Feb 20, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, International

Post Developed by Katie Brown and Mark Tessler.

This is the first in a series of posts profiling innovative research projects associated with the Center for Political Studies (CPS) which make their data available at no cost for the public good. Today, we look at the Arab Barometer.

This is the first in a series of posts profiling innovative research projects associated with the Center for Political Studies (CPS) which make their data available at no cost for the public good. Today, we look at the Arab Barometer.

The Arab Barometer is a multi-wave, multi-country political attitude survey. Questions asked concern politics and government, religion and its political role, international affairs, and women’s rights, and status and gender relations.

The first wave of the Barometer surveys, which were carried out in 2006-2007, encompassed Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, the Palestinian Territories, and Yemen. The second wave of surveys, which were conducted in late 2010 and during 2011, included Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen. The surveys in Egypt and Tunisia and most other countries were conducted in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. The third wave of data collection, which will offer even greater contributions, is currently under way and nearing completion. Conducted in transitioning post-Arab Spring societies, the data will gauge attitudes toward elections, government performance, and Islam’s role in government and political affairs.

The Arab Barometer serves both scholars and policy makers. Thanks to the cross-national and longitudinal nature of the data, comparisons can be made across countries and over time. This is especially important given the unfolding of the Arab Spring during the second of three waves of Barometer surveys. A growing number of publications utilize Arab Barometer data. Findings have also been disseminated to policy makers through the Middle East Channel and other outlets and venues.

CPS research professor and University of Michigan professor of political science Mark Tessler and Princeton University associate professor of politics Amaney Jamal are among the co-directors of the Arab Barometer. They and others on the Arab Barometer Steering Committee work with on-the-ground teams in participating Arab countries. Associations with which the Barometer work include the Arab Reform Initiative, an international Arab organization that works for political reform, and the Global Barometer, a world-wide network of regional democracy barometers.

In 2010, the American Political Science Association (APSA) awarded the Arab Barometer the Lijphart, Przeworksi and Verba award for the best publicly available data set in comparative politics.

Feb 18, 2014 | Current Events, Elections, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Kirill Kalinin

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In March of 2012, Vladimir Putin was elected to his third term as President of Russia, after a four year leave serving as Prime Minister. Massive protests and speculation about electoral manipulation and fraud accompanied the election. Yet at the same time, polls ahead of the election predicted a landslide victory by Putin.

Are both the polls and election results incorrect? Could this be explained by social desirability?

Political Science Ph.D. student Kirill Kalinin studies election fraud. Along with Professor of Political Science, Professor of Statistics, and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate Walter Mebane, Kalinin conducted a series of studies that consider the role of social desirability (or the tendency to answer questions not truthfully but in line with public opinion) in the most recent Russian presidential election. This work is possible due to financial assistance from the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, Weiser Center for Emerging Democracies at the University of Michigan, and fruitful cooperation with Henry Hale (George Washington University) and Timothy Colton (Harvard University) within the project of Russian Election Study.

Kalinin focuses on a particular kind of social desirability: preference falsification. Preference falsification pertains to when an individual’s private preferences diverge from public preferences in the context of an election. In the case of Russia 2012, Russian public opinion overwhelmingly supported a strong ruler, i.e., Putin. But did this then push people who would vote against Putin to report to pollsters they planned to vote for him anyhow?

To test this, Kalinin and Mebane conducted a series of list experiments. Run in the month before and after the 2012 election, potential Russian voters were given a list with four statements. Those randomly selected into the sensitive statement condition saw a fifth statement, either about Putin’s electoral support or about voter turnout. Participants indicated how many of the statements they agree with.

Their results overwhelmingly point to preference falsification both ahead and after the election. Specifically, there appears to have been over-reporting both of turnout and electoral support for Putin.

Kalinin concludes that, “In an authoritarian setting like Russia, covering up election fraud is important. This study, however, shows that electoral polling may also be susceptible.” This sets the stage for subsequent election fraud. That is, if Putin is mis-predicted to win, then election fraud can make this win a reality. Poll and election results match but neither is true.

Feb 13, 2014 | Michigan, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Rosemary Sarri.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

400,000 youth are placed out of home in residential treatment institutions in the United States because they were abused or neglected their family. Just 2% of these youth placed out of home in institutions will run away each year, compared to the annual runaway rate of of 6-8% for American youth overall. But the ramifications for the institutionalized runaway youth are grave, including homelessness, poverty, substance abuse, exploitation, and crime.

Center for Political Studies (CPS), School of Social Work, and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri studies the impact of social policy on children. A forthcoming paper with her colleagues Joseph P. Ryan and Elizabeth Stoffregen, who are also of the Institute for Social Research (ISR), considers the serious risks for these youth running away from the child welfare system. The article asks: Does running away from these institutional placements pose an increased risk of future involvement with the juvenile and/or adult justice systems?

Focusing on Wayne County, Michigan, home of the city of Detroit, the study includes 371 children aged twelve or older from the child welfare system that ran away at least once in 2003, matched against similar children in the system that did not run away. The data trace involvement of the youth from the two groups in the justice system over eight years.

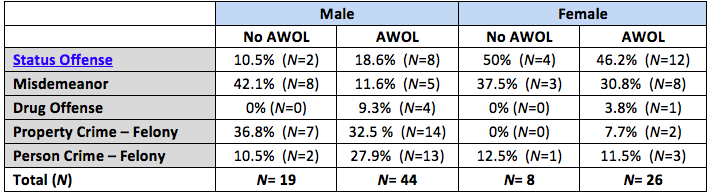

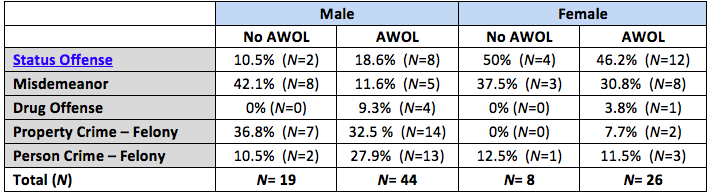

Sarri finds that running away is indeed associated with negative outcomes. Overall, youth who run away from institutional placements have a 40% chance of ending up in the adult justice system. For males, this increases to 71.5%. The table below breaks down the most serious offenses by status and gender for the youth who ran away from institutions. Indeed, youth who run away from institutions commit more serious crimes, especially males.

