was bailed out. Vinovskis views this event as seminal, focusing his ambition on fostering social justice and helping the disadvantaged.

Vinovskis moved on to complete a Ph.D. in History at Harvard University. He and his wife Mary chose to forgo upscale Cambridge living in favor of working class Somerville, where he joined the NAACP and the Somerville Racial Understanding Committee, and started working for the newly elected mayor – his first official government position. In writing his dissertation on the late eighteenth-century and antebellum decrease in Massachusetts birth rates, Vinovskis encountered the issue of education. He uncovered a significant decline in preschool enrolment between 1840 and 1860, corresponding to a popularized belief that early cognitive stimulation led to insanity!

After a faculty position at the University of Wisconsin Madison, Vinovskis joined the History Department and Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. Here, he has pursued research in education history, demographic and family history, antebellum insane asylums, and federal abortion funding. He has also served as the Deputy Staff Director to the U.S. House Select Committee on Population in 1978 and was a consultant on population and adolescent pregnancy issues in the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare in the early 1980s. He worked in the U.S. Department of Education in both the George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton administrations on questions of educational research and policy. He also testified before six House and Senate committees about education and served on independent review panels for Goals 2000 and No Child Left Behind.

Vinovskis has published ten books, edited seven books, and written over 100 scholarly essays. He received a Guggenheim fellowship and was elected to the National Academy of Education, the International Academy of Education, a fellow to the American Educational Research Association, and President of the History of Education Society.

As Vinovskis says, “Education always played a very important role in my life.” The very education that propelled him from an immigrant life in rural Nebraska to elite student status became the focus of his academic research and government service.

Aug 22, 2013 | Innovative Methodology, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Nicholas Valentino

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Since the attacks of September 11, 2001, airport security has become a grave and expensive endeavor, projected to cost $45 billion by 2018. News stories about airport security scares or the ridiculousness of airport security scares proliferate. Other stories concern the efficacy of racial profiling, particularly of Arab passengers. A new Transportation Security Administration (TSA) program called SPOT – Screening of Passengers by Observation Technique – targets suspicious behavior in security lines with in-depth questioning. This program alone has cost $878 million. And SPOT faces criticisms for propagating racial profiling.

Forthcoming research by Center for Political Studies researcher Nicholas Valentino, along with colleagues Cigdem Sirin and Jose Villalobos from the University of Texas El Paso, explore the factors that explain support for racial profiling. In particular these scholars wondered whether different racial groups, with their different experiences with discrimination, react distinctly to security policies that involve profiling.

Valentino and colleagues investigated this question in an experiment. The sample focused on three racial groups and included 221 whites, 193 blacks, and 207 Latinos. All participants read a vignette:

Recently, a passenger was flying from New York to Chicago when he was pulled out of a security line, searched, and questioned. The passenger was talking on his cell phone while waiting in line to board his flight. One of the airport security officers standing nearby said that he heard the passenger say, “It’s a go!” which qualifies as suspicious behavior according to the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) guidelines. In response, the airport security officer took the passenger aside for further screening. The passenger, however, claims that when it was his turn to board the plane, he had told the person on the phone, “I’ve got to go!” and hung up. Amid the controversy, the airport security officer said that he had a reasonable cause to search and question the passenger. The passenger, on the other hand, said that the additional screening was unwarranted.

The picture presented alongside the text varied, with participants randomized to see a suspect from one of four racial groups: black, white, Latino, or Arab. Pictures were pretested to ensure equality on all dimensions except ethnic identity. After reading the story, participants answered several questions, including, “Who are you more likely to agree with in this case—the airport security officer or the passenger?” and “What do you think about the response by the airport security officer—do you think he had a reasonable cause to search and question the passenger?”

