Jan 23, 2024 | Economics, National, Policy, Race

Information about the wealth gap between Blacks and whites increases Americans’ awareness of disparity, but does little to increase their support for affirmative action, reparations

Since the “racial reckoning” of 2020, Americans have become increasingly aware of the barriers Black people face to accessing economic opportunities and achieving intergenerational mobility.

But despite widespread knowledge that racial inequality exists, even among liberal, white Americans, the public is radically uninformed about the depths of one of the most profound racial disparities: the racial wealth gap.

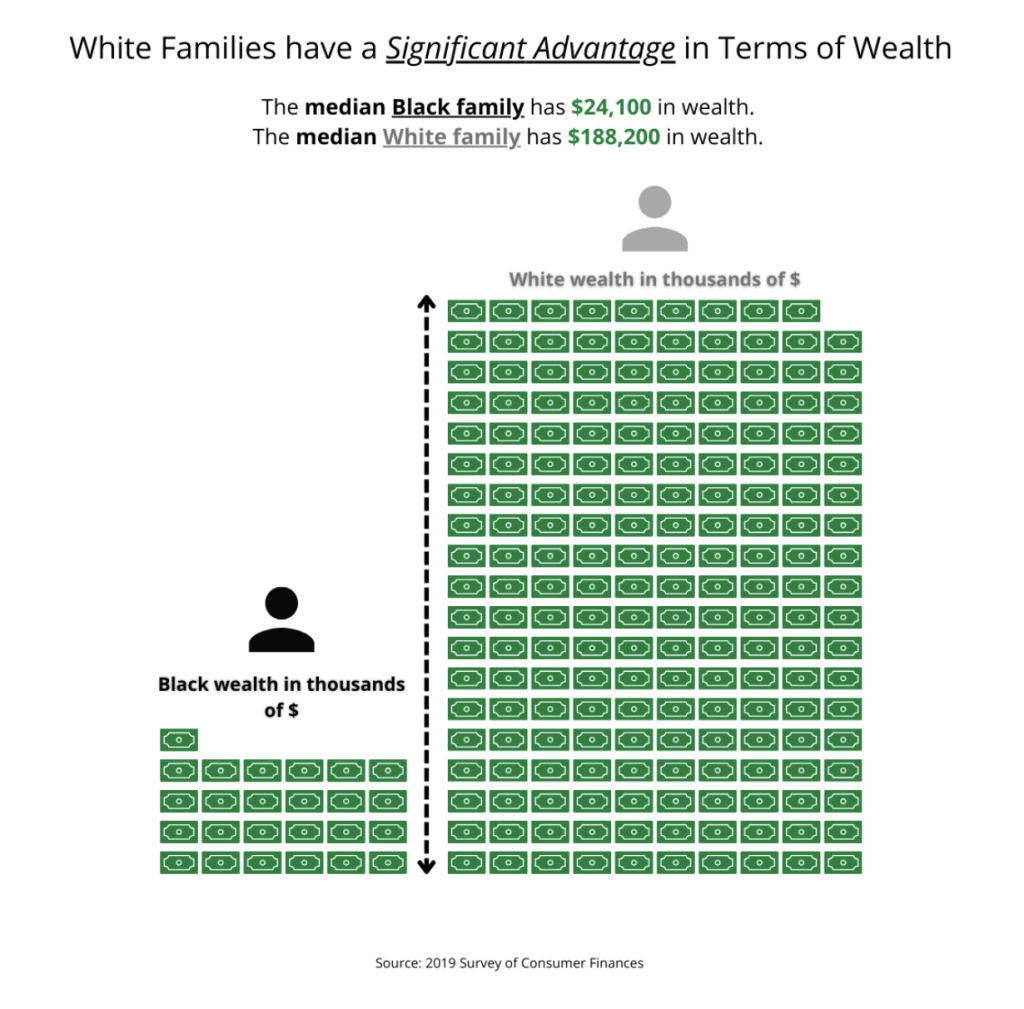

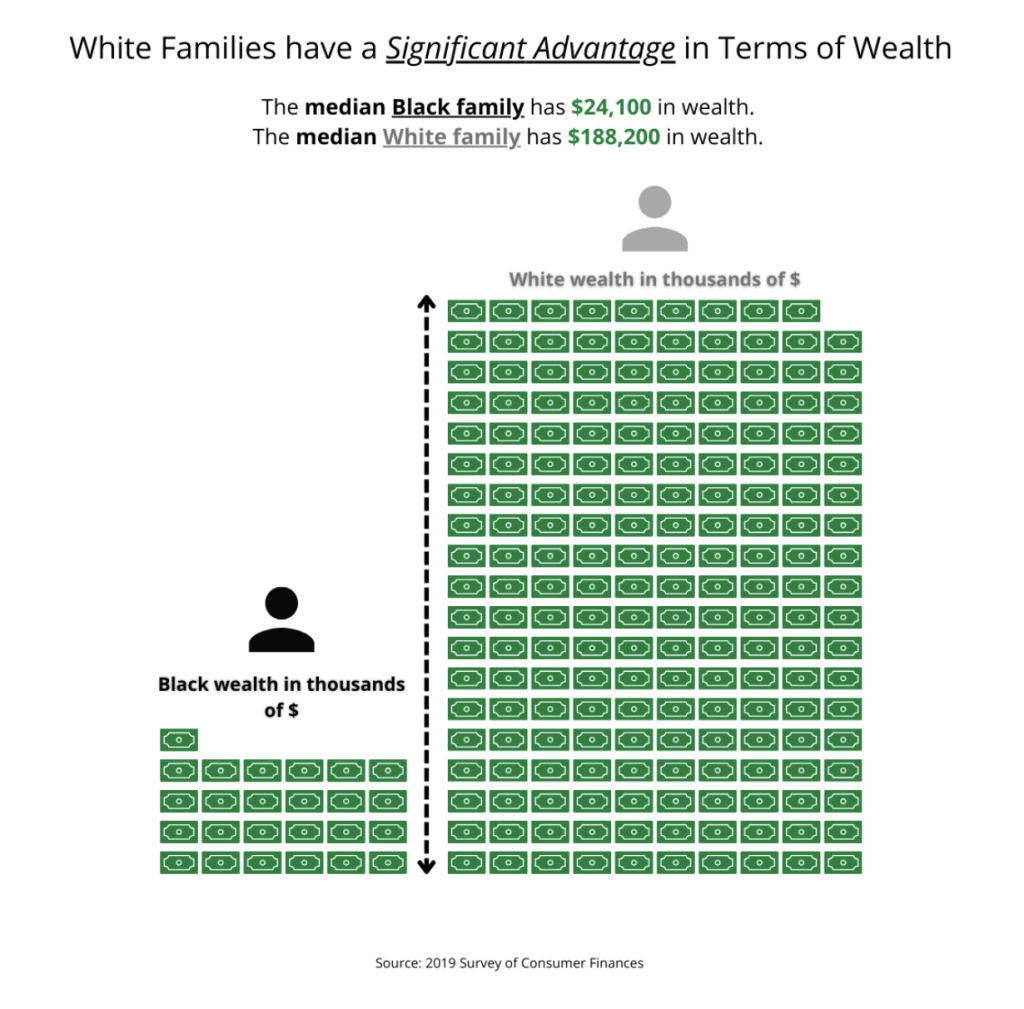

According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, which collects nationally representative data on American households, the median white family has about 8 times more wealth (that is, total assets minus total debts) than the median Black family. And, despite popular perceptions of education as the vehicle for eliminating racial disparities, education does little to diminish the gap between Blacks and whites. The median white family where the household head did not finish high school has virtually the same wealth as the median Black family where the household head earned a bachelor’s degree. In other words, a Black American has to graduate from college to access the same level of wealth as a white high school dropout.

If you find these numbers startling and even difficult to believe, you are not alone.

Since 2020, my research team, which includes Vincent Hutchings, Kamri Hudgins, and Sydney Carr, has been learning what happens when we correct misperceptions of the racial wealth gap. Does informing people about the size of the racial wealth gap influence opinions about policies to address the gap? How does the public react to information about the racial wealth gap?

Using a novel survey experiment fielded on three nationally diverse samples, we found that exposing both Black and white Americans to information about the size of the racial wealth gap increases their awareness of this disparity– but exposure to this information does little to increase their support for race-targeted social and economic policies like affirmative action and reparations.

For example, among white participants, exposure to our racial wealth gap information treatment increased awareness of the size and severity of the racial wealth gap by, on average, 7 to 18% across the two studies. However, exposure to the same information did not significantly increase support for race-targeted policy changes to reduce the racial wealth gap among white or Black participants.

