Jul 29, 2013 | Current Events, National

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Michael Traugott and Ashley Jardina.

On February 26, 2012, George Zimmerman fatally shot unarmed African American teenager Trayvon Martin in a Florida gated community. Several weeks later, amid media hysteria and public outcry, Zimmerman was arrested and charged with second degree murder.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

On July 13, 2013, a jury of six women found Zimmerman not guilty of murder or manslaughter.

Polls after the verdict show that while blacks generally disagree with the verdict, whites tend to support the ruling. A few days after the verdict, President Obama gave a twenty minute press conference. In his address, he said that, “Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago.”

Obama’s comments also speak to suspicion he has faced as a black male in the United States. Has race figured into evaluations of Obama? In particular, how does race figure into beliefs that Obama was not born in the United States, a.k.a., the Birther movement?

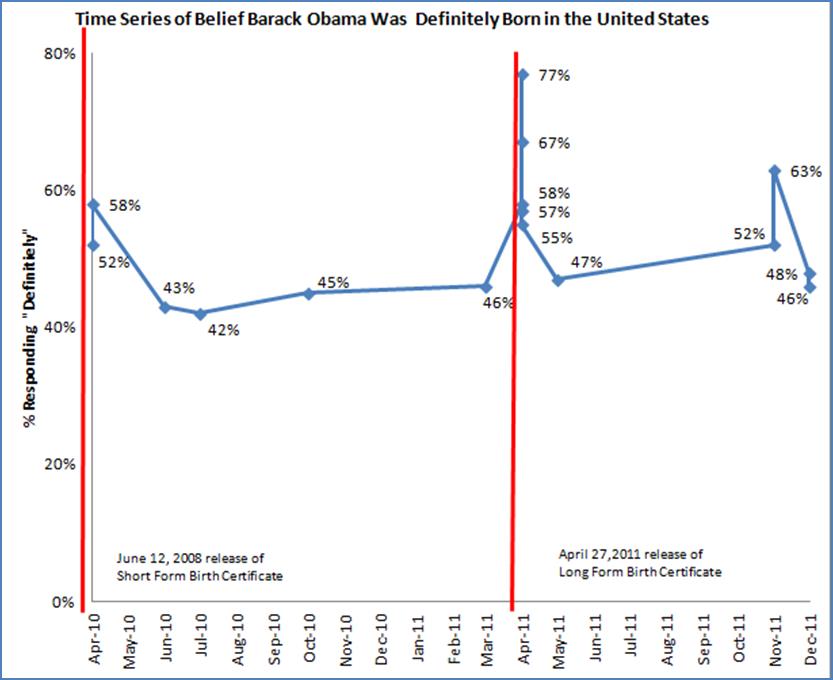

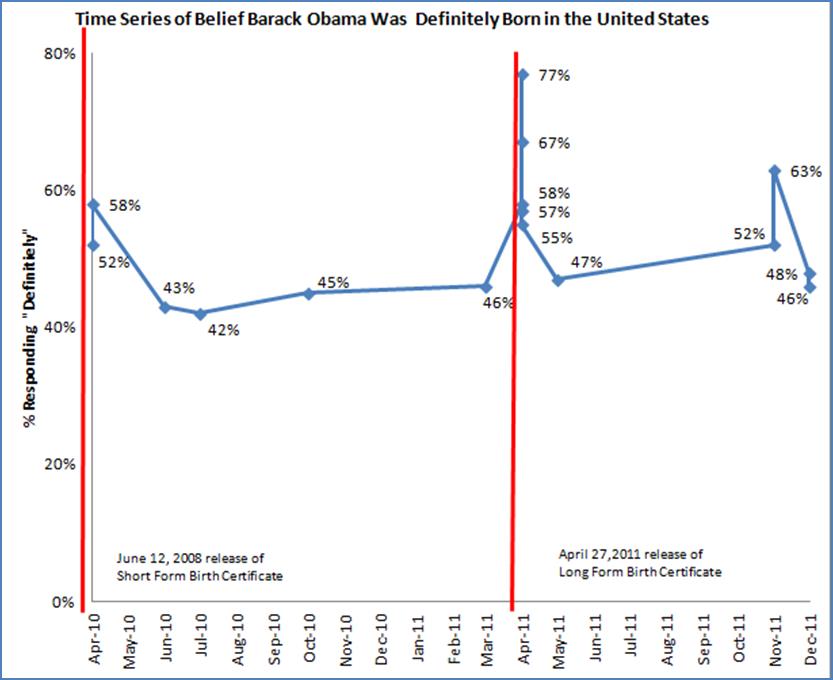

Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher and Professor of Communication Mike Traugott, along with Political Science graduate student Ashley Jardina, conducted a study on Birtherism and its antecedents. Since Obama’s first White House campaign, speculation about his citizenship and origin has made headlines. Belief to the contrary has decreased only slightly, even though Obama’s birth certificate has been released twice: the short form in 2008 and the long form in 2011. The figure below presents the results of 17 different surveys to show this trend over time.

