May 29, 2014 | ANES, Current Events, Innovative Methodology, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Spencer Piston.

The gap between the rich and poor in the United States is growing. Occupy Wall Street, fast food worker strikes, and other manifestations of this gap make headlines often. And just a few weeks ago, President Obama visited the University of Michigan to champion raising the minimum wage.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Despite these movements, previous academic work suggests Americans look down on the poor. The news media perpetuate this message. The Economist claims, “Americans want to join the rich, not soak them,” while The New York Times published an article with the headline, “New Resentment of the Poor.”

But what if previous research and the mainstream media are wrong? What if anti-rich movements better capture the American ethos? Center for Political Studies (CPS) affiliate and Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan Spencer Piston investigated this issue.

Piston addresses this question with an innovative approach. Previous scholarship measures attitudes with questions about “economic inequality” and “government-led redistribution.” But these are terms that survey respondents rarely use without prompting, and Piston finds reason to believe that many Americans don’t understand what these terms mean.

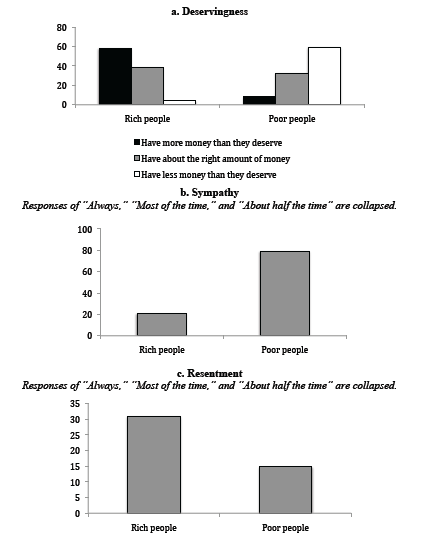

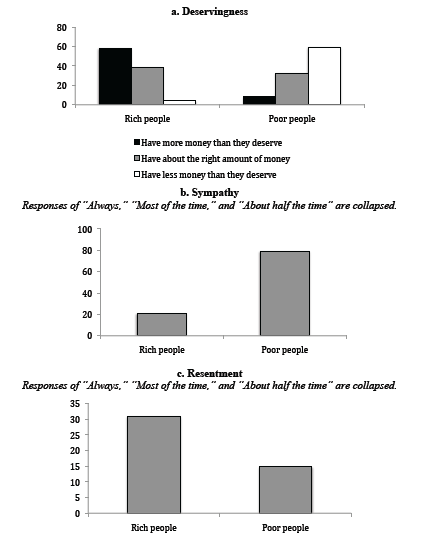

Piston therefore begins with a straightforward but rarely-used survey technique: he asks people how they feel about the poor and the rich. Piston examines answers to these questions using an original survey, and supplemented with American National Election Studies (ANES) data. The graphs below depict feelings of (a) deservingness, (b) sympathy, and (c) resentment toward and the rich and the poor. As we can see, people tend to see the rich as deserving less and the poor deserving more. They also see the poor as more sympathetic than the rich, and the rich as objects of more resentment than the poor.

Feelings toward the Rich and Poor

a. Do the (rich, poor) have more or less money than they deserve?

b. How often have you felt sympathy for (rich, poor) people?

c. How often have you felt resentment toward (rich, poor) people?

