Sep 15, 2020 | APSA, Elections, International

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Electoral Volatility in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes” was a part of the session “Elections Under Autocracy” on Sunday, September 13, 2020.

Until recently, there has been little need to measure the electoral volatility, changes in vote shares between parties, in authoritarian regimes because most conventional authoritarian regimes were either one-party or no-party systems. In general, high levels of volatility are considered to be a sign of instability in the party system and show that the existing parties are unable to build connections with their constituencies.

New research by Wooseok Kim, Allen Hicken, and Michael Bernhard examines the ways that electoral volatility in democratic regimes may be useful for understanding competitive authoritarian regimes.

As a greater number of authoritarian regimes have permitted electoral competition and greater party autonomy, electoral volatility has become more salient. Multiparty elections in competitive authoritarian regimes are different from those in democracies, in that competition is more constrained and incumbents have the ability to manipulate the outcomes.

Electoral volatility can provide clues about the level institutionalization in the ruling and opposition parties, as well as the level of support for the authoritarian incumbent. Low volatility suggests a high level of stability and control in the ruling party institutionalization; high volatility as associated with weak party organizations, weak societal roots, and low levels of cohesion.

The authors tested the relationship between electoral volatility, which is the most commonly used measure of party system institutionalization, and the survival of competitive authoritarian regimes. To do this, they used a dataset that included authoritarian regimes in the post-WWII period that hold minimally competitive multiparty elections with basic suffrage, which are determined using indicators from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem).

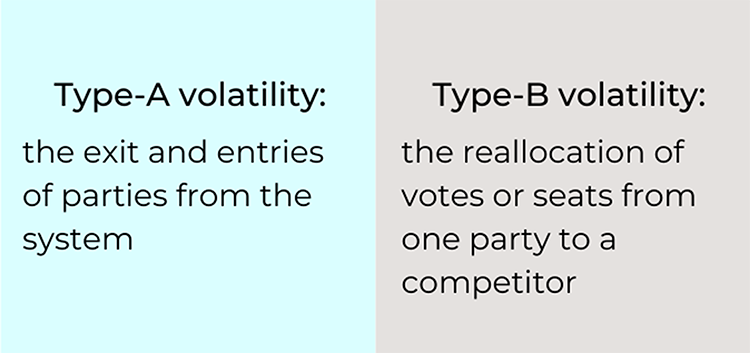

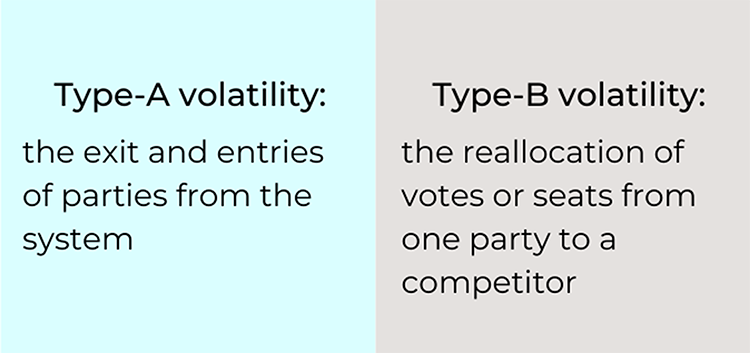

Specifically, the authors measure two types of electoral volatility in competitive authoritarian regimes: type-A volatility and type-B volatility. Type-A is volatility measures the exit and entries of parties from the system. Type-B volatility measures the reallocation of votes or seats from one party to a competitor.

Electoral authoritarian regimes are more stable when they tightly control the party system and the opposition is disorganized. The authors conclude that type-B volatility promotes authoritarian replacement, while type-A volatility is associated with a greater likelihood of a democratic transition. In addition to considering measures of party system institutionalization in authoritarian regimes, future case studies may shed more light on the link between electoral dynamics and outcomes.

Sep 14, 2020 | APSA

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Local Economic Malaise and the Rise of Anti-Everything Extremism” was a part of the session “Extreme Parties and Positions” on Saturday, September 12, 2020. Post developed by Hayden Jackson and Katherine Pearson.

