Aug 30, 2019 | APSA, National, Policy

Post developed by Brian Weeks and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Can Incidental Exposure to News Close the Political Knowledge Gap?” was a part of the session “News in the Digital Age” on Friday, August 30, 2019.

We’re immersed in a media landscape full of choices. News, information, and entertainment are all at our fingertips. But does this mean that people are better informed about important issues? Is it is possible for people who aren’t interested in seeking out political news to learn about candidates and issues through the information they’re exposed to casually? Brian Weeks, Daniel S. Lane, Lauren B. Potts, and Nojin Kwak conducted two surveys to answer this question.

Motivation and opportunity play a big role in the amount of news we’re exposed to. People who are deeply interested in politics are motivated to seek out information, and as a result, they are better informed about candidates and policies.

The nature of the media environment makes it hard to avoid news and political information; many people consume news without trying. As we have more access to all types of media, we are incidentally exposed to political information. Does increased accidental exposure make up for a lack of motivation to seek out news, or does all of that information rush past us without making us more knowledgeable?

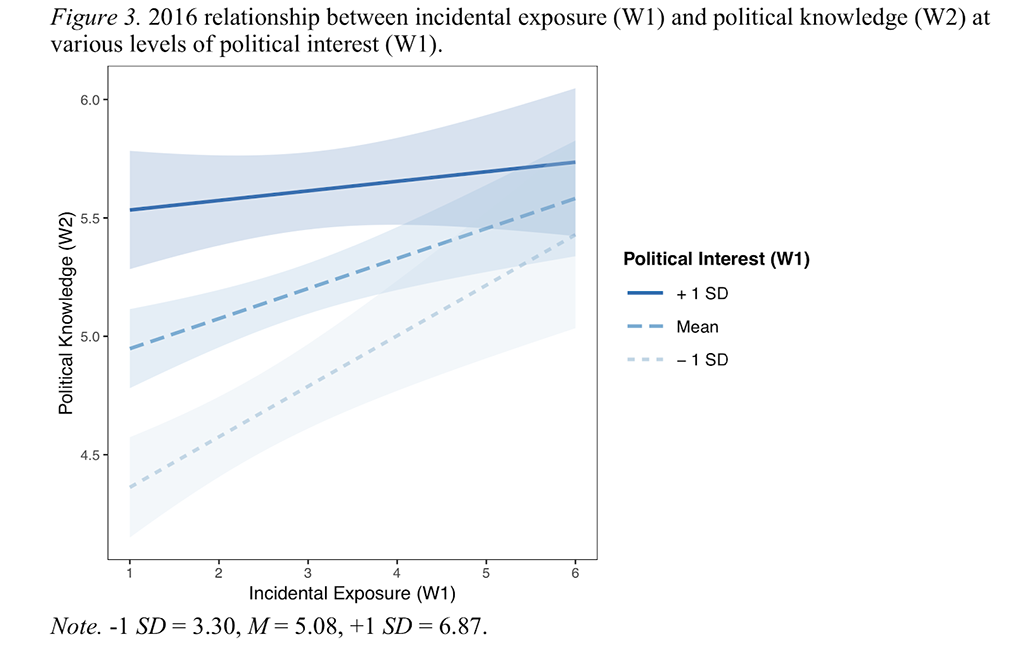

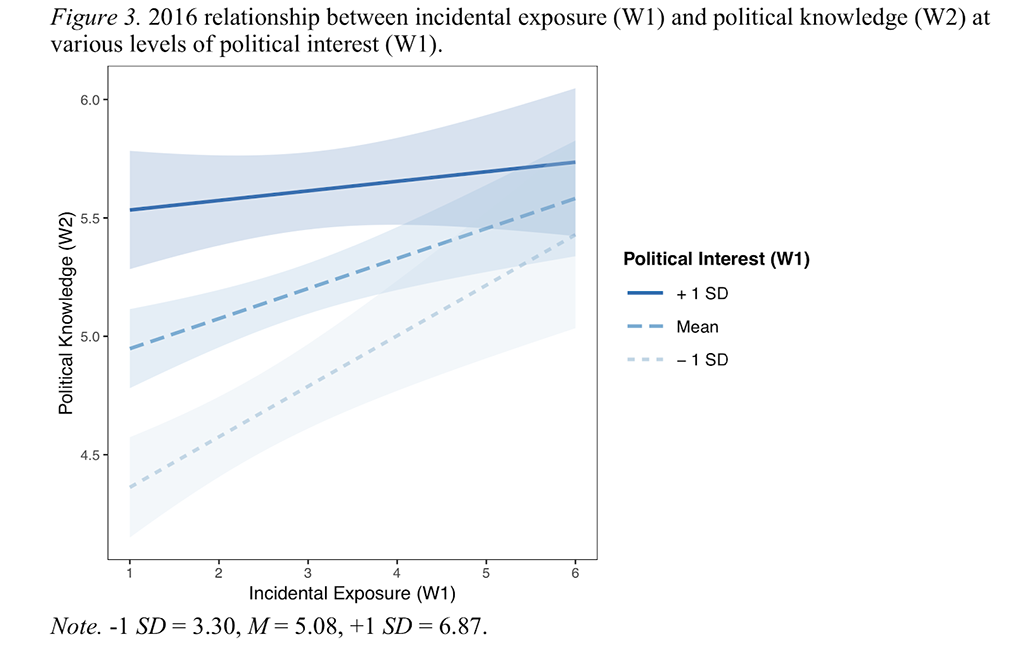

To test whether this incidental exposure to news translates into an increase in political knowledge, Weeks and his co-authors conducted a series of surveys. They collected panel survey data two waves during the 2012 presidential election and conducted another two waves of surveys during the 2016 presidential election. The surveys asked participants about whether they were exposed to political information they didn’t seek out, their level of political interest, and measured their knowledge of candidates’ policy positions.

The surveys showed strong evidence that people who had incidental exposure to news about presidential candidates knew more about the candidates’ policy positions.

The biggest benefit of incidental exposure was seen in the group of people who rated themselves least politically interested, which suggests that greater exposure can make up for a lack of motivation to seek out news.

Knowledge of candidates and their policy positions is still essential for well-informed citizens, and the growth of opportunities to be exposed to news from many sources may reduce gaps in knowledge.

Aug 30, 2019 | APSA, Current Events, Elections, Innovative Methodology

Post developed by Dory Knight-Ingram

