Jul 2, 2024 | ANES, ANES 75th Anniversary

One of the early discoveries of the founders of the American National Election Studies (ANES) was that psychological attachments to parties themselves are group identities: Americans often vote as their parents did, and maintain allegiance to parties over time.

The ANES has surveyed Americans before and after every U.S. presidential election since 1948, providing us with rich insights into why and how Americans vote. In recognition of the ANES’s 75th anniversary, the Center for Political Studies reached out to scholars to ask what we know about American politics, voters and voting behaviors because of the ANES. This is what they told us:

“In numerous publications (for a summary see Sears & Funk, 1991) we have used it to challenge the idea that self-interest is a pervasive motive, rather than an occasional exception, in Americans’ voting decisions.”

– David O. Sears, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, UCLA

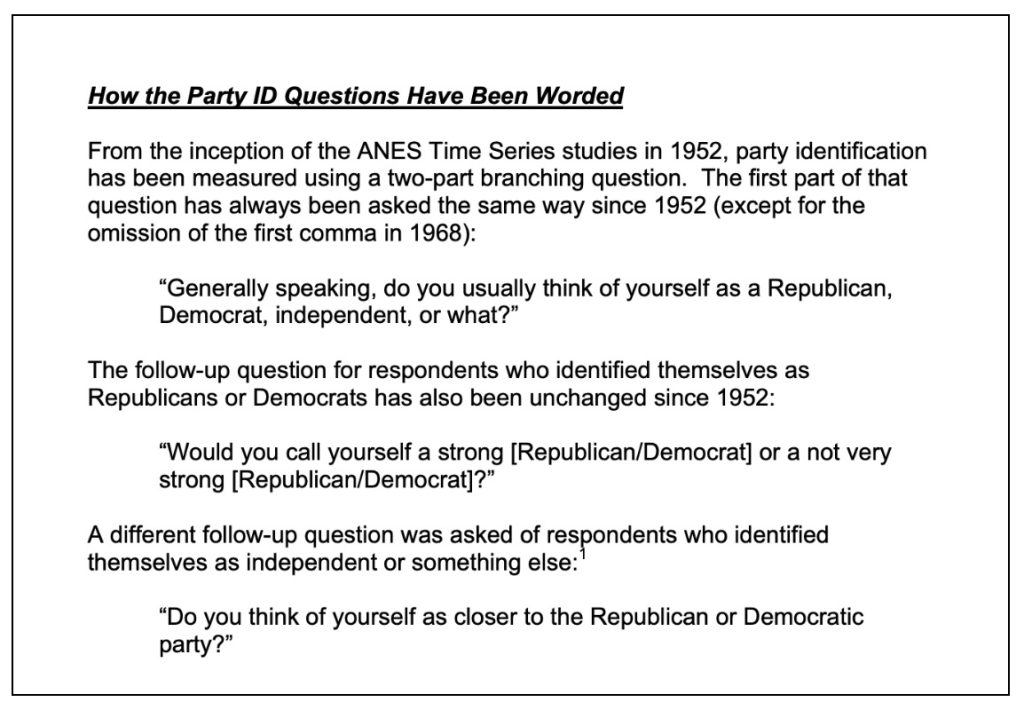

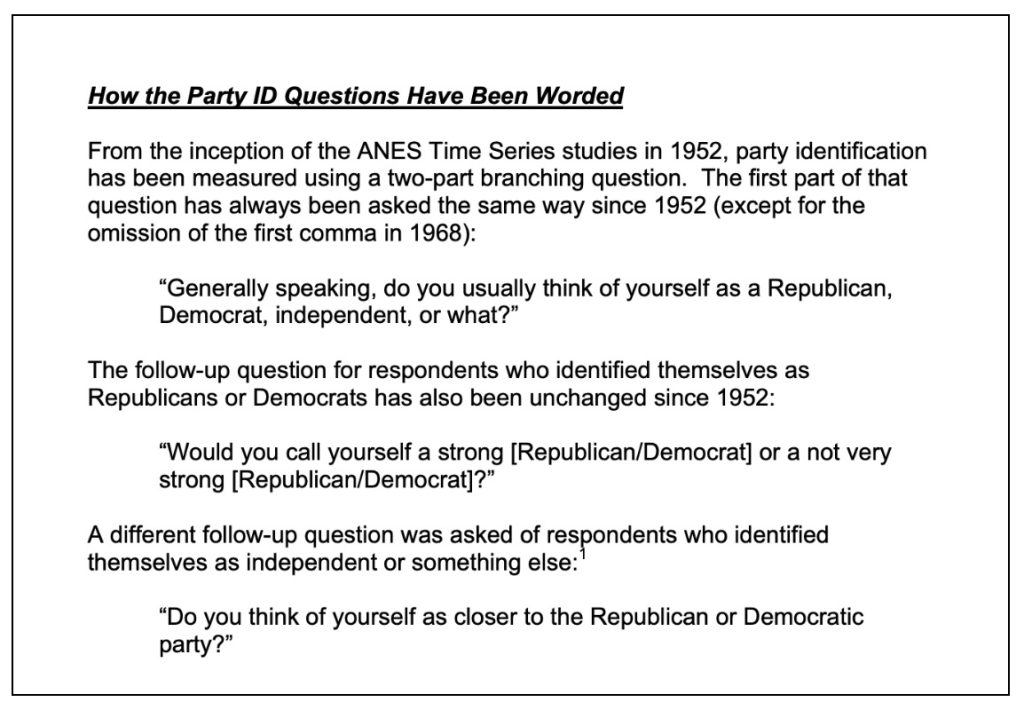

“The ANES is one of the earliest surveys of the American public. Much of the research on partisanship, for example, emerges directly from the way that the ANES asks people about their party identification. Concepts like a ‘leaning independent’ – someone who identifies as an independent but ‘leans’ toward one of the two parties– largely exist because of the ANES. Given the importance of partisanship to political behavior, the ANES is really the first step in our understanding of how people come to feel a connection to a party.”

– Yanna Krupnikov, Professor of Communication and Media, University of Michigan; Faculty Affiliate, Center for Political Studies

“As a scholar of race and politics, one of the most useful aspects of the ANES is that it allows us to track racial attitudes and their relationship with political outcomes over time. For example, we can observe the ebb and flow of racial resentment among white Americans, while also investigating the changing political significance of more explicit racial attitudes. In more recent years, the ANES has allowed for the careful study of white identity and its relationship to some of the most consequential political outcomes of our time, including white Americans’ support for Donald Trump. There is no doubt that the ANES will remain a vital tool for generations of scholars to come.”

– Hakeem Jefferson, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Stanford University

“The contemporary study of American public opinion and elections rests on the foundation of research from the earliest ANES studies, represented in highly influential publications such as The American Voter (Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes 1960), Elections and the Political Order (Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes 1967), and “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics,” (Converse, 1964). Scholars today continue to work with many of the concepts, measures, and ideas introduced in those early studies. Because of the breadth and depth of the survey instrument, the quality of the sample, and the power of the pre-post design, the ANES has throughout its history been the most important source of data for understanding the results of any single Presidential election. Because the ANES has made continuity in the survey instrument a priority, the data have also been invaluable for identifying and explaining how public opinion and voting behavior have changed over time. Scholars have used the data to make inter-election comparisons (e.g., support for Trump in 2016 vs. 2020, dynamics in the Obama elections compared to before or after) as well as longer-term comparisons (e.g., in the size of voting gaps by party, gender, race, and place; in levels of affective polarization, partisan defection, independent identification, voter turnout, and political trust). At the same time, the ANES has continued to innovate and respond to new political contexts in developing its questionnaires, fueling new research agendas. For example, the most recent study included new questions regarding populism, racial and policy attitudes, electoral integrity, social media use, and rural resentment.”

– Laura Stoker, Professor of the Graduate School in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley, Emerita

“Looking back over the decades, it’s worth noting the enormous intellectual progress that the ANES participated in and helped to generate—when you’re low on the learning curve progress is rapid. Many ideas that are imparted to undergraduates in Survey Research 101 today were being discovered or becoming appreciated in the early 80s. I remember Don Kinder bringing in a paper to a Board meeting showing the different responses obtained by framing survey items in different ways. Priming respondents to think along various lines, question order, the importance of response formats—ideas that are taken for granted today—were brought into mainstream Political Science by the activities of the ANES.”

– Morris P. Fiorina, the Wendt Family Professor of Political Science and a Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution

“The contributions of the ANES data sets to the understanding of American politics, particularly voting behavior and public opinion, are beyond counting at this point. But to my mind, the greatest is the opportunity they provide for scholars to trace and explore both the continuities and profound changes in mass political attitudes and behavior over the past 75 years. In my primary research domain of congressional elections, the world of the 2020s looks vastly different from the world of the 1960s and 1970s. The time series studies have documented key changes in real time (as measured in election years), and as new developments have raised new questions, being able to go back and reconsider old data in a new light has been invaluable for anyone trying to figure out what has happened. A good example is how the time series has revealed the growing coincidence of ideology, policy preferences, religiosity, and demography (race, gender, age, and education) with partisanship, trends that have made the party coalitions increasingly homogeneous internally and distant from one another. If you are looking to explore the causes and consequences of the polarized partisanship that now plagues us, this is an excellent place to start.”

–Gary Jacobson, Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Political Science, UC San Diego

