Nov 3, 2015 | Conflict, Current Events, International, Uncategorized

Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Yuri Zhukov.

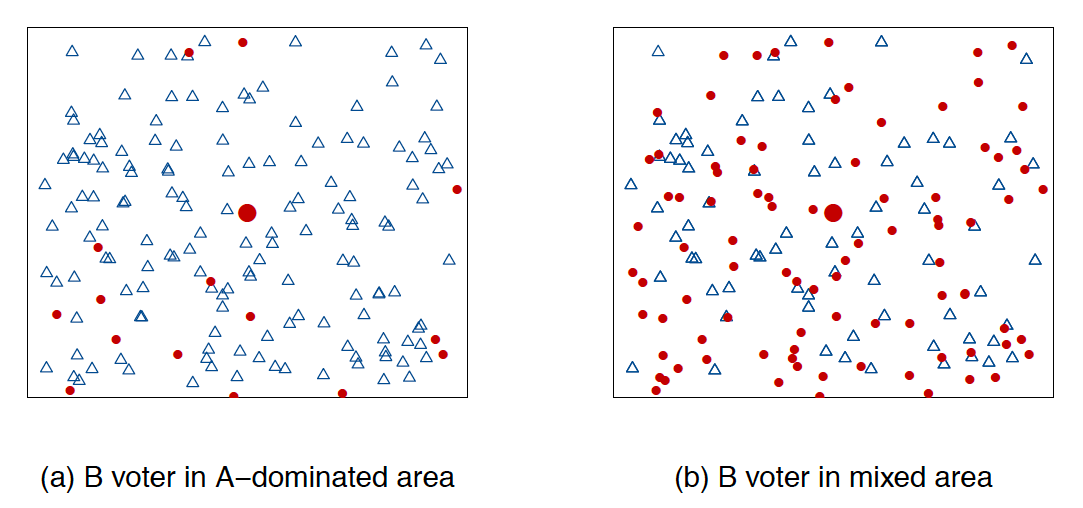

In March and April 2014, angry mobs and armed men stormed administrative buildings and police stations in eastern Ukraine. Waving Russian flags and condemning the post-revolutionary government in Kyiv as an illegal junta, the rebels proclaimed the establishment of ‘Peoples’ Republics’ of Donetsk and Luhansk, and organized a referendum on independence. Despite initial fears that the uprising might spread to other provinces, the rebellion remained surprisingly contained. While 61% of municipalities in Donetsk and Luhansk fell under rebel control during the first year of the conflict, just 20% experienced any rebel violence. What explains these local differences in rebellion across eastern Ukraine? Why have some towns remained under government control while others slipped away? Why might two municipalities in the same region experience different levels of separatist activity?

Yuri Zhukov

The latest research by Yuri Zhukov, faculty member in the Center for Political Studies and Assistant Professor of Political Science, uses new micro-level data on violence and economic activity in eastern Ukraine to examine these questions. In the paper “Trading hard hats for combat helmets: The economics of rebellion in eastern Ukraine” (forthcoming in the Journal of Comparative Economics) Zhukov evaluates two prominent explanations on the causes and dynamics of civil conflict in eastern Ukraine: ethnicity and economics.

Identity-based explanations expect conflict to be more likely and more intense in areas where ethnic groups are geographically concentrated. According to this view, the geographic concentration of an ethnolinguistic minority – in this case, Russians or Russian speaking Ukrainians – helps local rebels overcome collective action problems, while attracting an influx of fighters, weapons and economic aid from co-ethnics in neighboring states.

According to economic explanations, as real income from less risky legal activities declines relative to income from rebellious behavior, participation in the rebellion is expected to rise. This framework maintains that violence should be most pervasive in areas potentially harmed by trade openness with the EU, austerity and trade barriers with Russia.

Zhukov finds that local economic factors are much stronger predictors of rebel violence and territorial control than Russian ethnicity or language. Pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine are “pro-Russian” not because they speak Russian, but because their economic livelihood depends on trade with Russia.