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Using Neural Networks to Classify Based on Combined Text and Image Content: An Application to Election Incident Observation” was a part of the session “Deep Learning in Political Science” on Friday, August 30, 2019.

A new election forensics process developed by Walter Mebane and Alejandro Pineda uses machine-learning to examine not just text, but images, too, for Twitter posts that are considered reports of “incidents” from the 2016 US Presidential Election.

Mebane and Pineda show how to combine text and images into a single supervised learner for prediction in US politics using a multi-layer perceptron. The paper notes that in election forensics, polls are useful, but social media data may offer more extensive and granular coverage.

The research team gathered individual observation data from Twitter in the months leading up to the 2016 US Presidential Election. Between Oct. 1-Nov. 8, 2016, the team used Twitter APIs to collect millions of tweets, arriving at more than 315,180 tweets that apparently reported one or more election “incidents” – an individual’s report of their personal experience with some aspect of the election process.

At first, the research team used only text associated with tweets. But the researchers note that sometimes, images in a tweet are informative, while the text is not. It’s possible for the text alone to not make a tweet a report of an election incident, while the image may indeed show an incident.

To solve this problem, the research team implemented some “deep neural network classifier methods that use both text and images associated with tweets. The network is constructed such that its text-focused parts learn from the image inputs, and its image-focused parts learn from the text inputs. Using such a dual-mode classifier ought to improve performance. In principle our architecture should improve performance classifying tweets that do not include images as well as tweets that do,” they wrote.

“Automating analysis for digital content proves difficult because the form of data takes so many different shapes. This paper offers a solution: a method for the automated classification of multi-modal content.” The research team’s model “takes image and text as input and outputs a single classification decision for each tweet – two inputs, one output.”

The paper describes in detail how the research team processed and analyzed tweet-images, which included loading image files in batches, restricting image types to .jpeg or .png., and using small image sizes for better data processing results.

The results were mixed.

The researchers trained two models using a sample of 1,278 tweets. One model combined text and images, the other focused only on text. In the text-only model, accuracy steadily increases until it achieves top accuracy at 99%. “Such high performance is testimony to the power of transfer learning,” the authors wrote.

