May 3, 2024 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International, National, Race

The national movement for divestment reflects the prevalence of prosocial politics.

by Eugenia Quintanilla

Activism on university campuses against U.S. investments in Israel has skyrocketed in the past several weeks. As of May 2, over 90 college campuses had Gaza solidarity encampments demanding university divestment from companies supporting Israel. Despite the historical precedence of campus activism on foreign policy matters (see opposition to the Vietnam war, South African apartheid, and the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq), there is public confusion about the popularity, depth, nature, and size of the university divestment movement. Onlookers blame the prevalence of pro-Palestinian activism on everything from limited syllabi at top universities, peer pressure effects, and even college students not having enough sex.

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting provocative slogans. Beyond tents and sleeping areas, many encampments feature Liberation Libraries, communal art-making, and worship spaces for Jewish and Muslim participants. At the University of Michigan, students from the TAHRIR coalition have organized daily programming including teach-ins, external speaker events, documentary screenings, and broader community education initiatives.

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting provocative slogans. Beyond tents and sleeping areas, many encampments feature Liberation Libraries, communal art-making, and worship spaces for Jewish and Muslim participants. At the University of Michigan, students from the TAHRIR coalition have organized daily programming including teach-ins, external speaker events, documentary screenings, and broader community education initiatives.

Student protestors and organizations have put forth specific demands and on some campuses, including Rutgers, the University of Minnesota, Brown University and Northwestern University, have reached agreements after negotiating tangible wins for the protesters related to divestment and protection of civil liberties. All of this work is happening on the heels of final exams, and commencement season, a time when college students should be the busiest. Yet activists at Emory, Columbia, UT Austin, New York University and other universities have faced brutal actions from police, violent anti-protestor attacks, more than 2,000 arrests, suspensions, and demands by political elites to call in the National Guard.

Starting and maintaining encampments is costly activism, requiring time, resources, and a willingness to endure bodily harm and legal repercussions. All of these costs should in principle reduce the likelihood of activism. But activists remain steadfast to their demands and actions, despite what we may expect. How can we better understand this wave of committed activism for Palestine?

Many Americans, I argue, are driven to political action by what can be called their prosocial politics, or their disposition to help groups in need. In what follows, I show the prevalence of prosocial politics as a driver of participation and how partisanship conditions the types of groups that Americans consider “in need.”

The Politics of Helping Others

Studying what mobilizes citizens to participate in politics is a foundational question to social scientists. Traditionally, this research analyzes citizens at the level of the individual. According to the “economic model,” individuals are essentially self-interested actors, and how they understand the costs and benefits of action determines whether they will participate. In the civic voluntarism model, an individual’s level of education, money, and time also make participation more likely.

However, more recent research shows the importance of group participation norms in determining likelihood of participation. Individuals who hold a norm of helping those in need are more likely to participate in higher-cost political participation. Psychology research on prosociality echoes the importance of helping as a cultural value, and an innate human behavior. If helping others is so important to human societies, how can we incorporate the desire to help into our models of political participation?