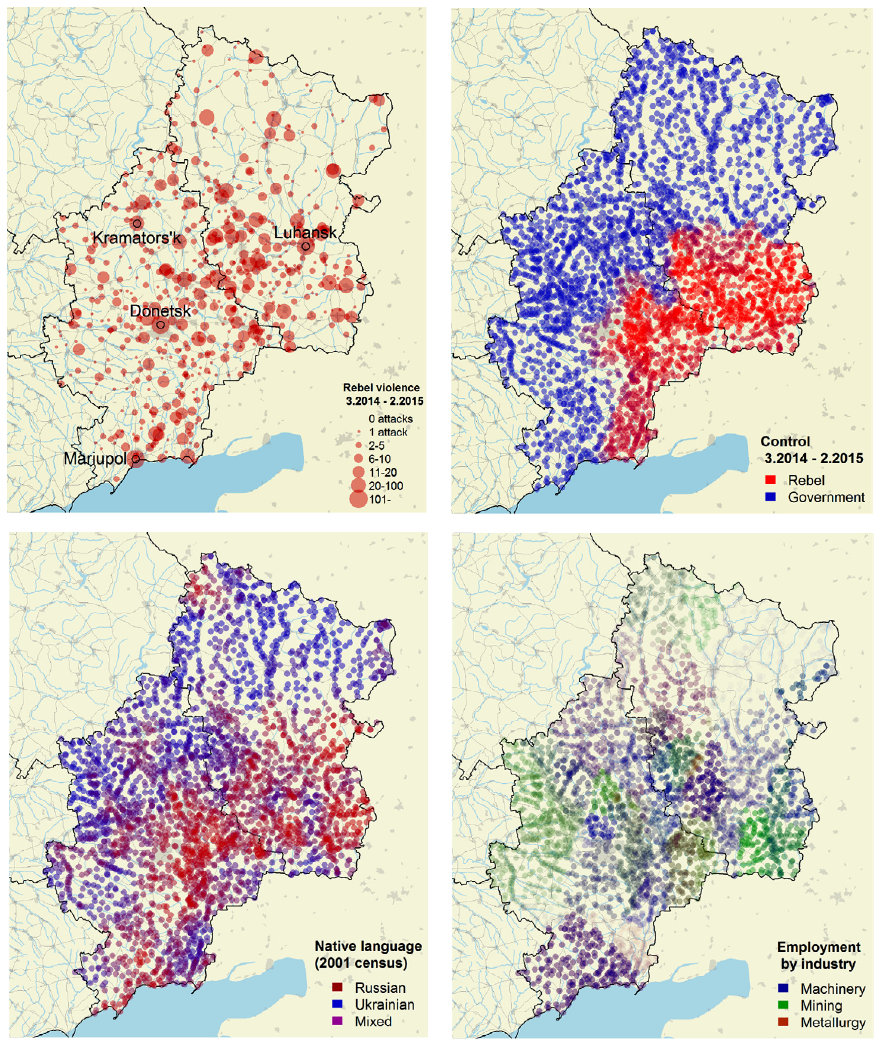

The study uses new micro-level data on violence, ethnicity and economic activity in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, to understand how these two explanations are related to rebel violence and territorial control. The spatial units are 3037 municipalities (i.e. cities, towns, villages) in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. For each municipality, Zhukov estimated the proportion of the local labor force employed in three industries: machine-building (which is heavily dependent on exports to Russia), metals (less dependent on Russia, and a potential beneficiary of increased trade with the European Union), and mining (vulnerable to International Monetary Fund-imposed austerity and cuts in state-subsidies). He also calculated the proportion of Russian speakers in each locality.

Rebel violence data are based on human-assisted machine coding of incident reports from multiple sources, including Ukrainian and Russian news agencies, government and rebel press releases, daily ‘conflict maps’ released by both sides, and social media news feeds. This yielded 10,567 unique violent events in the Donbas, at the municipality level, recorded between the departure of President Viktor Yanukovych in February 2014 and the second Minsk ceasefire agreement of February 2015. To determine territorial control, particularly whether a populated place was under rebel or government control on a given day, Zhukov used three sources: official daily situation maps publicly released by Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council (RNBO), daily maps assembled by the pro-rebel bloggers ‘dragon_first_1’ and ‘kot_ivanov’, and Facebook posts on rebel checkpoint location.

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).

By contrast, ethnicity and language had no discernible impact on rebel violence. Municipalities with large Russian-speaking populations were more likely to fall under rebel control, but only where economic dependence on Russia was relatively low. In other words, ethnicity only had an effect where economic incentives for rebellion were weak.