Is it economic downturns or threats to cultural identity that lead some individuals to respond to populist and extreme-nationalist appeals? These explanations complement, rather than compete with one another, according to new research by Diogo Ferrari, Rob Franzese, Hayden Jackson, ByungKoo Kim, Wooseok Kim, and Patrick Wu.

Some people experiencing a decline in standard of living may react by supporting populist movements, including those that place blame for economic and social deterioration on out-groups. While economic downturns can spur support for nationalism, these factors are also deeply entwined with feelings of being left behind in a social and cultural context. This is especially true in hard-hit rural communities that feel neglected and misunderstood by policy makers and elites.

Whereas previous literature presents economic malaise and cultural or status threat as competing explanations for the rise of populist attitudes, the authors of this paper argue that these effects are not competing, but complementary. When the community experiences economic decline, some individuals will feel that their identity is under threat, and that they are looked down upon by elites. The feeling that their way of life is under attack leaves some individuals susceptible to extremist appeals. However, these appeals do not work on all members of the community equally; important differences may be explained by life experiences, education, personal income, and demographics, especially race.

One’s views and behaviors grow as a result of complex economic and cultural experiences. Some people will have experiences or personalities that predispose them to respond differently to economic and social shocks. For some, economic decline may trigger xenophobic, anti-elite reactions that will not be experienced by all members of the community.

To test the relationship between economic malaise and the perception of social threat, the authors conducted two empirical explorations. The first study reanalyzed data from Mutz 2018 to identify the effects of features like neighborhood decline or individual characteristics in subgroups with different responses to economic decline.

A second study focuses on structural differences that appear in data from Twitter data before and after automotive plant shutdowns in southeast Michigan and northeast Ohio. Data suggests that neighborhood economic shocks, like the closing of a factory, triggered rising extremist expression in at least some contexts. The increase in extremist-engaging Tweet activity was largest in the community around Lordstown, Ohio, which is predominantly white and rural/exurban. By comparison, the data showed slightly negative trends in extremist Tweets in the predominantly Black, urban community around Hamtramck, Michigan, which was also hit by a plant closing.

The authors hypothesize that the response to an economic shock, such as a plant closing, is likely to depend on the size of the closure “shock”, or how much impact it has and on the community, as well as the social and demographic characteristics of the local workers, particularly the community’s urban or rural nature and the racial makeup. In the analysis, these factors were most relevant when determining an extremist-engagement response. The bigger the economic shock to the community, and the more white and rural the community, the more likely it is to see an extreme response.

Sep 11, 2020 | APSA, Innovative Methodology

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Joint Image-Text Classification Using an Attention-Based LSTM Architecture” was a part of the session “Image Processing for Political Research” on Thursday, September 10, 2020. Post developed by Patrick Wu and Katherine Pearson.

Political science has been enriched by the use of social media data. However, automated text-based classification systems often do not capture image content. Since images provide rich context and information in many tweets, these classifiers do not capture the full meaning of the tweet. In a new paper presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA), Patrick Wu, Alejandro Pineda, and Walter Mebane propose a new approach for analyzing Twitter data using a joint image-text classifier.

Human coders of social media data are able to observe both the text of a tweet and an attached image to determine the full meaning of an election incident being described. For example, the authors show the image and tweet below.

If only the text is considered, “Early voting lines in Palm Beach County, Florida #iReport #vote #Florida @CNN”, a reader would not be able to tell that the line was long. Conversely, if the image is considered separately from the text, the viewer would not know that it pictured a polling place. It’s only when the text and image are combined that the message becomes clear.

MARMOT

A new framework called Multimodal Representations Using Modality Translation (MARMOT) is designed to improve data labeling for research on social media content. MARMOT uses modality translation to generate captions of the images in the data, then uses a model to learn the patterns between the text features, the image caption features, and the image features. This is an important methodological contribution because modality translation replaces more resource-intensive processes and allows the model to learn directly from the data, rather than on a separate dataset. MARMOT is also able to process observations that are missing either images or text.

