Aug 31, 2014 | Conflict, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Christian Davenport.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “The Domestic and/or International Determinants of State Repression: Examining Spells,” was a part of the Conflict Processes panel “Determinants of State Repression” on Sunday August 31st, 2014.

Since the Holocaust, one of the most important purported tasks of humankind has been to never again let such horrific violations of human rights occur. This mission came with a three-part strategy of preventing, stopping, and prosecuting such violations.

And yet, again and again, grave human rights violations continue to happen: Guatemala, Tibet, Rwanda, and Syria are just a few examples. Christian Davenport, Faculty Associate in the Center for Political Studies (CPS) and Professor of Political Science, along with Benjamin J. Appel of Michigan State University, have examined 220 instances of extreme state repression in recent decades.

The first analysis of its kind and part of a series which will ultimately be published in a book, the 220 examples included in the database occurred between 1976 and 2004. Each scored above a 3 on the Political Terror Scale. Level 3 is characterized by political imprisonment, including executions, no trials, indefinite sentences, and brutality. This escalates to level 4 when civil and political rights violations extend to most of the population and “murders, disappearances, and torture are a common part of life.” The scale maxes out at 5, at which point the entire population is affected by brutality, as the leader will stop at nothing to achieve ideological goals.

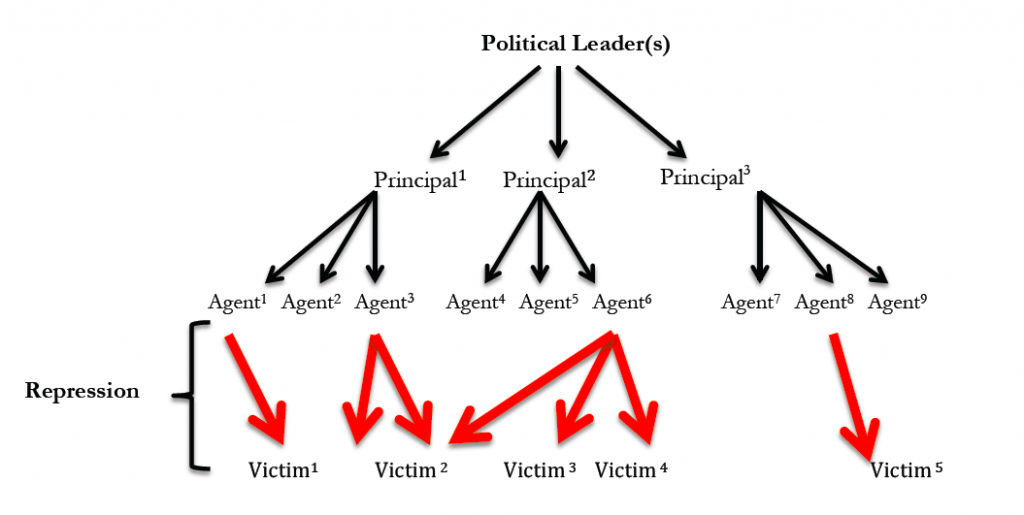

The authors clarify that, while it is the leader’s goals enacted, they do not do their own dirty work. Rather, this role is allocated to principals (e.g., generals), who in turn give the orders and necessary resources to agents (e.g., soldiers and police officers). These agents enact the brutality on victims. The flow chart below delineates this process.

Assigning the Dirty Work of State Repression

The authors’ goal in analyzing the 220 cases of state repression: understand what stops the repression. Davenport and Appel look at both domestic and international factors. International approaches include economic sanctions, military action, public condemnation, and Preferential Trade Agreements designed to make it harder for the repressive government to obtain the means of repression. Increasing democracy within the borders constitutes the domestic answer to repression.

After analyzing the 220 cases, the authors find essentially no support for the international efforts to stop repression, though Preferential Trade Agreements do exhibit an influence. The more powerful and appropriate approach, however, concerns democratization from within. The authors conclude, “If one is trying to stop state repression, then they should consider how best to move the government toward full democracy.” But, the authors caution that they best way to stop state repression is to prevent it in the first place.

Aug 30, 2014 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, Innovative Methodology, International, Law

Post developed by Katie Brown and Muzammil M. Hussain.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Post-Arab Spring Formations of the Internet Freedom Regime,” was a part of the Political Communication panel “From the Middle East to the Million Man March: The Continuing Digital Revolution” on Saturday August 30th, 2014.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

In early 2011 through 2012, unexpected uprisings cascaded throughout the Arab World. News of this Arab Spring swept across the globe, which inspired several other cascades of political change. Communication systems, especially social media networks, offered an immediate and intimate glimpse into these movements, their successes and failures. So how have state powers and political activists responded to the political capacities of this shared and global digital infrastructure?

Communication Studies Assistant Professor and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate Muzammil M. Hussain studies the political economy of Internet freedom activism. In particular, he is interested in the fate of digital infrastructure in “born digital” states, or states which had successful regime changes that were enabled by digital media. The Arab Spring presents a fascinating and recent moment to consider these “born digital” states. Hussain asks what role governments – both the challenged authoritarian states and the emerging democracies – are playing in shaping communication networks. To address this, he focuses on the transnational activities of political activists promoting Internet freedom.