However, the team was surprised that including the images substantially worsened performance. “Our proof-of-concept combined classifier works. But the model structure and hyperparameter details need to be adjusted to enhance performance. And it’s time to mobilize hardware superior to what we’ve used for this paper. New issues will arise as we do that.”

Aug 30, 2019 | APSA, Current Events, Policy

Post developed by Erin Cikanek, Nicholas Valentino, and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “The Politicization of Policies to Address Climate Change” was a part of the session “The Dynamics of Climate Policy Support in the US” on Friday, August 30, 2019.

Climate change is a truly polarizing issue. Partisans on either side of the issue have such deeply entrenched beliefs that there is little that can change minds. But this wasn’t always the case. For example, in 1988 Democrats and Republicans were in close agreement about the amount of money the government should spend on environmental protection. More recently, partisans have become more polarized in their level of concern about climate change.

How do scientific policy issues become so polarized, and how quickly does this happen? New research by Nicholas Valentino and Erin Cikanek measures public awareness of Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) polices, and explores whether attitudes toward these policies are as politicized as climate change overall.

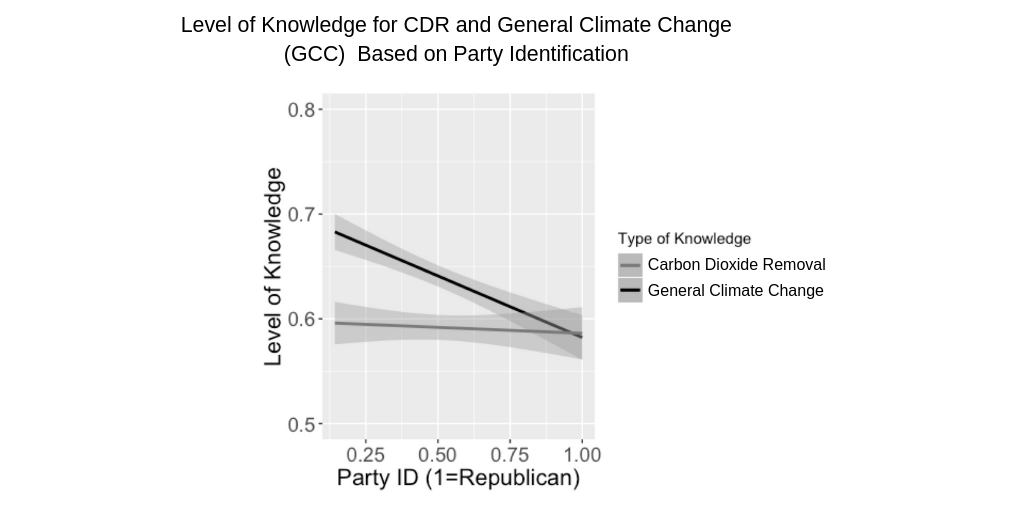

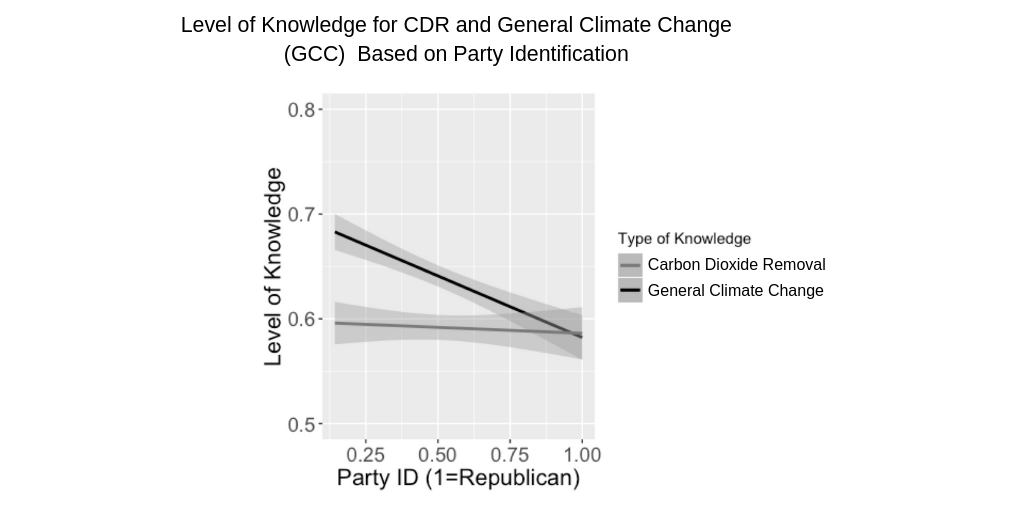

Valentino and Cikanek conducted two studies to examine political polarization of CDR. First, they surveyed a large, nationally representative sample of people to measure how much they knew about climate change. The questions covered a broad set of issues and strategies for dealing with the problem. This survey revealed that the public has a high level of knowledge about climate change.

The study also demonstrates that partisanship is highly predictive of knowledge about climate change. Democrats responded with significantly more accuracy than Republicans did. When respondents were asked specifically about technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, overall knowledge was lower, but Democrats and Republicans answered questions with the same level of accuracy, as shown in the figure below. Valentino and Cikanek note that “this pattern is consistent with the possibility that elite rhetoric has come to suppress accuracy on general climate change knowledge among Republicans, but this has not yet occurred for knowledge in this newer domain (CDR).”

The second study experimentally tested whether CDR policies are sensitive to partisan cues. CDR policies have not been debated as much or as publicly as climate change in general. Are these policies as susceptible to political polarization?