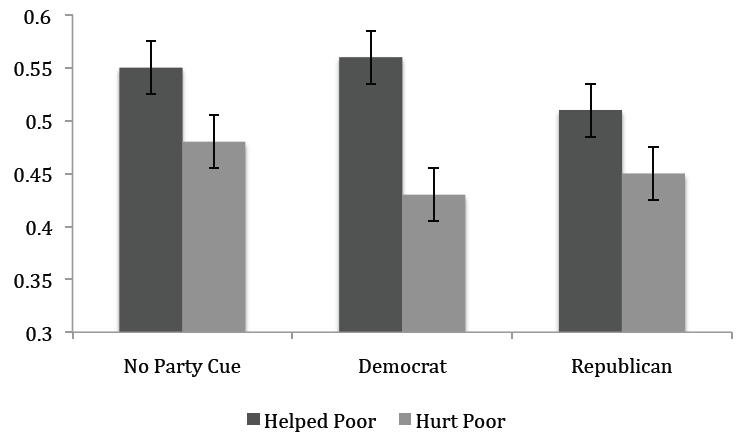

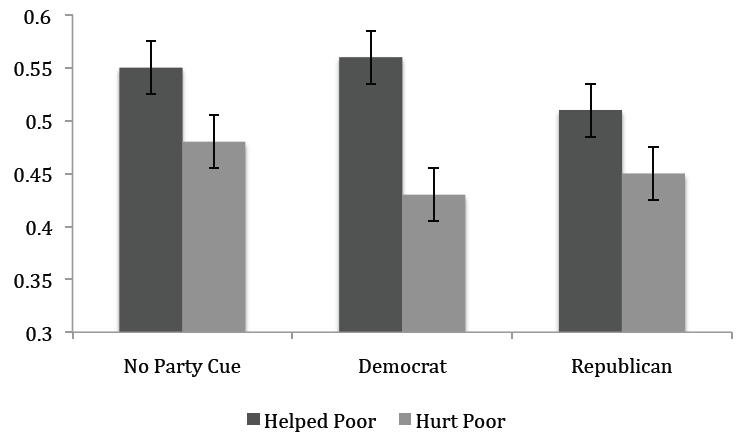

What effect might these Robin Hood attitudes have on elections? Piston tested this with several survey experiments. He finds that that a candidate who supports the poor garners more support among voters than an otherwise identical candidate who hurts the poor, regardless of the candidate’s party.

Effects of Candidate’s Record on Mean Support for the Candidate

Taken together, these results suggest that previous research has overestimated public support for economic inequality and public opposition to downward redistribution. When survey questions are worded using terms that survey respondents more commonly use, it appears that many Americans want government to give more to the poor – and to take from the rich.

Spencer Piston will join Syracuse University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Political Science.

May 22, 2014 | ANES, Elections, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ioannis Andreadis.

Voting Advice Applications (VAAs) are web platforms that help voters determine the candidate or the political party that best matches their own political ideology. Visitors answer a series of questions to gauge their political positions. The VAA platform then estimates the similarity or dissimilarity of these positions to those of candidates or parties.

