Jun 24, 2014 | ANES, Elections, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Spencer Piston.

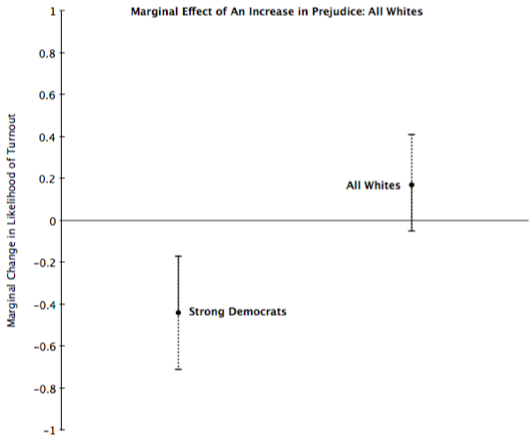

The 2008 election in the United States featured the first black major party presidential candidate in U.S. history – Barack Obama. Obama won in a historic election. But was his victory margin narrower than it could have been? In particular, did racial prejudice erode Obama’s vote share among those whites expected to vote for him: strong Democrats?

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Center for Political Studies (CPS) affiliate and Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan Spencer Piston explored this question with co-author Yanna Krupnikov (Northwestern University) in a recent article published in Political Behavior.

The researchers identify a gap in the field. Where previous work focuses on the connection between prejudice and vote choice, few studies have considered the relationship between prejudice and turnout on Election Day.

The researchers evaluate the relationship between racial prejudice, strength of party identification, and turnout. They are especially interested in a situation in which a white voter, high in racial prejudice, is faced with a black candidate from her party. How will the voter vote? In this scenario, racial prejudice is pitted against party identification.

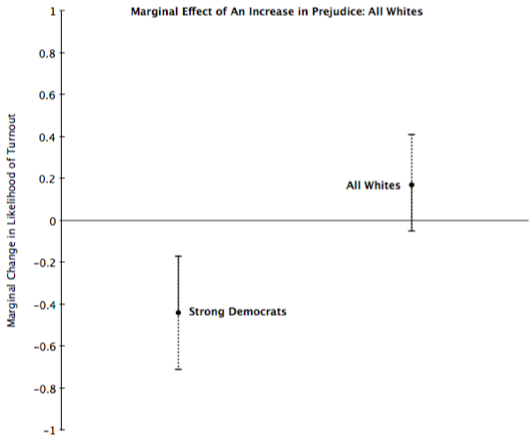

Examining 2008 data from the American National Election Studies and replicating their analyses with survey data from a wave of a 2007-2008 Associated Press-Yahoo! News-Stanford University study, the authors find that highly partisan and prejudiced voters often address the tension embodied in a black candidate from their party by not turning out to vote. Interestingly, the authors also test if this group would instead vote for the white Republican presidential candidate John McCain. They would not. This is because they cannot compromise on race or partisanship. Unable to compromise, they instead choose not to vote.

These findings have significant implications for American elections. The authors conclude, “Racial prejudice undermines black candidates’ efforts to mobilize strong partisans.”

Spencer Piston will join Syracuse University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Political Science.

Jun 9, 2014 | ANES, ANES 65th Anniversary, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Deborah Schildkraut.

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).

In this post, we consider the impact of ANES on teaching.

First, we hear from Tufts University Professor of Political Science Deborah Schildkraut, who shares her experience using ANES in the classroom. From Schildkraut:

ANES impacts my teaching in two key ways. First, I use raw ANES data in my lectures.Second, the research I rely on as I teach and that I think is really meaningful for my students includes:

All take advantage of the time series to help demonstrate both the importance of fundamentals and the role of particular events in shaping attitudes, behaviors, and election outcomes. And all are written at a level that combines sophisticated methods but approachability such that undergrads can engage with them.