Applications

MARMOT was applied to two datasets. The first dataset contained tweets reporting election incidents during the 2016 U.S. general election, originally published in “Observing Election Incidents in the United States via Twitter: Does Who Observes Matter?” The tweets in this dataset report some kind of election incident. All of the tweets contain text, and about a third of them contain images. MARMOT performed better at classifying the tweets than the text-only classifier used in the original study.

In order to test MARMOT against a dataset containing images for every observation, the authors used the Hateful Memes dataset released by Facebook to assess whether a meme is hateful or not. In this case, a multimodal model is useful because it is possible for neither the text nor the image to be hateful, but the combination of the two may create a hateful message. In this application, MARMOT outperformed other multimodal classifiers in terms of accuracy.

Future Directions

As more and more political scientists use data from social media in their research, classifiers will have to become more sophisticated to capture all of the nuance and meaning that can be packed into small parcels of text and images. The authors plan to continue refining MARMOT, and expand the models to accommodate additional elements such as video, geographical information, and time of posting.

Sep 6, 2019 | APSA, Current Events, National, Policy, Race, Social Policy

Post developed by Nicholas Valentino, Ali Valenzuela, Omar Wasow, and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Rousing the Sleeping Giant? Emotions and Latino Mobilization in an Anti-Immigration Era” was a part of the session “The Rhetoric of Race” on Friday, August 30, 2019.

Since the 2016 presidential campaign anti-immigration policies have been very popular among President Trump’s strongest supporters, though they do not present obvious benefits to the economy or national security. Strategists suppose that the intent of the anti-immigration rhetoric and policies is to energize the president’s base.

But what about people who identify with the targets of these policies, specifically Latinos? Are they mobilized against anti-immigration proposals, or are they further deterred from political participation?