Hussain conducted fieldwork in the Middle East, North Africa, Western Europe, and North America between 2012-2013, after the Arab Spring protests subsided and a new kind of policy activism took root. Through this international network ethnography of policy makers, communications corporations, and political activists involved in the Arab Spring, Hussain collected a massive array of data. The data includes both interviews and participant-observation, with corroborative evidence of 5,000 individuals and their 84,000 social ties, as well as over 2,000 emails generated through their lobbying and activism work.

This meta-database encompasses the three main stakeholders in Internet freedom promotion: state powers, technology providers, and civil society actors. Hussain argues that Western democracies have been important and successful in launching several major initiatives for securing internet freedom and supporting digital activists currently working within repressive political systems. But these efforts to establish an Internet freedom policy regime are currently gridlocked in competing “communities of practice.”

On the one hand, the community of state-based stakeholders have come to narrowly regard digital media as a critical infrastructure, overvalued its significance as an economic interest and undervalued its significance to democratic activists. On the other hand, since the Arab Spring, the community of tech-savvy political activists has moved rapidly into many new communications policy arenas. Finally, revelations of warrantless surveillance by several advanced democracies have also threatened the viability of this Internet freedom regime. So what are democratic activists and Internet freedom promoters left to do? Stay tuned for Hussain’s next book project: Securing Technologies of Freedom: Internet Freedom Promotion after the Arab Spring.

Aug 29, 2014 | Current Events, Innovative Methodology, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Yuri Zhukov.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Measuring Rape Culture,” was a part of the Political Methodology theme panel “Big Data and the Analysis of Political Text” on Friday August 29th, 2014.

In August of 2012, two high school football players raped a young woman in Steubenville, Ohio. Instead of intervening, witnesses recorded the incident, posting photos and videos to social media sites. The social media trail eventually led to a widely publicized indictment and trial. Yet while the two teenagers were convicted of rape, coverage of the case nonetheless came under fire for perpetuating rape culture. News outlets displayed empathy for the rapists while blaming the victim.

When the media cover sexual assault and rape, empathizing with the accused and/or blaming the victim may send the message that rape is acceptable. This acceptance in turn could lead to an increase in sexual violence, with perpetrators operating with a perceived sense of impunity and victims remaining silent. Yet there exists no systematic study of the prevalence or effects of the media and rape culture.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate and Assistant Professor of Political Science Yuri Zhukov, along with Matthew A. Baum and Dara Kay Cohen of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, are filling this gap with a systematic investigation of rape culture reporting in the news media through an analysis of 310,938 newspaper articles published between 2000 and 2014.

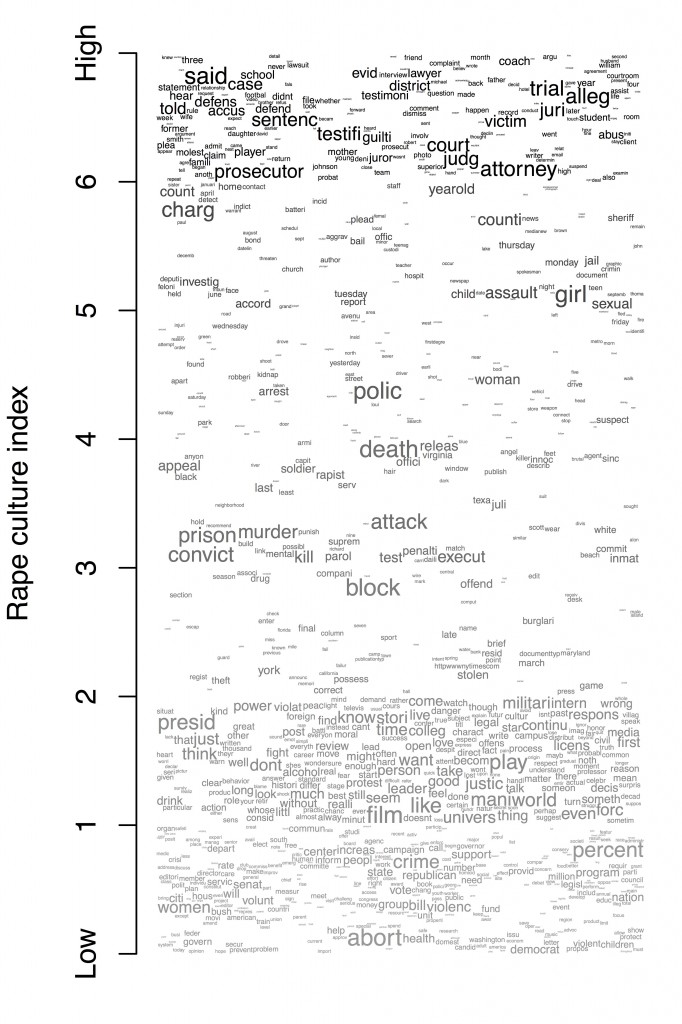

The authors first had to operationalize the concept of rape culture, to date a diffuse term. In addition to perpetrator empathy and victim blaming, the authors added implications of victim consent and questioning victim credibility as fundamental dimensions of the concept. The authors then broke down each of these four categories into more detailed content, resulting in 76 descriptors of rape culture. Trained coders analyzed a random subset of some 13,000 newspaper articles. Zhukov and his colleagues then used these manually coded articles to “train” a computer algorithm to detect rape culture in a previously unseen body of text. The algorithm then assigned each of 310,938 articles an overall score on a 6-point Rape Culture index, with higher scores corresponding to articles with more rape culture language.