In contrast, our treatments did increase support for race-neutral equity policies like baby bonds, a program that would fund a trust for every newborn child to establish a baseline level of wealth for all Americans. When informed that Black college graduates have the same level of wealth as white high school dropouts, both liberal and conservative white Americans’ support for baby bonds increased significantly. For conservatives, support increased by 12% moving from a baseline of .41 (indicating weak opposition) to .53 (indicating weak support). For liberals, support increased by 11% moving from .71 (strong support) to .82 (very strong support).

But economists argue that race-neutral programs like baby bonds or canceling student loan debt would not be nearly enough to close the racial wealth gap. For example, Duke University economist William Darity, Jr. proposes that only a comprehensive reparations program requiring “the full resources of the federal government” to redistribute wealth to Black Americans would be sufficient for closing the gap.

Those who believe legislative action on reparations is urgently needed will find the political momentum behind it at the federal level to be insufficient. President Joe Biden made the most progress on this issue of any president in history when he proposed a commission to study whether or not reparations should be paid to Black descendants of the enslaved. But the bill has effectively died in committee and there have been no votes on the House floor regarding the commission or any other reparations policies. While several states and localities have made more progress toward providing reparations to Black residents and, in some instances, (like Evanston, Illinois) have even begun issuing payments, these programs will not resolve the Black wealth crisis nationwide.

As this project develops, we hope to probe public opinion on other racial disparities, including the racial gap in rates of maternal mortality, and increase scholarly and public understanding of what it takes to move the public towards action on racial inequality.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

Zoe Walker is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Ford Foundation Predoctoral Fellow. Her dissertation research, supported by the Russell Sage Foundation, considers how beliefs about economic opportunity influence perceptions of racial inequality and support for racially redistributive policies among Black Americans.

Sydney Carr, Kamri Hudgins, and Zoe Walker are all Next Generation scholars of the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research and were consecutive recipients of the Hanes Walton, Jr. Endowment for Graduate Study in Racial and Ethnic Politics at the Center for Political Studies.

Hanes Walton, Jr. of the Center for Political Studies transformed the study of Black politics and helped establish it as a subfield of political science. The 2024 Hanes Walton Jr. Lecture at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research will be presented by Christian Davenport on Feb. 1.

Jan 4, 2024 | expert analysis, National, Race

After the murders of George Floyd and Breanna Taylor by the police in 2020, the United States witnessed what was arguably the largest protest movement in that nation’s history. Millions of Americans marched in protest of racist police violence and in pursuit of systemic solutions to racial inequality. Scholars have rightfully documented this moment in history, analyzing the different conversations and opinions about Black Lives Matter, racial minorities, and racialized policies. For example, some have analyzed Members of Congress’s communications to their constituents, news framing of the Black Lives Matter protests, and antiracism in sports, teaching curricula, and social media posting. Notably absent from this important set of research, though, is an understanding of how these conversations played out in what are arguably the most central institutions to the everyday lives of millions of Americans: churches.

The stakes are high for understanding the content of religious services. While the pandemic caused a decline in religious attendance, still about 40% of the American population attends a religious service at least once a month or more. The number of Americans who listen to a weekly message from a religious leader far outnumbers the fraction of Americans who watch the State of the Union, presidential debates, or the presidential inauguration. It is even more than the portion of Americans who say they follow the news “all or most of the time.” Moreover, researchers have found that both religious elites and attendance at religious services can influence a number of political attitudes and behaviors, such as electoral participation, ideology, and views towards issues such as poverty and immigration.

It matters how discussions about racism play out in religious spaces. These conversations both shape and represent how many Americans understand the origins of racism and solutions for racial inequality. In the case of the United States, many of the religious spaces where these conversations take place are Christian churches. Churches are a fruitful venue for understanding political discussion among the American public because religious services could be viewed as communication among individuals who share a common religious identity and—due to racial and political segregation among U.S. Christians—likely agree on a number of political issues.

In my doctoral work in Political Science at the University of Michigan, I have analyzed sermons delivered in historically- and majority-white U.S. Christian congregations. I find that sermons infrequently mention racism: roughly 8% of sermons in my sample mention the words “racism,” “racist,” or “racial.” I also find only small distinctions across denominations. When clergy talk about racism, it is more frequently the case that racism and its perceived solutions are understood in individualistic rather than systemic terms. However, a few sermons do discuss racism as a more systemic issue, and call for the pursuit of racial equality.

