Making Education Work for the Poor: The Potential of Children’s Savings Accounts

Post written by Katherine Pearson

Dr. William Elliott contends that we need a revolution in the way we finance college education. His new book Making Education Work for the Poor, written with Melinda Lewis, takes a hard look at the inequalities in access to education, and how these inequalities are threatening the American dream. Elliott and Lewis present data and analyses outlining problems plaguing the system of student loans, while also proposing children’s savings accounts as a robust solution to rising college costs, skyrocketing debt burdens, and growing wealth inequality. In a presentation at the University of Michigan on October 3, 2018, Elliott presented new research supporting the case for children’s savings accounts and rewards card programs.

This video of Elliott’s talk was recorded by Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan.

There is a prevailing belief that education provides a path to success and greater income. However, Elliott points out that income provides a means to survive, whereas assets determine who will thrive. Our current educational financing system, which relies mainly on student loans, may help some students reach higher income levels, but it does not equalize the wealth gap. In fact, the high debt burden of student loans actually widens that gap.

Defining the Problem

College access is more than a matter of having enough money to pay for a college education. Elliott asks a different question: are you better off going to college than not going? And does college pay off equally whether or not you graduate with debt.

Student loans have become the dominant means to finance a college education. In 2000, student loans made up 38% of net tuition, fees, room, and board; by 2013 they made up 50% (Greenstone, Looney, Patashnik, and Yu, 2013). Programs such as income-based repayment seem popular because they decrease loan defaults, but they actually increase debt burden by extending the length of time it takes to pay off the loan.

Data shows that assets matter

Elliott uses data to show that students who have to pay for college with student loans do not achieve the same outcomes as students who do not have to take out loans. According to the Government Accounting Office, assuming a standard ten-year payback at 7% annual interest, average cumulative undergraduate educational debt exceeded $18,000 in 2000. This means that students who take out loans pay $6,000 more in interest than their peers who did not take loans. Elliott challenges us: does this sound like equal opportunity? Furthermore, data shows that low-income students and African Americans earn less from their college degrees as adults. If education is to equalize these disparities, the return on the investment in a college a degree must be higher for all children, particularly those with low incomes and students of color.

Wealth inequality contributes to having higher amounts of student debt. Racial disparities in income and wealth account for over 35% of the black-white student loan debt in young adulthood. (Huelsman, 2015) This debt contributes to education’s failure to deliver on the opportunity to achieve the American dream. Research finds that acquiring the relatively small amount of $10,000 in student loans is associated with an 18% decrease in the rate of achieving median net worth.

In short, growing up in a family with less wealth contributes to having more student debt, and having more student debt contributes to having less wealth as a young adult creating a cycle of inequality from one generation to the next.

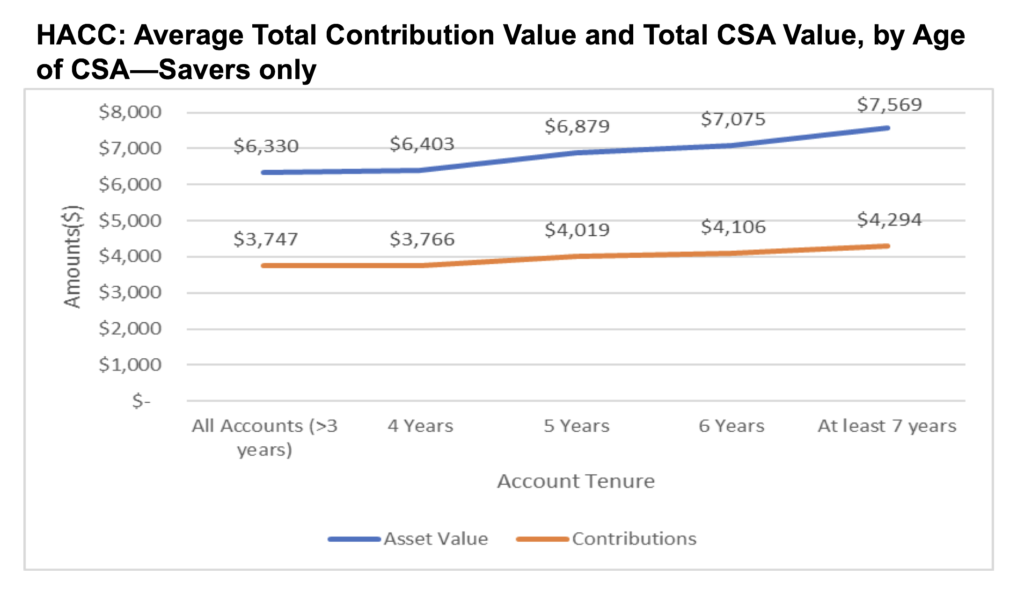

Small Dollar CSAs Build Wealth

Elliott shows that children’s savings accounts (CSA) have a positive effect on a family’s ability to save for college. However, small dollar CSAs haven’t been able to fully overcome the fact that low-income and minority families often have little money after they pay for basic needs.

