Apr 29, 2014 | ANES, ANES 65th Anniversary

Post Developed by Lynn Vavreck and Katie Brown.

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).

In this post, we consider the impact of ANES on a seminal work in the field, Lynn Vavreck’s The Message Matters.

Lynn Vavreck is a Professor of Political Science and Communication Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Her book, The Message Matters: The Economy and Presidential Campaigns, considers the role of the economy and candidate’s reactions to the economy in determining election outcomes.

Vavreck supports this idea by analyzing six decades of elections. She considers why, when, and how campaign messages matter. The election data came from the American National Election Studies (ANES), underscoring the utility of time series data. Vavreck writes of her experience writing the book…

Without the ANES, I never could have written The Message Matters, which essentially treated each presidential candidate over the last 17 elections as an observation. With only 34 cases to work with, I leveraged the power of the tens of thousands of cases the ANES offered over that same time period to test implications of my work among voters. Because of these data, I was able to show that the things presidential candidates talk about in their campaigns affect voters in predictable and important ways. Quite apart from being irrelevant, presidential campaigns play an important role in election outcomes.

Using ANES data, Vavreck concludes that the economy is the single most important feature of elections since 1950, affirming prior research in the field. The Message Matters goes one step farther, demonstrating that it is against the economic backdrop that candidates must cast themselves. The messages they promote matter. In particular, how they speak about the economy matters. And how they speak about other issues matters, particularly as it affects room for discourse about the economy.

The Message Matters garnered critical praise upon its release. Paul M. Sniderman, Professor of Public Policy and Political Science at Stanford University, writes, “I have not read a book of comparable elegance of argument and mastery of analysis in years. It is outstanding on three dimensions. In its combination of analytical depth and economy, it is a model for research on election campaigns. In its fusion of theory and empirics, it is a model for research in political science. In its principled, persistent, ingenious efforts to turn up evidence against its own hypotheses, it is a model for the social sciences.” Larry M. Bartels, Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt, raves, “Vavreck’s creative theorizing and informative historical analysis will change the way political scientists think about presidential campaigns. While giving campaign strategists their overdue due, she also sheds invaluable light on how political contexts shape their strategies and their odds of success.” Campaign consultant and pollster Stanley Greenberg declared the book “a must read” for future presidential candidates.

In sum, Vavreck’s important book was made possible in part by the time series data provided by ANES.

Apr 23, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Arun Agrawal.

This semester, the University of Michigan’s College of Literature, Science, and Arts is sponsoring a theme semester: India in the World. India was selected as a focus for many reasons: its vibrant economy, its middle class is the world’s largest, and its government is the world’s largest democracy. The theme semester seeks to “emphasize the ways that India is a part of everyday life in our increasingly globalized world.”

In this post, we celebrate both the theme semester and yesterday’s Earth Day by featuring the work of Center for Political Studies Faculty Associate and School of Natural Resources and Environment Professor Arun Agrawal. Agrawal studies environmental policy. A recent article in Environmental Science and Policy by Agrawal, Daniel G. Brown, Gautam Rao, Rick Riolo, Derek T. Robinson, and Michael Bommarito focuses on research in India to help us understand how we can use networks to curb resource use.

Research usually focuses on formal institutions as being the difference between successful and unsuccessful resource allocation. But Agrawal and his colleagues argue that institutions are only important in the context of informal networks, or the social interactions between neighbors. Networks are a pervasive part of life. They also change rapidly. But they are little studied in the context of natural resources.

Agrawal and his colleagues examine how institutions and networks interact to influence natural resource use. The authors conducted extensive fieldwork in northern India to investigate how firewood harvesting was influenced by organizations and local social networks. Firewood is critical for cooking food in India so is an important resource to study.