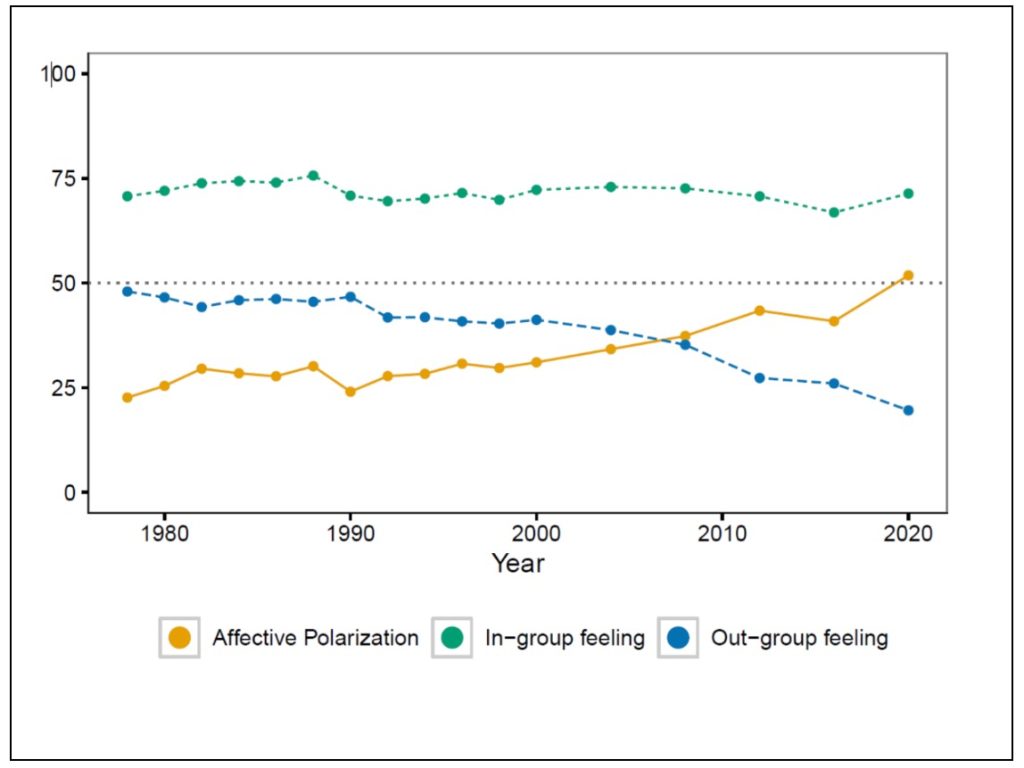

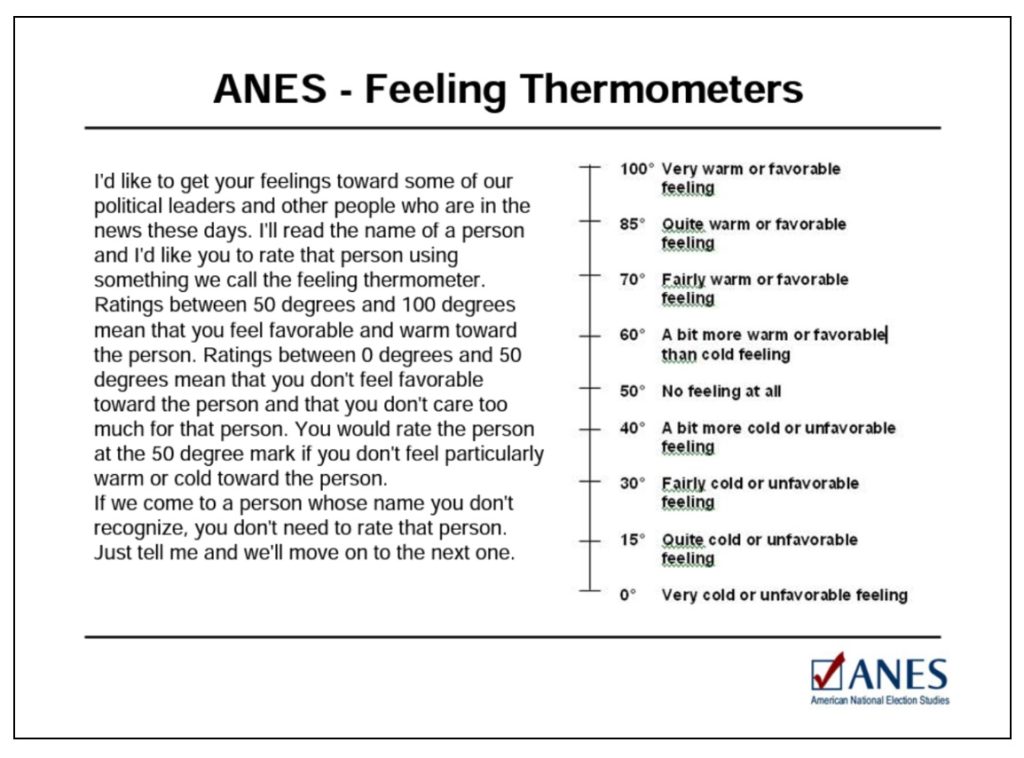

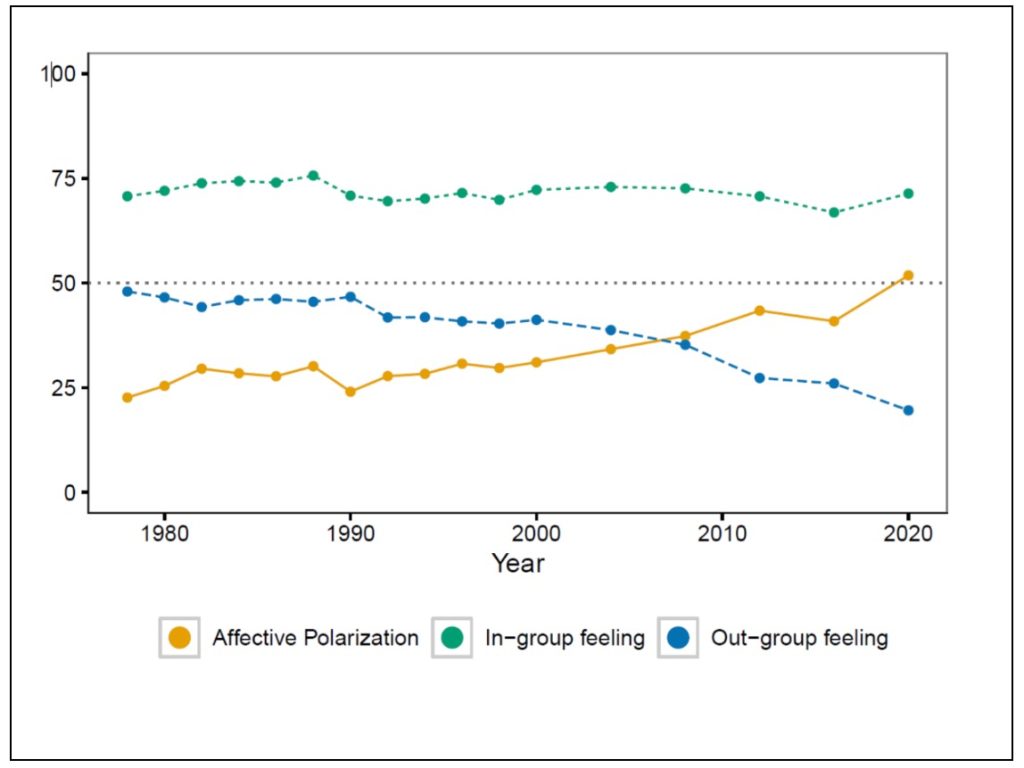

”The unparalleled ANES time series data have made possible the discovery of an entirely new subfield of American politics – the phenomenon of affective polarization or animus across the party divide. Using the ANES feeling thermometers, which date back to the 1970s, scholars documented a significant increase over time in partisans’ hostility toward their opponents. This finding, first published in 2012, has since generated more than 350 published papers (with the term affective polarization in the title) and approximately 1,2000 citations (from Google Scholar). I would add that the ANES database has greatly facilitated my own research over the past decade into partisan affect and the underlying causes of polarization.”

– Shanto Iyengar, Professor of Political Science and Director of the Political Communication Laboratory, Stanford University, and ANES Principal Investigator

“Thanks to the ANES’s commitment to high-quality data, scientists have advanced what we know about social attitudes, policy preferences, and voting behavior, among many other topics. More specifically, ANES data has allowed scientists to unveil opinions on specific issues for different segments of the electorate- for instance, how Americans view immigration, how education relates to political knowledge and participation, or what people like about specific presidential candidates. The large ANES questionnaire gives scientists an extensive list of topics to explore and to understand the American electorate.”

– Francy Luna Diaz, Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan

“[Because of the ANES], we know about the predominant importance of party identification in political evaluations and vote choices. We know how much motivated reasoning exists in politics, and how much of it is driven by party ID. We know about the poor consistency and lack of ideological constraint in the policy views of the American public. We know how little the public knows about their representatives in Congress. We know that the variance in general political knowledge among the American public is high, but the mean is low. We know about the different types of political behaviors that some people perform, and how many performers there are for each of those. Despite what economists think, we know how little tangible self-interest has to do with most political attitudes. We know a great deal about how race, and racism, shapes policy views in the country. We have learned a great deal about the gender gap in American politics.”

– Richard R. Lau, Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University

This post is part of a series celebrating the 75th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). It was developed by Tevah Platt. Read our companion posts on the history of the ANES, its influence on scholarship, and where it stands today.

May 14, 2024 | ANES, Elections, National

A new book by leading scholars of partisanship explores the recent consequences of political hostility, and how it does and doesn’t affect democratic functioning

Is partisan hostility damaging American democracy?

The short answer is yes: Political animosity, which scholars recognize as the defining feature of American politics this century, can degrade democratic functioning. But the question begs for a long answer: To see and face the implications of partisan hostility, we need a nuanced understanding of its effects and its boundaries.

A forthcoming book by some of the foremost scholars of polarization amasses empirical evidence of the consequences of political hostility in recent years, and offers a theory of when it affects political beliefs and behaviors.

Partisan Hostility and American Democracy: Explaining Political Divisions and When They Matter (University of Chicago Press: 2024) will be released June 12 from authors James N. Druckman, Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Levendusky, and John Barry Ryan.

Study after study has shown a striking rise in negative feelings Americans hold toward the opposing party– a concept scholars call affective polarization. Roughly 8 in 10 partisans report these negative feelings, according to Pew Research Center, and the majority use pejorative words– such as “hypocritical,” “closed-minded,” and “immoral” to describe their counterparts. While partisans have maintained stable attitudes toward their own party over time, their “ratings” of the other party have plummeted since 1980 and notably in the last decade. The authors cite New York Times columnist David Brooks’s taut summation– in the age of affective polarization, “we didn’t disagree more– we just hated each other more.”

“We find that partisanship does shape political beliefs and behaviors, but its effects are conditional, not constant,” said co-author Yanna Krupnikov, an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research and a professor in the Department of Communication and Media. “It seems most likely to guide beliefs on issues that don’t have direct personal consequences, and it’s most powerful when parties send strong, clear cues on an issue.”

The authors test that framework using panel survey data from a 21-month period spanning 2019, 2020, and 2021– three tumultuous years that occasioned the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine distribution; the murder of George Floyd and subsequently the largest protest movement in US history; the 2020 election and January 6 insurrection; two impeachments, and a shift in the congressional majority.

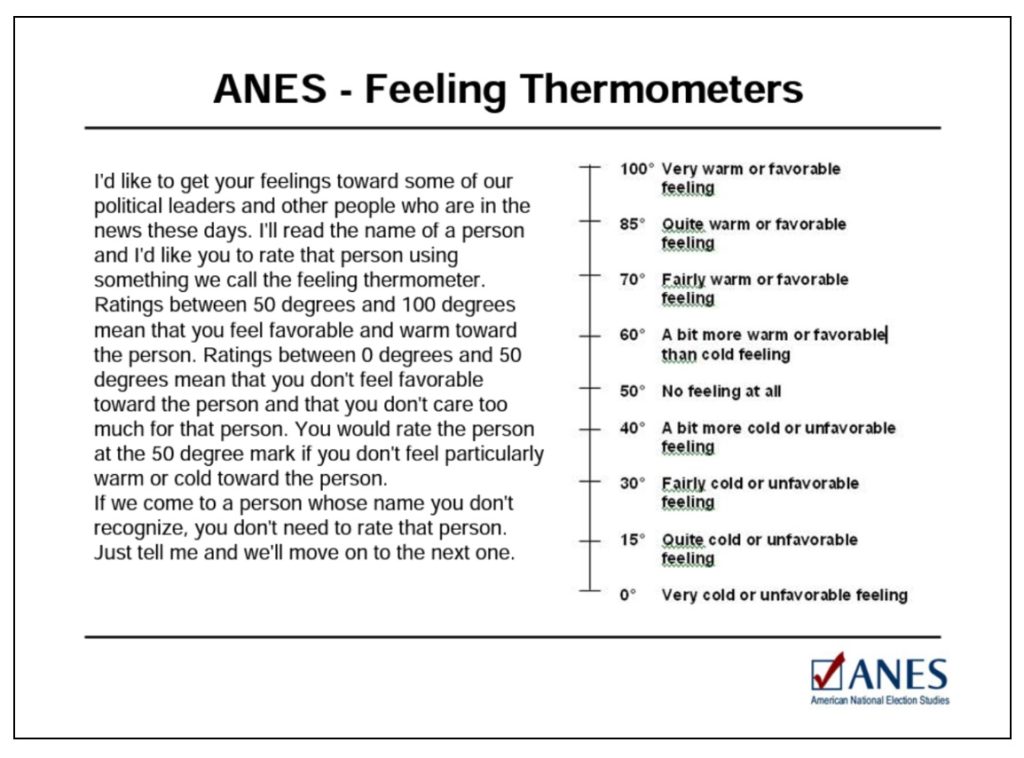

The best data for measuring animosity over time, according to the authors, is the “feeling thermometer” in the American National Election Studies (ANES) survey, where respondents rate their feelings toward a party or issue on a 101-point scale, in which “50 degrees” is the neutral fulcrum between “warmer” or “colder” feelings. The authors use that measure in their own data along with additional measures: trust questions, trait ratings– where respondents evaluate how well positive and negative traits describe each party– and “social distance measures,” where respondents rank their comfort level in situations like having their child marry someone from the other party.

They find the effects of political hostility are most concentrated in individuals with comparatively high animosity, who are a distinctive group in America– with particularly strong political identities and high levels of political engagement. These “high animus” partisans are more likely to take and act on party cues about where they “should” stand, and more likely to reject the possibility of their own party compromising.

We can observe that animosity can fuel polarization on issues that might otherwise be informed by independent deliberation. In 1997, for example, Democrats and Republicans were equally likely to believe in climate change science; today, there’s a pronounced divergence that can only be explained by parties staking a claim on the issue, Krupnikov said.

The authors focus particularly on the case of politicization that drove the gap between Democrats and Republicans’ behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Political hostility is more likely to shape partisan evaluations of party leaders, they report, but the case of Dr. Anthony Fauci demonstrates how party cues can politicize specific targets. The authors also found the effects of COVID’s politicization on behaviors like vaccine or mask resistance diminished when actors confronted the personal stakes of the illness. To further understand these party signal dynamics and when they matter, the authors investigated the effect of animosity on policy positions in cases where issues are politicized by both parties, one party, and neither party.

“The advantage of our theory is its recognition that partisan divides are not inevitable and on many issues most people agree,” said John Barry Ryan, also an affiliate of the Center for Political Studies. “Overall, we see that animosity shapes decision-making by heightening the effects of party cues.”

The authors argue that while partisan hostility has degraded US politics—for example, politicizing previously non-political issues and undermining compromise—it is not in itself an existential threat. Political hostility has little effect on popular beliefs in fundamental norms, and it’s unlikely to directly lead to democratic breakdown or collapse, they say. They also find that overall, partisans do not strongly support undemocratic practices.

Yet there is considerable cause for concern that partisan hostility may erode democracy over time. Political hostility can result in blind loyalty and decision-making based purely on team mindset– with worrying implications– and animosity can spiral because it has self-perpetuating effects.

“We find that animosity has clear, predictable effects on prioritizing party over other considerations, especially for issues that lack clear and immediate consequences to a person,” Ryan said. “It affects policy positions that make democratic functioning difficult– like our willingness to compromise, or our judgments of party leaders, and how we respond to the pandemic.”

“Political elites can politicize issues and can potentially seize on division in hopes of gaining support,” said Krupnikov. “There is often a focus on voter division, but the future of American democracy depends often on how politicians– more than ordinary voters– behave.”

This post was written by Tevah Platt, communications specialist for the Center for Political Studies.

Apr 15, 2024 | ANES, ANES 75th Anniversary, Elections

The American National Election Studies (ANES) has been recognized by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) with its Policy Impact Award– given annually to outstanding projects making a clear impact, improving policy decisions, practice and discourse. The ANES was selected for “making public opinion available to policymakers, informing public discourse, and allowing evaluation of the functioning of democracy.”

With this award, AAPOR recognized the ANES as the longest-running and most widely used and cited time series of public opinion and voting behavior data in the world.

“The entire ANES team is humbled by this award,” said ANES Primary Investigator Nicholas Valentino, Professor of Political Science and Research Professor in the Center for Political Studies (CPS) at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. “In our democracy, public opinion is meant to guide elected representatives’ policy decisions, so informed policy discourse and assessments of democracy require information about public opinion. The ANES collects high-quality data on opinion and behavior that inform policy discourse and allow evaluation of the functioning of democracy.”

AAPOR noted that the ANES has been the leading source of data on public opinion in electoral politics for decades, noting that “nearly all leading issues of national policy in the United States since the 1950s are addressed by the study, including, especially, racial inequality, economic inequality, social capital, campaign finance, voter ID laws, and attitudes and opinions about government institutions.”

The ANES is a national infrastructure project for research about the public’s relationship with government, Valentino said. For 75 years, it has provided public access to high-quality data built around two main outcome variables: turnout and candidate choices in elections for federal office. To explain these outcomes, ANES questionnaires cover policy preferences, identity, prejudice, values, behavior, knowledge, and demographics, with an emphasis on high quality sampling and measurement. “The resulting datasets inform policy discourse and take the vital signs of democracy.”