The seemingly rational economic self-interest at the heart of the conflict stands in sharp contrast with the staggering costs of war. In the twelve months since armed men began storming government buildings in the Donbas, over 6000 people have lost their lives, and over a million have been displaced. Regional industrial production fell by 49.9% in 2014, with machinery exports to Russia down by 82%.Suffering heavy damage from shelling, many factories have closed. With airports destroyed, railroad links severed and roads heavily mined, a previously export-oriented economy has found itself isolated from the outside world.

References:

2001 Ukrainian Census (State Committee on Statistics of Ukraine, 2001).

Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis database (Bureau van Dijk Electronic Publishing, 2015).

Segodnya, 2015. Ekonomika donetskoy oblasti v upadke iz-za voyny – gubernator kikhtenko. [Donetsk region’s economy in stagnation because of the war – Governor Kikhtenko]. Segodnya.

Stasenko, M., 2014. Novaya ekonomika ukrainy budet stroit’sya bez rossii i donbassa [Ukraine’s new economy will be built without Russia or the Donbas]. Delo.ua.

Oct 29, 2015 | International, Law, Profile

Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Barbara Koremenos.

Barbara Koremenos, Center for Political Studies faculty member and Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan has recently begun a Visiting Research Fellowship at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame. The Kroc Institute is devoted to the study of the causes of violent conflict and strategies for sustainable peace. She was awarded the Fellowship to spend the 2015-2016 year studying the relationship between Islamic states and international law, and to examine how this affects Islamic states’ participation in international agreements and ultimately the peaceful resolution of differences.

Barbara Koremenos, Center for Political Studies faculty member and Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan has recently begun a Visiting Research Fellowship at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame. The Kroc Institute is devoted to the study of the causes of violent conflict and strategies for sustainable peace. She was awarded the Fellowship to spend the 2015-2016 year studying the relationship between Islamic states and international law, and to examine how this affects Islamic states’ participation in international agreements and ultimately the peaceful resolution of differences.

Koremenos was inspired by looking at a random sample of international agreements in the issue areas of economics, environment, human rights, and security drawn from the United Nations Treaty Series (UNTS), which is by far the most popular place to register international agreements. She was struck by the fact that not a single agreement in her sample was composed solely of Islamic states. Within the sample, Egypt participated in the most agreements (25 agreements) while Oman had the lowest participation rate (seven agreements). With the exception of Malaysia, every other state in the sample participated in at least as many (usually more) human rights agreements than agreements in any of the other three issue areas. Within the sample, Lebanon participated more than any other Islamic state in environmental agreements at a quite low number of five.

Even more striking, participation in multilateral agreements seemed to far outweigh participation in bilateral agreements, even though bilateral cooperation is more prevalent worldwide when looking at the entire UNTS population. This is also true when looking at the sample featured in Professor Koremenos’ Continent of International Law (COIL) research program.

In the UNTS sample, over half of the Islamic states participated in no bilateral agreements; Egypt was the state that participated in the most bilateral agreements (six agreements) followed by Oman and Indonesia at two bilateral agreements each.

Koremenos will use her fellowship this year to examine whether:

- Islamic states simply participate in fewer international agreements than non-Islamic states

- With respect to participation in international agreements, there is variation within Islamic states that can be explained by whether Shari’a is officially adopted in a state’s constitution

- Islamic states participate in international agreements that are not registered with the UNTS;

- Islamic states participate in relatively more informal international agreements

Answers to these questions will give a sense of the amount of “failed cooperation” in those states – that is, cooperation that is precluded because certain institutional design tools, that might be key to solving the cooperation problems facing states, are disallowed by Shari’a Law – and, to begin to suggest larger relationships that might impact key factors in the world of peace and conflict like economic growth.

Sep 5, 2015 | Elections, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Walter Mebane.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Election Frauds, Postelection Legal Challenges and Geography in Mexico,” was a part of the session “Detecting and Concealing Patterns in Data” on Saturday September 5th, 2015.

Political Science and Statistics Professor and Center for Political Studies faculty member Walter Mebane previously examined electoral fraud in Russia. Professor Mebane, in collaboration with Research Assistant Jonathan Wall, now turns his focus to Mexico and the Presidential elections of 2006 and 2012.

