Sep 26, 2019 | Current Events, Elections, Innovative Methodology, National

Post developed by Katherine Pearson

How much does partisanship explain how legislative districts are drawn? Legislators commonly agree on neutral criteria for drawing district lines, but the extent to which partisan considerations overshadow these neutral criteria is often the subject of intense controversy.

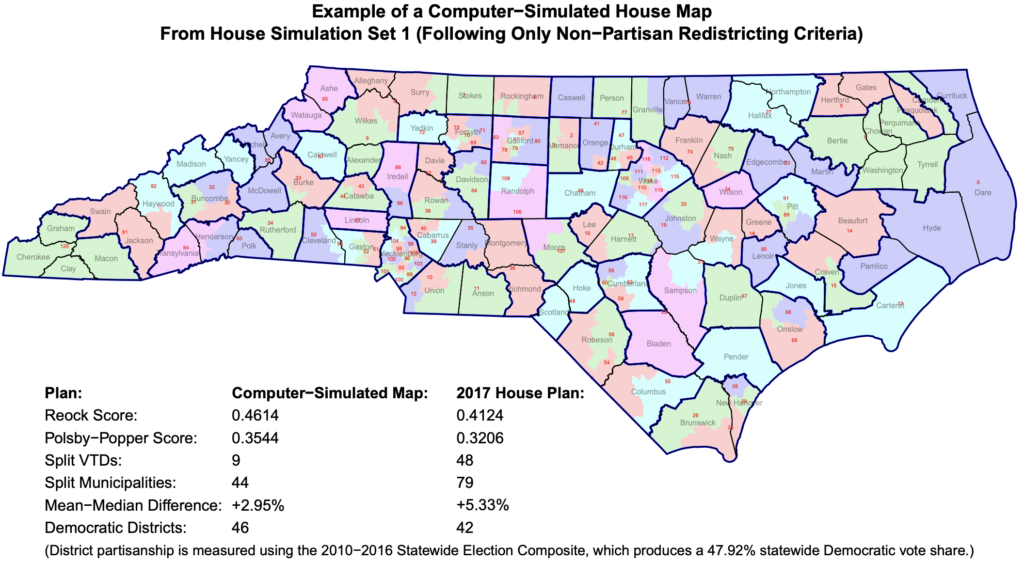

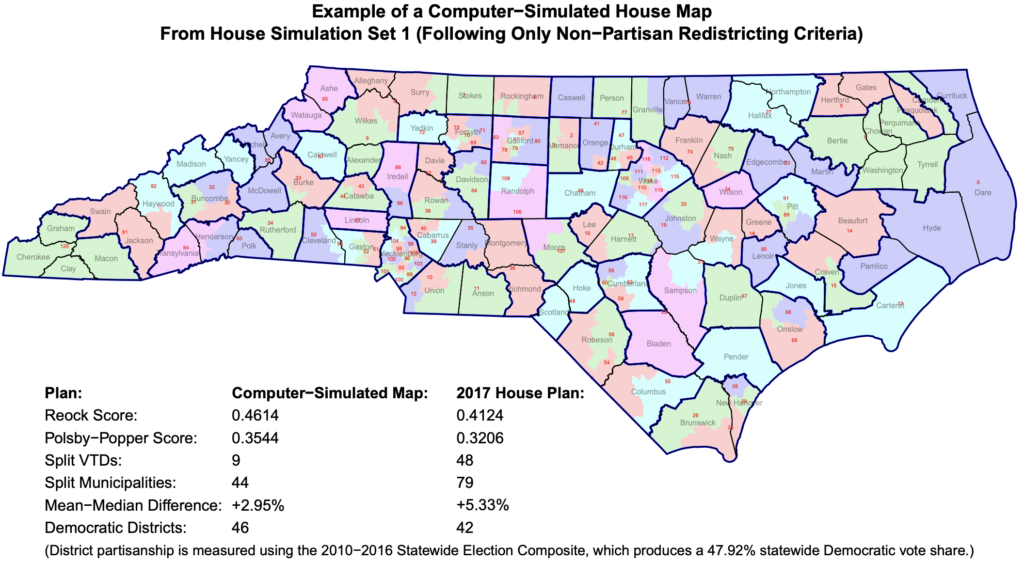

Jowei Chen developed a new way to analyze legislative districts and determine whether they have been unfairly gerrymandered for partisan reasons. Chen, an Associate Professor of Political Science and a Research Associate at the Center for Political Studies, used computer simulations to produce thousands of non-partisan districting plans that follow traditional districting criteria.