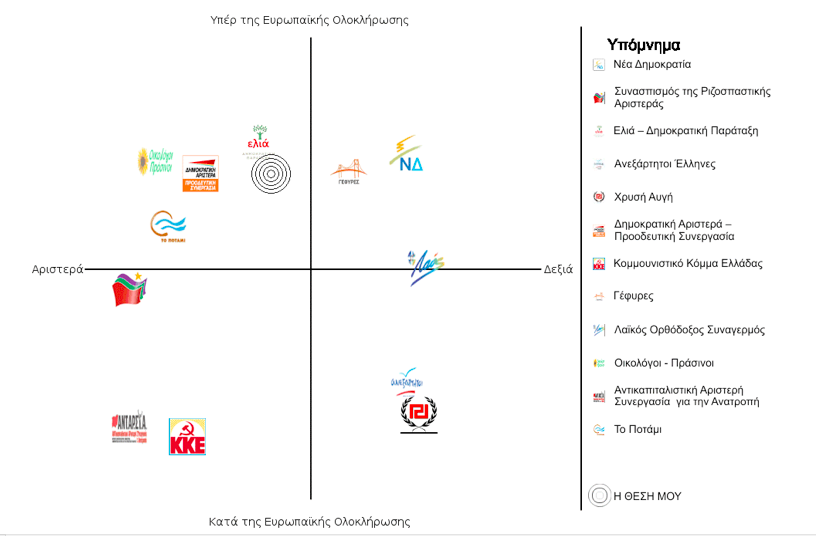

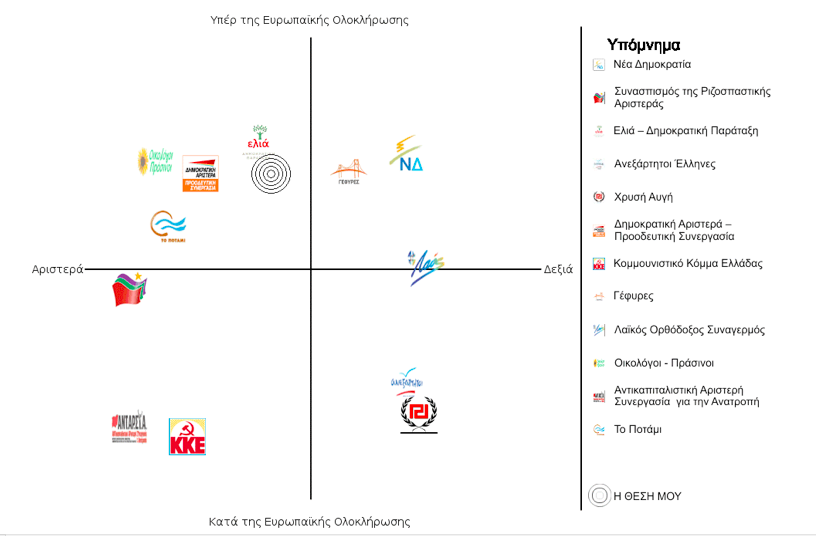

There are various ways to present these estimates. One option is to display a list of the candidates or parties along with a number indicating the similarity or dissimilarity of each. Another option is a graph like the one below from Greece, where issues from the election are represented on each axis, and users can visualize their ideological position relative to that of the parties.

-

Example of diagram from the Greek VAA www.votematch.gr from the elections for the European Parliament. Left/Right is represented by the horizontal axis and Pro-Europeanism/Euroscepticism is represented by the vertical axis. The political party logos indicate their ideological position and the center of the concentric circles indicates the position of the user.

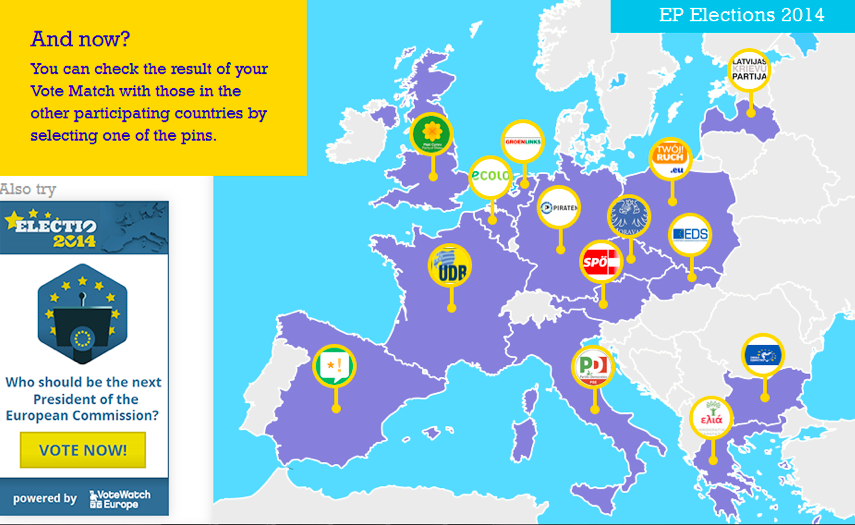

Another example of VAAs in action is Vote Match Europe, an international network of VAAs for the 2014 European Parliament elections across fourteen EU countries. The Vote Match Europe website allows users to see the parties closest to them across all of the countries in the network, and to learn more about the parties and their policies. A goal of the Vote Match Europe website is to promote European citizenship and better inform citizens about the elections for the European Parliament at large.

Ioannis Andreadis is Assistant Professor of Quantitative Methods in the Department of Political Sciences at Aristotle University Thessaloniki. This semester, he is a scholar in residence at the Center for Political Studies (CPS), seeking to learn more about the American National Elections Studies (ANES) and the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) under a grant from the Fulbright Program.