As illustrations of the durable and far-reaching impact of the ANES, AAPOR noted the breadth, number, and diversity of organizations that have cited or relied on the data in their policy advocacy or discourse– including the high branches of government, the lower federal courts, foreign and internationally-focused organizations, policy think tanks and advocacy organizations. In an increasingly polarized media environment, AAPOR recognized that ANES is frequently cited in the news media, and by all sides. The model established by the ANES has been the inspiration for national election studies in over 30 countries around the world. The impact on research about democratic society is illustrated by over 8,000 papers, books, and other publications that have used ANES data over the past 75 years. Finally, AAPOR cited the ANES as the most cited dataset in peer-reviewed articles about public opinion and political behavior in the leading political science journals — used by thousands of scholars, journalists, students, and citizens to understand American democracy.

“ANES policy impact is broad, but two important and timely foci are campaign finance and voter ID laws, where ANES is regularly cited in legal briefs, policy advocacy, and non-partisan reports,” said Valentino.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the ANES: Since 1948, the definitive study of American political attitudes and behavior has run national surveys of citizens before and after every presidential election, providing a rigorous, non-partisan basis for understanding contemporary issues as well as change over time.

Valentino noted that the ANES has a legacy of AAPOR recognition as scholars using ANES data have been lauded over decades. The first winner of the AAPOR Award for career achievement, Angus Cambpell, won largely for the work he did to create the ANES, Valentino said. Numerous subsequent AAPOR Award winners – including Philip Converse (1986), Howard Schuman (1994), Norman Nie (2006), Michael Traugott (2010), Stanley Presser (2011), Jon Krosnick (2014), and Lawrence Bobo (2020) – each rely heavily on ANES data in their work (and Converse and Krosnick were ANES principal investigators).

“It is a great honor for ANES to continue in this intellectual tradition, and we would all like to thank the selection committee at AAPOR,” said Valentino. “[It is also important] to mention that the ANES staff is large and makes a huge contribution to the project’s success.”

The ANES is a collaboration of the University of Michigan and Stanford University, with Duke University and the University of Texas, and is funded by the National Science Foundation.

AAPOR has offered the Policy Impact Award annually since 2004. Last year’s winners were the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and the National Study of Caregiving (NSOC); previous honorees include the U.S. Census Bureau, the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, the RAND Corporation, and the Urban Institute.

In addition to Valentino, Shanto Iyengar of Stanford University is a principal investigator of the project. The Associate PIs are D. Sunshine Hillygus of Duke University and Daron Shaw of the University of Texas at Austin. David Howell and Matthew DeBell are the Directors of Operations at Michigan and Stanford, respectively.

The Center for Political Studies has recently published a series on the 75th anniversary of the ANES: Including a Q&A about the project with Nicholas Valentino, a visual history of the project, and reflections from scholars who have been impacted by the ANES.

Two CPS students also received awards from AAPOR this year: Francy Luna Diaz and Zoe Walker, both Institute for Social Research Next Generation Scholars, won AAPOR Student-Faculty Diversity Pipeline Awards, which aim to recruit faculty-student “pairs” interested in becoming AAPOR colleagues to study public opinion and survey research methodology.

This post was developed by Tevah Platt.

Apr 4, 2024 | ANES, ANES 75th Anniversary

Every year, hundreds of publications, dissertations, and scientific conference papers are written using data from the American National Election Studies (ANES). The ANES has had a profound impact on the study of American political attitudes and behavior and the work of generations of scholars who have used this national resource. In recognition of the 75th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES), the Center for Political Studies reached out to a few of those scholars to reflect on how the ANES impacted their research.

“To my mind, the ANES has been the single most important resource in my career in political psychology.”

–David O. Sears, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, UCLA

“When I was a graduate student in the 1970s I thought the study of American democracy was the study of public opinion and the study of public opinion was working with ANES data. My favorite party game was “Michigan Marginals” – competitive guessing the response distributions to questions in the NES codebooks. I’m older now and enthusiastic about different things, but I still believe the ANES is one of the world’s finest social science institutions, with its greatness only growing as the Time Series extends. I was incredibly lucky to have ANES data for my dissertation and later work, as have been hundreds of others.

“I would like also to say a few words about Warren Miller and Steve Rosenstone, the leaders of ANES in its formative period. I knew them at close range as a member of the ANES Board of Overseers and am still in awe. A couple of anecdotes: ANES data were released to the public at a set time and no one, not even Warren Miller, could peek ahead of time. I still remember him hovering nervously over a new data release, waiting until the clock reached noon to flop open the book to see how the numbers for his beloved variable, Party Identification, had been affected by the recent election. And Steve Rosenstone, a scholar of turnout, leading a study that concluded ANES’s investment in validated vote report was creating as many errors as it was correcting and should be terminated. The integrity, foresight, and political skill of these two leaders was an inspiration to behold. Near the end of my career now, I’ve been associated with many academic institutions, and I have no hesitation in saying that the ANES they led was hands down the finest.

“And can I end a tribute to ANES without mentioning Phil Converse, the greatest scholar of anything I know about? I never really knew him, but I wouldn’t be me without him.”

– John Zaller, Professor Emeritus of Political Science, UCLA

“I will forever be indebted to the ANES. Data from the cumulative file served as the basis of one of my dissertation essays, as well as my first solo-authored publication. It’s not an exaggeration, then, to say that the ANES played a big role in landing me my first (dream) job at Brown. That’s among the many reasons I was honored to serve on the Board for the 2016 election cycle. I can’t imagine a time when I won’t rely on ANES data for research and teaching – there’s no better source for trends in U.S. political behavior and elections.”

– Jennifer Lawless, the Leone Reaves and George W. Spicer Professor of Politics and Professor of Public Policy, University of Virginia

“I became a behavioral political scientist that day in the early 1960s when I first touched an “analysis deck” of the 1956 Michigan Election Study (not yet called ANES). Sixty or so years later the excitement of that moment is still with me. A fourth of a continent away from Ann Arbor and as an undergraduate I could test ideas that, at least so far as I knew, had never occurred to anybody before. My testbed then was the novel instrument called the counter-sorter and the method was literal cross-tabulation. I immediately began to think of myself as a voting behavior analyst, even before graduate school. And it stuck. Even though my scholarly trajectory has switched away from the micro behavior questions that initially motivated me, I have never been weaned from the ANES. I have exploited every biennial or quadrennial study and am sure that will eventually include the yet to come 2024 study — even in retirement. My debt to the ANES is everything I am.”

– James Stimson, Raymond Dawson Distinguished Bicentennial Professor of Political Science Emeritus, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

“Directly observing political behavior is important and often the most valid measurement—but we also need to understand what goes on in people’s heads. For that, surveys are indispensable. But not every survey is the same. The ANES provides a long-running, credible benchmark for many survey-based measurements in political science. Its historical value can’t be argued with, yet its significance in contemporary political science is just as great: Thanks to unrivaled resources and the pooled experience of many experts, the ANES continues to form a foundation on which all of us can build.”

– Markus Prior, Professor of Politics and Public Affairs at Princeton University

“The ANES time series has been invaluable to my research—at that of many other social scientists—on generations. This research focuses on whether Americans differ depending on when they were born and what they experienced when coming of age, and on whether generational replacement is fueling social and political trends, such as partisan realignment and dealignment; declining civic engagement, political participation, and trust; and growing secularism, liberalism, egalitarianism, and polarization. Studying generational dynamics requires what the ANES time series supplies: repeated population-based surveys stretching across decades. With each additional study, we gain more leverage for understanding the interplay of politics, history, and demographics.”

– Laura Stoker, Professor Emerita of the Graduate School in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley

“My career as a political scientist is unimaginable without the ANES. I’ve been exploiting the wealth of data produced by the time-series studies and a variety of auxiliary studies for five decades. I’ve used them for dozens of journal articles, from my earliest in the 1970s through this year. NES* data were a prime inspiration for, and remain a core component of, The Politics of Congressional Elections, now in its 11th edition, and they have been important to my two more recent books on public opinion and the presidency. I doubt there are many more avid consumers of ANES data.

“Equally if not more important to my professional life was my involvement in helping to produce the data. I was toiling in obscurity as an assistant professor at Trinity College, working on a project that had me appending campaign spending data to NES data (using self-typed punch cards) and had the idea that the survey would be greatly enhanced (and my workload greatly reduced) if the studies included contextual data—on such things as campaign expenditures in the respondent’s district, of course—along with the survey data. My mentor, Dave Mayhew, suggested I make a proposal for the 1977 NES conference that would be considering ways to investigate congressional elections. I did, was invited to the conference, and ended up on the NES Committee on Congressional Election Research for the next decade, eventually chairing it. Later, I also served on the NES Board of Overseers and in that capacity chaired the committee that designed the 1990 Senate Election Study.

“From the beginning, working with NES was a fantastic experience. Not only did I get to see some of my ideas (usually greatly improved) work their way in to study designs and questionnaires that became the data I later analyzed, I also got to work with and befriend the finest election scholars from three generations: my heroes from the generation of Warren Miller and The American Voter, the hot shots of my own cohort, and a younger group of budding academic stars telling us how to get election studies right. Many became lifelong friends. If I tried to name them all I would use up all my space (for reference, most are thanked in the prefaces to PCE). I got a lot of my education as a social scientist well after graduate school, and my involvement with the ANES community was at the heart of it.”

*The ANES was known as the National Election Studies (NES) from 1977 to 2005.

– Gary Jacobson, Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Political Science, UC San Diego

This post is part of a series celebrating the 75th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). It was developed by Tevah Platt.

For a future post, we’re interested in your input on what the ANES has revealed about key moments, decades, or patterns in American history. Tell us what you think with this quick Google form.

Mar 5, 2024 | ANES, ANES 75th Anniversary

The American National Election Studies (ANES) is the definitive study of American political attitudes and behavior, recognized for setting “the gold standard” in survey research in political science. The project has surveyed American citizens before and after every presidential election since 1948. With a time series of core questions asked continuously across many elections, these surveys provide a window onto the sweep and the pivot points of historic change in American public opinion. In recent studies, new questions comprise about 30 percent of each survey, allowing users to understand contemporary issues that might be driving American political dynamics. Funded by the National Science Foundation since 1977, the ANES is both national scientific infrastructure and a touchstone of political science research.

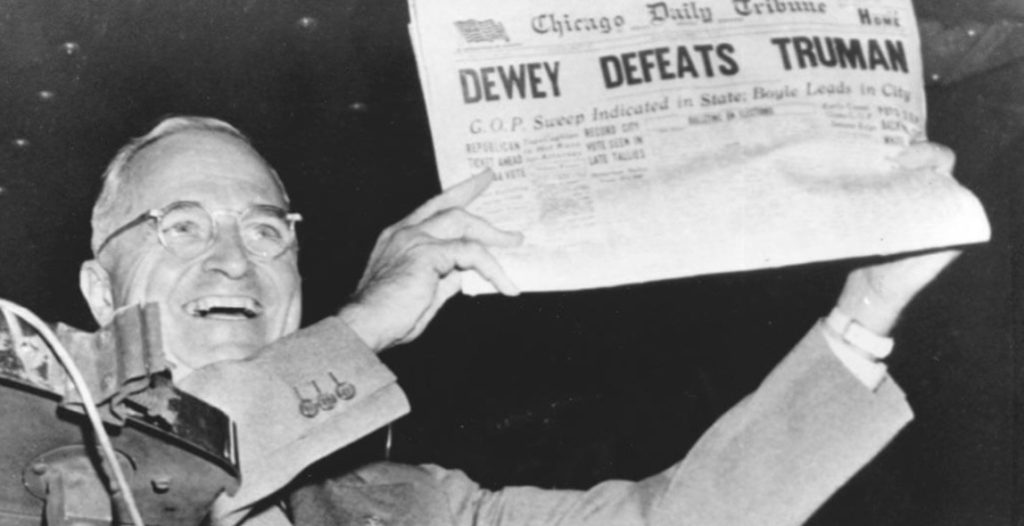

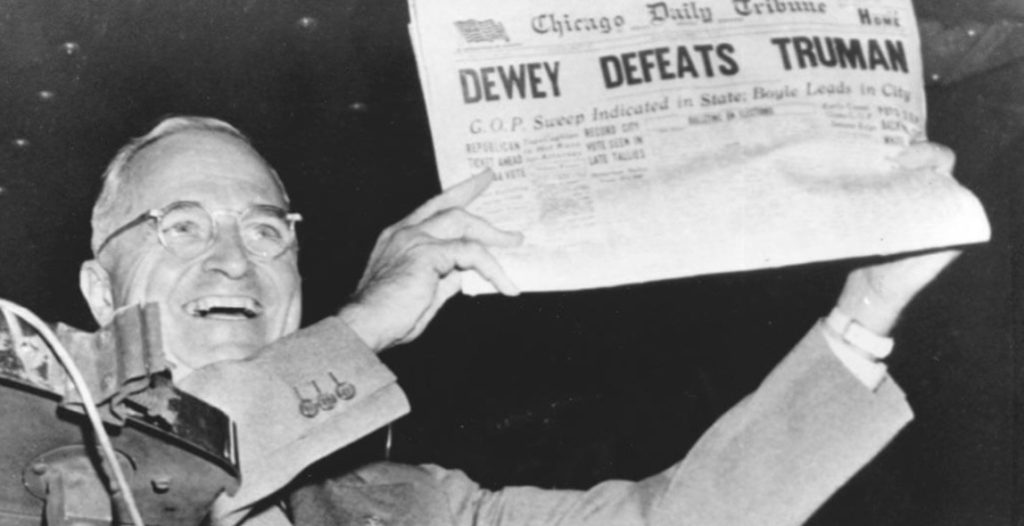

The Beginning (1948-1952)

In 1948, under the direction of Angus Campbell and Robert Kahn, the Survey Research Center carried out what is viewed as a pilot study of the national electorate. Fortuitously, the study pioneered survey sampling methods that outperformed commercial polls in predicting the presidential race that year. The “Dewey Defeats Truman” debacle– when the Chicago Daily Tribune famously ran the incorrect banner headline on its front page following Truman’s upset victory– provoked an inquiry into election survey methodology. on matters such as sampling and personal interviewing that helped set a new standard for scientifically valid surveys, market research, and public opinion polling. The first Michigan monograph, The People Elect a President, by Robert Kahn and Angus Campbell, was based on pre- and post-election interviews of 662 respondents: and those original survey responses are still available from ICPSR.