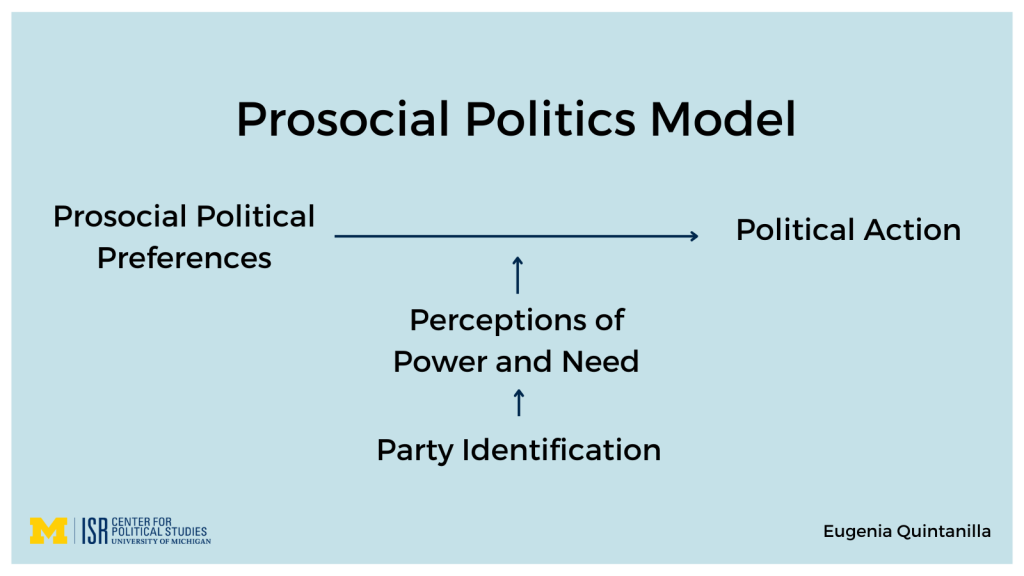

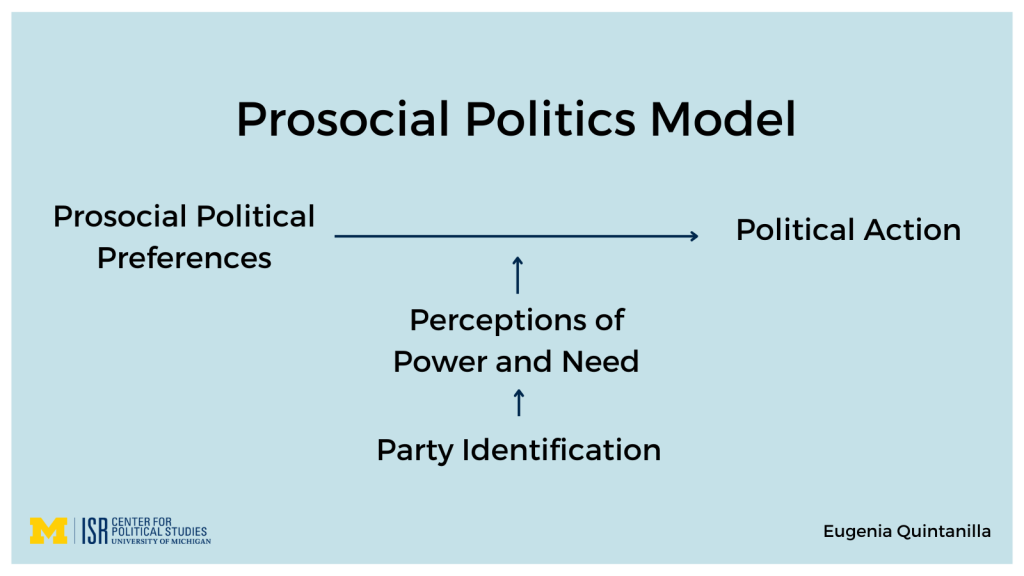

To answer this question, I offer a new theory called the “prosocial politics model.” In this model, citizens’ participation in politics is driven by how much they see helping others as a political value. The influence of this value is particularly strengthened by clarity around which groups are in need, and which groups are in power. As such, in the prosocial politics model, when citizens encounter a political situation they make automatic appraisals about three things:

- Whether helping others through politics matters to them

- Whether the group in question needs help, and

- Whether to take political action to help a group.

To establish evidence of the model in action, I created a measurement of prosocial political preferences in the form of six survey questions. I asked about civic prosocial norms and how helping is tied to politics in questions like, “In elections, how important do you think it is to vote in order to help others?” and “How much do you think politicians should focus on helping groups who are usually ignored?”

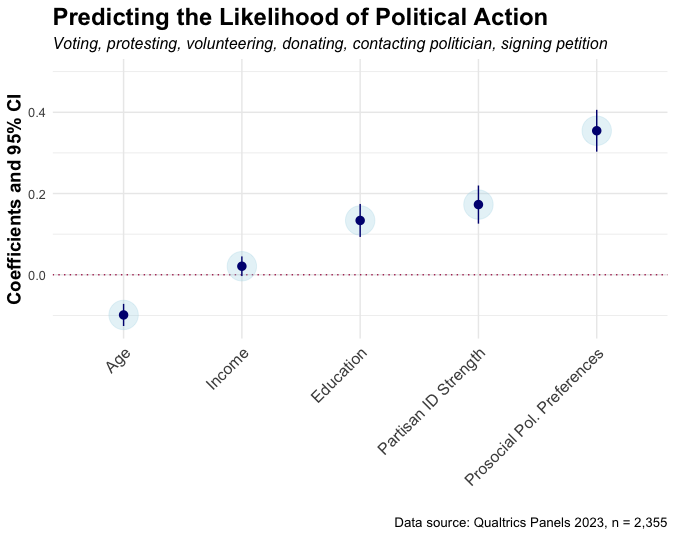

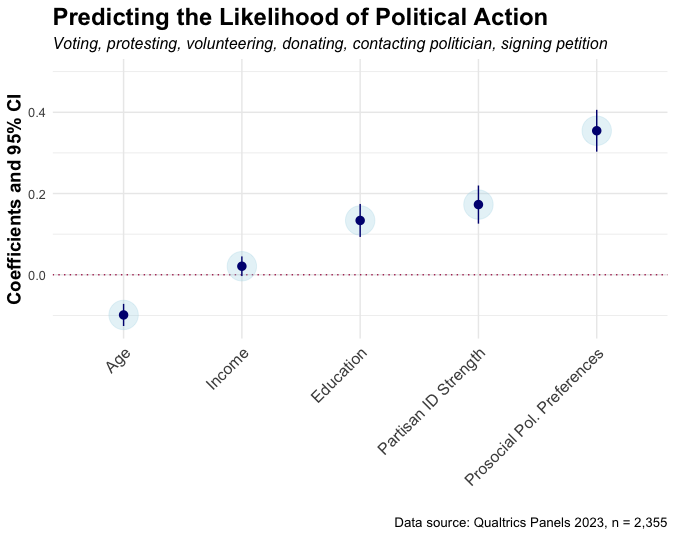

I fielded the prosocial political preferences questions in three separate national surveys of Americans, totaling 4,555 interviews. Across these surveys, I find that Americans on average have moderate to high scores on the scale (0.6 out of a 0-1). Additionally, I find that these political preferences are distinct from existing similar measures, such as group empathy, humanitarianism and egalitarianism, and generalized beliefs about helping others. Using a regression analysis, I find that prosocial political preferences outpace other common predictors, such as an individual’s age, their education, and their level of partisan identity strength.

Palestinians as a Group in Need

Another element of the prosocial politics model is social perception. Americans should be more responsive to a specific group, such as Palestinians, if they perceive that group to be in need– also known as the normative altruism model. Perceptions about need are not created in a vacuum. People rely on social groups to learn norms of helping obligation: the type of groups who should receive help, what the helping should look like, and the social stakes of helping. Public policy, such as welfare, also influences how we perceive the power and deservingness of groups.