These simulated district maps formed the basis of Chen’s recent expert court testimony in Common Cause v. Lewis, a case in which plaintiffs argued that North Carolina state legislative district maps drawn in 2017 were unconstitutionally gerrymandered. By comparing the non-partisan simulated maps to the existing districts, Chen was able to show that the 2017 districts “cannot be explained by North Carolina’s political geography.”

The simulated maps ignored all partisan and racial considerations. North Carolina’s General Assembly adopted several traditional districting criteria for drawing districts, and Chen’s simulations followed only these neutral criteria, including: equalizing population, maximizing geographic compactness, and preserving political subdivisions such as county, municipal, and precinct boundaries. By holding constant all of these traditional redistricting criteria, Chen determined that the 2017 district maps could not be explained by factors other than the intentional pursuit of partisan advantage.

Specifically, when compared to the simulated maps, Chen found that the 2017 districts split far more precincts and municipalities than was reasonably necessary, and were significantly less geographically compact than the simulations.

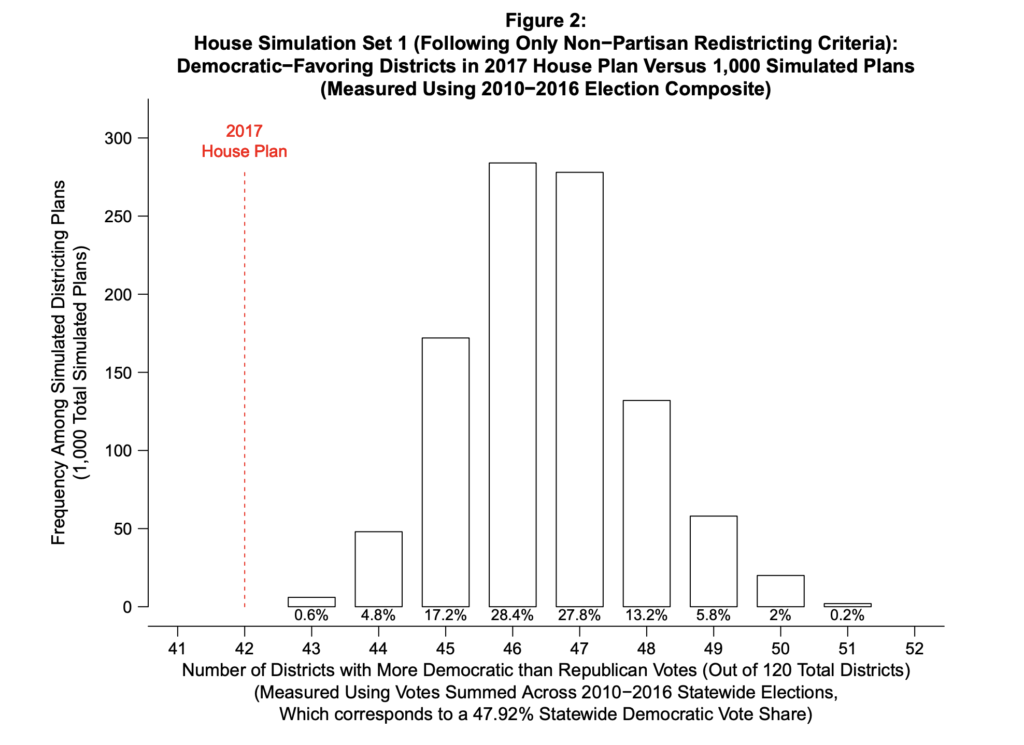

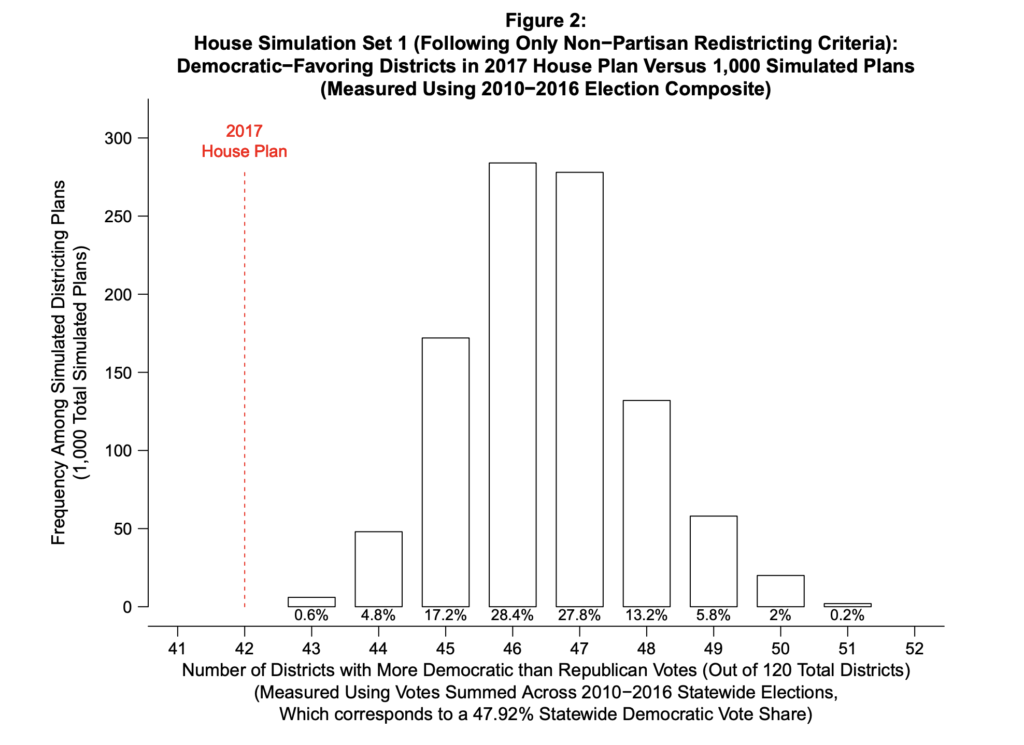

By disregarding these traditional standards, the 2017 House Plan was able to create 78 Republican-leaning districts out of 120 total; the Senate Plan created 32 Republican-leaning districts out of 50.

Using data from 10 recent elections in North Carolina, Chen compared the partisan leanings of the simulated districts to the actual ones. Every one of the simulated maps based on traditional criteria created fewer Republican-leaning districts. In fact, the 2017 House and Senate plans were extreme statistical outliers, demonstrating that partisanship predominated over the traditional criteria in those plans.

The judges agreed with Chen’s analysis that the 2017 maps displayed Republican bias, compared to the maps he generated by computer that left out partisan and racial considerations. On September 3, 2019, the state court struck down the maps as unconstitutional and enjoined their use in future elections.

The North Carolina General Assembly rushed to adopt new district maps by the court’s deadline of September 19, 2019. To simplify the process, legislators agreed to use Chen’s computer-simulated maps as a starting point for the new districts. The legislature even selected randomly from among Chen’s simulated maps in an effort to avoid possible accusations of political bias in its new redistricting process.

Determining whether legislative maps are fair will be an ongoing process involving courts and voters across different states. But in recent years, the simulation techniques developed by Chen have been repeatedly cited and relied upon by state and federal courts in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and elsewhere as a more scientific method for measuring how much districting maps are gerrymandered for partisan gain.