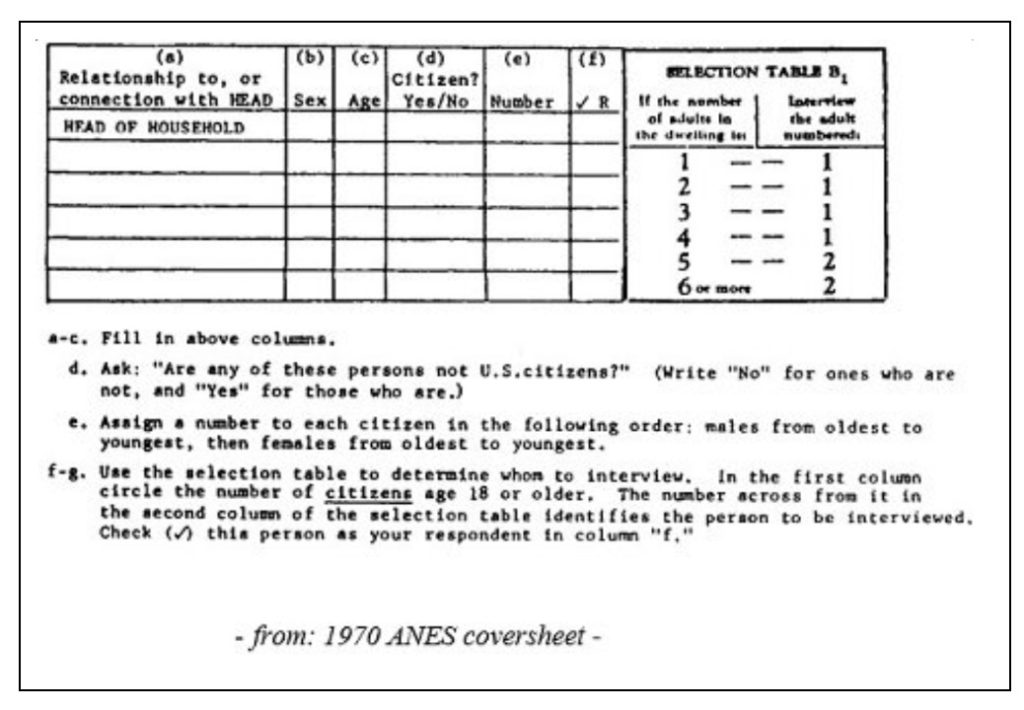

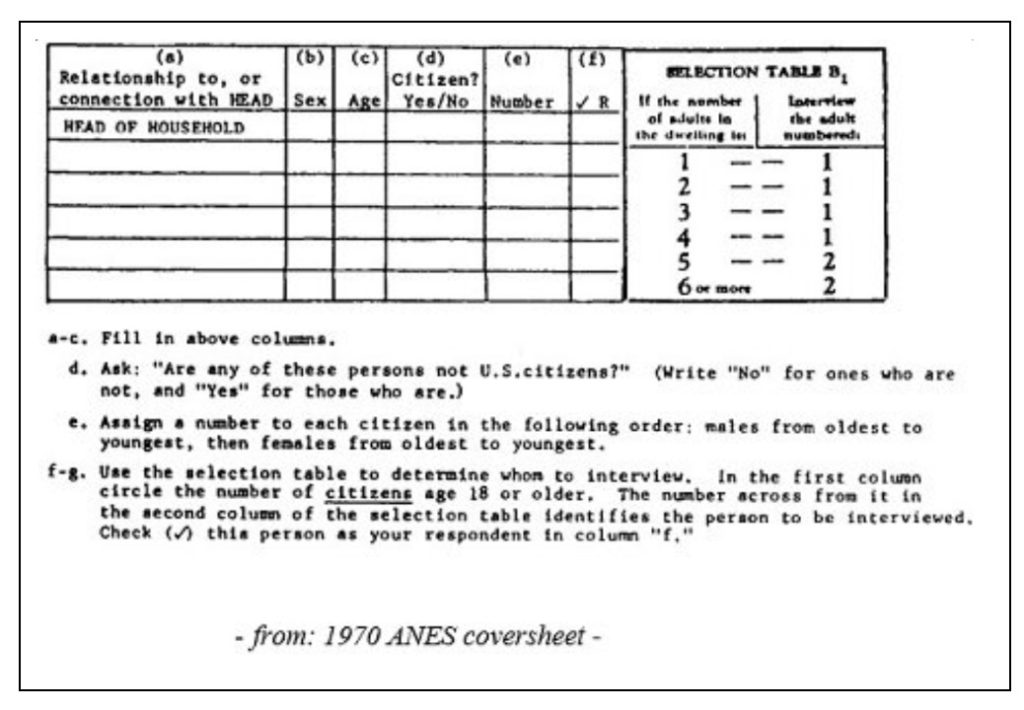

Since the early days of the study, a central goal has been to develop and implement the newest and best methods for conducting survey research. For example, the 1948 survey introduced the Kish grid, a method for randomly choosing household respondents, pictured below. As John Aldrich wrote in the ANES’s 2017 board report, the statistician Leslie Kish was also responsible for the “multi-stage cluster sampling approach that still defines the current backbone of the ANES study design.”

The Michigan Election Studies (1952-1976)

When Warren Miller was hired as the assistant study director of the Survey Research Center, his dissertation proposed a project that was adopted almost in its entirety in the 1952 election study, and used for planning further studies that became known as “the Michigan Election Studies” located at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research (ISR). The Michigan studies would cover all 13 presidential and midterm elections between 1952 and 1976.

The Fifties

It’s worth pausing to imagine the intellectual environment of ISR in its early years. As former ANES PI Virginia Sapiro wrote in remarks on the ANES’s 50th anniversary, ISR’s formation in 1948 was based on a series of connections that brought founders of the blossoming new field of social psychology together with an interdisciplinary group of social scientists. This included psychologists such as Dorwin Cartright, Jack French, and Robert Zajonc at the Research Center for Group Dynamics, whose work on “ego strength” influenced concepts of “personal competence” and “political efficacy” that first appeared in the 1952 Michigan election study. In the years after World War II, there was wide interest in the study of authoritarianism and democratic norms. The election study benefited from this new force of social scientists at ISR, trained in new methodologies, many out of the Department of Agriculture and the wartime Office of Strategic Services. ISR had technical and mechanical resources, such as punch card machines, to code and analyze data, and teemed with opportunities for intellectual collaboration. For the election studies, Sapiro wrote, this period was marked by “the initiation of creative expansion of the research program that ultimately transformed it into one of the most influential social science projects of the post-World War II era.”

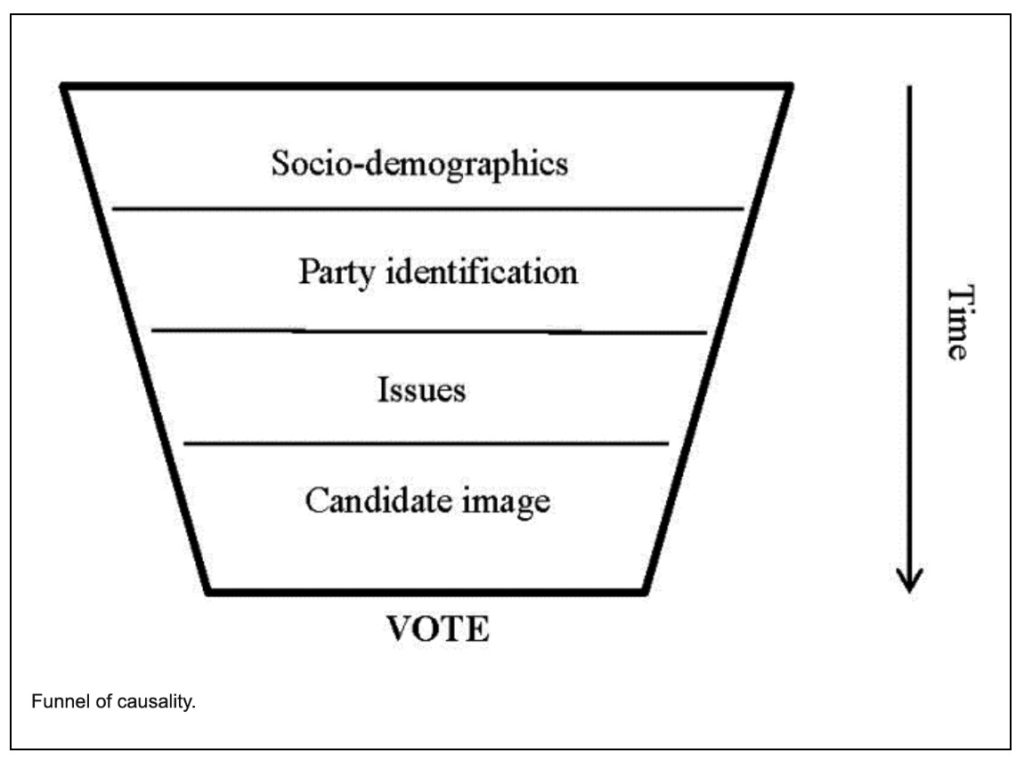

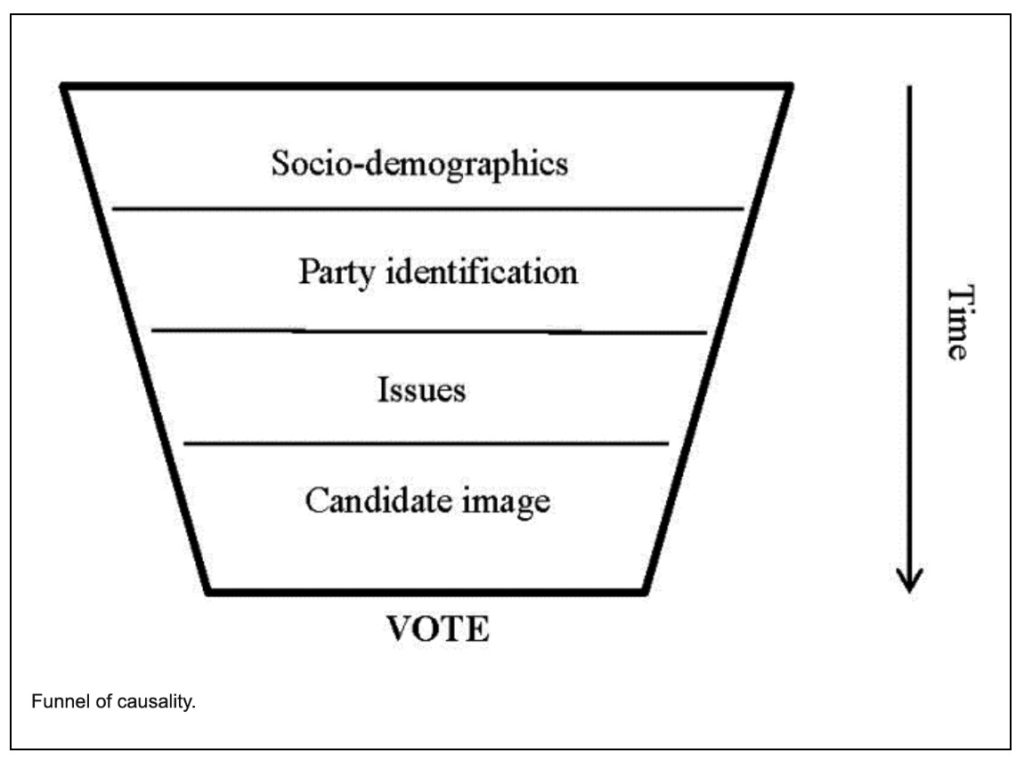

Over its first decade, the Michigan collaborators developed what’s known as the “Michigan model,” a theory of how voters make choices based on a “funnel of causality” involving sociodemographic factors, party identification, and, shorter-term, issue orientations and candidate evaluation.