In his capacity as a researcher, Andreadis has studied and written about VAAs, and he also both designs and studies VAAs. In particular, he created and oversees the Voting Advice Application HelpMeVote. HelpMeVote was used by more than 480,000 voters during the May 2012 Greek Parliamentary Elections. The application was also used in Iceland and Albania, and is currently being used for the 2014 European Parliament election.

In a recent paper, Andreadis tackles the question of utility of VAAs. He suggest that VAAs must be built to high academic standards, and realize the following benefits:

- VAAs help voters should become more knowledgeable about party positions, allowing the voters to make better choices.

- VAAs help political parties not covered in traditional media to connect with voters who agree with their values.

- VAAs generate data that researchers can use to better understand voting behavior.

VAAs are growing in popularity in places with multi-party systems and high Internet availability – for example, in Western Europe.

In electoral systems with only two parties, VAAs may be less useful given the limited choice set. If a VAA had been used for the 2009 Greek elections or earlier – when two major Greek political parties dominated national politics – it probably would not have been as popularly used. But in the 2012 elections, the Greek parliament featured seven parties, making way for a new VAA market.

With this in mind, adaptation to America’s two party system poses challenges. VAAs could be used in American primaries, where many candidates from the same party compete against each other, but only if candidates running in the same primary have very different positions on enough issues.

May 15, 2014 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and William Zimmerman.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Russian President Vladimir Putin often makes headlines. This week, U.S. sanctions against Putin in the wake of the Ukraine crisis dominated the news, while Putin’s rewrite of recent music history appeared in popular culture news. Why is Putin such an interesting figure in America? Is it because he challenges our notions of “normal”?

On April 27, Princeton University Press released Ruling Russia: Authoritarianism from the revolution to Putin, the latest book by Center for Political Studies (CPS) Professor Emeritus William Zimmerman. Ruling Russia traces Russia’s history over the last century. The definition of normalcy varied with Russia’s leaders. Gorbachev and Yeltsin for all their differences conceived normalcy to correspond with Western political systems while the leaders of the failed coup against Gorbachev in 1991 and Putin more recently have defined normal to equate with stability, security, and absence of change.

Zimmerman argues that there have been plural Soviet systems and plural Russian political systems and provides a typology to encompass the government types across the century from the revolution to today which distinguishes among democratic, competitive authoritarian, full authoritarian, and totalitarian regimes.

With that as background we can consider the last two decades to better understand current politics in Russia. From 1996 to 2008, after a brief move toward democracy, Russian elections became less open, less competitive, and more meaningless. This time period witnessed Putin’s first (2000) and second (2004) election to President. With Putin unable to run for a third consecutive term in 2008, Dmitry Medvedev ran for President and Putin became Prime Minister.

Then, Medvedev and Putin “castled” in 2012, with Putin running again for President and Medvedev being named Premier. While some believe this move was agreed upon between Putin and Medvedev back in 2008, there is no evidence of this. Zimmerman believes Putin put forth the idea in 2011. Regardless, and interestingly, the 2011-2012 election cycle was more competitive and less predictable than its predecessors. Putin ran a campaign supporting the status quo, stability, and nationalism – a return to normalcy.

The book’s historical analysis ends in 2013. Zimmerman sees full authoritarianism as the most likely near term evolution. This would map onto recent events, including the crackdown on homosexuality during the Sochi-hosted Olympics and military aggression in Ukraine.

From an American vantage point, each move away from democracy was a move away from normal. But for Russia, the idea of “normal” moved toward authoritarianism.

Zimmerman dedicates the book to his students, stating that insights from their dissertations inspired multiple parts of the book.

May 13, 2014 | Elections, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Brian Min.

With six weeks of phased voting, 80% of potential voters are expected to cast ballots in India, making it the world’s largest election. Already marked by political posturing and violence, the elections also include the politics of light.