Sep 6, 2019 | APSA, Current Events, National, Policy, Race, Social Policy

Post developed by Nicholas Valentino, Ali Valenzuela, Omar Wasow, and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Rousing the Sleeping Giant? Emotions and Latino Mobilization in an Anti-Immigration Era” was a part of the session “The Rhetoric of Race” on Friday, August 30, 2019.

Since the 2016 presidential campaign anti-immigration policies have been very popular among President Trump’s strongest supporters, though they do not present obvious benefits to the economy or national security. Strategists suppose that the intent of the anti-immigration rhetoric and policies is to energize the president’s base.

But what about people who identify with the targets of these policies, specifically Latinos? Are they mobilized against anti-immigration proposals, or are they further deterred from political participation?

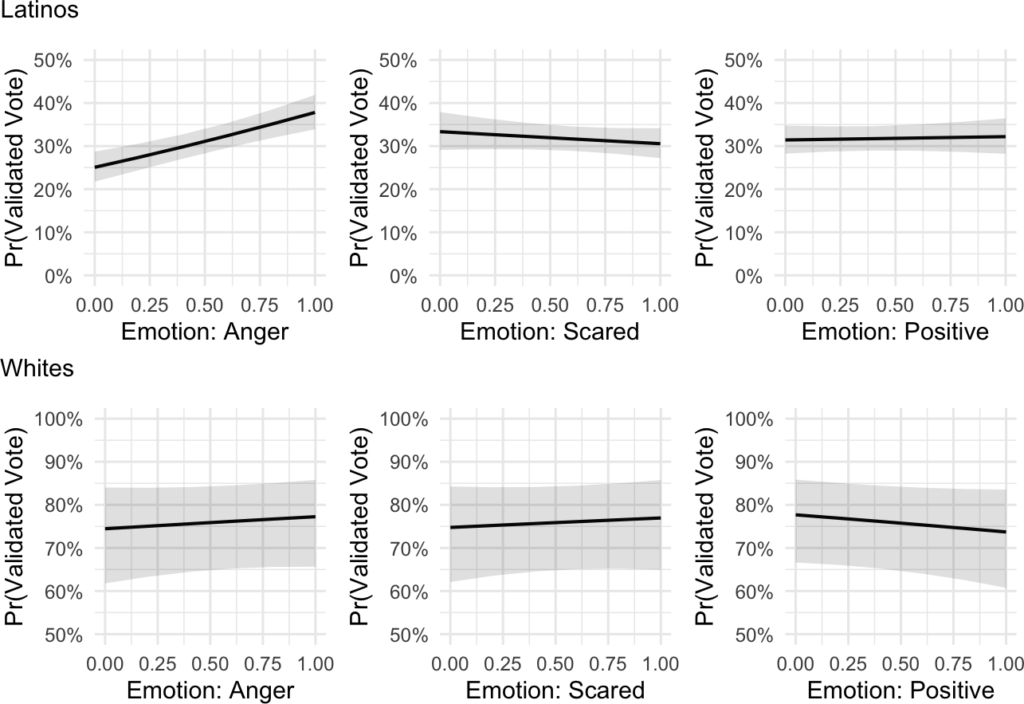

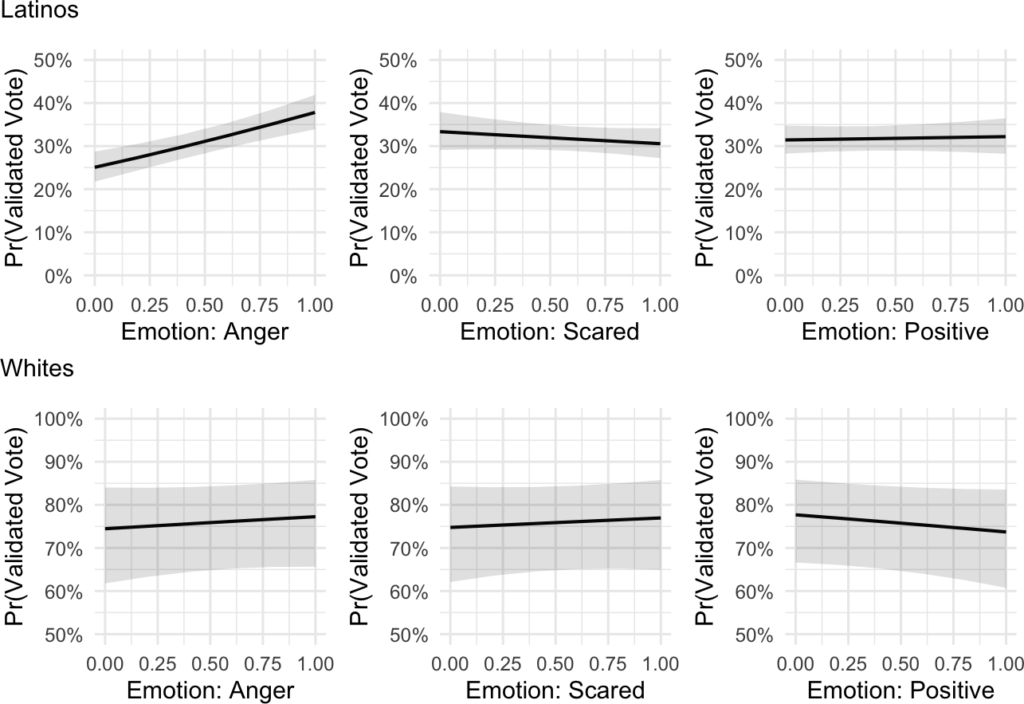

New research by Nicholas A. Valentino, Ali Valenzuela, and Omar Wasow finds that anger was associated with higher voter turnout among Latinos, but the Latinos who expressed more fear had lower voting rates.

The role of emotions in politics is complex. The research team begins with the observation that negative emotions do not always have negative consequences for politics. Indeed, negative emotions may promote attention and interest, and drive people to vote. They draw a distinction between different negative emotions: while anger may spur political action, fear can suppress it.

The research team fielded a nationally-representative panel survey of white and Latino registered voters before and after the 2018 midterm elections. Respondents were asked about their experience with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials and their exposure to campaign ads focused on immigration. Participants were also asked to rate their emotional reactions to the current direction of the country.

The results showed that Latinos interacted with ICE more frequently than whites did, but both groups had the same level of exposure to campaign ads. Latinos reported more anger than whites, and also more fear. In fact, among the negative emotions in the survey, fear among Latinos was highest.

In the sample the validated voting rate among Latinos was 39%; among whites in the sample it was 72%, demonstrating the under-mobilization of Latino voters. Whether Latinos vote in greater numbers in 2020 may depend on whether they are mobilized by anger against anti-immigration rhetoric, or whether they are deterred by fear stemming from policies like ICE detention and deportation.

Sep 3, 2019 | APSA, Innovative Methodology, Policy

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Stuart Soroka

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Media (In)accuracy on Public Policy, 1980-2018” was a part of the session “Truth and/or Consequences” on Sunday, September 1, 2019.