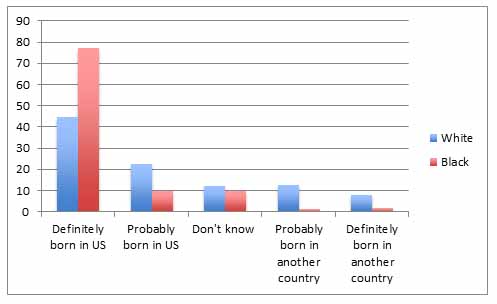

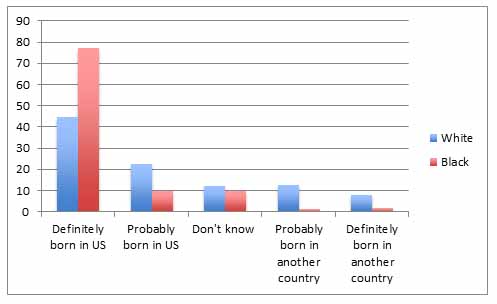

Traugott and Jardina administered a web survey with a stratified sample to include 300 white, black, and Latino Americans. The survey asked, “Was Barack Obama definitely born in the United States, probably born in the United States, probably born in another country, or definitely born in another country?” Comparing the results between white and black shows that whites are more likely than blacks to doubt Obama’s American origins. The graph below displays the answers by participant race.

Was Barack Obama definitely born in the United States, probably born in the United States, probably born in another country, or definitely born in another country?

The survey also suggests that a belief Obama was born outside the United States is also related to lower levels of political knowledge and education, and higher frequencies of forwarding political emails.

In his statements after the Zimmerman verdict, Obama called on the nation to do some soul searching on race. His statement that “Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago” reverberates to today, when belief that he is American remains in question to some, more so among whites than blacks.

Jul 8, 2013 | Innovative Methodology, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Nicholas Valentino.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Two weeks ago, the Gang of Eight immigration bill passed in the Senate. The bill overhauls immigration policy, from border security to legalizing undocumented citizens. The bill passed 82-15. While the Senate support was a large majority over the 60 needed, the 15 votes against came from Republicans.

Prior to that, House Speaker John Boehner (R) highlighted the party lines of such overhaul, saying, “I don’t see any way of bringing an immigration bill to the floor that doesn’t have majority support of Republicans.” He vowed not to bring the bill to a vote in the House without majority Republican support upfront.

Support for immigration varies powerfully along party lines, but the explanation for this difference does not appear to be a simple matter of economic interest.

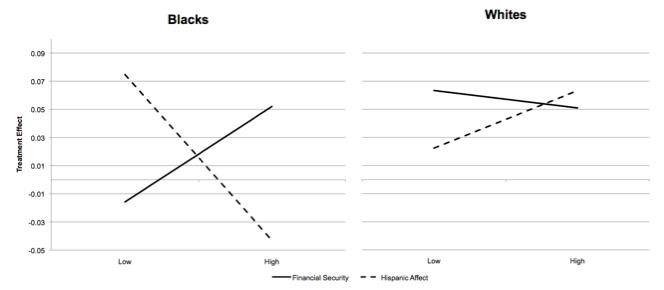

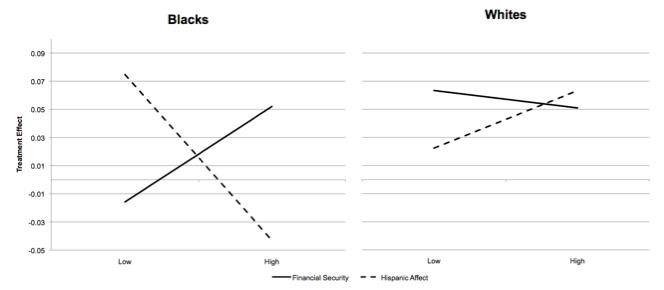

Forthcoming research by Center for Political Studies Researcher Nicholas Valentino, along with Ted Brader and their students Ashley Jardina and Timothy Ryan, shows that despite higher levels of competition for jobs and wages, blacks are less hostile to immigration than whites. The researchers suggest that this gap in support is explained best by differences in empathy for the dominant immigrant group in the U.S., Latinos.