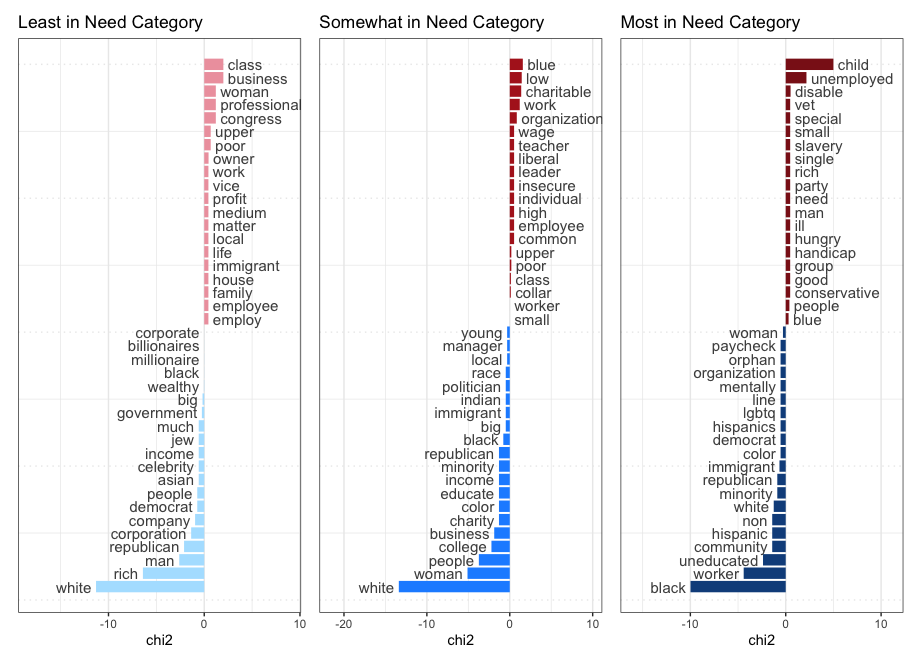

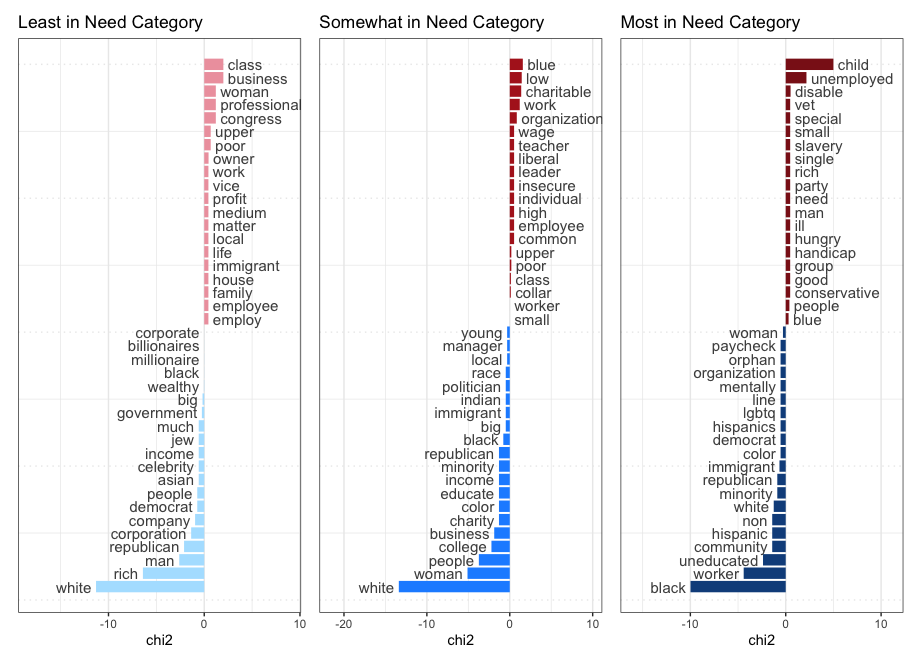

In the United States, political parties heavily shape and are shaped by the social identities of their members. As a result, I expect that partisanship modifies how Americans come to perceive which groups are in need, and which groups are not. To test this part of my theory, I piloted another novel measure called the “Circles of Power and Need,” or CPN for short. The CPN measure solicits a total of 12 text answers from each survey participant, six in Power and six in Need. With a team of undergraduates, I created a coding scheme to capture the breadth and nuance in how Americans describe stratification. We used 23 characteristic categories, and assigned binary values to organize text answers from respondents.

Through this analysis, we find that Americans use multiple dimensions to discuss Power and Need. Three characteristics are the most salient across the CPN measure: Class, Race and Ethnicity, and Institutions. Americans think about power in terms of institutions, parties and ideology groups, corporations, and class. When Americans think about need, they think in terms of class, employment status and racial/ethnic groups.

How Does Partisanship Shape Perceptions?

Democrats are overwhelmingly more likely to discuss groups in need in terms of race, ethnicity, and immigration status, while Republicans more frequently associate need with children, the disabled, and veterans. Republicans and Democrats both associate power and need with class, but Democrats reference ethnoracial and minority groups, such as Black people, White people, Hispanics, immigrants, and LGBTQ+.

The Political Consequences of Prosocial Politics

Images of Palestinian civilians killed as a result of Israeli military aggression have sparked protest, voting campaigns, and political activism. As of early May, 34,000 Palestinians have been killed by Israel’s military campaign in the past six months, including 17,000 children. Millions in Palestine are at risk of starvation as a result of alleged war crimes. Several legal experts refer to Israel’s actions as a genocide, increasing global urgency about assisting civilians at risk.

Public disagreements about the justification of Israel’s actions may not change the mobilizing effect of a steady stream of images of civilians dying, especially groups that are publicly considered more in need. Children, women, healthcare workers, foreign aid workers, educators, emergency responders, and journalists are all categories of people that are usually seen by the public as more deserving of help than other categories of people (e.g., soldiers, elected officials).

Americans protesting for the plight of Palestinians connect their cause to global justice problems like climate change, violence against indigenous populations, racism and policing. The breadth of these causes likely influences prosocial norms for Palestine, especially among youth who may have participated in the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in their adolescence.

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have higher disapproval rates for Biden’s handling of the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza in compared to their older copartisans (81% among 18-34 year olds, compared to 53% among all Democrats). In my dissertation, I also investigate how the absence of prosocial political preferences makes a difference in mobilization among individuals with different political attitudes, or issue positions. Additionally, I qualitatively study the prevalence of helping narratives in how Americans describe their own protest participation in 2020-2021.

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have higher disapproval rates for Biden’s handling of the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza in compared to their older copartisans (81% among 18-34 year olds, compared to 53% among all Democrats). In my dissertation, I also investigate how the absence of prosocial political preferences makes a difference in mobilization among individuals with different political attitudes, or issue positions. Additionally, I qualitatively study the prevalence of helping narratives in how Americans describe their own protest participation in 2020-2021.

Student activists likely have consolidated clear ideas about Palestinians as a group in need of help, and feel morally compelled to assist them in any way they can. According to recent polling from Gall Sigler and Daniel Hopkins, younger Americans express greater sympathy for Palestinians than older Americans. This is one of many political generational divides.