While the study offers many provocative and important findings, we will focus on an innovative and startling result. The authors created a word cloud mapped onto the rape culture index.

Articles with scores on the lower end of the index tended to discuss rape in the context of crime in general or domestic politics. Articles in the mid-range tended to discuss it in the context of that particular crime, the fate of the accused, and the response of law enforcement. Articles high on the index tended to be about court proceedings (and refer to the victim as “girl,” especially “young girl”) or to athletic institutions. Based on the word cloud graph, the authors conclude that: “Rape culture is less apparent in the initial stages of a case, when news stories are more focused on covering the facts of crimes,” and “Rape culture is strongest when individual cases reach the justice system.”

The authors find that rape culture is quite common in American print media: over half of all newspaper articles about rape revealed information that might compromise a victim’s privacy, and over a third contained language recognized by the algorithm as victim-blaming, empathetic toward the perpetrator, or both. Contrary to popular belief, preliminary findings suggest that rape culture does not depend on the strength of local religious beliefs, or local crime trends. However, the authors find a strong correlation with local politics and demographics: the higher the female share of the population where an article is published, the less likely that article is to contain rape culture language.

Aug 28, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Nicholas Valentino.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “The Attitudinal Structure and Political Consequences of Group Empathy,” was a part of panel “32-8. Race and Political Psychology” on Thursday August 28th, 2014.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

Group empathy is the ability to see through the eyes of another, to take their perspective and experience their emotions. The ability to experience empathy is adaptive in families and friendships. But how can we best measure empathy? And how do life experiences condition one’s ability to feel empathy?

Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor and Professor of Political Science Nicholas Valentino, along with Cigdem Sirin-Villalobos and Jose Villalobos, both of the University of Texas, El Paso, seek to answer these questions. To do so, they conducted a survey with Knowledge Networks. The survey included 1,799 participants, of which 633 were White, 614 Black, and 552 Latino/a.

The authors contend that empathy is not just the ability to take another’s perspective, but the motivation to do so. To this end, they asked 14 questions to create a “Group Empathy Index” (GEI). Examples of the items included statements such as “The misfortunes of other racial or ethnic groups do not usually disturb me a great deal” and “I am often quite touched by things that I see happen to people due to their race or ethnicity.” They also asked about empathy toward specific groups. Analysis showed the new scale to be both reliable and valid.

In addition to better measuring empathy, the authors wanted to understand the role of related personal traits. They found that race, gender, and education condition empathy. In particular, being a minority or a woman, and having more education, are related to higher empathy. Further, personally experiencing unfair treatment by law enforcement also related to higher empathy. Minorities reported more unjust treatment by law enforcement, which might underlie the different levels of empathy by race.

The survey also included questions to gauge political implications of empathy. The study found that those who display higher empathy showed greater support for immigration, valued civil liberties more than societal security, and were more likely to volunteer and attend rallies. The authors concluded that, “Such variations in empathy felt toward social groups other than one’s own may thus have powerful political consequences.”

Aug 19, 2014 | International, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Arun Agrawal.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate and Professor in the School of Natural Resources and the Environment (SNRE) Arun Agrawal studies environmental policy.

Professor Agrawal and the International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) program he coordinates just received a grant of 1.9 million pounds (about $3.2 million) over four years from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID).

Agrawal’s proposed research seeks to improve measurement of the outcomes of forest investments. Forest investments try to minimize the negative impacts of forest-related changes: by influencing land use, agriculture, institutions, migration, and commodity production. Substantial forest investments have occurred in the past few years, driven in part by concerns about climate change and the role of land changes in contributing to global emissions. Assessing the impacts of these programs, therefore, and improving their effectiveness is urgent. As Agrawal explains, “there is a lack of rigorous and generalizable empirical analyses of the effectiveness of past forest investments. Existing knowledge is often anecdotal, based on non-systematically selected indicators, usually supported only by information from a small number of unrepresentative cases, and through studies without rigorous counterfactual analysis.”

With this grant, Agrawal and his collaborators will methodically study the impact of forest investments with empirical data and quantitative analysis. In particular, Agrawal will seek answers to three key questions:

- What is the impact of specific types of forest interventions across different policy and governance contexts?

- Where and under what conditions do forest interventions deliver positive impacts?

- Which forest interventions have resulted in more positive impacts and why?

The research will focus on Brazil, Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, and Nepal, using these countries to generate rigorous, valid, reliable, and generalizable findings.