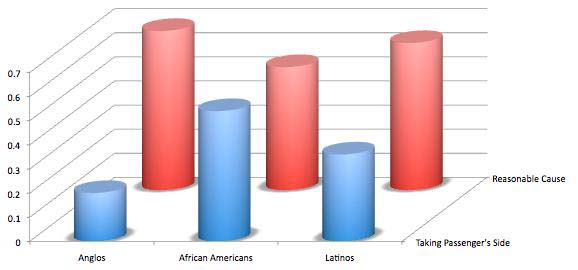

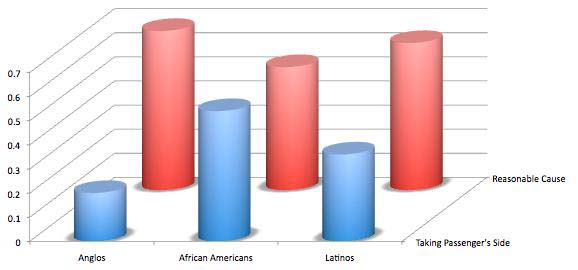

The graph below displays the results for the Arab passenger scenario. Compared to whites, blacks and Latinos showed less support for extra airport security measures targeting an Arab passenger. Further, the likelihood of siding with the Arab passenger is about 36 percent higher for black respondents and about 26 percent higher for Latino respondents.

Yet, blacks and Latinos perceive themselves to be at higher risk of personal threat from terrorism. Valentino and colleagues suggest this pattern is consistent with Group Empathy Theory, which holds that empathy for one group by another, even when the two are in competition for the same resources, mitigates support for harsh security tactics.

Lawmakers and TSA programs should keep in mind, as Valentino states, “These results demonstrate that anti-Arab sentiment is not distributed uniformly throughout society, and support our theory that the power of existential threats on tolerance is moderated by group empathy.”

Aug 16, 2013 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International, National

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Darrell Donakowski

Yesterday, The Washington Post released an internal report from the National Security Agency (NSA) revealing the agency broke its own privacy rules thousands of times per year since 2008. The source? Edward Snowden, former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) employee and analyst at NSA contractor Booz Allen. The Post release is the latest chapter in the story of Snowden and government trust.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In June and July of this year, UK’s The Guardian published a series of news articles revealing surveillance by NSA. The US charged Snowden with espionage and revoked his passport. On the lamb, Snowden flew to Hong Kong from Hawai’i. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange worked to broker asylum for Snowden in Iceland to no avail. Snowden moved onto Russia, residing in the transit zone of Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport for over a month. On August 1, Russia granted Snowden a one-year asylum. Snowden has an additional 20 applications out for asylum.

Snowden’s asylum prospects complicate US international relations. Obama canceled a summit with Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. Senator Lindsey Graham (R) called for a boycott of the 2014 Olympics in Sochi, Russia, a plan rejected by Speaker of the House John Boehner. On July 2, Bolivian President Evo Morales’ plane was denied entry to several European nations’ airspace and airports amid rumors Snowden was on board, stressing European and US relations with several Latin American countries (Bolivia, Venezuela, and Nicaragua granted Snowden’s request for asylum).

In the wake of the story, questions turned into a debate in the media as to how to understand Snowden. Leaker? Traitor? Punk? The American public appears to see Snowden as a whistleblower. Further, the media linked the immediate fallout – plus the IRS scandal and Benghazi trials – with an 8 point drop in Obama’s approval rating. Hovering around 44%, Gallup shows Obama’s recent ratings below the presidential average of 54%.