For college students, demanding financial divestment from companies sustaining military action is a tactic with historical precedence. Young student activists are not alone in this conviction. Understanding solidarity activism through the lens of prosocial politics clarifies the puzzle of why so many Americans are overcoming the costs of engaging in political action– especially since protest can be an effective means of recourse for disadvantaged groups to enact political change.

Pro-Palestine activism around the world has brought the suffering of Gazans to the attention of mainstream media, setting an agenda for the upcoming presidential election. Even if campus encampments are dispersed by police, counter-protestors, or administrators, U.S. military support for Israel will likely be a salient issue for many young Americans. Future research should consider how helping others as a political value challenges common understandings of what drives political participation.

Key Takeaways:

- The prosocial politics model offers a new way to understand why people decide to engage in political action.

- Prosocial political preferences, or the extent to which people see helping others as a political value, is a powerful predictor of political action.

- Exploring the nuance in how people conceptualize others in need can clarify situations where people may or may not be driven to action.

- Partisan cues and social norms affect whom we see as people in need. Although class signifies need across parties, Democrats bring up race and ethnicity more than Republicans, who typically mention age groups, such as children or the elderly.

- Through the lens of prosocial politics, we can understand the recent wave of committed activism as motivated by a desire to help Palestinians suffering in Gaza. U.S. military aid to Israel will be a salient issue for Americans in the 2024 presidential election.

Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.

Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.

Tevah Platt, communications specialist for the Center for Political Studies, contributed to the development of this post. Photos from William Lopez and Tevah Platt.

Dec 15, 2023 | Conflict, Policy

As an undergraduate, associate professor Megan Stewart took a class on Middle East politics and became interested in how a political movement, like the Muslim Brotherhood, was providing social services. She pursued that inquiry by going to Egypt herself to do interviews. That was the first field work of what has become her academic expertise—the intersection of political violence and overlapping systems of governance. Her continuing research has taken her to Baalbek in Lebanon to study Hezbollah, as well as to Timor-Leste, Australia, Sweden, Portugal, and the UK.

Stewart, who joined the Ford School faculty in 2022, brings that combination of real-world experience and intellectual acumen to her new role as director of the International Policy Center (IPC). (Former director John Ciorciari is on leave this academic year.)

She has examined Black political leadership in the aftermath of the Civil War and the rise of female innovators in post-WWII America, as well as topics as diverse as land distribution in China, Zimbabwe, Vietnam, Eritrea, and Colombia; the social policies of insurgent groups; and even the implementation of the metric system in revolutionary France. Her research ultimately rests at the nexus of political violence and attempts to radically redistribute social, economic, and political power.

“My motivation has been to find out what is the relationship between redistributive projects and political violence? Under what conditions do political actors attempt challenging and complicated redistributive projects? Under what conditions are redistributive projects successful, and when they fail, why? Is there a particular element that drives it one way or the other?” she explains.

“The Ford School has a real expertise and history of excellence in social policy, which I consider as policy that takes social inequalities seriously. I’d like to think that in the context of civil war and political violence, my research is doing the same.”

Stewart’s understanding of those recent and historic movements, and their successes and failures, can inform new policy on some of the most pressing issues, like how to think about climate change, the role of climate reparations, and the distributive implications thereof. “Climate reparations have the potential to challenge existing distributions of economic power. Because I believe in these programs, I want to know the conditions under which they are likely to be successful. Under what conditions do the policies last? What is the possibility for backlash, especially violent backlash?”

“All of these questions, and almost all forms of political violence, are intimately related to social inequalities. I want to turn to evidence-informed policy when we see exclusionary networks, especially those that use political violence to exclude and subjugate, to learn how they can be changed in meaningful ways.”

She hopes students working with the IPC can answer some of those questions with her trademark combination of ongoing research and experiential learning opportunities.

This content, by Daniel Rivkin, is reposted here with permission from State & Hill, the magazine of the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy.

Megan Stewart joined the Center for Political Studies in 2023. She recently published an intellectual history of the evolution of civil wars research for the 25th anniversary edition of the Journal of Civil Wars. She called this essay the most personal work she has yet written.

Mar 9, 2022 | Conflict, Current Events, International

Post developed by Katherine Pearson

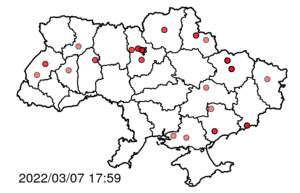

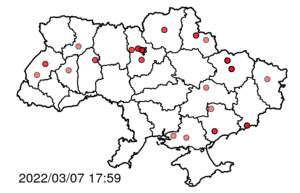

In order to track and share data on events unfolding in Ukraine, Yuri Zhukov, Associate Professor of Political Science and Research Associate Professor at the Center for Political Studies, launched VIINA: Violent Incident Information from News Articles on the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine. VIINA is a near-real time multi-source event data system for the invasion.

“I wanted to make these data available immediately because media sites in both countries are already being shut down, due to either censorship (in Russia) or military operations (in Ukraine),” said Zhukov. “It is thus essential that researchers have access to information about the war, as reported across media organizations and other actors in the information space.” While different media cover different types of events, VIINA’s multi-source approach will capture a more accurate picture of events as they unfold.

This platform allows researchers to access data based on news reports from Ukrainian and Russian media, which have been geocoded and classified into standard conflict event categories through machine learning.

VIINA is freely available for use by students, journalists, policymakers, and researchers. Using an automated web scraping routine that runs every 6 hours, VIINA extracts the text of news reports published by each source and their associated metadata, including publication time and date, web urls. GIS-ready data can be downloaded from VIINA, with temporal precision down to the minute.

VIINA draws on news reports from a variety of Ukrainian and Russian news providers. Data sources currently include news wires, TV stations, newspapers, and online publications in both countries. Zhukov plans to expand these sources as the conflict unfolds, to include OSINT social media feeds and other key sources. The set of sources may also change as the war unfolds — due to interruptions to journalistic activity from military operations, cyber attacks, and state censorship, as well as the availability of new data from other information providers.

VIINA: Violent Incident Information from News Articles on the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine.