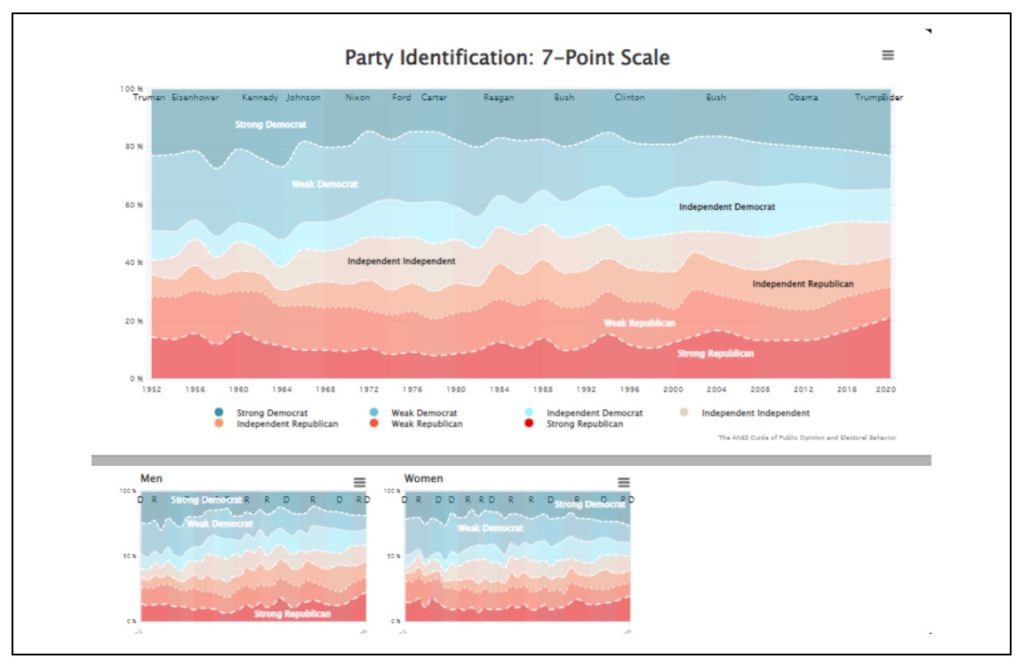

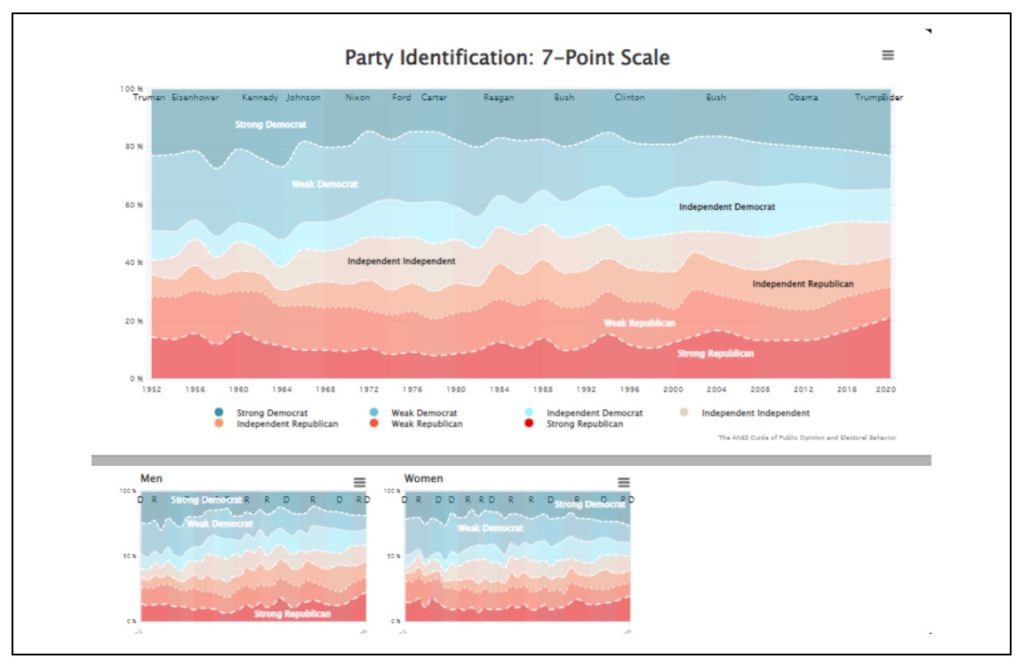

The 1952 ANES survey introduced the new measure of “party identification” to assess whether voters possessed deep psychological attachments to one of the parties. The idea that people acquire long and stable affinities for specific parties that transcended feelings about candidates and issues in any one election, then novel, has become central to our understanding of how people vote. Most scholars of political science now see this as the core predisposition shaping political beliefs and behavior.

Pictured in this photograph from the Bentley Historical Library, from left to right are Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Angus Campbell, circa 1956, as they review the sampling design of their new survey. Philip E. Converse and Donald E. Stokes, then promising graduate students, also joined the team that year.

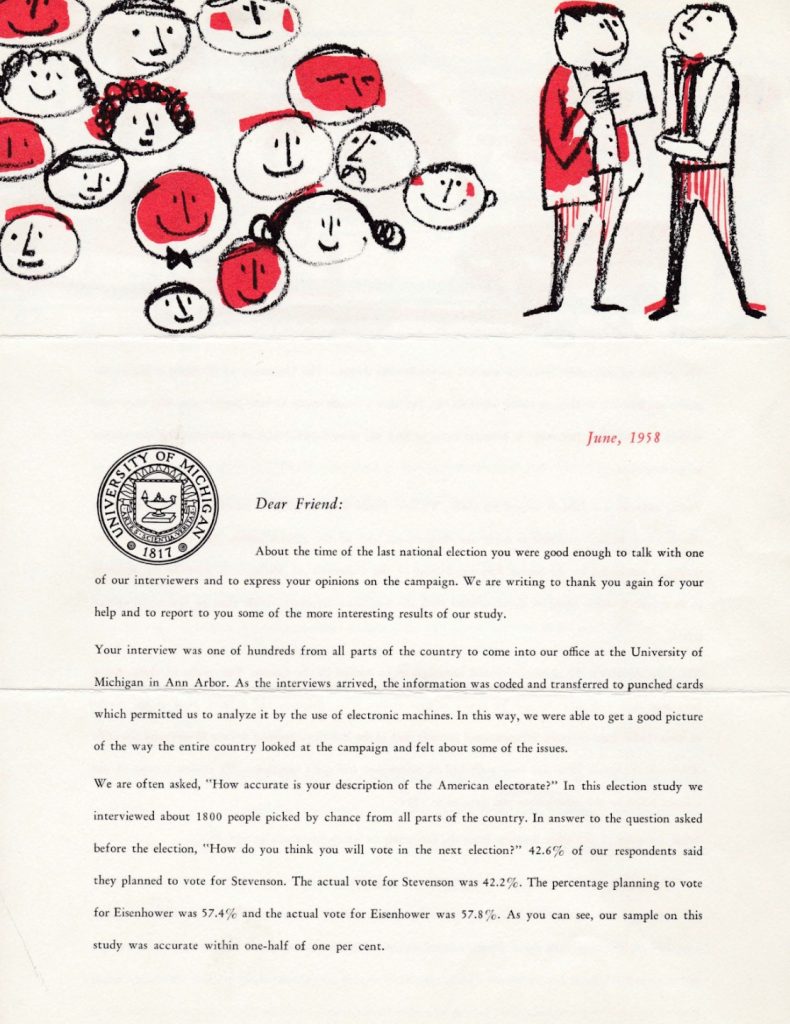

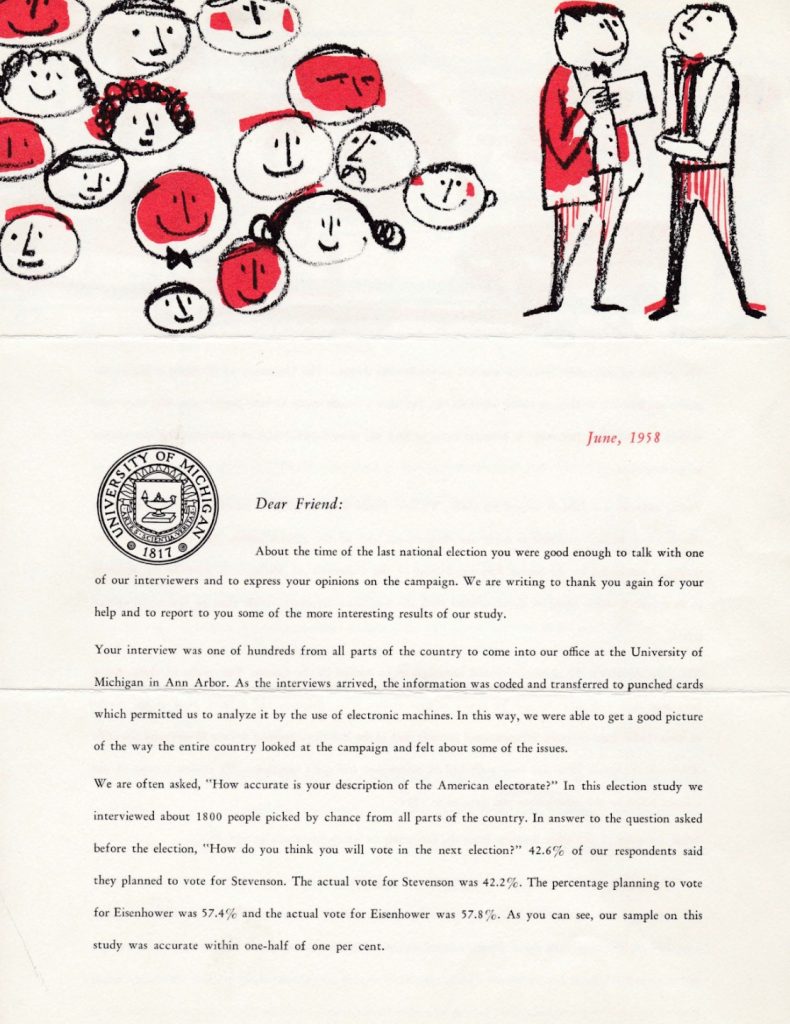

In the pictured letter, we see an example of a respondent letter mailed to survey participants after each election. This example, from 1958, describes the punch card system used to analyze interview content and the accuracy of the results. (The 1958 election study found the percentage planning to vote for Eisenhower was 57.4%. The actual vote was 57.8%.) This letter was sent by Angus Cambell, PI of the study from 1948 to 1960, to respondents who participated in the 1956 Time Series survey. (Find more about the history of the ANES principal investigators here).

The Sixties

Capping the work of the prior decade, The American Voter, written by Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes, was a seminal study based on ANES data, published in 1960. It launched a new field of research into the beliefs and attitudes that shape voter decision making.

The studies of the 1960s were responsive to changing national political circumstances. In 1960, for example, new questions emphasized the role of religion and helped capture the extent to which anti-Catholic sentiment reduced Kennedy’s margin of victory. In 1964, the study added a special sample to better understand the politics of Black Americans. In 1968, the survey addressed militarism, racism, and as Warren Miller phrased it, “[issues] having to do with the rather unique appeal of George Wallace to the older voter.”

The 1960s also occasioned what may be the most dramatic shift in American electoral history this century. As described by Rutgers Professor Richard Lau, the Michigan studies captured “the major realignment of the American party system that occurred mostly during the 1960s because of the civil rights movement, desegregation, and busing.”