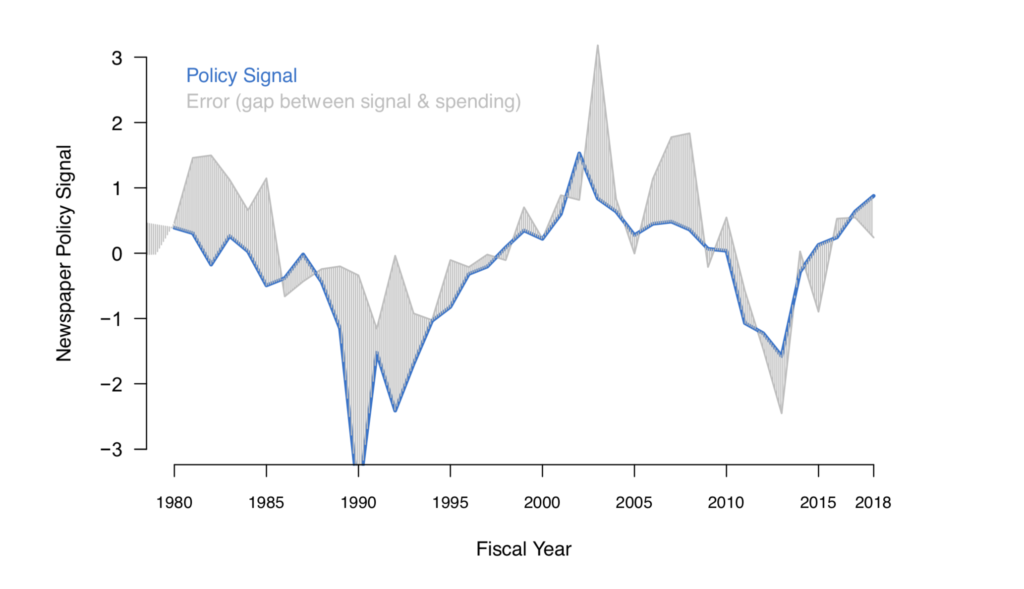

Citizens can be well-informed about public policy only if the media accurately present information on the issues. Today’s media environment is faced with valid concerns about misinformation and biased reporting, but inaccurate reporting is nothing new. In their latest paper, Stuart Soroka and Christopher Wlezien analyze historical data on media coverage of defense spending to measure the accuracy of the reporting when compared to actual spending.

In order to measure reporting on defense spending, Soroka and Wlezien compiled text of media reports between 1980 and 2018 from three corpuses: newspapers, television transcripts, and public affairs-focused Facebook posts. Using the Lexis-Nexis Web Services Kit, they developed a database of sentences focused on defense spending from the 17 newspapers with the highest circulation in the United States. Similar data were compiled with transcripts from the three major television broadcasters (ABC, CBS, NBC) and cable news networks (CNN, MSNBC, and Fox). Although more difficult to gather, data from the 500 top public affairs-oriented public pages on Facebook were compiled from the years 2010 through 2017.