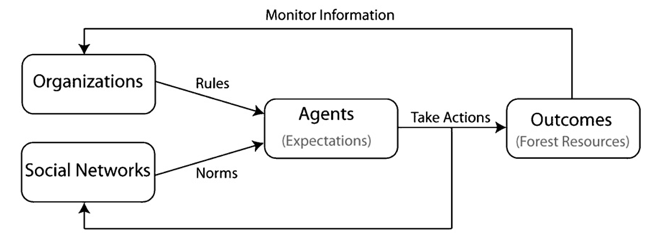

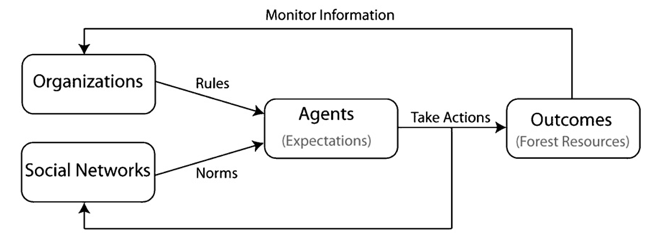

Individual Agents and Social Networks

The authors created the above model to consider changes in behaviors and changes over time. Their focus was on how people make decisions – in particular, on the amount of firewood to harvest from the forest. The changes in these decisions are affected by both institutions and networks.

Based on the results of their modeling work, the authors conclude that effective organizations leverage existing social networks. Specifically, they build on existing norms and interactions to change resource use. If institutions make small investments in changing norms, this can have a disproportionately positive impact in reducing resource use, because network interactions amplify the changes across people. That is, small changes in social networks can translate into large savings in resource use.

Connecting back to the theme semester of India in the World, Agrawal’s research in northern India holds intriguing lessons for how policy making can lead to more sustainable resource use practices: institutional changes should build on local social network effects.

Apr 16, 2014 | ANES, Current Events, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Timothy Ryan

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Partisanship gets in the way of political progress. Hillary Clinton made this common claim last week. The lack of compromise inherent to partisanship is worth investigating. What causes such non-cooperation?

Timothy Ryan, a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Michigan’s Department of Political Science and affiliate of the Center for Political Studies (CPS), seeks to answer this question. In a paper presented at the 2013 meeting of the American Political Science Association – “No Compromise: Political Consequences of Moralized Attitudes” – Ryan ran four studies to understand non-cooperation.

Ryan’s overarching hypothesis boils non-compromise down to morals: a moral mindset orients citizens to oppose political compromises and punish compromising politicians. There are all kinds of issues for which some citizens seem resistant to compromises: tax reform, same-sex marriage, collective bargaining, etc. But who is resistant? Ryan shows that part of the answer has to do with who sees these issues through a moral lens.

Ryan tests moral conviction’s effect on compromise. Data come from the American National Elections Studies (ANES), as well as surveys of undergraduates, participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, and citizens found via GfK Research (his work was made possible by a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF)). Ryan also considers several types of compromises: hypothetical, actual, positions citizens want their elected officials to adopt, and a willingness to accept a monetary reward only if a disliked group (the Tea Party or the Progressive Change Campaign Committee) also receives a donation.

Participants with moral conviction around an issue are less likely to compromise. Hypothetical and real world compromises were hindered. Compromising politicians received less support. Personal gain was sacrificed to avoid the gain of the Tea Party (if a political adversary). As Ryan concludes, “Different attitude characteristics relate to compromise in different ways, with moral conviction being a particularly potent obstacle to compromise.”

In the fall, Ryan will continue his work on morality when he joins the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as Assistant Professor of Political Science.

Apr 9, 2014 | Current Events, Elections, Innovative Methodology, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Timothy Ryan.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

There are political issues and then there are moral political issues. Often cited examples of the latter include abortion and same sex marriage. But what makes a political issue moral?

Timothy Ryan, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Political Science and affiliate of the Center for Political Studies (CPS), explored this question in a recent article in The Journal of Politics. An extensive literature already asserts a moral vs. not moral issue distinction. Yet, there is no consensus in how to distinguish between moral and non-moral political issues. Further, trying to sort issues into these categories proves challenging. Many people assume that same-sex marriage is a moral issue, but does everyone see the issue in moral terms? Do people vary in terms of whether they see economic issues, such as Social Security reform and collective bargaining, with morality at stake?

In an attempt to define the divide between moral and non-moral, Ryan turned to the psychology literature. In particular, Ryan applies moral conviction to morality in politics. Moral conviction refers to topics that tap into an individual’s sense of right and wrong. According to the psychology literature, moral conviction leads to a different type of information processing. Moral conviction involves negative emotions, hostile opinions, and potential punitive actions.