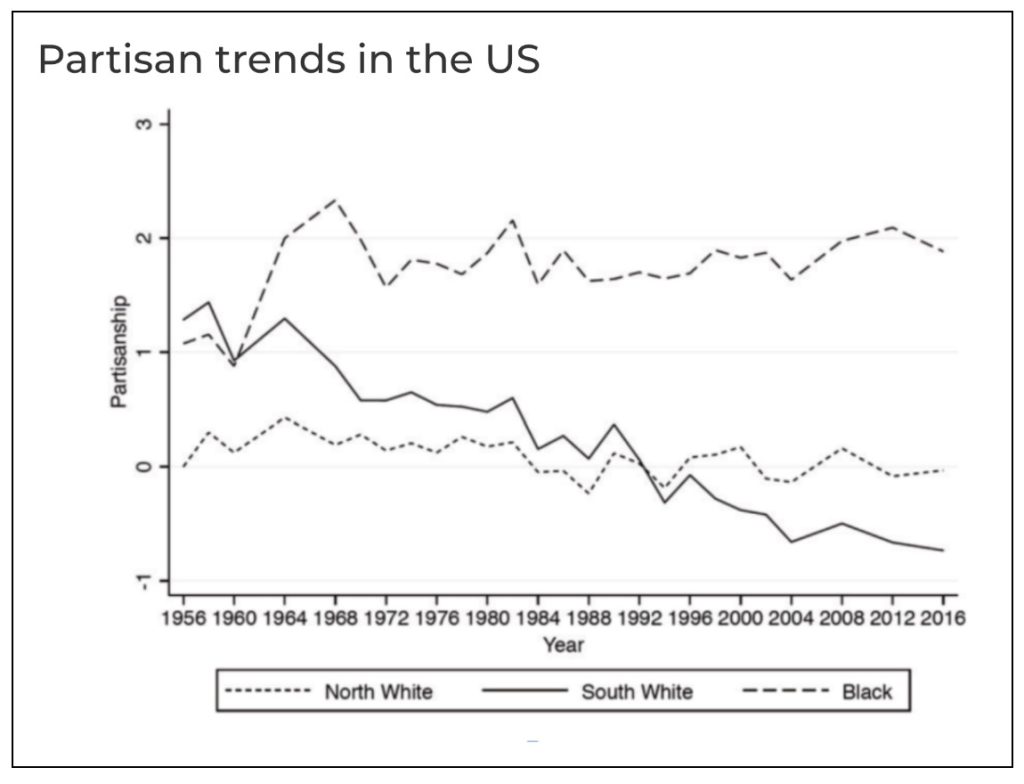

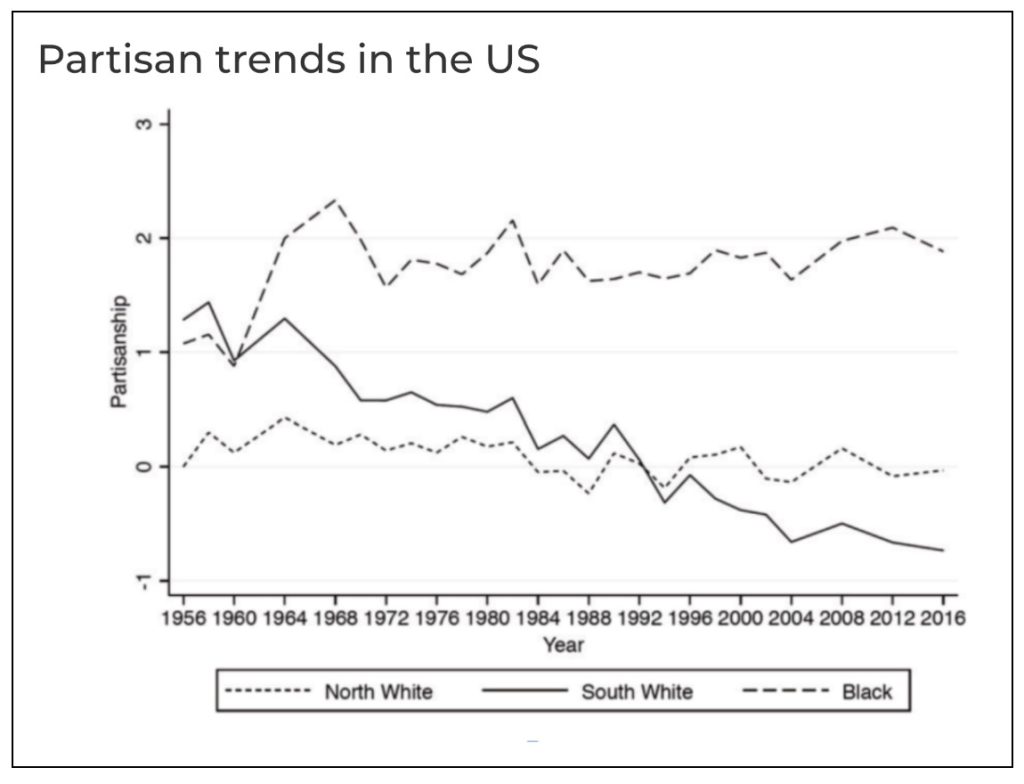

The graph below from Dynamic Partisanship: How and Why Voter Loyalties Change by Ken Kollman and John E. Jackson plots partisanship among three groups of the U.S. electorate– northern whites, southern whites, and Black voters– from 1956 to 2016, with Democratic partisanship increasing along the y axis. Northern white partisanship is particularly stable; Southern white partisanship shows a graduate shift from “moderately Democratic” to “weakly Republican” over six decades. But the 1964 election stands out as a critical turning point in African American partisanship, making a dramatic leap and remaining consistently high on the Democratic scale after the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

The introduction of the “feeling thermometer” in 1964 was a key innovation in measurement that has helped to capture “affective polarization”– the shifting feelings people hold toward political parties– over time. The feeling thermometer remains a widely used tool for measuring how voters feel about a specific person or group.

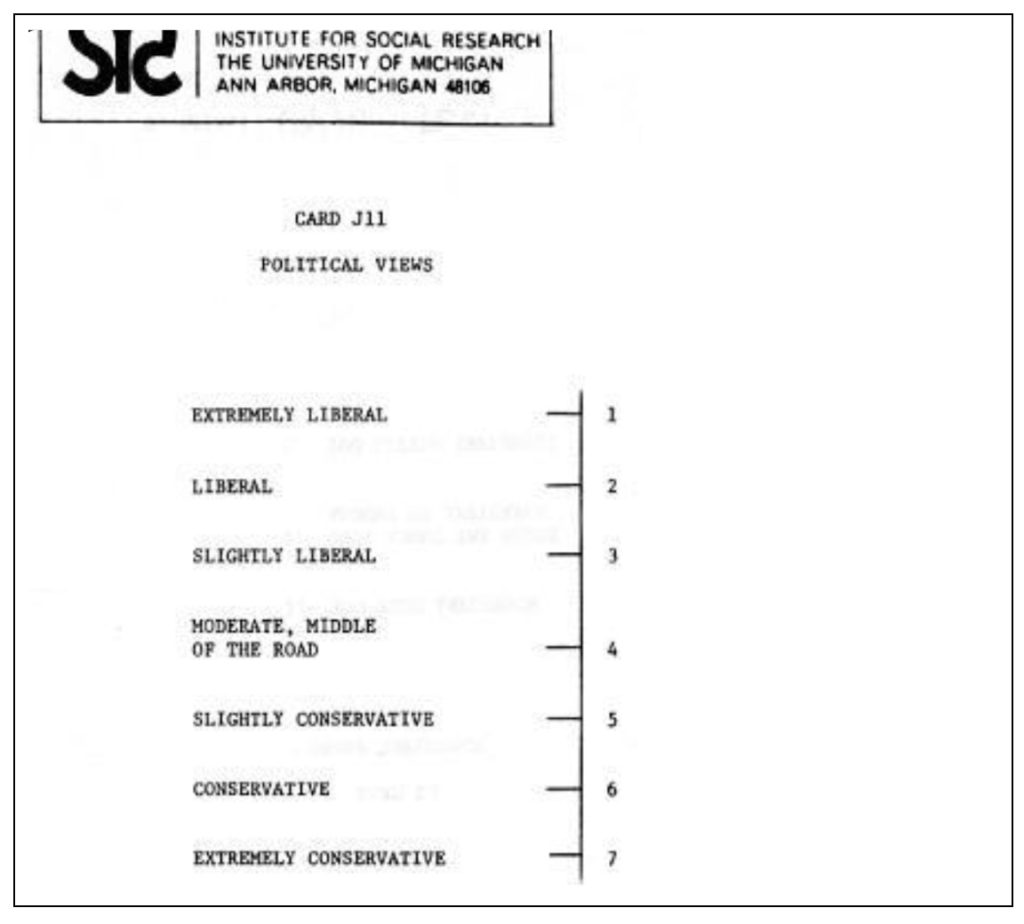

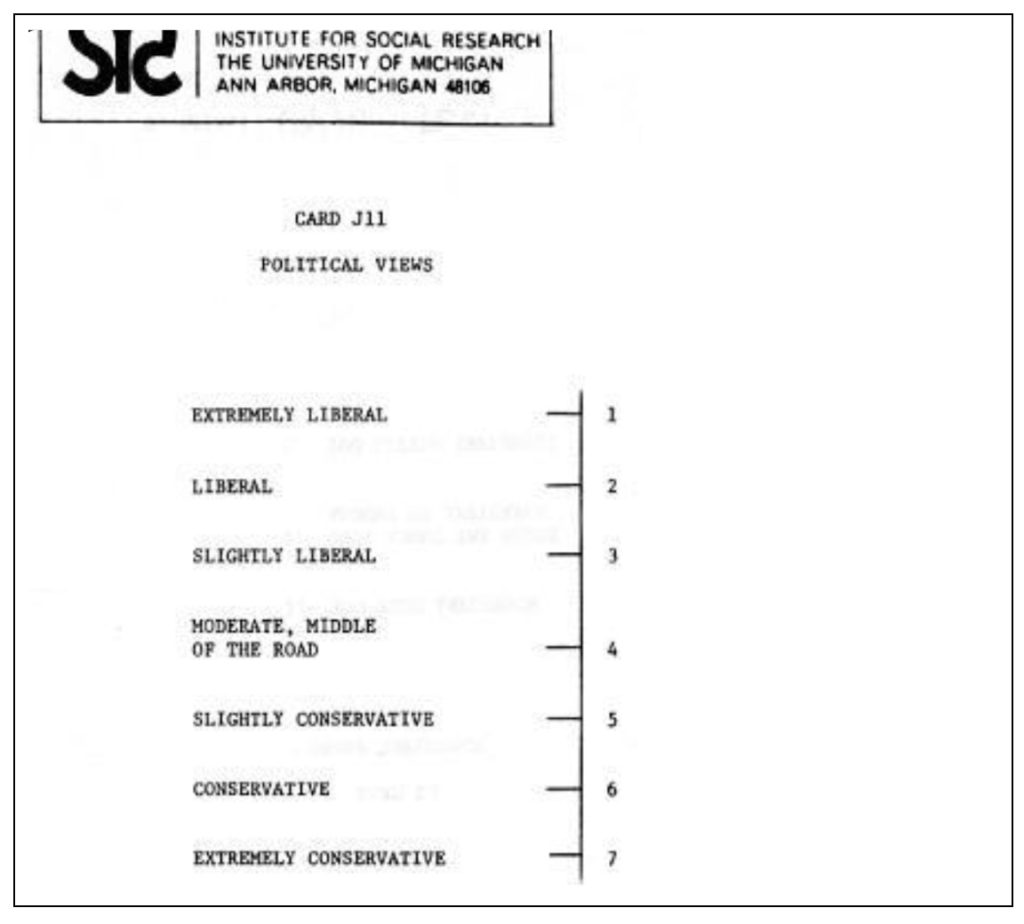

The other major innovation in measurement dating back to the 1960s was the “seven-point Likert scale,” introduced in 1968 and now omnipresent in survey measurement. The invention of this scale came out of the work of Richard Brody and Sidney Verba in a study of attitudes toward the Vietnam War.

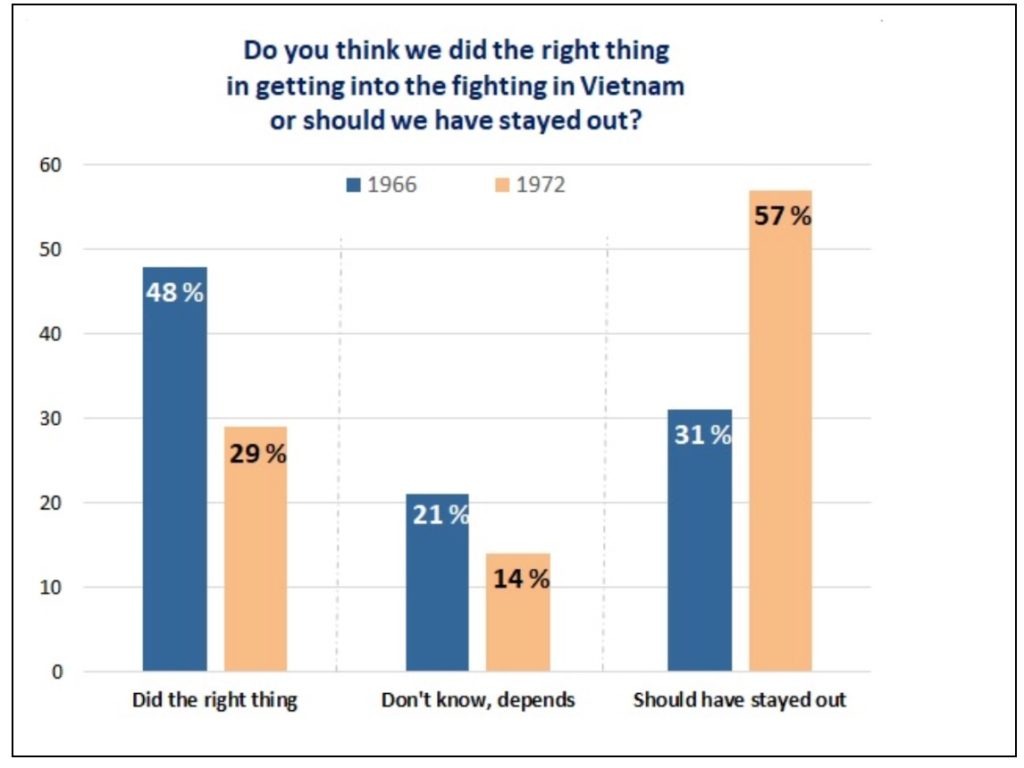

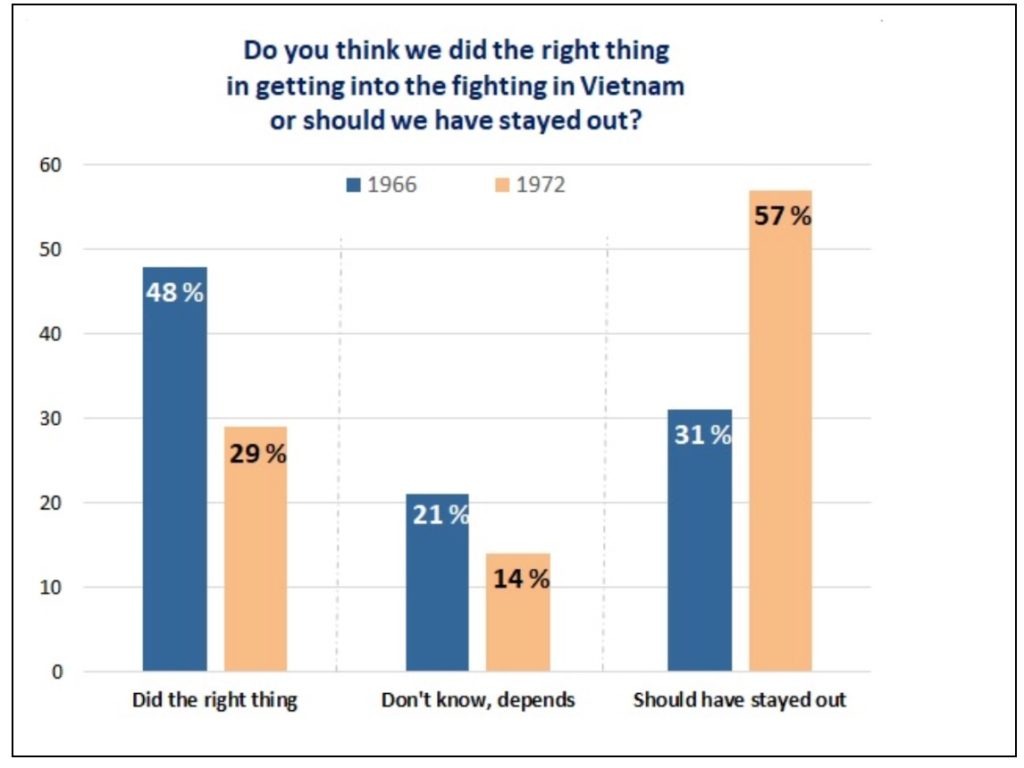

The project began asking Americans in 1966 if the US “did the right thing in getting into the fighting in Vietnam.” The 1972 survey results documented the shifting tide of public opinion. While 48% of respondents in 1966 thought the US had “done the right thing in getting into the fighting,” that number by 1972 had dwindled to 29%.