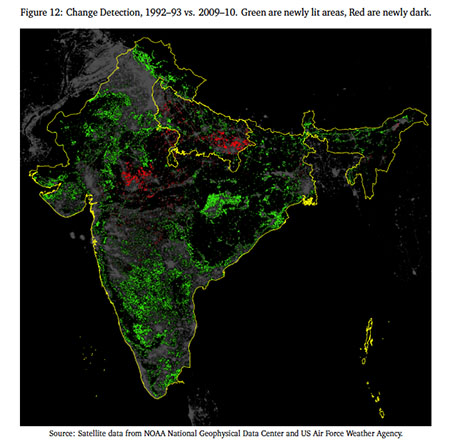

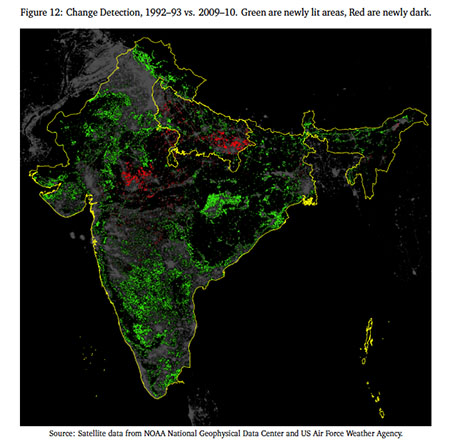

CPS researcher Brian Min developed an innovative way to track energy emissions. Min tracks images from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program’s Operational Linescan System (DMSP-OLS). In orbit since 1970, these satellites record high resolution images of light on Earth every night. Min uses these images to track energy consumption over time.

CPS researcher Brian Min developed an innovative way to track energy emissions. Min tracks images from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program’s Operational Linescan System (DMSP-OLS). In orbit since 1970, these satellites record high resolution images of light on Earth every night. Min uses these images to track energy consumption over time.

In a recent paper, Min applied this methodology to elections in India. Some of the country remains isolated from a consistent supply of electricity. Using data from 1992 to 2010, Min finds that otherwise dark villages are often illuminated during election cycles. When elections come around, politicians promise light and often deliver power leading up to votes. These areas are then returned to darkness as election promises literally fade from the spotlight.

It remains to be seen if the 2014 election will change power grids. Min will be ready to measure using the satellite images. Look out for future posts about Min’s state-of-the-art research based on the same satellite imaging in other areas.

May 8, 2014 | ANES, Current Events, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ashley Jardina.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

This month, Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy made headlines. What started as a battle against the U.S. Federal Government for his cattle and land turned into daily press conferences. As part of the Sovereign Movement, Bundy used the attention to propagate an anti-government agenda and racist ideas. Across the country at Princeton University, freshman Tal Fortgang also made headlines with his essay, “Checking my Privilege.” His championing of white privilege garnered backlash in the press. What do Bundy and Fortgang have in common? Both demonstrate reactions to a perceived status threat to whites.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) affiliate and Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan Ashley Jardina studies white identification. In particular, she argues that threats to dominant status make racial identity salient. Does this in turn influence support for political policies that could eliminate such status threats?

To answer this question, Jardina analyzed data from the American National Election Studies (ANES). Especially relevant is a measure of racial identity importance available for the first time in the 2012 ANES. This measure let Jardina gauge the extent to which white Americans feel that being white is important to their identity. She looks at whether this white identity relates attitudes toward policies (e.g., immigration) and candidates (e.g., Barack Obama) that exacerbate threats to white dominance. Immigration especially threatens whites’ dominance, because it drives demographic changes whereby whites are being displaced as the majority racial group in the nation. Likewise, as the country’s first African American president, Obama also represents a status threat.

Previous work has argued that out-group attitudes, either toward Hispanics or blacks, primarily drive whites’ attitudes toward immigration policy and support for Obama. But Jardina constructs models to explicitly test the relationship between in-group / out-group feelings. She finds in-group identity to be a more powerful and consistent predictor of restrictive immigration policies than out-group attitudes, including evaluations of Hispanics. Furthermore, whites who identified with their racial group were significantly less likely to vote for Obama, even after controlling for racial prejudice or resentment. Her results are replicated using two other datasets. Jardina concludes, “These results lend support for the notion that, in some important cases, a desire to protect the in-group, rather than dislike for the out-group, primarily drives opinion.”

Ashley Jardina will join Duke University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Political Science.