Sep 1, 2016 | APSA, Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Catherine Allen-West in coordination with Michael Robbins.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Passive Support for the Islamic State: Evidence from a Survey Experiment” was a part of the session “Survey and Laboratory Experiments in the Middle East and North Africa” on Thursday, September 1, 2016.

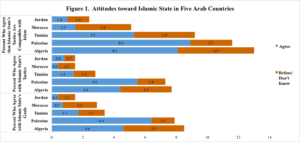

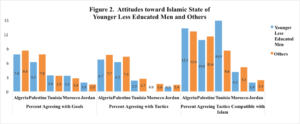

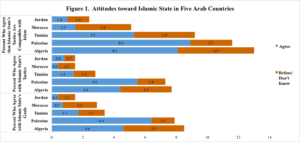

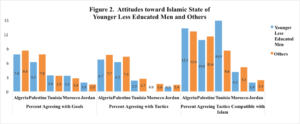

On Thursday morning at APSA 2016, Michael Robbins, Amaney Jamal and Mark Tessler presented work which explores levels of support for the Islamic State among Arabs, using new data from the Arab Barometer. The slide set used in their presentation can be viewed here: slides from Robbins/Jamal/Tessler presentation

Their results show that among the five Arab countries studied (Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, Palestine and Algeria) there is very little support for the tactics used by Islamic State.

Furthermore, even among Islamic State’s key demographic – younger, less-educated males – support remains low.

For a more elaborate discussion of this work and the above figures, please see their recent post in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog, “What do ordinary citizens in the Arab world really think about the Islamic State?”

Mark Tessler is the Samuel J. Eldersveld Collegiate Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan. Michael Robbins is the director of the Arab Barometer. Amaney A. Jamal is the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton University and director of the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice.

Apr 4, 2016 | Conflict, International

Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Christian Davenport.

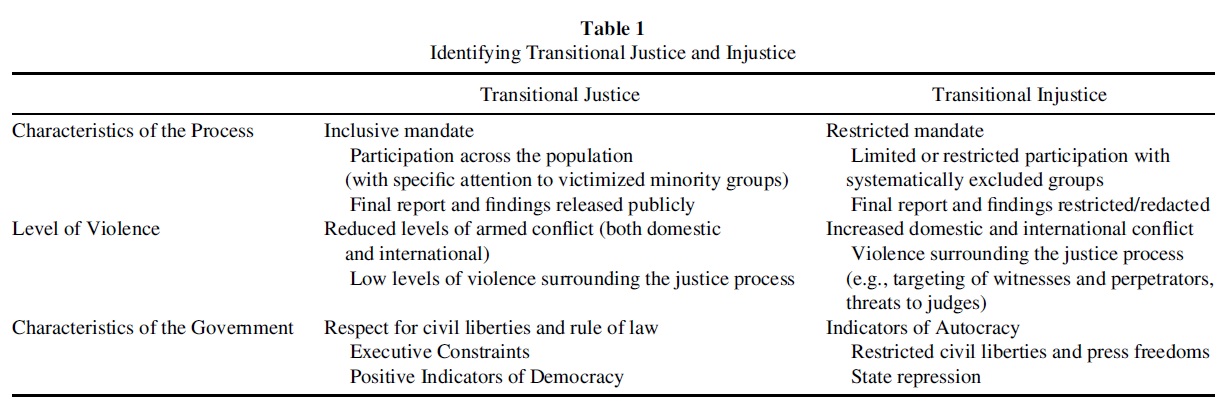

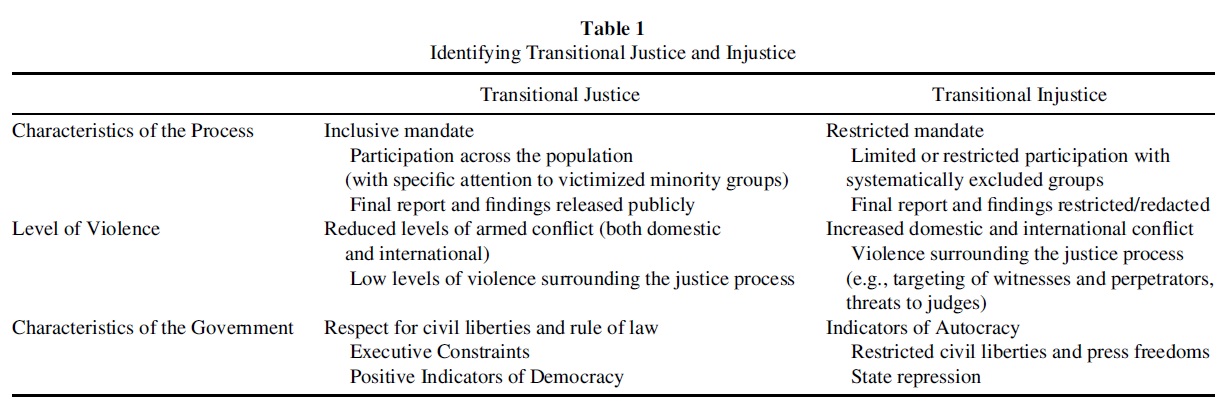

Department of Political Science Professor and Center for Political Studies faculty member Christian Davenport’s latest work examines transitional justice – judicial and non-judicial actions implemented by governments to deal with legacies of human rights abuses. These actions can typically include criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations, and various kinds of institutional reforms.

In Transitional Injustice: Subverting Justice in Transition and Postconflict Societies, published in the Journal of Human Rights, Davenport and Cyanne Loyle, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Indiana University, coin the term transitional injustice to describe governments that implement transitional justice without maintaining interest in truth, peace, or democracy. Instead, their intention is to promote denial and forgetting, violence, and legitimize authoritarianism.

The normative perspective of transitional justice assumes that legal processes following political conflict are implemented with the goal of reconciliation, peace, and democratization. It is assumed that “good” processes will lead to “good” outcomes. However, this assumption makes it possible for governments to hide behind transitional justice using similar legal institutions to advance detrimental aims. Davenport and Loyle argue that governments can use trials, truth commissions and amnesty without maintaining an interest in these goals, but rather to promote transitional injustice, i.e. denial, violence, and legitimizing state repression. Transitional injustice is particularly problematic for those interested in promoting justice processes because it reveals how institutions can be subverted for different purposes, often with international consent.