Ryan then tests this concept as it relates to political issues with two studies. In both studies, he measures the emotions stimulated by moral conviction. He finds that moral conviction evokes negative emotions toward political disagreement. He also finds that both traditionally moral issues (like abortion or same sex marriage) and traditionally non-moral issues (like labor relations or Social Security) can both illicit moral conviction.

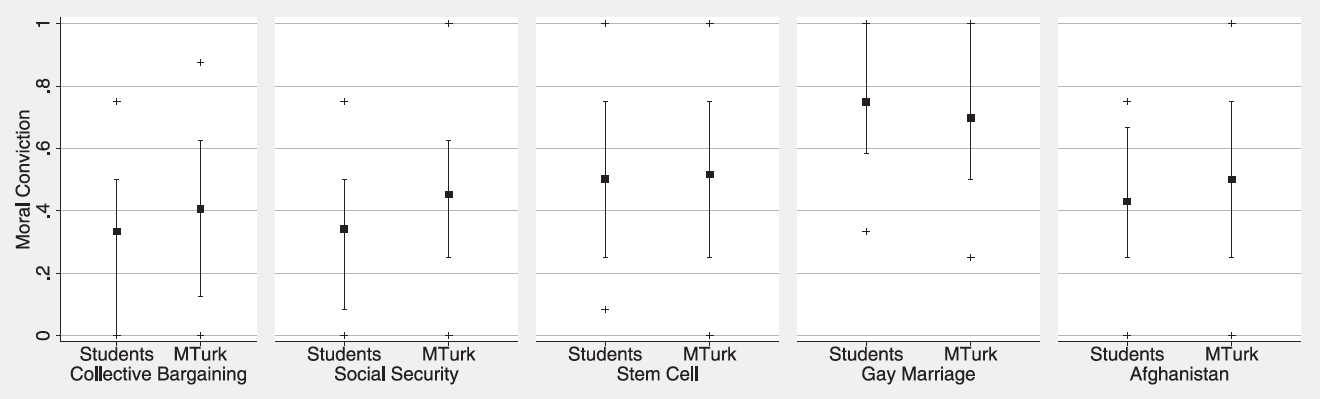

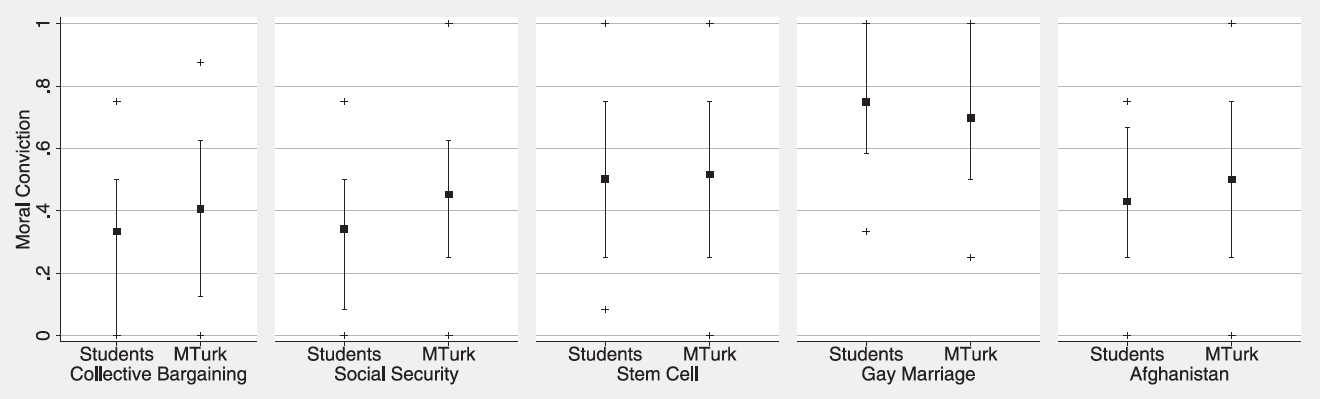

The graph below displays the mean (the squares), the middle 50% (the bars), and the middle 80% (the dots) of moral conviction for five different political issues. As we can see, moral conviction varies a lot for both economic and non-economic issues. Of course many people see same-sex marriage as a matter of right and wrong, Yet, many also see Social Security reform in the same way. The upshot is that, when it comes to deciding which issues are moral, an important part of the answer depends on the individual.