Survey research from the Globalization Threat Study show that blacks are more supportive of immigration than whites. American National Election Studies data also support these results. A powerful explanation for the gap appears to be differential feelings toward Latinos: Blacks feel much more warmly toward this group than whites, and these differences account for different policy preferences on immigration. Using an experiment, the researchers also gauged the malleability of these attitudes. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three news conditions: a positive story about immigration, a negative story about immigration, or an unrelated story. Results suggest that blacks are more resistant to negative news stories about immigration than whites.

This research counters past works that suggests that minorities may be less supportive of other minorities, as these groups tend to have to compete for a smaller slice of the pie. In fact, the researchers distinguished between financially secure and insecure blacks and found the least secure blacks in their study were most likely to reject news accounts that blamed immigrants for social problems.

As Valentino concludes, “Symbolic attitudes are powerful and expansive, crossing ethnic lines to bind groups with competing interests.”

Jul 2, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Christian Davenport (@engagedscholar).

On June 13, 2013, news of the political terror in Syria reached a breaking point. Under President Bashar al-Assad, 92,000 Syrians have been killed. Recent evidence suggests the use of chemical warfare, including sarin gas. Though the civil war has festered for years now, the global community is only beginning to respond. In the wake of this new information, the White House ordered aid to select rebels. On June 18, 2013, the G8 summit supported urgent peace talks in Geneva with Syria. Regardless of how the world’s super powers intervene, the violence is staggering. How can we understand such repressive strategies?

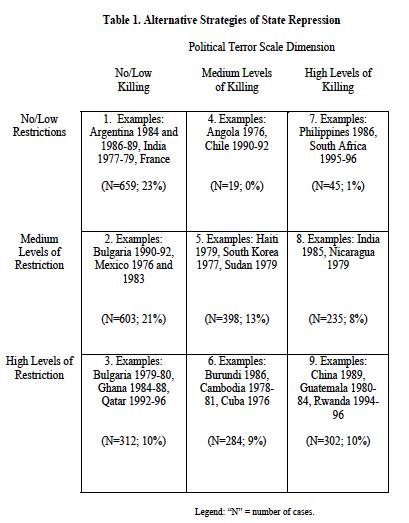

Center for Political Studies researcher Christian Davenport’s work on violent dissent offers insight into Syria’s present state. Davenport’s research uses the Political Terror Scale to operationalize physical torture and elimination of citizens. Both Amnesty International and the U.S. State Department rate Syria at the highest end of this scale, with a 5, defined as: “terror has expanded to the whole population. The leaders of these societies place no limits on the means or thoroughness with which they pursue personal or ideological goals.”

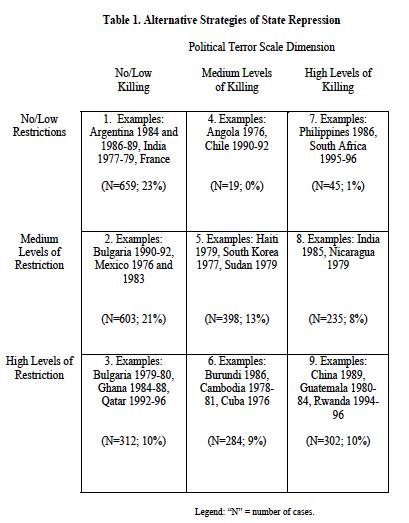

Davenport creates a conceptualization that goes one step further. The resulting grid plots level of restriction against level of killing. Syria rates high on both accounts, making the current situation comparable to other notorious times and places: China in 1989, Guatemala in 1980, and Rwanda from 1994-1996.

Davenport creates a conceptualization that goes one step further. The resulting grid plots level of restriction against level of killing. Syria rates high on both accounts, making the current situation comparable to other notorious times and places: China in 1989, Guatemala in 1980, and Rwanda from 1994-1996.

Davenport’s research emphasizes the dire nature of the situation in Syria. We have little insight into how such activities are ended (something that is sorely needed), but one thing that we do know is that within such situations political leaders are not as sensitive to external policies that under normal circumstances would seem quite costly.