In order to examine the contours of political discussion in religious spaces, I collected a dataset of transcripts of over 260,000 videos posted on YouTube by about 1,500 U.S. Christian congregations. Many congregations—especially in response to the pandemic—post recordings of their services online. These congregations are diverse on a number of dimensions, spanning all 50 states, and the video transcripts I collected span over 10 years. While some of these videos include the entirety of the religious service, my analysis focuses on “sermon” transcripts, defined here as the portion of the service where the religious leader (i.e. pastor or priest) is speaking on a topic specific to that particular service.

I rely on text analysis of the sermon transcripts to understand how politics are discussed in religious services. Text analysis is a set of computational techniques for reading, classifying, and sorting information from written texts, often at a larger scale than what would be feasible for a researcher to read and analyze themselves. In this project, I am particularly looking at differences in the frequency and context in which the word “racism” is used. (I also include mentions of the terms “racist” and “racial,” but I will collectively refer to these terms as mentions of “racism” throughout this post.)

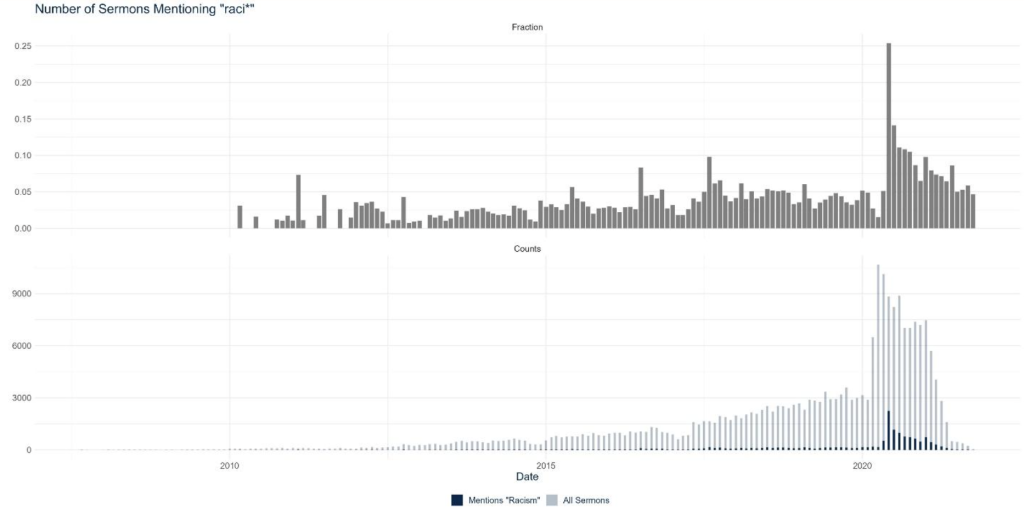

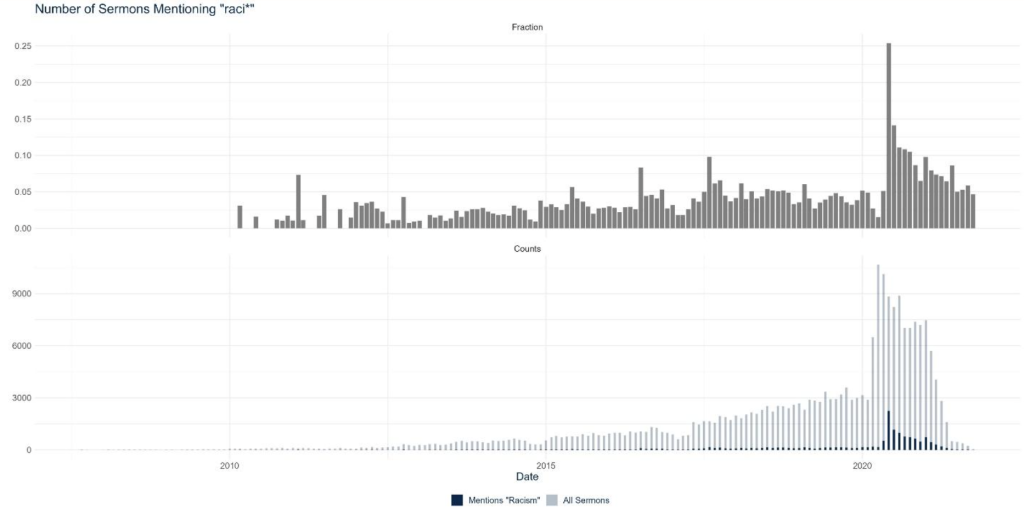

In the above figure, I plot the fraction and number of sermons that mention one of these terms. On average, about 8% of sermons mention racism. Before the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement, an average of 5% of sermons mentioned racism. However, there is a substantial increase in the number of sermons that mention racism around June 2020, where about 25% of sermons mentioned racism. In the period following, roughly 10% of sermons mention racism.