The graphic above shows contribution value and total CSA value for the Harold Alfond College Challenge (HACC).

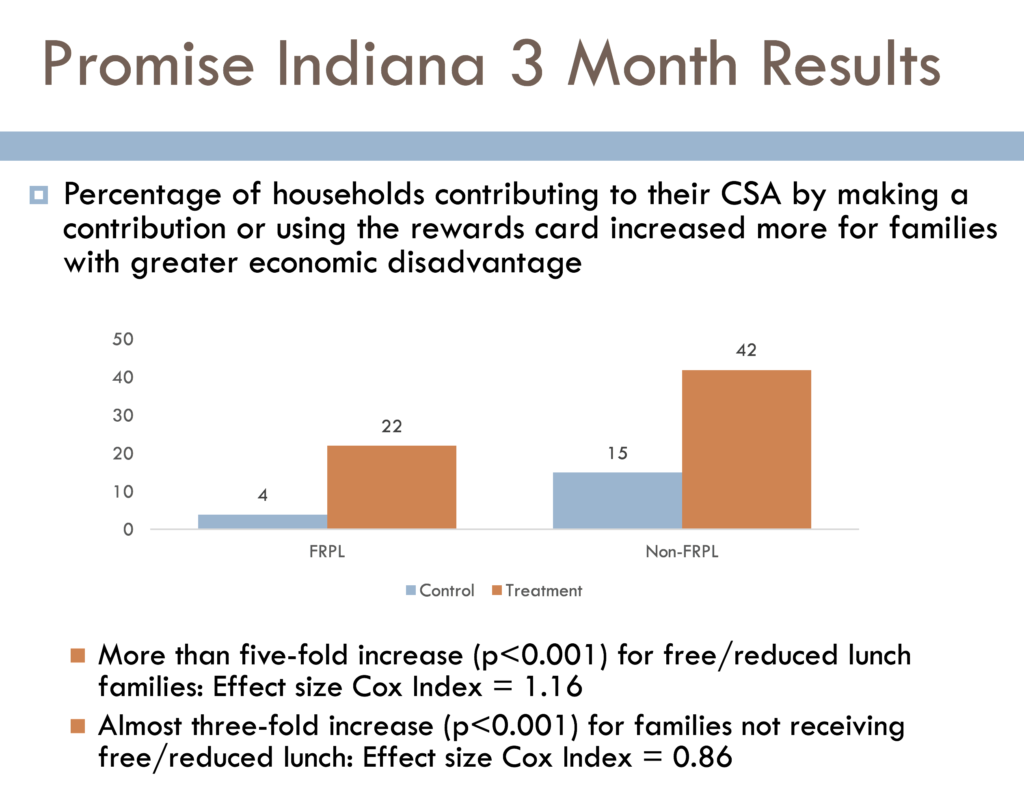

One answer to this dilemma may be rewards cards. Elliott presented data from programs set up by grocery stores that offer a percentage of their sales to CSA programs, on the expectation of increasing sales volume. This intervention transforms spending into saving. Not only are families able to save without tapping into already very limited financial resources, it shapes the children’s expectations that they will be able to go to college, and start planning for their future with a greater sense of control.

Looking forward, Elliott and fellow researchers are launching three randomized control trials of rewards card programs in Wabash County, Indiana; St. Louis, Missouri; and Lansing, Michigan. These trials will examine whether or not families will actively save for college using a rewards card, how much they are able to save, and whether or not families will make a contribution to the CSA in addition to saving with the rewards card. Already, early results show an increase in savings. The rewards cards tripled the number of households actively saving via rewards cards, and consequently increased the averaged dollars saved after only 3 months. Behavioral and financial literacy attempts have not been effective way to increase college savings among the poor because low-income people have little money to contribute regardless of their level of financial literacy. Rewards programs, on the other hand, appear to be a promising way to help low-income families participate in saving in CSAs.

An Asset Building Agenda for the 21st Century

Elliott likens CSAs to the plumbing, the most basic infrastructure, of a new system of education financing for the 21st century. Rewards cards add a new layer to that system that allows poor families to access the system of saving for college.

Creating a system where more people can build assets is a direct way to start closing the wealth gap in America. However, students with fewer assets end up paying much more for education when they can access it. Elliott argues that the idea of a wealth transfer is completely consistent with American history and with our collective narrative of individual effort. It is about equipping all children with tools that complement their own contributions. There are historical precedents for this type of wealth transfer, too: the Homestead Act and the GI Bill. Both required considerable individual effort, yet offered real promise to change the distributional consequences of existing systems—property ownership, on the one hand, and higher education, on the other—in ways that helped to transform power and pathways to prosperity, for generations. In the 21th Century there has yet to be such a wealth transfer, although the need has never been more urgent.