Survey respondents were randomly assigned to one of three groups. A control group was asked about current climate change policies, as well as carbon reduction policies. The first treatment group received information that applied partisan stereotypes to the CDR policies: Republican hesitation about CDR because it might hinder business, and Democratic encouragement to save the environment. The second treatment group received information that ran counter to those stereotypes: Republican support for a pro-business solution to climate change, and Democratic concern that the solution may encourage businesses to pollute.

The partisan cues had very little effect on the response to CDR policies. Interestingly, the counter-intuitive partisan cues backfired: when Republican respondents read the treatment showing Republican support for CDR, they opposed it slightly more. The very weak effect of partisan cues on support for CDR may show that CDR policies may be more resistant to polarization.

The more politicians discuss scientific policy issues, the more polarized the discussion tends to become. However, Valentino and Cikanek see reason to hope that compromises remain possible for issues like carbon removal, which have not yet been subjected to partisan rhetoric.

Aug 30, 2019 | APSA, Current Events, Law, National, Policy, Race, Social Policy

Post developed by Nicole Yadon, Kiela Crabtree, and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Breeding Contempt: Whites’ Reactions to Police Violence against Men & Dogs” was a part of the session “Race and Politics: New Theoretical and Methodical Insights v. Old Paradigms” on Thursday, August 29, 2019.

Of 987 individuals killed by police officers’ use of fatal force in 2018, 209 were black, and, of those, 200 were black men. The targeting and killing of unarmed black men has become a point of interest for news cycles and social movement organizations alike and is indicative of a fraught relationship between communities of color and police. With increasing press coverage over the past decade, academics have also begun to focus on the intertwining relationship between police use of force and race, complementing a long-standing literature which links blacks to perceptions of criminality, violence, and hostility. One area that is not well-developed, however, is how news coverage of police shootings influences attitudes towards police and policies related to policing for white Americans.

Building from research on race, media coverage, and policing, new research by Nicole Yadon and Kiela Crabtree examines reactions to police and policing by white people after they read about a police officer shooting a white man, a black man, or a dog. They find that news reports about police shootings change attitudes about police, but the strength of the reaction varies depending on who the victim is.