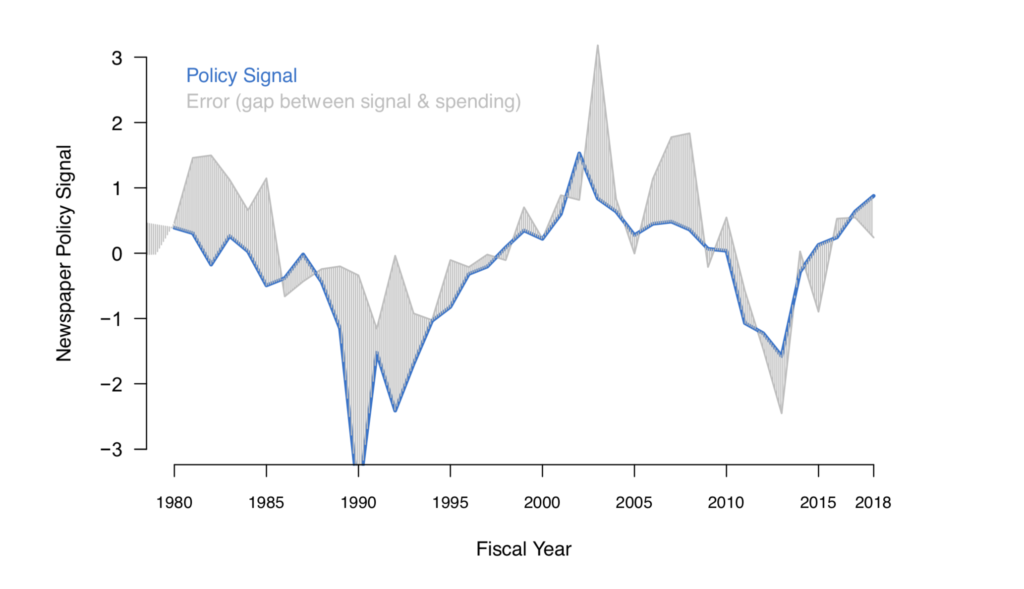

Soroka and Wlezien estimated the policy signal conveyed by the media sources by measuring the extent to which the text suggests that defense spending has increased, decreased, or stayed the same. Comparing this directly to actual defense spending over the same time period reveals the accuracy of year-to-year changes in the media coverage. For example, if media coverage were perfectly accurate, the signal would be exactly the same as actual changes in spending.

As the figure below shows, the signal is not perfect. While there are some years when the media coverage tracks very closely to actual spending, there are other years when there is a large gap between the signal that news reports send and the defense budget. The gap may not entirely represent misinformation, however. In some of these cases, the media may be reporting on anticipated future changes in spending.

For most years, the gap representing misinformation is fairly small. Soroka and Wlezien note that this “serves as a warning against taking too seriously arguments focused entirely on the failure of mass media.” This analysis shows evidence that media coverage can inform citizens about policy change.

The authors conclude that there are both optimistic and pessimistic interpretations of the results of this study. On one hand, for all of the contemporary concerns about fake news, it is still possible to get an accurate sense of changes in defense spending from the media, which is good news for democratic citizenship. However, they observed a wide variation in accuracy among individual news outlets, which is a cause for concern. Since long before the rise of social media, citizens have been at risk of consuming misinformation based on the sources they select.

Sep 1, 2019 | APSA, Current Events, International

Post developed by Pauline Jones, Anil Menon, and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Putin’s Pivot to Populism” was a part of the session “Russia and Populism” on Sunday, September 1, 2019.

The rise in populism around the world has received much attention, but not all populists are the same. In a new paper, Pauline Jones and Anil Menon present an original typology of populists that goes beyond typical left-wing versus right-wing classifications.