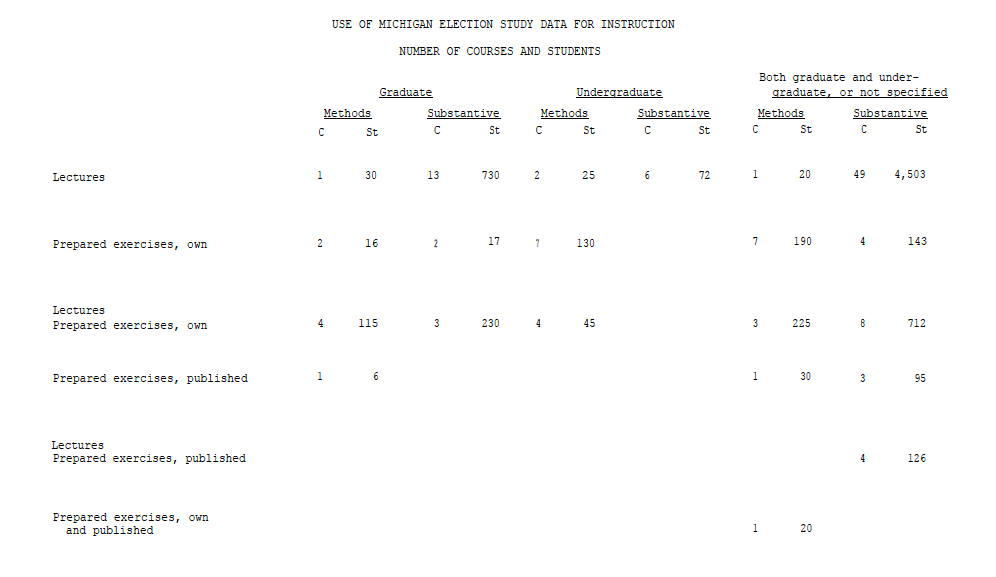

Second, in a 1977 grant proposal to the American National Science Foundation (NSF), ANES founder Warren Miller outlined the current and potential use of ANES in teaching. This excerpt from the proposal encapsulates his analysis and vision:

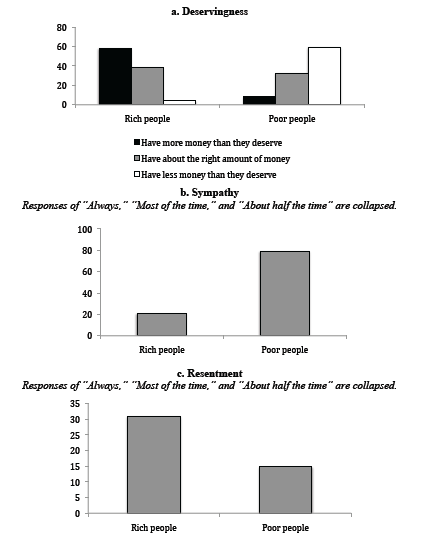

The election data are even more widely used in activities related to teaching. Reports from the same roster of political scientists who were questioned about research use of the data indicate that the data were being used for teaching purposes in some 480 courses taken by more than 18,000 students… Given the reasonably short history of the systematic use of quantitative data by political science students in meeting course requirements, we were surprised to discover that three-quarters of the students using the data were actually undergraduates.

The hand typed table below from the 1977 proposal details the use of ANES (then called the Michigan Election Study) in the university classroom.

Miller then concluded, “The election studies promise to play an increasingly significant role in undergraduate teaching.” Professor Deborah Schildkraut’s use of ANES nearly forty years after the 1977 proposal demonstrates the continued reach of ANES in the classroom.

May 29, 2014 | ANES, Current Events, Innovative Methodology, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Spencer Piston.