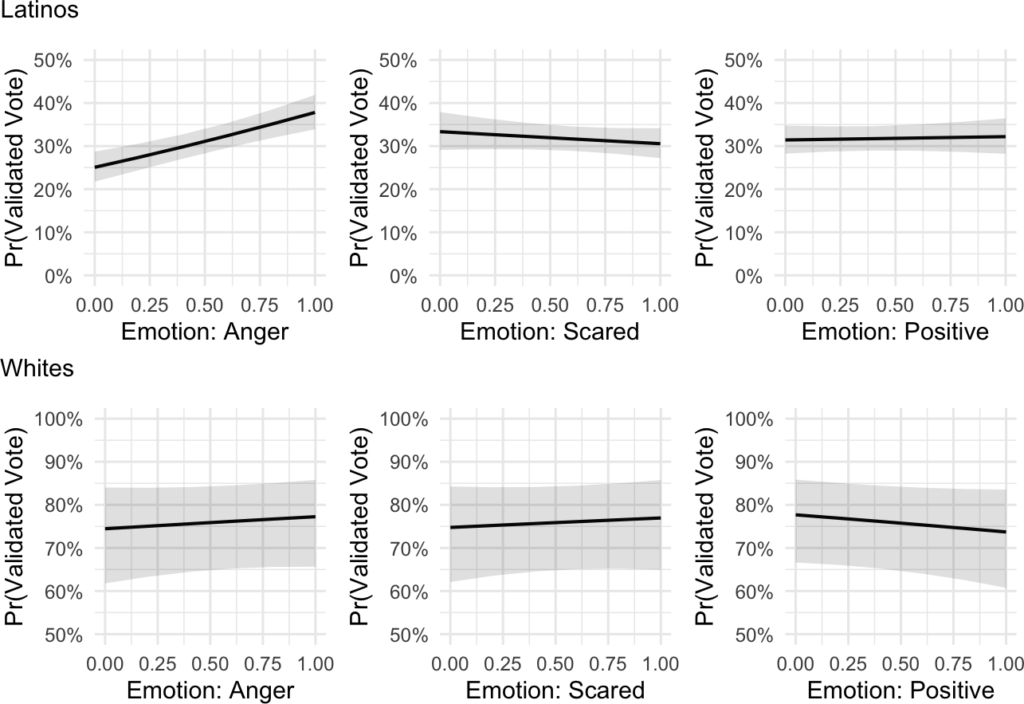

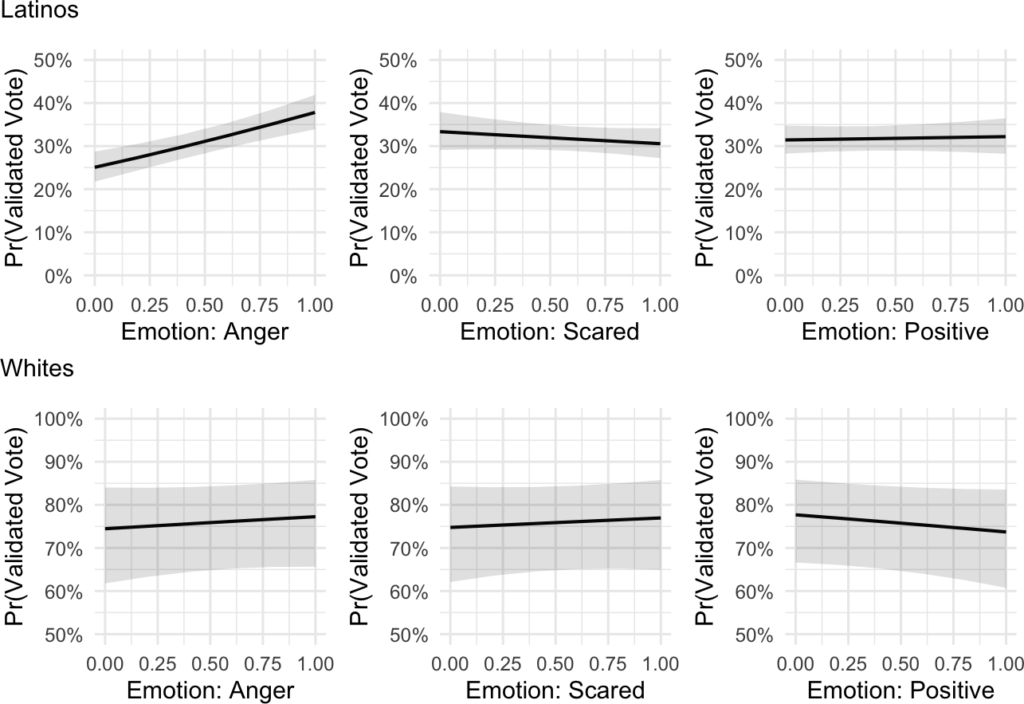

New research by Nicholas A. Valentino, Ali Valenzuela, and Omar Wasow finds that anger was associated with higher voter turnout among Latinos, but the Latinos who expressed more fear had lower voting rates.

The role of emotions in politics is complex. The research team begins with the observation that negative emotions do not always have negative consequences for politics. Indeed, negative emotions may promote attention and interest, and drive people to vote. They draw a distinction between different negative emotions: while anger may spur political action, fear can suppress it.

The research team fielded a nationally-representative panel survey of white and Latino registered voters before and after the 2018 midterm elections. Respondents were asked about their experience with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials and their exposure to campaign ads focused on immigration. Participants were also asked to rate their emotional reactions to the current direction of the country.

The results showed that Latinos interacted with ICE more frequently than whites did, but both groups had the same level of exposure to campaign ads. Latinos reported more anger than whites, and also more fear. In fact, among the negative emotions in the survey, fear among Latinos was highest.

In the sample the validated voting rate among Latinos was 39%; among whites in the sample it was 72%, demonstrating the under-mobilization of Latino voters. Whether Latinos vote in greater numbers in 2020 may depend on whether they are mobilized by anger against anti-immigration rhetoric, or whether they are deterred by fear stemming from policies like ICE detention and deportation.

Sep 3, 2019 | APSA, Innovative Methodology, Policy

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Stuart Soroka

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Media (In)accuracy on Public Policy, 1980-2018” was a part of the session “Truth and/or Consequences” on Sunday, September 1, 2019.

Citizens can be well-informed about public policy only if the media accurately present information on the issues. Today’s media environment is faced with valid concerns about misinformation and biased reporting, but inaccurate reporting is nothing new. In their latest paper, Stuart Soroka and Christopher Wlezien analyze historical data on media coverage of defense spending to measure the accuracy of the reporting when compared to actual spending.