The article not only provides conceptual clarity on identifying differences but also provides indicators by which policy makers and scholars can determine if transitional injustice is taking place. In particular, policy makers can identify transitional injustice by relying on three key dimensions: (1) characteristics of the process, (2) levels of violence in the postconflict society, and (3) characteristics of the government (Table 1). These components allow government intentions and the potential for subversion of justice to be evaluated.

First, the degree of openness of the process is an indicator of the objectives of the government and the possibility for positive outcomes from the process. One could gauge the promotion or subversion of truth-telling by the degree to which distinct actors are integrated into the justice process, given an opportunity to participate, to draft, review and edit relevant decisions, as well as veto aspects of the process. Transitional justice should have a broad mandate incorporating all types of violations experienced during the conflict. Transitional injustice, however, reveals itself as a more closed process with a limited mandate and exclusion of certain individuals and groups.

The second indicator is the level of violence surrounding the process and the country. While violent events often linger in postconflict societies, the presence of transitional justice should lead to reduced levels of violence in the society overall. Transitional injustice however, is accompanied by violence internationally, domestically, and surrounding the process itself.

Third, characteristics of the government can be assessed by the level of democracy and the country’s present trajectory. Breaking from a past autocratic regime does not ensure that the new regime will be more democratic. Rather, the intentions of the regime should be assessed through institutional and behavioral indicators of democracy. The degree to which a justice process legitimates a democracy through open and frequent elections, diverse and representative political parties, and autonomous institutions is a valuable metric for understanding the general intent of those involved. Transitional justice should be accompanied by growing levels of democracy, while transitional injustice will accompany autocracy.

To more specifically illustrate how to identify transitional injustice, the article examines post-genocide Rwanda. On the surface, it appears that Rwanda’s approach to justice supports the normative aims of transitional justice. The Rwandan approach combines international, national, and local justice processes with the stated goals of truth and reconciliation, peace, and democracy. However, critics have called into question the ability of this justice package to accomplish those goals. Instead, it is being revealed that elements of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, national courts, and local justice processes have been used by the Rwandan government to promote denial, renewed violence, and the legitimization of an autocratic regime.

Regarding the openness of the process, the first dimension of transitional injustice, the space for justice in post-genocide Rwanda has been constricted through the support of targeted remembering, state-sanctioned scripted truths, and restricted access to justice. Instead of addressing all forms of conflict in Rwanda, the current justice package concentrates only on violence committed during the genocide. This strategy aims to direct attention to the successes of the government, namely ending the genocide, and away from its failures, mainly human rights violations and civilian massacres during the civil war and following the 1994 political transition.

Turning to the level of violence surrounding the process, far from reducing violence, the Rwandan approach to justice allows the government to increase domestic violence and international conflict. Violence has been a persistent component of the post-1994 Rwandan state, as in the aftermath of the genocide, a number of people were accused, tried and executed in a short period of time. By 2000, 348 people convicted of genocide crimes through the national courts were sentenced to death (Schabas, 2009), while the procedural fairness of many of those trials is questioned (Amnesty International, 2007). There has also been violence surrounding the justice processes themselves. In 2007 alone, the US State Department recorded 324 incidents of violence related to local justice processes, including killings of genocide survivors (US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2008). While the government has officially denounced the violence, it has been reluctant or unable to stop it.

The final dimension of transitional injustice, characteristics of the government, provides an example of the Rwandan justice system working to consolidate an authoritarian regime and restrict political participation. The Rwandan government is a far cry from a functioning democracy. While elections have been held, their validity has been questioned and the lack of a viable opposition party has essentially made the country a single-party state (Reyntjens, 2004; Davenport, 2007). Freedom House (2007) has characterized elections as “marred by bias and intimidation which precluded any genuine challenge to the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)”.

Attempts to launch rival political parties have been met with intimidation and, in some instances, violence. The restriction of viable political alternatives to President Kagame’s RPF has limited the electoral power of individual citizens. In the 2010 presidential election, three opposition candidates were excluded from the ballot and Paul Kagame was reelected by 93% of the vote.

In conclusion, Rwanda claims to support domestic and international efforts to collect information about what happened, to communicate the findings, and capture and punish those who were involved in previous violent action. Through these efforts, the government has argued that it will advance truth and reconciliation, prevent violence and facilitate democratization. Unfortunately, by concealing political motivations in the obstruction of justice proceedings and engaging in violent activity, the Rwandan government is doing irreparable damage to the development of truth, reconciliation, rule-of-law, and democracy. In order to acknowledge and challenge this subversion, the international community must recognize the ability of justice institutions to be used for less democratic aims. This research therefore aims to provide skepticism regarding the goals associated with transitional justice as well as indicators to evaluate the potential subversion of relevant processes.

References:

Amnesty International. (2007). Truth, justice and reparation: Establishing an effective truth commission. AI Index: POL 30/009/2007. Available: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4678de4a2.html.

Davenport, Christian. (2007). State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Freedom House. (2007). Countries at a Crossroad: Rwanda. Available: https://freedomhouse.org/report/countries-crossroads/2007/rwanda.

Reyntjens, Filip. (2004). Rwanda, ten years on: From genocide to dictatorship. African Affairs,103, 177-210.

Schabas, William A. (2009). Post-genocide justice in Rwanda. In After Genocide: Transitional Justice, Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Reconciliation in Rwanda and Beyond, Phil Clark and Zachary D. Kaufman (eds.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Nov 3, 2015 | Conflict, Current Events, International, Uncategorized

Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Yuri Zhukov.