The Seventies

In 1970 the principal investigator for the election studies became the newly founded Center for Political Studies (CPS) at ISR. By this time, ANES historians note that the studies had become an extraordinary resource for large segments of the social science research community: “Placed in the public domain by the archival and data dissemination facilities of the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), the Michigan studies provided the quantitative data base for a very large number of important investigations in several disciplines, supporting social research carried out by scores of investigators, and utilized by hundreds of teachers and thousands of students.”

In the words of Warren Miller, the 1970s was also the occasion for “systematic attempts to broaden the input of the user community in the specification of Michigan election study content.”

A new area of focus for the study, dating to 1974, was the impact of mass media on electoral behavior– an area that has become a discipline in itself.

It’s fair to say the election studies were also impacting mass media by providing not only information but key concepts for analytical methods used to understand public opinion. Warren Miller helped various networks to develop their election coverage, and as a consultant for ABC News, Miller coined the term “projection” that remains in use today to describe estimated election outcomes.

Photo source: Chance Magazine, courtesy of Jack Moshman. Mike Traugott, Jerrold Rusk, and Warren Miller with members of the ABC News team. Circa 1968.

Questions about trust in government have been asked since the very early days of the election studies. The vast majority in early years believed that “not many” or “hardly any” in government were crooked. After Watergate evidence was released to the public in 1974, the percentage fell by 9 points. (Trust in government would again diminish over time after 2000).

The National Election Studies (1977-2005)

In 1977, the National Science Foundation (NSF) designated the National Election Studies (NES) as “a national research resource.” Its governing board that year referred to the NES as a “national resource for the social sciences analogous to high energy accelerators, telescopes, or oceanographic laboratories.”

Its mission was extending the time series collection of core data, and developing instrumentation and study designs to facilitate the testing of new theories of voting and public opinion. The principal investigator of the National Election Studies would now be supervised by an NSF-appointed board, whose charge included identifying the broad interests of the national and international research communities served by the survey.

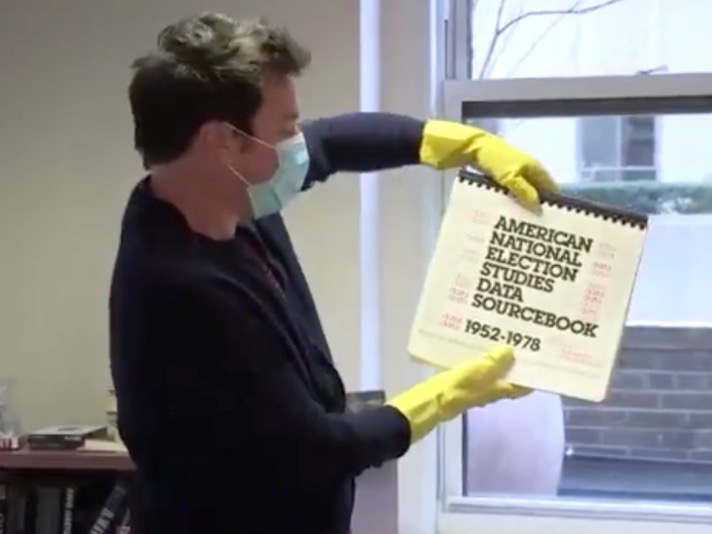

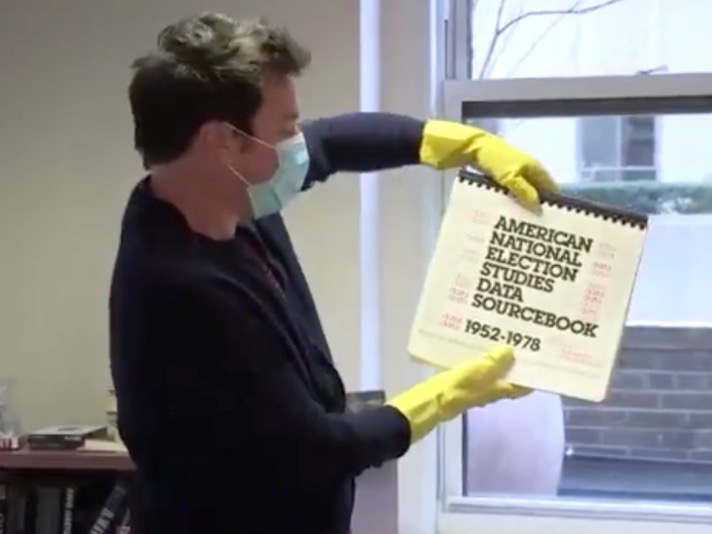

In 1979, Harvard published the ANES Data Sourcebook 1952-1978. Providing tabular percentages across years for measures repeated comparably over the multiple Time Series studies, the sourcebook was a predecessor to the online ANES Guide to Public Opinion and Electoral Behavior. The ANES’s Time Series Cumulative Data File would later become the most downloaded dataset in the ANES archive. Pictured below in a 2021 Tonight Show segment, Jimmy Fallon picks up a copy of the Sourcebook found while cleaning out the MSNBC office of political analyst Steve Kornacki.

The Millennial Shift

Technological changes at the turn of the millennium influenced the collection, development and distribution of the NES data. In 1980, the first phone interviews were conducted by NES administrators who recorded responses on paper questionnaires. Computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) and personal interviewing (CAPI) techniques were used and compared against face-to-face interviewing techniques in the 1982 Methods Comparison Study. The subsequent growth of the internet radically altered communication with NES’s user community and the distribution of its data. In the late 1990s, the NES distributed data through its FTP site and released a CD-ROM that contained the data and supporting documents of all the studies it had mounted to date. The advent of the internet also made new sampling techniques available, supplementing the NES resource that remains unique today in its sampling and measurement quality.

This period was also pivotal for the NES moving from national barometer to global participant. The NES had long been a model for the development of election studies around the world. Then in the early 1990s, the NES was a founding member of the most significant comparative study of democratic politics, the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES). Every five years, election studies participating in CSES collaborate on developing a new module of questions that is then included in post-election surveys globally, enabling analyses that compare citizen attitudes and behaviors across countries and different electoral contexts. The NES incorporated the CSES for the first time in its 1996 data collection; the year 2024 will be the seventh time that the CSES has been included in the NES.

Pictured below: attendees of the 2014 CSES Conference and Plenary Session in Berlin, organized by the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB) and supported by the Center for Political Studies.

The American National Election Studies, 2005-present

In 2005, the ANES began a collaborative effort between the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan and the Institute for Research in the Social Sciences at Stanford University.

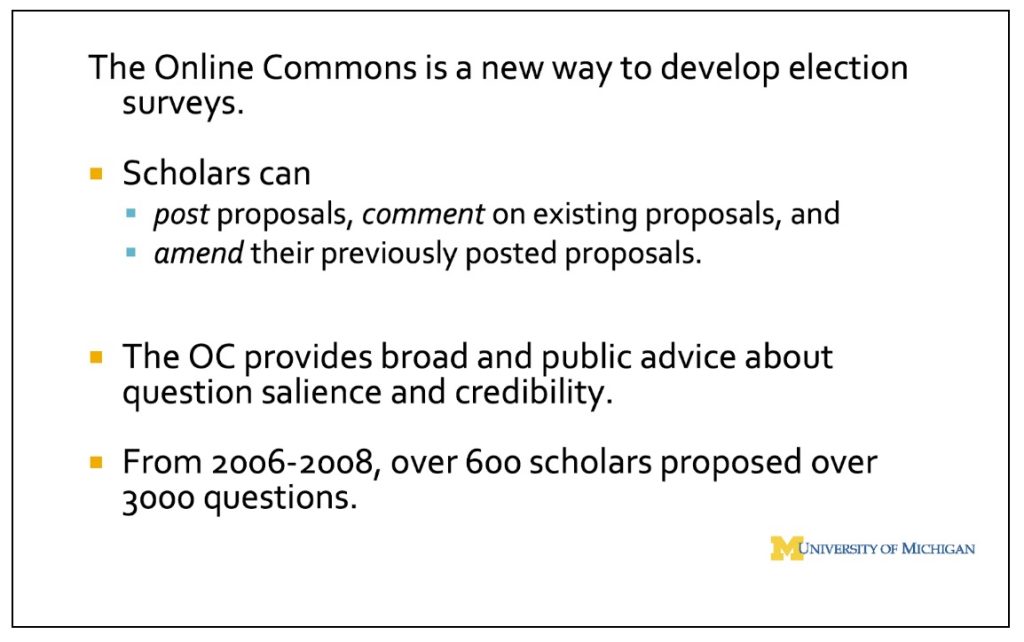

In 2006, PI’s Arthur Lupia and Jon Krosnick opened the “Online Commons,” a forum for the research community and the public to submit new ideas for future studies. From 2006-2008, over 600 scholars proposed over 3,000 questions.

In 2010, the NSF included the ANES in its “Sensational 60,” a list of advancements that have had a large impact on every American’s life.

Recent History

Photo source: Nicole Baster, via Unsplash

Perhaps the most important trends captured in the past decade of the ANES have been decreasing trust in government and increasing affective polarization, or animosity across party lines.

“The unparalleled ANES time series data have made possible the discovery of an entirely new subfield of American politics – the phenomenon of affective polarization,” writes ANES PI Shanto Iyengar. “[The documentation of] a significant increase over time in partisans’ hostility toward their opponents, first published in 2012, has since generated more than 350 published papers (with the term affective polarization in the title) and approximately 12,000 citations (from Google Scholar).”

The 2016 study introduced new questions on trade, immigration, economic inequality, LGBT issues, outsourcing, policing, and social mobility. That same year, the ANES tested the collection of high-quality Internet samples, comparing these to in-person interviews.

This year also inaugurated the 3-wave panel (2016-2024), interviewing more than 2,000 people from a high-quality, representative sample over three presidential elections for the first time in ANES’s history.

Conducted between 2018 and 2022, a massive scanning project funded by the NSF added 5 million pages of content to the ANES’s digital archive.

(Photo courtesy of ANES staff)

The 2020 Time Series study was designed by the Principal Investigators Ted Brader and Shanto Iyengar with help from Associate PI’s Nicholas Valentino, Sunshine Hillygus, Daron Shaw, an experienced staff, and with input from the ANES Advisory Board and user community. The ANES added questions about Black Lives Matter and police conduct, and initiated its Social Media Study, the first nationally representative data set linking social media use to political behaviors.

In 2022, the beta version of the ANES Guide to Public Opinion and Electoral Behavior was released with improved formatting, visualizations, and interactivity.

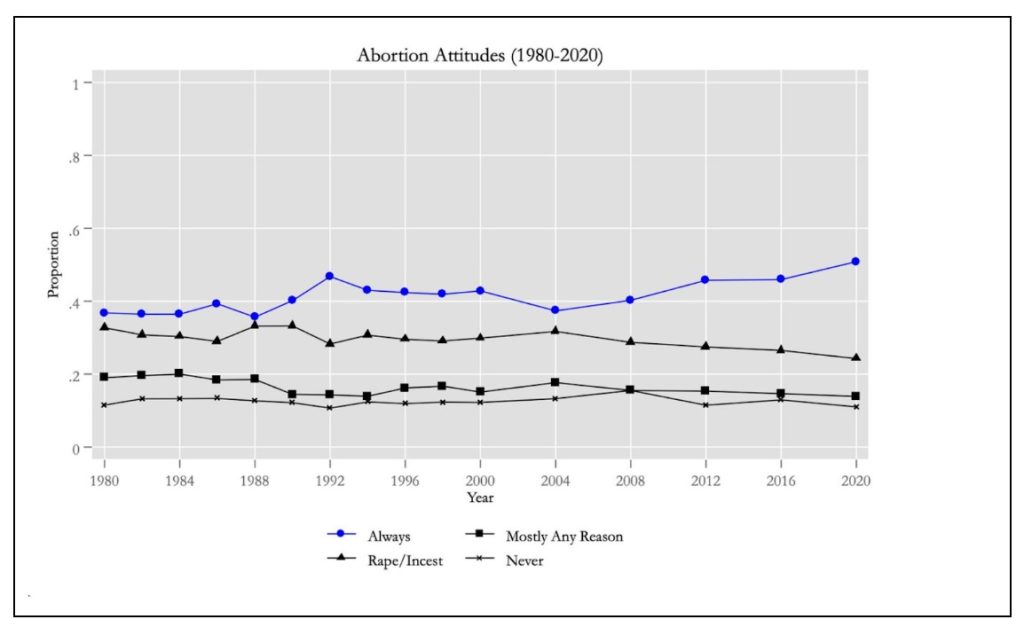

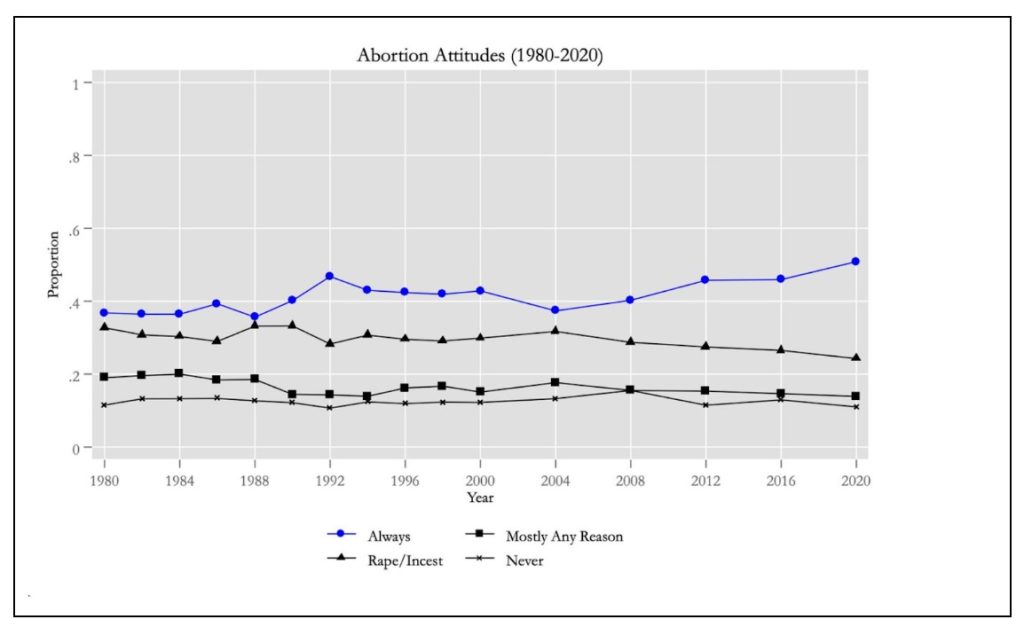

Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs, overturning Roe vs Wade, the 2022 ANES pilot study began beta testing new questions on abortion. Pictured here: A graph of election studies’ data on abortion attitudes, posted to Twitter/X by political scientist Ian Shapiro, shows an increase in support for the option that by law, a woman should “always” be able to obtain an abortion as a matter of personal choice.