In order to measure reporting on defense spending, Soroka and Wlezien compiled text of media reports between 1980 and 2018 from three corpuses: newspapers, television transcripts, and public affairs-focused Facebook posts. Using the Lexis-Nexis Web Services Kit, they developed a database of sentences focused on defense spending from the 17 newspapers with the highest circulation in the United States. Similar data were compiled with transcripts from the three major television broadcasters (ABC, CBS, NBC) and cable news networks (CNN, MSNBC, and Fox). Although more difficult to gather, data from the 500 top public affairs-oriented public pages on Facebook were compiled from the years 2010 through 2017.

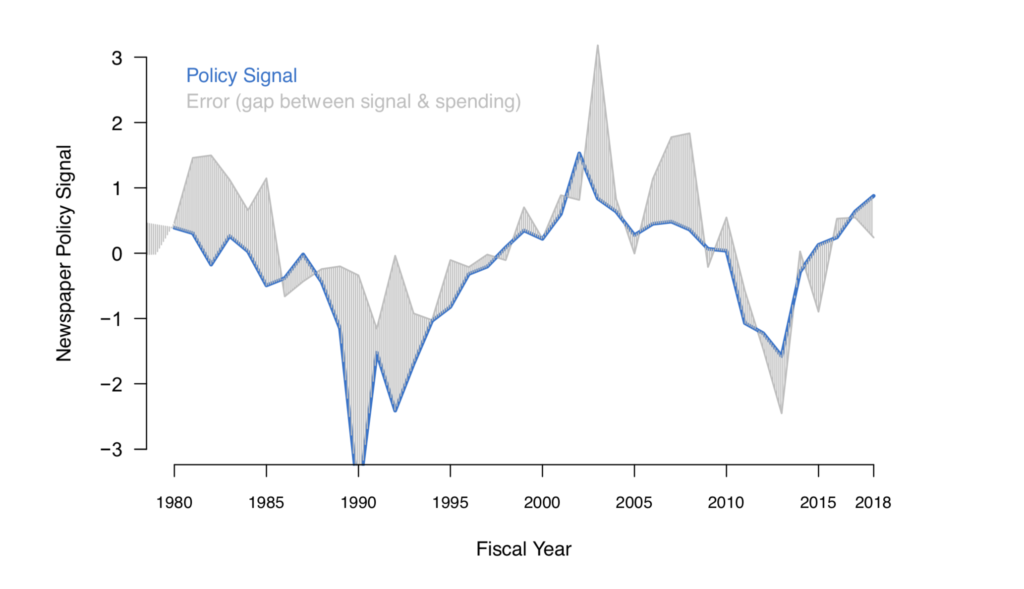

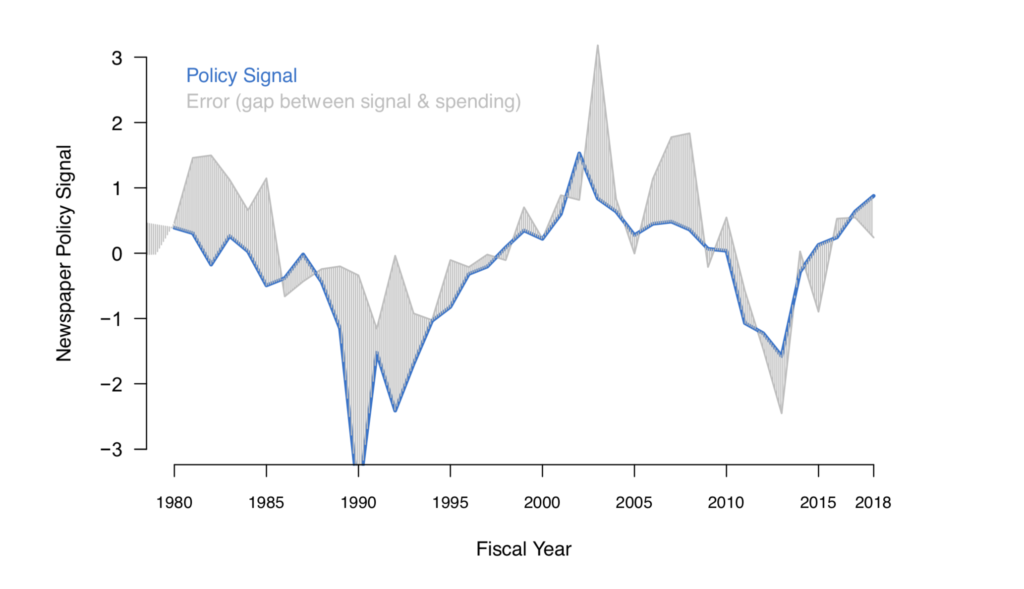

Soroka and Wlezien estimated the policy signal conveyed by the media sources by measuring the extent to which the text suggests that defense spending has increased, decreased, or stayed the same. Comparing this directly to actual defense spending over the same time period reveals the accuracy of year-to-year changes in the media coverage. For example, if media coverage were perfectly accurate, the signal would be exactly the same as actual changes in spending.

As the figure below shows, the signal is not perfect. While there are some years when the media coverage tracks very closely to actual spending, there are other years when there is a large gap between the signal that news reports send and the defense budget. The gap may not entirely represent misinformation, however. In some of these cases, the media may be reporting on anticipated future changes in spending.

For most years, the gap representing misinformation is fairly small. Soroka and Wlezien note that this “serves as a warning against taking too seriously arguments focused entirely on the failure of mass media.” This analysis shows evidence that media coverage can inform citizens about policy change.

The authors conclude that there are both optimistic and pessimistic interpretations of the results of this study. On one hand, for all of the contemporary concerns about fake news, it is still possible to get an accurate sense of changes in defense spending from the media, which is good news for democratic citizenship. However, they observed a wide variation in accuracy among individual news outlets, which is a cause for concern. Since long before the rise of social media, citizens have been at risk of consuming misinformation based on the sources they select.

Sep 1, 2019 | APSA, Current Events, International

Post developed by Pauline Jones, Anil Menon, and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Putin’s Pivot to Populism” was a part of the session “Russia and Populism” on Sunday, September 1, 2019.

The rise in populism around the world has received much attention, but not all populists are the same. In a new paper, Pauline Jones and Anil Menon present an original typology of populists that goes beyond typical left-wing versus right-wing classifications.