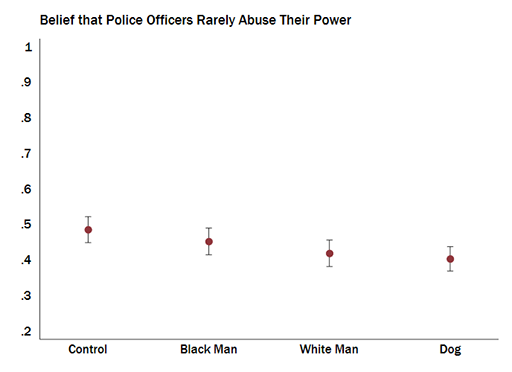

Specifically, Yadon and Crabtree’s study examines white individuals’ feelings towards police following exposure to news of a fatal police shooting. They designed a survey that presents participants with a fictional but realistic news report about a fatal police shooting. In one version the shooting victim is a black man, another reports that the victim is a white man, and in the third version the victim is a dog. Key information about the shooting remains the same across all three versions. A control story, unrelated to race or police shootings, was given to a control group for purposes of comparison with the three treatment groups. This experiment was conducted via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform, with 802 white participants. After reading one of the news reports, participants were asked a series of questions about their perceptions of the events in the article and about their attitudes towards police more broadly.

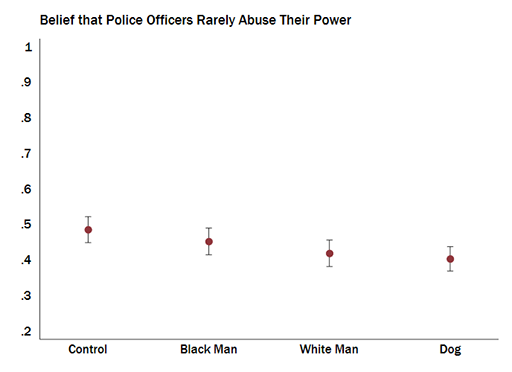

When asked whether they agree or disagree that police officers rarely abuse their power, the control group who had not read about a police shooting had a neutral response — about 0.49 on the 0 to 1 scale. Respondents who read about a white man or a dog being shot by police had a markedly different reaction. Participants who read an article about a white man shot by police had a 7 percentage point decrease in belief that police rarely abuse their power while those who read about a dog shot by a police officer had an 8 percentage point decrease. This is equivalent to survey respondents moving from feeling neutral about whether police abuse their power to a slight disagreement that abuse of power is rare after reading about either a White victim or dog victim.

Importantly, when white survey participants read about a black victim of a police shooting, it did not change their perception of abuse of power by police officers. Put differently, those who read about a black victim held views abuse police abuse of power that were indistinguishable from those who read the control story. The evidence suggests, then, that white respondents react more strongly to a police shooting if the victim is a dog than a black man.

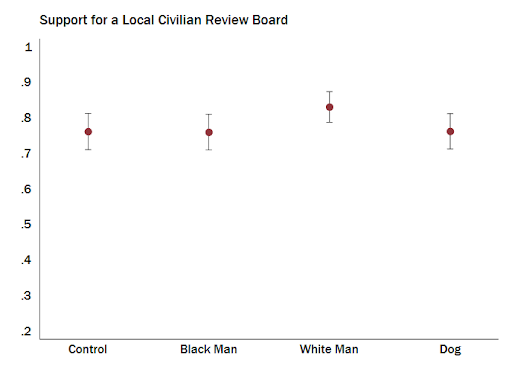

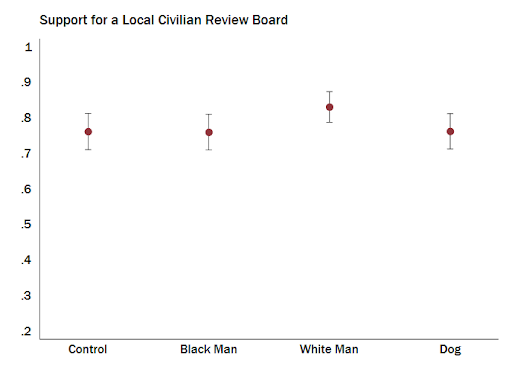

A separate set of questions focused on interest in varying forms of political participation following exposure to the news story. Do white people feel moved toward political participation in response to a story about a police shooting? First, the survey asked whether respondents would support a civilian review board to oversee the police department in their community. Those who read about a police officer shooting a black man or a dog were no more likely to support a civilian review board than the control group. However, those who read about the shooting of a white man were more than 7 percentage points likely to support civilian review in their community.

A second question asked about interest in signing a petition urging Congress to take action towards reducing excessive use of force by police. In contrast to the civilian review board question, levels of support for signing a petition were very low across all groups. In fact, white participants do not appear increasingly motivated to urge Congress to take action against excessive police force regardless of the victim’s identity.