The Future of the ANES (2024-)

In 2022, the NSF awarded $14m to the ANES to study 2024 elections to a PI team including Sunshine Hillygus, Shanto Iyengar, Daron Shaw and Nicholas Valentino. In 2024, the ANES will complete its 3-wave panel interviewing the same respondents over three presidential elections for the first time in the ANES’s history. Valentino notes that the 2024 elections will occur “at a moment of great uncertainty and change in American politics. Long-standing political norms involving executive power, electoral legitimacy, and the rule of law…are under challenge.” Trust in government is at an all-time low; polarization in America is at its most venomous. Without the ANES, we would not be able to know where these trends began, and so long as the ANES remains funded, we will have a national resource that shows us where we’ll have gone from here.

The ANES is currently a collaboration of Duke University, the University of Michigan, Stanford University, and the University of Texas at Austin, with funding from the National Science Foundation.

Its current principal investigators are Shanto Iyengar, Professor of Political Science and Director of the Political Communication Laboratory at Stanford University, and Nicholas Valentino, Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Research Professor affiliated with the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. The Associate PIs are D. Sunshine Hillygus, Professor of Political Science and Public Policy and director of the Initiative on Survey Methodology at Duke University, and Daron Shaw, Distinguished Teaching Professor and the Frank C. Erwin, Jr. Chair of State Politics at the University of Texas at Austin.

Sources and Further Reading

- John Aldrich, “The American National Elections Study as ‘Gold Standard’ for Survey Research in the Twenty-First Century,” Board Report, 2017.

- Nancy Burns, “The Michigan, then National, then American National Election Studies,” 2006.

- The ANES (electionstudies.org) history, previous principal investigators, and timeline.

- Warren E. Miller, “An Organizational History of the Intellectual Origins of the American National Election Studies,” European Journal of Political Research 25: 247-265, 1994.

- Virginia Sapiro, “Fifty Years of the National Election Studies: A Case Study in the History of ‘Big Social Science,’’ delivered at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Atlanta, 1999.

- Herbert F. Weisberg, “Reflections: The Michigan Four and their Study of American Voters: A Biography of a Collaboration,” American Political Science Association, 2016.

This post was developed by Tevah Platt.

Feb 13, 2024 | ANES, ANES 75th Anniversary, Elections

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the American National Election Studies– the definitive study of American political attitudes and behavior. The ANES has run national surveys of citizens before and after every presidential election since 1948, providing a rigorous, non-partisan basis for understanding contemporary issues as well as change over time. According to the National Science Foundation, the ANES provides “gold-standard data on voting, public opinion, and political participation in American national elections.” The Center for Political Studies interviewed ANES Principal Investigator Nicholas Valentino to gather his reflections on the history of the ANES, what we’ve learned from it, and where we’d be without it. This interview has been edited and condensed.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the American National Election Studies– the definitive study of American political attitudes and behavior. The ANES has run national surveys of citizens before and after every presidential election since 1948, providing a rigorous, non-partisan basis for understanding contemporary issues as well as change over time. According to the National Science Foundation, the ANES provides “gold-standard data on voting, public opinion, and political participation in American national elections.” The Center for Political Studies interviewed ANES Principal Investigator Nicholas Valentino to gather his reflections on the history of the ANES, what we’ve learned from it, and where we’d be without it. This interview has been edited and condensed.

It’s the 75th anniversary of the ANES. What do you want people to know about it?

VALENTINO: It’s really important to remind ourselves about how important the ANES has been in terms of a gold standard survey, both methodologically and substantively, that other polling outfits use as a benchmark. We don’t often talk about those things, because we assume it is well known how important the ANES is for the entire discipline. But it is important that the ANES collects the highest quality samples; we care a lot about measurement, and we don’t change measures unless we know that the alternative is a better measure of the concept that we’re trying to tap. Every year, hundreds of dissertations and publications are written using ANES data. That means ANES data appear in thousands of scientific works per decade, and tens of thousands over the life of the project.

This is the most centrally important study of American public opinion and political behavior in existence.

What’s unique about the ANES survey?

VALENTINO: With the rise of other less expensive samples and sampling methods, especially volunteer internet samples, entire generations of students are now able to collect data on their own rather than rely on infrastructure projects like the ANES. This is no doubt a great innovation, because each scholar can learn a lot about new topics and perform survey experiments for which the ANES is not well suited. But these new samples and sampling techniques can’t match ANES’s data quality both in terms of measurement practices and the sampling quality. They can’t provide valid and reliable estimates of opinions that the population holds because they do not collect representative samples of the country. They can’t replace address-based samples and the face-to-face interviewing methodology that the ANES has employed (with the COVID-year exception in 2020) for 75 years. And, perhaps equally importantly, with its time series questions, the ANES allows one to measure population level change in opinions over time. The ANES is very unique for both of these reasons, and so we think it has made good on the hopes of its founders 75 years ago.

Let me say a bit more on how the ANES represents truly invaluable infrastructure for the entire discipline. The Department of Astronomy at Michigan recently invested in the instrumentation program for the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), which is a consortium of universities and partners building the largest optical telescope in the world. Few universities can afford to build their own telescopes; instead, they buy into a measurement strategy that is fundamentally collaborative. The National Science Foundation supports these big projects, because they know that scholars from universities around the country can use the telescope regardless of the research budgets on their home campus. Well, that’s what the ANES is doing for the study of public opinion and political behavior. We include questions on the survey that have been asked before because we want continuity of measurement, and that are interesting to the broadest array of users in the community. The user community has several mechanisms for influencing the content of the ANES, including specific proposals and by serving on the large and diverse Advisory Board.

Where would we be today were it not for the ANES?

Valentino: One example is that we are currently very concerned about affective polarization or the polarization of society along lines of party. It was once the case that Democrats and Republicans didn’t dislike each other very much at all. In fact, if you ask Democrats and Republicans how warmly they felt toward their own party and toward the out-party, they once gave both roughly the same score. If you track this in the ANES over time, we see that after the 1980s there was a dramatic, continuous increase in how much Americans disliked members of the other party. That discovery has triggered a wide ranging set of inquiries about whether it was driven by elite preferences, differences in the party platforms, or by something that was changing in the electorate. We’re still trying to answer this question about why. But we wouldn’t really have known how big the problem was, or when it started, if not for the ANES. The ANES tells us when it started, and how fast it grew. And those pieces of information are very critical for understanding why it happened.

What kinds of questions have been asked continuously over the history of the ANES?

Valentino: It must have been very hard in 1950 to know which questions to ask, especially if one wanted to begin a time series that would last 75 years. You can imagine how different the world was when Warren Miller and his colleagues started thinking about what questions they should ask. One example of a question we have asked continuously over time is, “How much do you trust the government to do what’s right?” If you look up the trend on government trust on the accessible web page– the ANES Guide to Public Opinion and Electoral Behavior– you will see a dramatic decline in the percentage of people who say they trust the government to do what’s right. This trend is one of the things people point to when they worry about democratic backsliding and the deterioration of democratic norms. Back in the late 1950s, in the Eisenhower era, almost 80% of Americans said they could trust the government “most of the time or just about always.” Now that number has decreased to about 20%. Another question has been asked for quite some time on this topic: “Are governmental officials crooked?” At one time the vast majority of Americans responded “not many,”or “hardly any.” Since 2008, there has been a massive increase in the share of the electorate from either party who say “quite a few” elected officials are crooked. So that’s a massive shift and a decrease in trust that we’re aware of because of the ANES asking the same questions consistently over time. Americans’ trust in government hit its nadir in 2020– making the future of the ANES particularly valuable for understanding how democracies react to declines in public confidence.

What have we learned from the ANES about how voters select their candidate?

Valentino: One of the early discoveries of the founders of the ANES was that psychological attachments to parties themselves are group identities.

Party identification is the core predisposition shaping political beliefs and behaviors. In other words, it may be that votes are driven most strongly by those partisan identities rather than a citizen’s individual preferences on a bundle of policies. That discovery can have a very scary set of implications.

Most definitions of democracy insist that citizens have the ability to freely choose candidates who represent their issue preferences and hold elected officials accountable when they fail to produce results consistent with their campaign promises. So what if pre-existing attachments to parties drive vote choices even when candidates are not delivering on issues or economic performance? In that system, leaders could pursue policy interests divorced from the majority’s will. It reduces the impact that issues, trends, and performance have on democratic elections. If so, elections increasingly resemble sports events, in which it is forbidden to criticize the home team.

The ANES has documented a long-term shift in party identification, and especially a decline in Democratic dominance from the 1950s to the present. Over time, there is a lot of variation in partisan attachments that is not predicted by social group memberships. You might look at individual-level psychological forces to explain, for example, how white, blue-collar Democrats were pushed toward the Republican party after the Civil Rights movement. That is a dynamic you couldn’t understand by looking solely at social group memberships or by considering material interests. The early scholars of the ANES were among the first to discover that, contrary to popular belief, people don’t vote with their personal pocketbooks. People are motivated less by their own financial security than by how they think the country is doing as a whole. Americans, at least until very recently, support the incumbent if the country is doing well, even if that candidate is from the other party. The ANES was central in discovering this pattern. It will also be central for understanding how these long-term linkages between economic performance and support for incumbents may be breaking down.

What have we learned from the ANES about why some voters participate in politics and others don’t?

Valentino: It is often remarked that political science has few “laws” – theories that are so powerful and elegant that they have reached the status of a settled scientific explanation for important phenomena. One exception is the Civic Volunteerism model of participation proposed by Verba, Schlozman and Brady (1995). This theory claims that people turn out because they want to, because they’ve been asked to, or because they can. Those forces– engagement, recruitment, and resources– are all measurable, and the ANES measures them over time. The model has done a fantastic job explaining who will participate in politics in a variety of ways.

But short-term forces also matter. For example, people with a lot of resources participate in some elections but not others, and some people who have very few of these advantages participate, even though the model might predict that they wouldn’t. The short-term forces are also measurable, and many political psychologists are working on those. We have, for example, identified short-term emotional dynamics that can drive people to the polls– sometimes, but not others– even holding resources constant. You need to ask people about the emotional intensity they are experiencing in a given election, the intensity of competition between the candidates, about campaign negativity, and the tone of political discourse. These factors have also been measured by the ANES, and so our theories of participation are getting stronger and more comprehensive.

How and why are new questions added to the ANES?

Some parts of the ANES every election are about mapping long-term trends, but about 30% of the content on the ANES is concerned with the contemporary moment. People think that the ANES is only about asking the same questions, 75 years straight, but that is a profound misconception. The project solicits input from the user community every cycle, and relies on its diverse Advisory Board to identify contemporary issues it must explore. The ANES actively cultivates new questions about very new issues that might be driving the dynamic in a given election year, but may or may not be permanent parts of our landscape. And we try to balance those new inquiries against the space needed in order to measure long-term trends. Only then can political science as a discipline understand how we got to this point, and predict where we might be going.

Takeaways:

- The ANES is a centrally important study of American public opinion and political behavior.

- The ANES provides gold-standard data on voting, public opinion, and political participation in American national elections, priding itself on sampling quality and measurement quality.

- Looking at long-term trends, we currently stand at a low-point for Americans’ trust in government and an all-time high for affective polarization. These trends are understandable because the ANES’s time series questions track change over time.

- The ANES has demonstrated that political identity plays a strong role in determining how voters choose candidates.

- People participate in politics when they are interested, asked to participate, and have the resources to participate. But short-term factors like the emotional intensity of an election also matter. The ANES survey measures all of these factors.

- In recent cycles, about 30% of the survey has been dedicated to new questions investigating contemporary issues based on input from its community of users.

- Tens of thousands of dissertations and publications have been based on data from the ANES over the project’s history.

Nicholas Valentino is Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Research Professor affiliated with the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1998. His research focuses on political campaigns, racial attitudes, emotions, and social group cues in news and political advertising. His current work examines the intersection between racial attitudes and emotion in predicting political participation and vote choice, as well as the sources of public support and opposition to immigration in the U.S. and cross-nationally.

The ANES is currently a collaboration of Duke University, the University of Michigan, Stanford University, and the University of Texas at Austin, with funding from the National Science Foundation.

This post was developed by Tevah Platt.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the