Most Serious Juvenile Justice Offense by Gender and Runaway Status (the term “AWOL” identifies youth who ran away from institutions)

Given these staggering results, what can be done? Most of the youth are neglected, often with deep issues relating to substance abuse, mental health, homelessness, and crime. As such, Sarri calls for a positive, restorative approach that sets goals and offers resources to help youth achieve them. The Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform have developed an inter-agency collaborative proposal to provide more effective treatment for these “crossover” youth who are at high risk when they drift to the justice system.

Feb 11, 2014 | International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Bill Zimmerman.

On December 16, 2013, Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor Emeritus Bill Zimmerman hosted a very special video conference. Zimmerman and his colleagues from the European University at St. Petersburg celebrated the success of nearly a decade of Carnegie Corporation grants designed to train a new generation of Russian social scientists.

The mission of the project – officially called “Training a New Generation of Russian Social Scientists and Diffusing Social Science Expertise to Russian Regional Universities” – was twofold. First, place young scholars in regional universities in Russia to narrow the social science gap between the capitals (Moscow and St. Petersburg) and the rest of the country. Second, bring aspiring researchers to the University of Michigan to offer further social science training.

After several generous renewals from Carnegie, the program was completed on December 31, 2013, having provided support for 22 emerging scholars. Last month, nearly all participants were able to gather together by video conference to share their experiences. Joining them was Professor Eduard Ponarin, co-investigator of the project and himself a University of Michigan Ph.D. Beginning at 5 p.m. Moscow time (8 a.m. in Michigan), the event lasted approximately two hours. Those in Russia concluded the meeting with dinner.

Speaking a month after the conference celebration, Zimmerman reflected on the event and the program more generally. One unanticipated benefit of the effort was that it resulted in several bright people from regional universities enrolling in the M.A. program of the European University at St. Petersburg. Not surprising was how sharp the Russian scholars were who spent time at the Center for Political Studies. The Russians scholars gained a lot from exposure to what Michigan has to offer, and Michigan was benefited by their presence.

One example of this was contributions by the visiting scholars to the intellectual life of the Center for Political Studies and the University more generally. Three noteworthy examples of successes of the program come to mind. Kirill Kalinin is currently in the last stages of writing his dissertation at Michigan, working primarily with Walter Mebane. Yegor Lazarev, now in the Ph.D. program at Columbia, has a forthcoming paper in the journal World Politics which was originally penned for a seminar taught by Ted Brader. Finally, a paper that was revised by Kirill Zhirkov while he was at Michigan has just appeared in the journal Party Politics. The Center and University are very proud of the Carnegie Scholars and their peers that will undoubtedly be leaders of the next generation of Russian scholars.

Feb 6, 2014 | Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Yuen Yuen Ang.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

What hobbles online activism in autocracies? The intuitive answer: repression. In a recent article titled “Authoritarian Restraints on Online Activism Revisited: Why ‘I-Paid-A-Bribe’ Worked in India but Failed in China” in Comparative Politics, Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate, assistant professor of political science, and Center for Chinese Studies faculty associate Yuen Yuen Ang looks beyond repression — she brings attention to the deeper organizational problems rooted in authoritarian rule.

In 2008, social activists in India created www.ipaidabribe.com (IPAB), a crowd-sourcing website that collects anonymous reports of bribe extraction. By 2014, more than three million users visited India’s IPAB site, with over 20,000 bribe reports filed. Major news outlets covered IPAB. And IPAB soon spread to 17 other countries, including China in 2011.

But, whereas IPAB flourished in India, within two months, all of China’s IPAB sites disappeared. Why?

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Given that China is an authoritarian state, the assumption is that censorship and repression killed the sites. As asserted in the New York Times:

“They [IPAB sites] are threatening enough that when a rash of similar sites popped up in China last summer, the government stamped them out within a couple of weeks.”

Ang’s research, however, finds a more nuanced and complex story. Chinese authorities did not in fact stamp out the sites resolutely, but instead wavered between approval and suppression. More importantly, even before the final shut-down, the IPAB sites had already begun to crack from internal organizational problems. Chinese netizens used the sites to vent, exact personal revenge, and even extract profit and bribes from posting reports.

These problems are rooted in prolonged restrictions that deprive China’s civil society the opportunity to learn the norms of constructive participation and to professionalize. Anonymity on the Internet exacerbates the challenges of self-governance.

Thus, Ang cautions against sanguine views about the revolutionary power of online activism in checking corruption and authoritarian power. The challenge of civic empowerment runs deeper than escaping the shackles of repression. As she concludes,

“Authoritarian rule provides an inhospitable environment for nurturing online citizenship in the full sense of the word, involving not only the exercise of rights and free speech, but also accountability, responsibilities, and trust.”

Commentaries on Ang’s article have appeared on the websites of Personal Democracy Media, ipaidabribe.com, and cnpolitics.org.

This is the first in a series of posts profiling innovative research projects associated with the Center for Political Studies (CPS) which make their data available at no cost for the public good. Today, we look at the Arab Barometer.

This is the first in a series of posts profiling innovative research projects associated with the Center for Political Studies (CPS) which make their data available at no cost for the public good. Today, we look at the Arab Barometer.