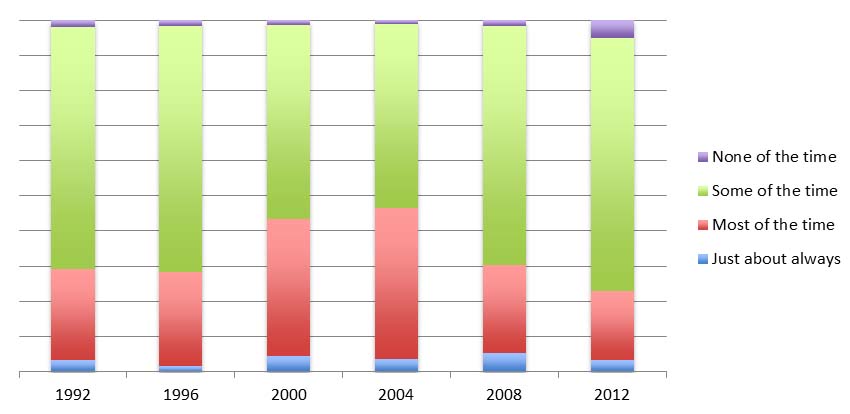

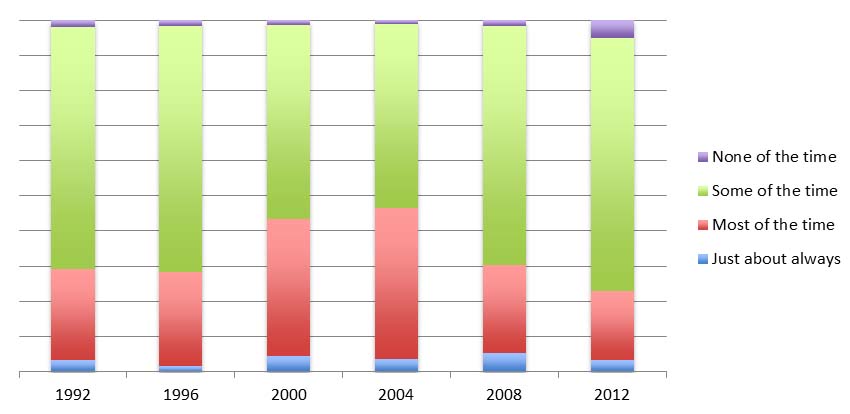

But what about trust in the government in particular? The American National Election Studies offers a glimpse of trust in government across time. Asked how much of the time the government does what is right, respondents could choose between three answers: “just about always,” “most of the time,” and “some of the time,” with some respondents volunteering “none of the time.” The graph below displays the spread across time and across answers.

How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Washington to do what is right?

While this graph does not correspond to the Snowden event, it contextualizes the attributed decrease in trust across time. That is, the decrease in trust attributed to the leak would correspond to a generally decreasing trend.

Last week, Obama announced an overhaul of NSA surveillance. Though Obama refuses to acknowledge Snowden as a catalyst for the changes, Assange claims the move vindicates Snowden. The move suggests a push for transparency and restored trust in the government.

Aug 13, 2013 | Michigan, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Rosemary Sarri

Detroit makes headlines often: declining population, high crime rates, blocks of urban blight and, recently, the city’s declaration of bankruptcy. How does living in this bad news impact the city’s children? And, perhaps more importantly, how are we coping with the inevitable fallout this has on Detroit’s children?

Detroit makes headlines often: declining population, high crime rates, blocks of urban blight and, recently, the city’s declaration of bankruptcy. How does living in this bad news impact the city’s children? And, perhaps more importantly, how are we coping with the inevitable fallout this has on Detroit’s children?

Center for Political Studies, School of Social Work, and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri studies the impact of social policy on children. In a forthcoming book chapter – “Juvenile Justice in a Changing Environment” – Sarri considers the developing approaches to juvenile offenders, focusing on Wayne County, Michigan, home of Detroit.

The concept of approaching juveniles in the justice system as distinct from their adult counterparts emerged just over a century ago. Two Supreme Court decisions – Roper v. Simmons in 1995 and Graham v. Florida in 2010 – reasserted the necessity of lesser sentences for youth offenders. Further, there is a large capital investment in the system. With 70,000 children in the justice system at an individual incarceration cost of $88,000 per year, the total exceeds $6 billion annually. This large amount of money coupled with the increasing emphasis on viewing children as in the midst of development shifted focus to rehabilitation over punishment. Wayne County, including Detroit, has paved the way.