This new research by Mebane and Wall investigates if the numbers of casillas (i.e. ballot boxes) and votes challenged and nullified in Mexico reflect political strategies or genuine election irregularities. In the 2006 elections in Mexico, nullification petitions by runners up were filed against 21% of ballot boxes (27,109/130,788), even though only .56% of votes (237,736/41,791,322) were actually nullified. Similarly, in the 2012 elections, 22% of ballot boxes (32,151/143,132) were challenged and .38% of votes nullified (184,725/49,087,466).

Mebane and Wall examine how the types of nullification claims relate to ballot-box level measures of election fraud and whether the reasons cited for the challenges are uniform across the two elections and/or geography. That is, are complaints geographically clustered or does a complaint depend on geographically clustered frauds?

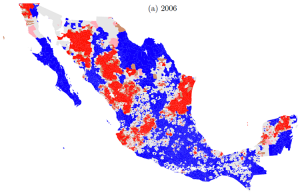

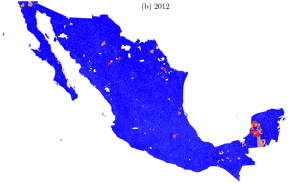

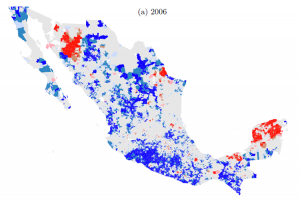

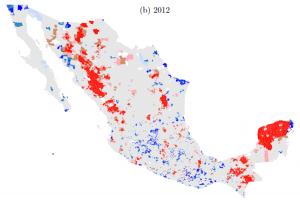

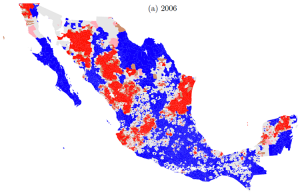

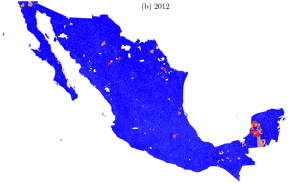

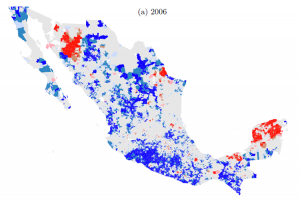

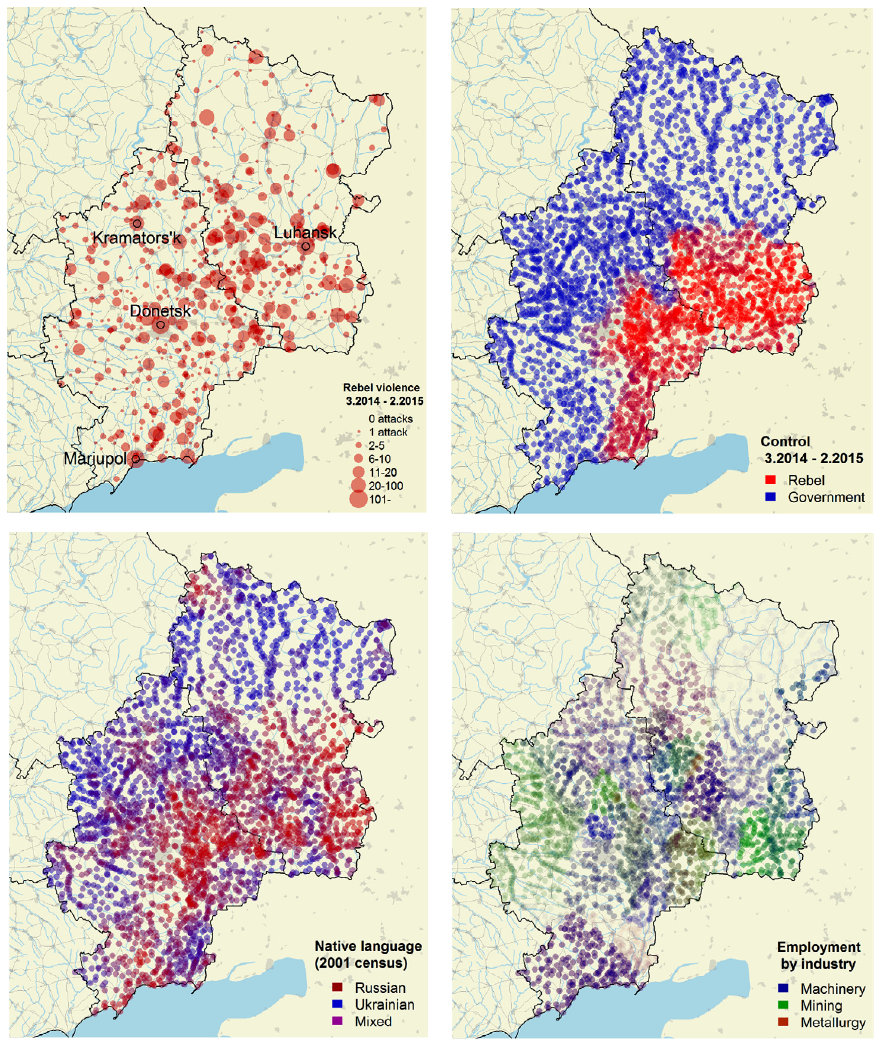

Ballot-box level measures of election fraud are estimated using casilla vote count data. Hotspot analysis is used to show how nullification petition challenges to casillas are distributed across geography. This technique identifies which locations have local means that are higher than the overall average values and which have local means that are lower than the overall average. A redder color indicates a cluster of locations with higher than average values, and a bluer color indicates a cluster of locations with lower than average values. Grey indicates a cluster of locations that does not differ significantly from the overall mean.

Figure 1 represents nullification complaints of type corresponding to willful misconduct or error in the vote count in the two Presidential elections, and Figure 2 represents incremental fraud probabilities for nullification complaints. Comparing Figure 2 to Figure 1 indicates that the pattern of geographic clustering for the incremental fraud probabilities does not correspond well with the pattern for nullification complaints.

Figure 1: Nullification complaints of type corresponding to willful misconduct or error in the vote count, Mexico, 2006 and 2012 Presidential election Casillas.

Seccion (precint) geographic cluster hotspots

Figure 2: Incremental fraud, Mexico, 2006 and 2012 Presidential election casillas.

Seccion (precint) geographic cluster hotspots

In 2006 there are more widespread regions with clusters of casillas having above average frequencies of complaints than there are regions in which there are clusters of casillas with above average incremental fraud probability values. Some of the above average type clusters overlap with above average incremental fraud clusters, but more than half do not. In 2012 on the other hand, we observe the opposite. Clusters of casillas with above average incremental fraud probabilities are much more prevalent than are clusters of casillas with above average frequencies of complaints.