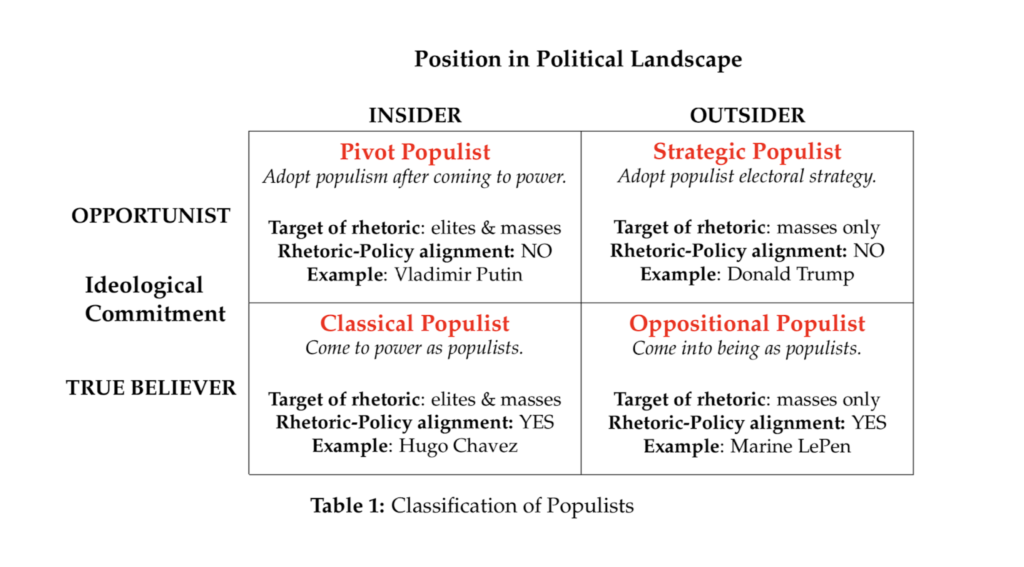

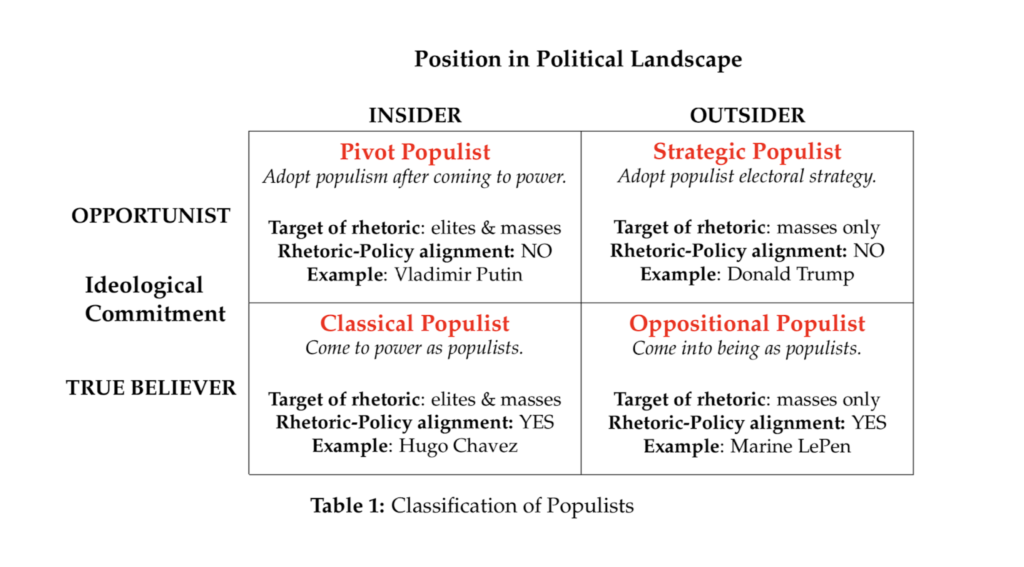

To better understand the different types of populists and how they operate, Jones and Menon examine two key dimensions: position within the political landscape (outsider versus insider), and level of ideological commitment (true believer versus opportunist).

Populists tend to frame their criticism of political elites differently depending on whether they are political outsiders or government insiders. While outsiders are free to criticize those in power broadly, populists who hold political power are more likely to tailor their criticisms to their political opponents. Insiders are also more careful not to attack members of the elite with whom they will need to build political coalitions.

Many populists evoke the past, but outsiders and insiders tend to do so differently. Whereas outsiders focus on the near past as a critique of a corrupt elite, political insiders instead focus on the distant past to evoke better days of shared national values.

Jones and Menon also draw distinctions between true believers in populism and those who embrace populism for purely strategic reasons. True believers will remain strongly committed to enacting their populist agenda once in office; opportunists will use populist rhetoric to gain power, but won’t support their platform strongly if elected.

The intersection of these two dimensions leads to the classification of populists into four types, illustrated in the table below: Oppositional, Classical, Strategic, and Pivot.

The most common variety of populist is the oppositional populist, who are outsiders and true believers. Oppositional populists put their agenda before all else and distance themselves from the mainstream elite.

Classical populists sometimes start out as outsiders who become insiders once they are elected to office. Like oppositional populists, they are strongly committed to enacting their agenda; unlike oppositional populists, classical populists can enact their agenda from a position of power. Because they are insiders, classical populists are more selective about criticizing elites.

Pivot populists are a rare group of political insiders who adopt populist rhetoric with little or no commitment to the populist ideology. Jones and Menon point to Russia’s Vladimir Putin as an example of a pivot populist who has adopted populism to bolster support for his regime while deflecting blame for the country’s problems.

The final category is strategic populists. Like Donald Trump in the United States, strategic populists are outsiders with a weak commitment to the populist agenda. Strategic populists are broadly anti-elite, and also use their rhetoric to create divisions among the people. Once in power, they are unlikely to alienate elites by pursuing populist policy goals.