Distribution of Moral Conviction Variable

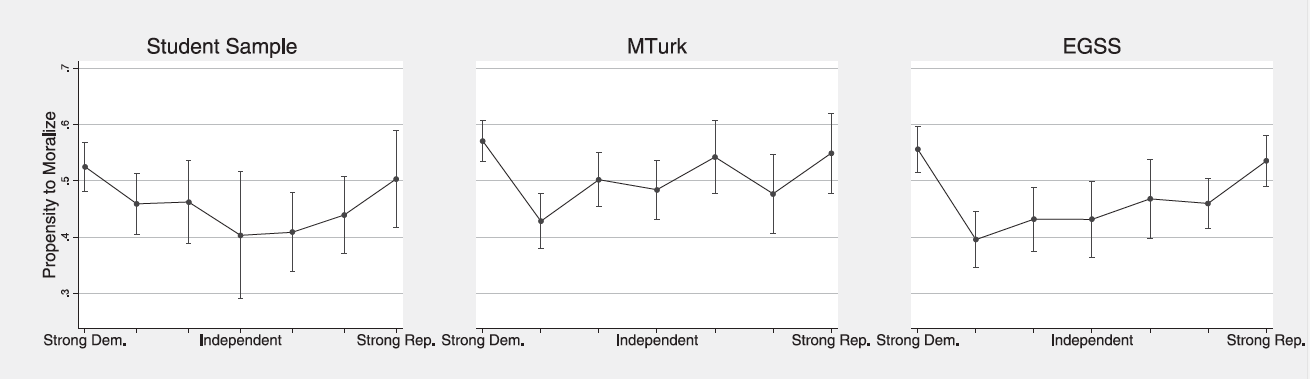

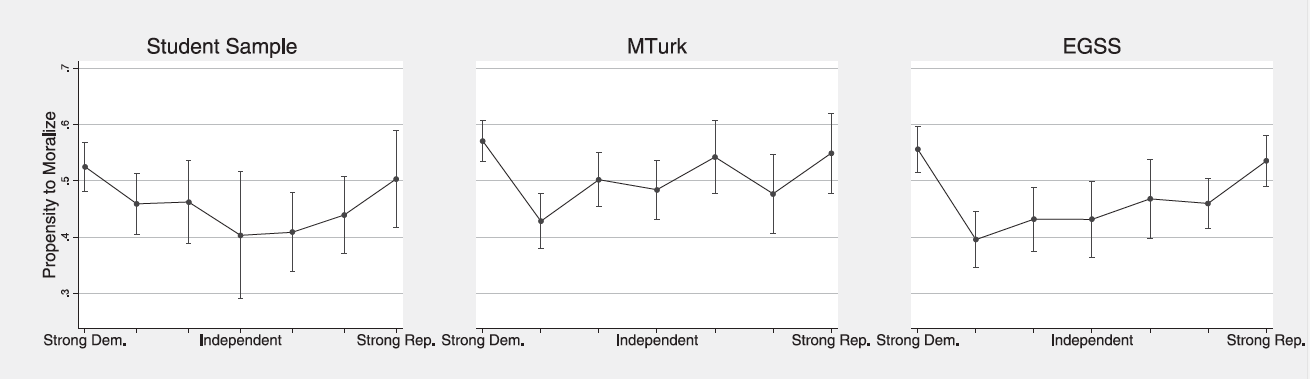

Ryan’s article also challenges a common assumption: the assumption that moral fervor in politics comes more from the right than the left. In the article, he examines propensity to moralize several political issues. The result? Liberals and conservatives moralize in equal measure. The figure below illustrates this with three separate samples: students, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk respondents, and Evaluations of Government and Society Study (EGSS) respondents.

