New Book Examines Ghana’s Political Trap

Post developed by Katherine Pearson

As a country grows and develops economically, most experts expect political behavior to develop as well, becoming more policy-oriented and programmatic and moving away from clientelism that characterizes less developed countries. However, this has not been the case in Ghana. In his new book, Electoral Politics and Africa’s Urban Transition, Noah Nathan traces the unexpected political patterns that are emerging in urban Ghana. Despite a growing middle class and increasing ethnic diversity, clientelism and ethnic voting persist in many urban neighborhoods.

Nathan focuses his research on Accra, Ghana, a diverse and growing metropolis of four million people. Not only is the population of the city growing, but it is becoming wealthier and better educated: data show that the middle class in Accra has tripled in size since Ghana democratized in 1992. The trend toward urbanization has also led to more diversity and contact between members of different ethnic groups in the city. Experts usually expect that higher incomes and levels of education will shift voter preferences away from politicians offering patronage and toward more policy-oriented candidates.

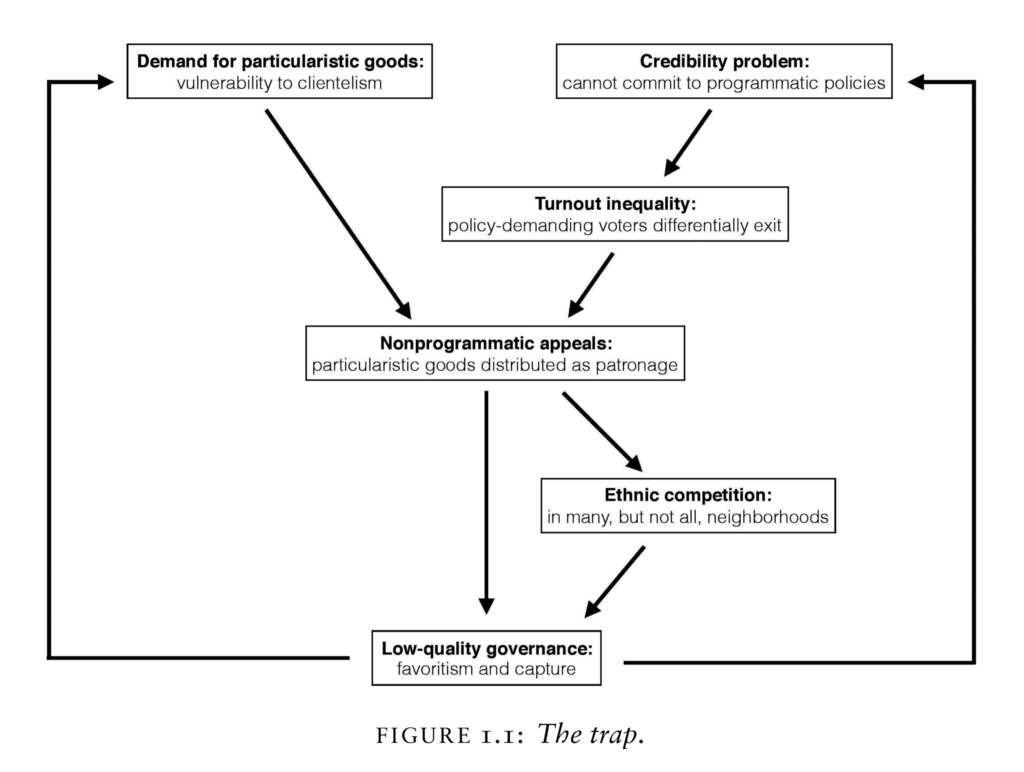

Political practices in Ghana have not transitioned as rapidly as the demographics have. Instead, Nathan shows, Ghanaian politics have become stuck in a trap. The trap is a cycle wherein voters expect goods and favors, which politicians deliver in the form of patronage. As a result, the government performs poorly and elected officials are seen as less credible. Policy-oriented citizens are left without programmatic candidates, and become more likely to decide to opt out of voting entirely. With those voters increasingly out of play, politicians face strong incentives to continue engaging in clientelism, sometimes creating ethnic competition.

Nathan, Noah L. Electoral Politics and Africa’s Urban Transition: Class and Ethnicity in Ghana. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

The key to understanding the political trap of clientelism is the neighborhood-level variations within cities. Voters with similar levels of wealth and education do not all vote alike across the city; voting behaviors differ greatly by neighborhood. Voters in poorer neighborhoods still expect favors from politicians, who respond accordingly. Taking this into account, many middle-class voters, those who are most likely to support a programmatic transition, opt out of voting because they view politicians engaging in patronage as lacking credibility.

Certain features of developing cities give further context to explain politicians’ and voters’ incentives. Developing countries have lower capacity to provide services and infrastructure to their citizens as a whole. The rapid pace of growth creates a scarcity of resources to go around. Without the credibility to promise broad improvements, politicians rely instead on promises to select groups. Cities tend to be comprised of neighborhoods that differ widely in their wealth and diversity, often within the same electoral district. Understanding these realities help explain why clientelism prevails, even as the electorate becomes wealthier, better-educated, and more diverse.

Nathan concludes his analysis of the political patterns in Ghana by drawing parallels with political systems seen in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, as well as in Latin American cities. In these cases the shift to more programmatic politics occurred politicians could no longer distribute government resources selectively. The rise of civil service reforms and broad social welfare programs supported the shift to policy-oriented systems. These parallels to similar transitions over time and in other developing countries may point the way to more policy-oriented political systems in the future.