Such patterns indicate that it is unlikely that the relationship between incremental fraud probabilities and the incidence of complaints are positively related. This therefore suggests that the occurrence of nullification petitions is related to the strategic and tactical incentives of political parties.

To read the full paper please visit: https://drive.google.com/open?id=0By8J0EDg6IC3MDgxOWlUVGdfakE

Sep 3, 2015 | International

Post developed by Linda Kimmel in coordination with Elisabeth Gerber.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Mobilizing or Demobilizing Political Participation,” was a part of session “The Public Policy Process in Comparative Perspective” on Thursday September 3rd, 2015.

Sustainable development (SD) policies seek to shape economic and environmental behavior by providing households with benefits, rewards and incentives. But does engagement in SD interventions change individuals’ propensities to engage in political activities? This is the question Center for Political Studies faculty members Arun Agrawal and Elisabeth Gerber, and their colleague Ashwini Chhatre of the Indian School of Business, seek to answer.

Sustainable development (SD) policies seek to shape economic and environmental behavior by providing households with benefits, rewards and incentives. But does engagement in SD interventions change individuals’ propensities to engage in political activities? This is the question Center for Political Studies faculty members Arun Agrawal and Elisabeth Gerber, and their colleague Ashwini Chhatre of the Indian School of Business, seek to answer.

Agrawal, Chhatre, and Gerber note that in new and emerging democracies the challenges of political participation are daunting due to such factors as a lack of education and weak democratic traditions. Can the skills, resources, and experiences gained through participating in SD interventions transfer to the political sphere by lowering barriers? Or, does participation in an SD intervention create additional barriers?

The authors test two hypotheses, one based on social choice theory and the other on resource theory on data collected in a SD intervention in Himachal Pradesh state in northern India, the Mid-Himalayan Watershed Development Project. The project sought to improve the livelihoods of poor households, conserve natural resources, and increase local governance capacity. Participating panchayats (a local government unit) received benefits to enhance residents’ incomes and reduce their dependency on forest resources. In exchange, participants were required to attend information meetings and participate in environmental education training.