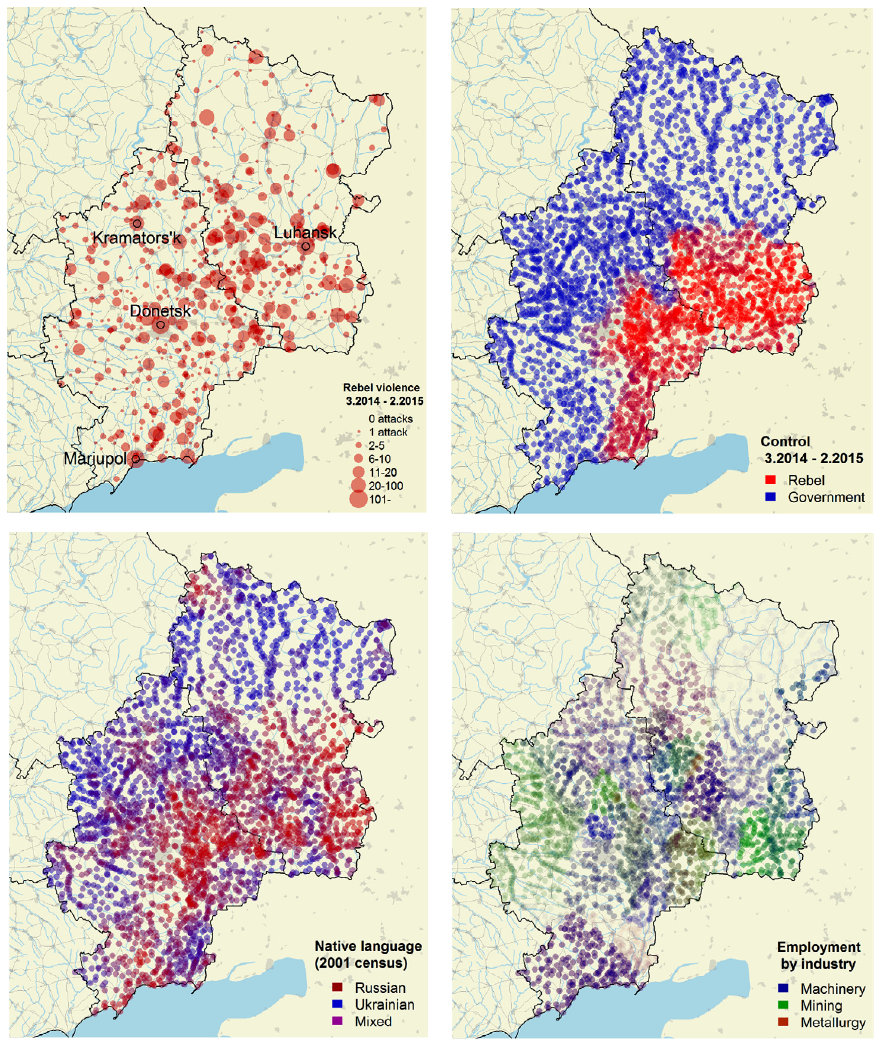

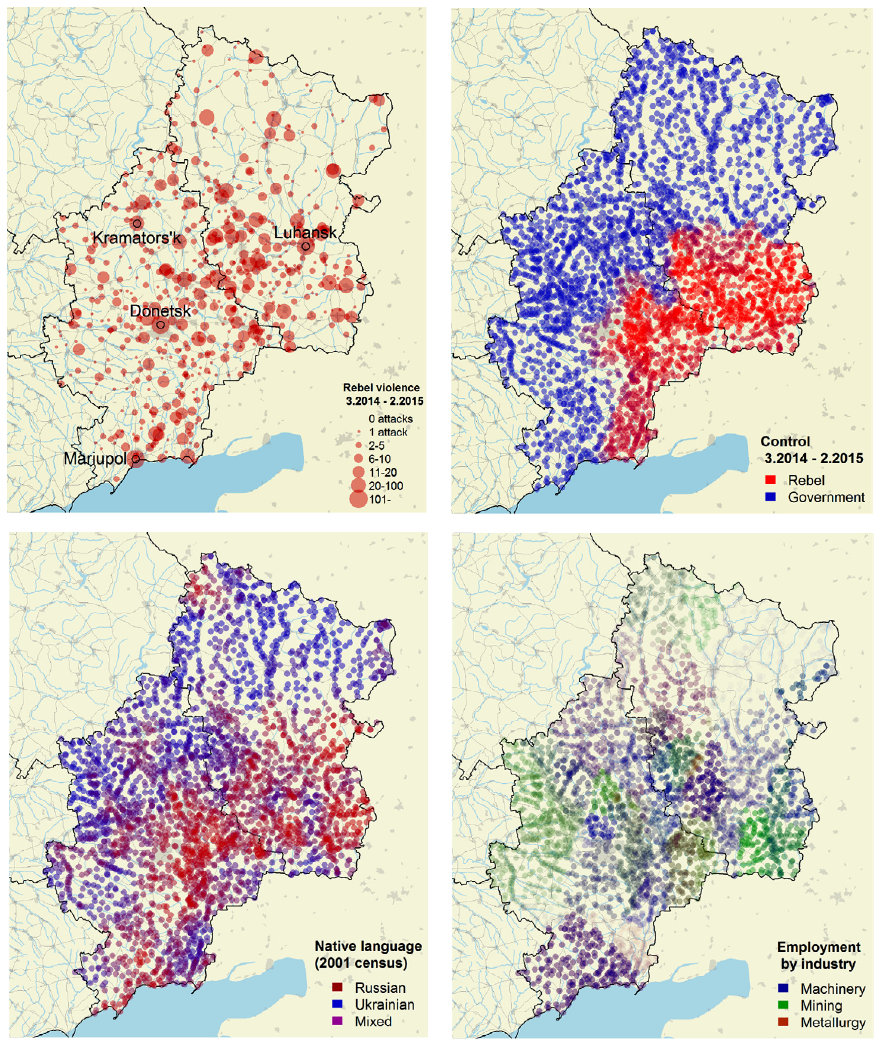

In March and April 2014, angry mobs and armed men stormed administrative buildings and police stations in eastern Ukraine. Waving Russian flags and condemning the post-revolutionary government in Kyiv as an illegal junta, the rebels proclaimed the establishment of ‘Peoples’ Republics’ of Donetsk and Luhansk, and organized a referendum on independence. Despite initial fears that the uprising might spread to other provinces, the rebellion remained surprisingly contained. While 61% of municipalities in Donetsk and Luhansk fell under rebel control during the first year of the conflict, just 20% experienced any rebel violence. What explains these local differences in rebellion across eastern Ukraine? Why have some towns remained under government control while others slipped away? Why might two municipalities in the same region experience different levels of separatist activity?