Moral Conviction by Partisanship

Taken together, Ryan’s findings suggest that the response of moral conviction may be more important than distinguishing between inherently moral and non-moral political issues. Rather, all issues can produce a moral conviction response, depending on the person. Ryan concludes that, “in terms of the underlying psychology, Social Security is just as moralized for some people as Abortion is. Morality is in the eye of the beholder.”

In the fall, Ryan will continue his research on morality in politics when he joins the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as Assistant Professor of Political Science.

Apr 8, 2014 | Current Events, International, Law

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Yuen Yuen Ang.

The fairness of China’s court system made the news this week. Apple supplier Knowles, which makes microphones and hearing-aid pieces for iPhones, asserted it was blocked from testifying in a trial with a rival of Apple. How can we understand this?

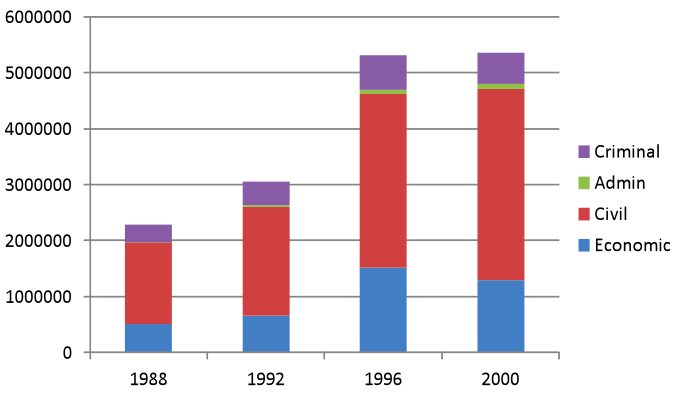

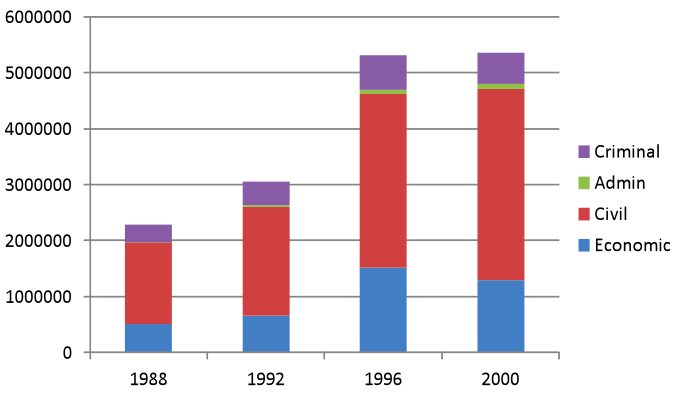

Court cases are on the rise in China, with the number of commercial cases growing steadily, second only to civil disputes. The expansion of courts should mean the rise of the rule of law and a more level playing field for firms, right? Not exactly.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate, assistant professor of political science, and Center for Chinese Studies faculty associate Yuen Yuen Ang studies this trend. In a recent article, forthcoming in The Journal of Politics, Ang and Nan Jia find that politically connected firms are actually more likely to use courts than non-connected firms. These connected firms are congressional delegates and/or former party-state officials.

Political connections among private firms in China shape not only their access to resources and profitability, but even their willingness to use courts for dispute resolution.

Number of Court Cases by Type over Time

However, the fact that politically connected firms use courts more may not signal the subversion of law. Besides having access to officeholders (“know who”), politically connected firms also tend to have more knowledge about and confidence in navigating the legal system (“know how”). So do politically connected firms use courts more because of “know who” or “know how?”

By analyzing survey data of over 3,900 private firms in China, Ang and Jia finds that “know who” dominates “know how” in inducing politically connected firms to use courts more.

Findings from the study challenge the assumption in Western-based theories that as law and courts expand, connections will diminish in influence. As the authors write:

“The substitutive view of formal laws and informal networks is premised on the substantial passage of time and absence of a strong authoritarian state in legal development. The edifices of law can be quickly built, but one cannot assume that norms and practices of impartiality will follow, particularly when courts are subordinated to politics by design. In institutional landscapes such as those of China, we can expect a fusion of legality with politics and the informal with the formal.”

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).