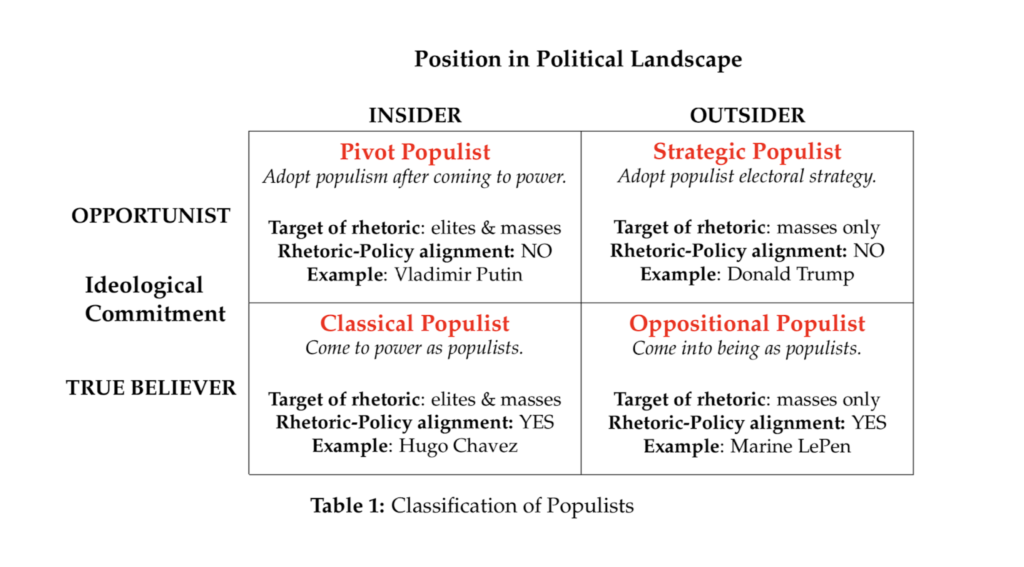

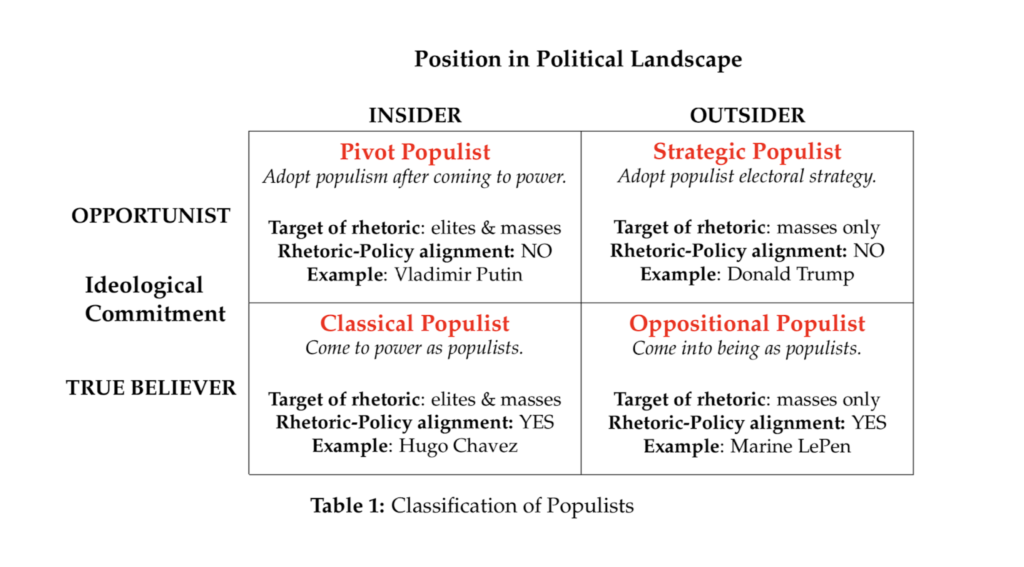

To better understand the different types of populists and how they operate, Jones and Menon examine two key dimensions: position within the political landscape (outsider versus insider), and level of ideological commitment (true believer versus opportunist).

Populists tend to frame their criticism of political elites differently depending on whether they are political outsiders or government insiders. While outsiders are free to criticize those in power broadly, populists who hold political power are more likely to tailor their criticisms to their political opponents. Insiders are also more careful not to attack members of the elite with whom they will need to build political coalitions.

Many populists evoke the past, but outsiders and insiders tend to do so differently. Whereas outsiders focus on the near past as a critique of a corrupt elite, political insiders instead focus on the distant past to evoke better days of shared national values.

Jones and Menon also draw distinctions between true believers in populism and those who embrace populism for purely strategic reasons. True believers will remain strongly committed to enacting their populist agenda once in office; opportunists will use populist rhetoric to gain power, but won’t support their platform strongly if elected.

The intersection of these two dimensions leads to the classification of populists into four types, illustrated in the table below: Oppositional, Classical, Strategic, and Pivot.

The most common variety of populist is the oppositional populist, who are outsiders and true believers. Oppositional populists put their agenda before all else and distance themselves from the mainstream elite.

Classical populists sometimes start out as outsiders who become insiders once they are elected to office. Like oppositional populists, they are strongly committed to enacting their agenda; unlike oppositional populists, classical populists can enact their agenda from a position of power. Because they are insiders, classical populists are more selective about criticizing elites.

Pivot populists are a rare group of political insiders who adopt populist rhetoric with little or no commitment to the populist ideology. Jones and Menon point to Russia’s Vladimir Putin as an example of a pivot populist who has adopted populism to bolster support for his regime while deflecting blame for the country’s problems.

The final category is strategic populists. Like Donald Trump in the United States, strategic populists are outsiders with a weak commitment to the populist agenda. Strategic populists are broadly anti-elite, and also use their rhetoric to create divisions among the people. Once in power, they are unlikely to alienate elites by pursuing populist policy goals.