Taken together, Yadon and Crabtree’s results suggest that exposure to a news story about a police shooting draws strong reactions from white people. Of concern, however, is that such reactions are largely limited to viewing either a white man or a dog victim. Indeed, across most of the items which measure attitudes towards police, there are no statistically significant differences when comparing the control condition with the black victim treatment. Such connections are increasingly important to study as cities move toward tightening oversight of police forces and many such initiatives are presented to citizens at the ballot box. Thus, the attitudes citizens hold about police are not only their own. The public’s opinion has potentially lasting effects for the future of policing in local communities.

Aug 29, 2019 | APSA, Elections, International

Post developed by Allen Hicken and Katherine Pearson

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Presidents and/or Prime Ministers: A Historical Dataset” was a part of the session “Legislatures and Leaders: New Perspectives on Political Institutions” on Thursday, August 29, 2019.

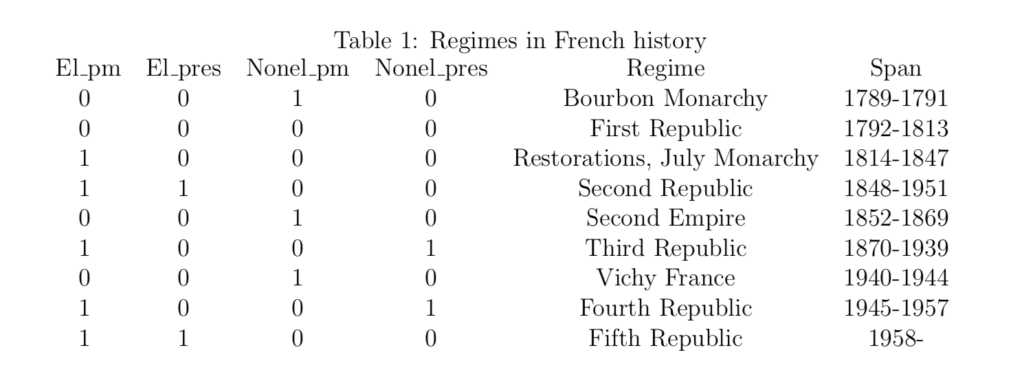

Classifying systems of government is a challenge for political scientists comparing regimes over time and across countries. A new historical dataset developed by Fabricio Vasselai, Samuel Baltz, and Allen Hicken addresses this challenge with a simplified classification scheme that presents data on four broad variables: whether there is an elected prime minister, whether there is an elected president, whether there is a non-elected prime minister, and whether there is a non-elected president. The dataset includes a yearly assessment for almost all sovereign countries since 1789, which amounts to 16,910 country-years.

The simplicity of this classification system allows researchers to examine other characteristics separately, including the level of democracy or the powers of elected leaders. While the majority of country-years fit a neat definition, this dataset allows a clearer analysis of complex cases.

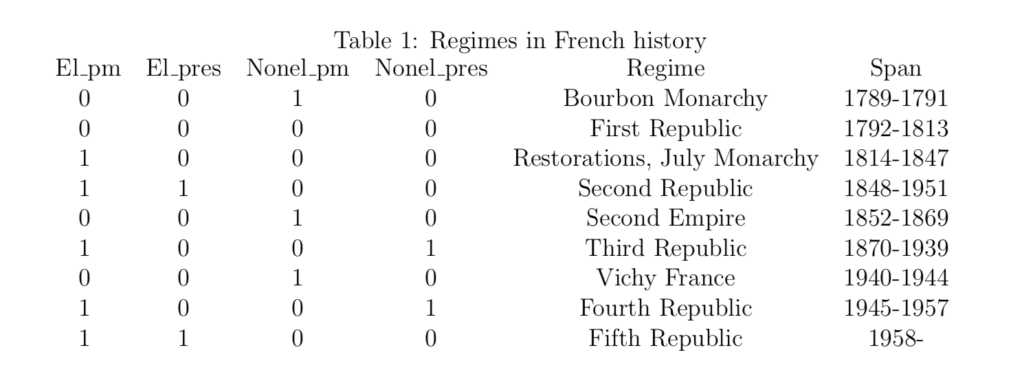

The authors present France as an interesting test case. In the years included in this dataset, France had (1) only an unelected prime minister, (2) no elected or unelected prime minister or president, (3) only an elected prime minister, (4) an elected prime minister and an elected president, or (5) an elected prime minister and unelected president, with several of these states repeating multiple times throughout France’s history. The dataset presents this complicated historical narrative in the simplified manner below.