Next, I examine how clergy discuss racism through the use of word embeddings. A word embedding is a numerical representation of a word that preserves some semantic meaning. This means that words that are associated in real-world contexts are numerically closer together in their word embedding representation. An example of how political scientists have used word embeddings is to analyze how Republicans and Democrats in Congress differ in their discussions of immigration. For Republicans, the term immigration is more closely related to the term “enforce,” and for Democrats, immigration is understood more in terms of “reform.”

For my application, I am viewing word embeddings as a representation of how clergy understand the causes of and solutions to racism. I can also test whether racism is viewed as an individual or systemic concern in these messages. I find that Protestant congregations are more likely than Catholic congregations to understand racism in individualistic terms (such as “you” and “I”), and Catholic congregations are more likely than Protestant congregations to understand racism in systemic terms such as “injustice.”

Using this method of word embeddings, I can also find excerpts from the sermons that are, on average, the best representation of how racism is discussed across different denominations. The most representative example of how racism is mentioned in the non-denominational and the mainline protestant congregations in my sample is the following excerpt from a sermon delivered in a large, non-denominational congregation in August 2020:

“There are differences between us but God says those things don’t have to stay between us, and so there is a terrible hatred. If you think racism is a problem today, you’re right, but it can’t hold a candle to the level of racism that was present between Jew and Gentile.”

For evangelical congregations, the most representative example comes from a sermon delivered in June 2020, in a medium-sized evangelical church:

“If you think about it, we would solve racism in America in one generation if we would have Christ-centered homes. We would, racism just wouldn’t exist in our country anymore largely. So let’s pray for healing in our country. Father God, we lift up our country to you and the people in our country, our leaders Lord, our police officers, and our African-American brothers and sisters…”

These examples support arguments among scholars that many white Christians have difficulty acknowledging racism as a system of inequality and injustice because individualism is emphasized as a theological commitment. W.E.B. DuBois viewed religion as integral to U.S. race relations. Indeed, the Black church has long been viewed as a central institution for providing civic resources to its congregants. However, DuBois aptly viewed the white church as a space where white supremacy is nurtured, by reimagining our nation’s legacy of racism or by ignoring the issue altogether.

However, my research agenda is concerned not only with diagnosing the ways in which religion in white Christian contexts can perpetuate racial injustice, but also how it may play a crucial part in motivating congregants to pursue justice. Another example from the sermons—a prayer delivered in a Catholic mass in January 2021—demonstrates a more collective, action-based discussion of racism:

“Christ freed humanity from its slavery to darkness. May Christian communities deepen their commitment to racial equality and racism out of love for the one God and Creator of all, we pray to the Lord. Lord hear our prayer.”

While Catholic congregations in my data were more likely to discuss racism in systemic terms than Protestant congregations, there is evidence across all traditions of both individual and systemic understandings of racism. Documenting these discussions is important for gaining a better understanding of how Americans understand and engage with questions of racial justice.

In other research projects, I argue that religious identity is actually a crucial component of white Christians’ racial attitudes. If religion is an important factor in how a large portion of Americans understand U.S. racial politics, then perhaps we can also look to religion to understand how to build support for policies seeking to remedy racial equality.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

Shayla Olson is a PhD student of American Politics and Quantitative Methods in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan. Her broad research interests fit within the fields of American political behavior and public opinion, with a focus on the intersection of race and religion in the United States. She is particularly interested in how local church contexts and clergy communication influence political and racial attitudes. A Next Generation scholar of the Institute for Social Research, Shayla Olson is the recipient of the Hanes Walton Jr. Endowment for Graduate Study in Racial and Ethnic Politics at the Center for Political Studies.

Hanes Walton, Jr. of the Center for Political Studies transformed the study of Black politics and helped establish it as a subfield of political science. The 2024 Hanes Walton Jr. Lecture at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research will be presented by Christian Davenport on Feb. 1.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Shayla Olson; CPS staff member Tevah Platt contributed to its development.