Argrawal, Chhatre and Gerber selected five participating panchayats (treatment group) and five matched non-participating panchayats (control group). One member of each household was selected to complete a pre- and post-treatment survey. Key questions included measures of engagement with the SD project and two measures of political participation: (1) days campaigning in local panchayat elections and (2) number of times attending gram sabha meetings (essentially town hall meetings).

Average estimated treatment effect (ATE) is measured as the difference between paired treatment and control respondents in their change in behavior (number of meetings attended and days campaigning) between 2006 (pre-treatment) and 2011 (post-treatment). When respondents in treatment panchayats are compared to those from control panchayats (Table 1, first row), there is a negative ATE both for days campaigning and attending gram sabha meetings, indicating respondents in treatment panchayats became less likely to spend days campaigning and attending meetings than those in control panchayats. Thus, the project seems to demobilize political behavior.

When the analysis is limited to comparing those who actually participated in the project to their counterparts in control panchayats (Table 1, second row), the results differ, with those who participated in the project becoming more likely to attend more gram sabha meetings.

Table 1: Effect of Project on Campaigning and Attending Meetings, Average Treatment Effects with Alternative Treatments. N=1432

| |

Days Campaigning |

Attending Gram Sabha |

| Treatment |

ATE |

ATE |

| Project Village |

-1.57*** |

-0.16* |

| Participation |

-1.51*** |

0.45*** |

*p<.10, **p<.05, ***p<.01, two-tailed test

When the authors reran the data limiting comparison respondents to those who lived in treatment villages but did not participate (Table 2), they found that those who participated in at least one project activity (Table 2, first row) and in each of three types of activities (Table 2, second through fourth row) became more likely to attend gram sabha meetings and to spend more days campaigning than their neighbors who did not.

Table 2: Effect of Project on Campaigning and Attending Meetings, Average Treatment Effects Comparing Respondents within Treatment Villages with Alternative Treatments. N=799

| |

Days Campaigning |

Attending Gram Sabha |

| Treatment |

ATE |

ATE |

| Participation |

0.99** |

1.22*** |

| Attended environmental education Meetings |

0.94** |

1.55*** |

| Received material benefits |

1.16** |

0.72** |

| Participated in construction of small-scale public good |

0.86 |

1.49*** |

*p<.10, **p<.05, ***p<.01, two-tailed test

But why do those who directly participated in the project report greater levels of political participation post-treatment? Argrawal, Chhatre and Gerber suggest one possibility – consistent with resource theory – is that they gained additional resources through their project experience and now find political participation less costly. They plan to explore alternative explanations, including reverse causality, in future analyses.

Feb 20, 2015 | Foreign Affairs, International, Profile

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Ugo Troiano.

This post is part of a researcher profile series that explores how Center for Political Studies (CPS) researchers came to their work. Today we profile Ugo Troiano, Faculty Associate in CPS and Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics.

Growing up in Taranto, Italy, Ugo Troiano became fascinated with debate over the local steel factory. He followed discussions of how dormant policies could influence economics. This opened Troiano to a bigger question: How can policies improve the life of the people?

Growing up in Taranto, Italy, Ugo Troiano became fascinated with debate over the local steel factory. He followed discussions of how dormant policies could influence economics. This opened Troiano to a bigger question: How can policies improve the life of the people?

Troiano already loved the social sciences and math. In economics, he found a fusion of the two and a toolbox to tackle this big question. He studied economics at Bocconi University. During his junior year, Troiano studied abroad at the University of Pennsylvania. This experience opened his eyes to the fruitful research environment of U.S. universities. After graduating from Bocconi, he enrolled in Harvard University’s Department of Economics to pursue a Ph.D.

For his dissertation, Troiano continued to explore the question of how policies can improve lives. In particular he looked at (1) how fiscal restrains can reduce government debt, (2) how a government program to combat tax evasion impacted vote choice, and (3) how maternity leave policies reflect gender equality.

Troiano continues to explore the central question of his research, studying how political incentives shape the implementation and consequences of public policies, using both traditional economic tools and tools from other social sciences, especially psychology, linguistics, sociology and political science. He joined the Department of Economics at the University of Michigan in 2013. He joined the Center for Political Studies, which he sees as reflecting the political science underpinnings of his work, in the fall of 2014.