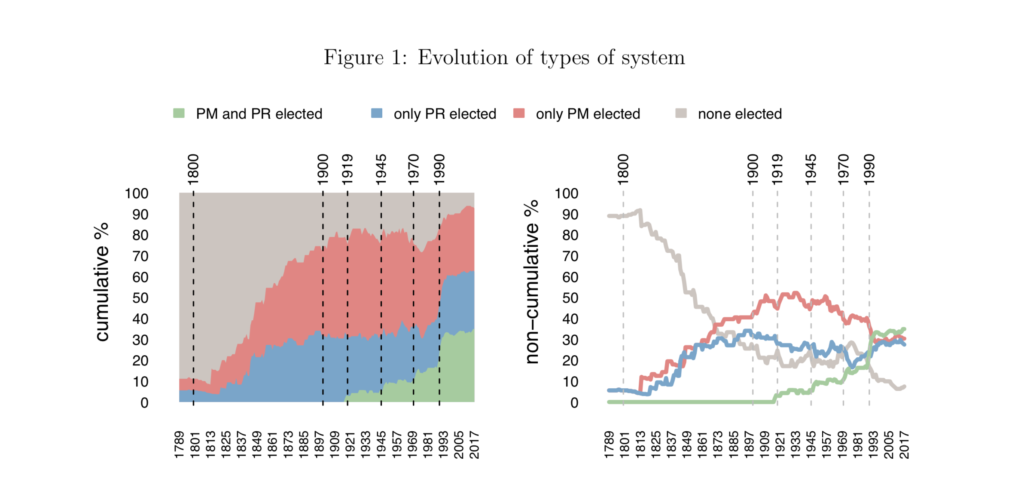

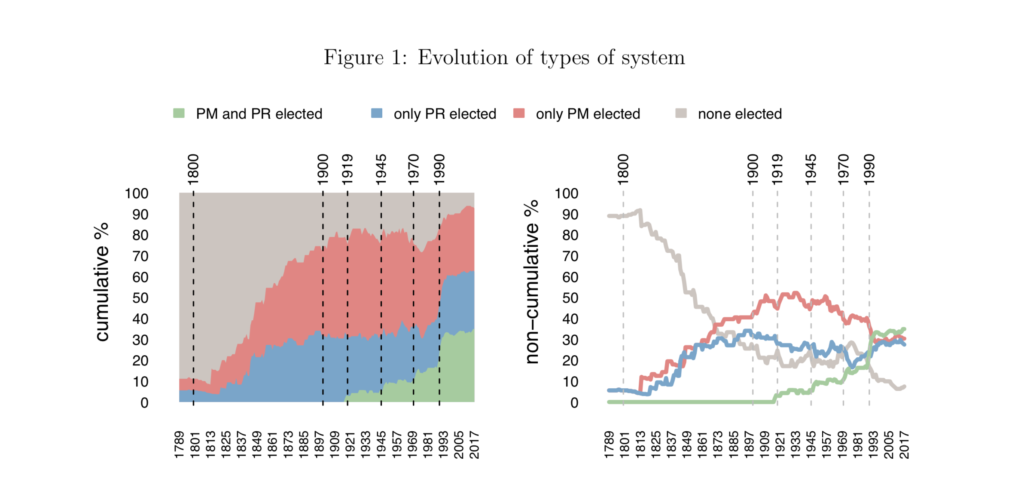

This classification system also allows researchers to explore the evolution of different systems of government over longer periods of time. The authors show that an explosion of elections took place in the 19th century. Beginning in the 20th century, the share of countries electing only a prime minister takes a slight lead; by 1945 almost twice as many countries elected only a prime minister compared to those electing only a president. The share of countries electing either leader climbs through the second half of the 20th century, with only about 10 percent of country-years lacking an elected leader by 2017.

By developing a simple, comprehensive dataset, Vasselai, Baltz, and Hicken have given researchers a resource that allows them to analyze regimes consistently and layer on additional information as needed.