In the 1990s, the state of Michigan controlled Wayne County’s youth offenders, punishing both serious and lesser crimes with long periods of detention, often out of state. U.S. Department of Justice threatened to close the in-county detention facility itself due to overcrowding and poor physical conditions, while the Michigan Auditor General issued a report criticizing the whole process. Without adequate mental health services and educational aid, recidivism – committing crimes again upon being released – topped 50%. The county and state spent $150 million per year on this ineffective program.

In the late 1990s, crime overall declined, but youth crimes associated with Detroit’s problems of homelessness, substance abuse, and gangs continued. Public outcry and political pressure to revamp the juvenile justice system was answered in 1997, when the system was overhauled.

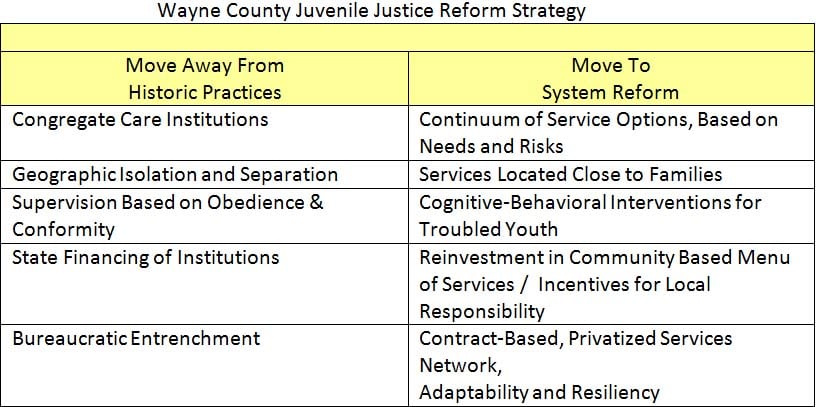

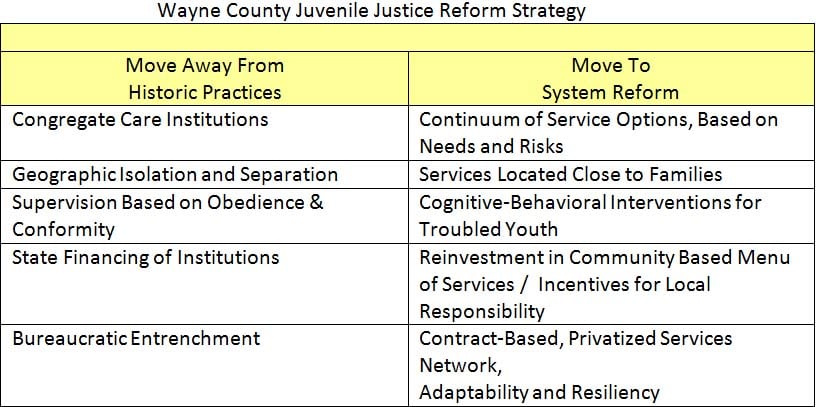

The new mission, as Sarri writes, was to, “Treat each individual as a person in need of opportunities and resources rather than one with a societal disease that needed to be contained.” Wayne County spearheaded the initiative, which emphasized mental health care, education, and alternatives to incarceration, as summarized by the table below

The information management also built into the new approach allows the effects to be quantified. In 1998, 731 youth were incarcerated. In 2012, there were six, with no juveniles placed out of state. From 2004 to 2012, the number of new delinquency cases dropped by 38.4%. Further, more children have access to diversion and prevention programs, totaling 9,319 in 2012. And recidivism dropped to 17.5%!

As Detroit’s woes deepen, the toll on Wayne County’s children will likely increase. But, as Sarri argues, the juvenile justice system initiated in the late 1990s is an investment in the community, rehabilitating youth instead of punishing them for their declining environment.