Feb 11, 2015 | Elections, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Nahomi Ichino.

In many new democracies in developing countries, political parties are identified with particular ethnic groups, and voters tend to vote for the parties identified the same ethnicity as themselves – but not always.

Assistant Professor of Political Science and faculty associate of the Center for Political Studies (CPS) Nahomi Ichino addresses this issue in a recent article with Noah Nathan published in American Political Science Review.

Voters tend to believe that politicians will reward their co-ethnic supporters by building schools and health facilities and providing other services that benefit a limited local area. For voters who live among mostly people of their own ethnic group, it makes sense to vote for the party of their own group.

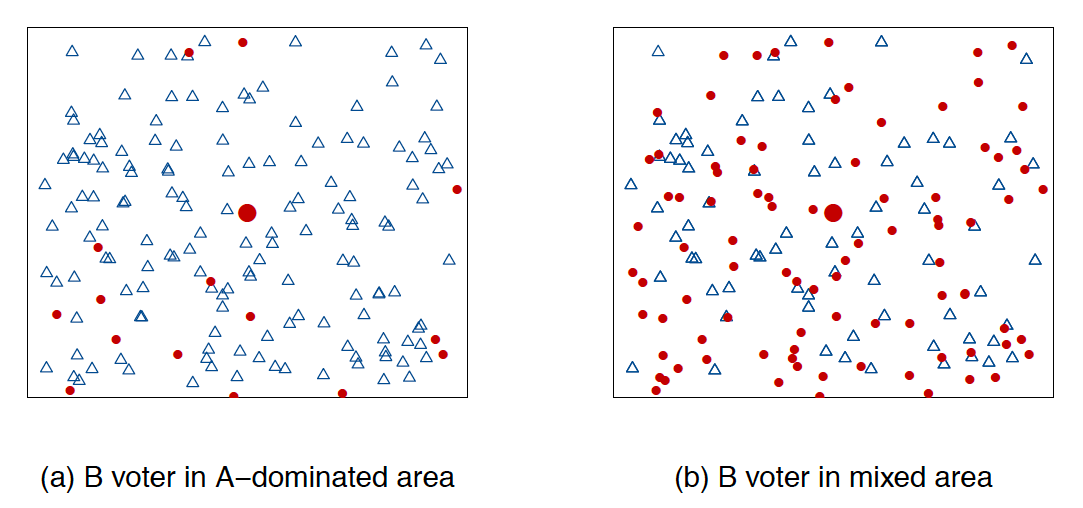

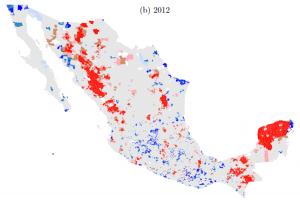

But voters sometimes find themselves living in an area dominated by another group or in a mixed area, and the calculation is more difficult. Take for example the first visualization (a) offered by the authors. A voter (circle) is surrounded by others of a different ethnicity (triangles). That voter might do better if a party of the other group (triangles) won the election and directed more benefits like schools to this area than if the party of her own group (circles) won the area and directed benefits to a different area with many of her own group (circles). If that same voter were in (b), where she is surrounded by more members of her own group (circles), then she becomes more likely to vote for the party of her own group than if she were in (a).

Voter Ethnicity Illustration

Ichino and Nathan tested these predictions Ghana. First, the authors mapped ethnic concentration and diversity with data from the 2000 Ghana Population and Housing Census. Then, they geocoded polling stations results to look at how elections results vary with local ethnic composition in rural areas.

Ichino and Nathan first focused on the 2008 presidential election results in Ghana’s Brong Ahafo, a region that is both rural and ethnically diverse and find support for their ideas. Polling stations in areas surrounded by more Akans had higher vote shares for the political party associated with the Akan. The authors also tested their hypothesis with survey results from the Afrobarometer. They similarly find that Ghanaians were more likely to intend to vote for a political party associated with an ethnic group when they were surrounded by more members of that group.

The authors believe their findings nuance the generally accepted idea that people in new democracies simply vote for candidates who share their ethnicity. Ichino and Nathan conclude that their study “demonstrates how local community and geographic contexts can modify the information conveyed by ethnicity and influence voter behavior.”

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).