Yuri Zhukov

The latest research by Yuri Zhukov, faculty member in the Center for Political Studies and Assistant Professor of Political Science, uses new micro-level data on violence and economic activity in eastern Ukraine to examine these questions. In the paper “Trading hard hats for combat helmets: The economics of rebellion in eastern Ukraine” (forthcoming in the Journal of Comparative Economics) Zhukov evaluates two prominent explanations on the causes and dynamics of civil conflict in eastern Ukraine: ethnicity and economics.

Identity-based explanations expect conflict to be more likely and more intense in areas where ethnic groups are geographically concentrated. According to this view, the geographic concentration of an ethnolinguistic minority – in this case, Russians or Russian speaking Ukrainians – helps local rebels overcome collective action problems, while attracting an influx of fighters, weapons and economic aid from co-ethnics in neighboring states.

According to economic explanations, as real income from less risky legal activities declines relative to income from rebellious behavior, participation in the rebellion is expected to rise. This framework maintains that violence should be most pervasive in areas potentially harmed by trade openness with the EU, austerity and trade barriers with Russia.

Zhukov finds that local economic factors are much stronger predictors of rebel violence and territorial control than Russian ethnicity or language. Pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine are “pro-Russian” not because they speak Russian, but because their economic livelihood depends on trade with Russia.

The study uses new micro-level data on violence, ethnicity and economic activity in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, to understand how these two explanations are related to rebel violence and territorial control. The spatial units are 3037 municipalities (i.e. cities, towns, villages) in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. For each municipality, Zhukov estimated the proportion of the local labor force employed in three industries: machine-building (which is heavily dependent on exports to Russia), metals (less dependent on Russia, and a potential beneficiary of increased trade with the European Union), and mining (vulnerable to International Monetary Fund-imposed austerity and cuts in state-subsidies). He also calculated the proportion of Russian speakers in each locality.

Rebel violence data are based on human-assisted machine coding of incident reports from multiple sources, including Ukrainian and Russian news agencies, government and rebel press releases, daily ‘conflict maps’ released by both sides, and social media news feeds. This yielded 10,567 unique violent events in the Donbas, at the municipality level, recorded between the departure of President Viktor Yanukovych in February 2014 and the second Minsk ceasefire agreement of February 2015. To determine territorial control, particularly whether a populated place was under rebel or government control on a given day, Zhukov used three sources: official daily situation maps publicly released by Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council (RNBO), daily maps assembled by the pro-rebel bloggers ‘dragon_first_1’ and ‘kot_ivanov’, and Facebook posts on rebel checkpoint location.

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).

By contrast, ethnicity and language had no discernible impact on rebel violence. Municipalities with large Russian-speaking populations were more likely to fall under rebel control, but only where economic dependence on Russia was relatively low. In other words, ethnicity only had an effect where economic incentives for rebellion were weak.

The seemingly rational economic self-interest at the heart of the conflict stands in sharp contrast with the staggering costs of war. In the twelve months since armed men began storming government buildings in the Donbas, over 6000 people have lost their lives, and over a million have been displaced. Regional industrial production fell by 49.9% in 2014, with machinery exports to Russia down by 82%.Suffering heavy damage from shelling, many factories have closed. With airports destroyed, railroad links severed and roads heavily mined, a previously export-oriented economy has found itself isolated from the outside world.

References:

2001 Ukrainian Census (State Committee on Statistics of Ukraine, 2001).

Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis database (Bureau van Dijk Electronic Publishing, 2015).

Segodnya, 2015. Ekonomika donetskoy oblasti v upadke iz-za voyny – gubernator kikhtenko. [Donetsk region’s economy in stagnation because of the war – Governor Kikhtenko]. Segodnya.

Stasenko, M., 2014. Novaya ekonomika ukrainy budet stroit’sya bez rossii i donbassa [Ukraine’s new economy will be built without Russia or the Donbas]. Delo.ua.

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting provocative slogans. Beyond tents and sleeping areas, many encampments feature Liberation Libraries, communal art-making, and worship spaces for Jewish and Muslim participants. At the University of Michigan, students from the TAHRIR coalition have organized daily programming including teach-ins, external speaker events, documentary screenings, and broader community education initiatives.

Still, there is abundant evidence to suggest that encampments represent much more than just riled up college students chanting provocative slogans. Beyond tents and sleeping areas, many encampments feature Liberation Libraries, communal art-making, and worship spaces for Jewish and Muslim participants. At the University of Michigan, students from the TAHRIR coalition have organized daily programming including teach-ins, external speaker events, documentary screenings, and broader community education initiatives.

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have higher disapproval rates for Biden’s handling of the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza in compared to their older copartisans (81% among 18-34 year olds, compared to 53% among all Democrats). In my dissertation, I also investigate how the absence of prosocial political preferences makes a difference in mobilization among individuals with different political attitudes, or issue positions. Additionally, I qualitatively study the prevalence of helping narratives in how Americans describe their own protest participation in 2020-2021.

Prosocial politics may shed some light on why pro-Palestinian activism is so prevalent among young students, who are more likely to align themselves with the Democratic party, but have higher disapproval rates for Biden’s handling of the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza in compared to their older copartisans (81% among 18-34 year olds, compared to 53% among all Democrats). In my dissertation, I also investigate how the absence of prosocial political preferences makes a difference in mobilization among individuals with different political attitudes, or issue positions. Additionally, I qualitatively study the prevalence of helping narratives in how Americans describe their own protest participation in 2020-2021.  Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.

Eugenia Quintanilla is an American Politics doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, and the recipient of the Garth Taylor Dissertation Award for Public Opinion– an ISR Next Generation award granted by the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research. She broadly studies political psychology, race and ethnic politics, and public opinion. Her current scholarship investigates questions about how politics and the desire to help others intersect to influence political behavior. She also studies American attitudes about wealth inequality, Latino political socialization, and racial attitudes.