The gap between the rich and poor in the United States is growing. Occupy Wall Street, fast food worker strikes, and other manifestations of this gap make headlines often. And just a few weeks ago, President Obama visited the University of Michigan to champion raising the minimum wage.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

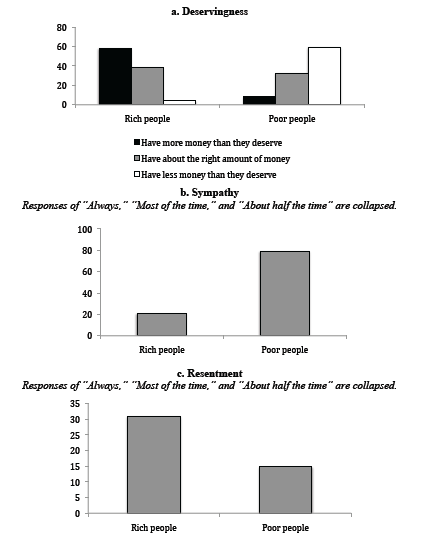

Despite these movements, previous academic work suggests Americans look down on the poor. The news media perpetuate this message. The Economist claims, “Americans want to join the rich, not soak them,” while The New York Times published an article with the headline, “New Resentment of the Poor.”

But what if previous research and the mainstream media are wrong? What if anti-rich movements better capture the American ethos? Center for Political Studies (CPS) affiliate and Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan Spencer Piston investigated this issue.

Piston addresses this question with an innovative approach. Previous scholarship measures attitudes with questions about “economic inequality” and “government-led redistribution.” But these are terms that survey respondents rarely use without prompting, and Piston finds reason to believe that many Americans don’t understand what these terms mean.

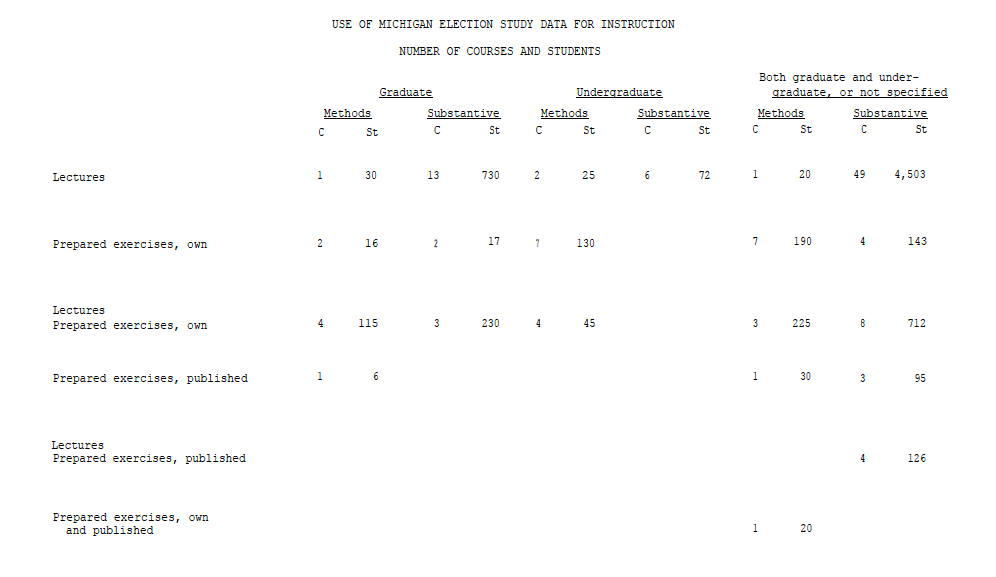

Piston therefore begins with a straightforward but rarely-used survey technique: he asks people how they feel about the poor and the rich. Piston examines answers to these questions using an original survey, and supplemented with American National Election Studies (ANES) data. The graphs below depict feelings of (a) deservingness, (b) sympathy, and (c) resentment toward and the rich and the poor. As we can see, people tend to see the rich as deserving less and the poor deserving more. They also see the poor as more sympathetic than the rich, and the rich as objects of more resentment than the poor.

Feelings toward the Rich and Poor

a. Do the (rich, poor) have more or less money than they deserve?

b. How often have you felt sympathy for (rich, poor) people?

c. How often have you felt resentment toward (rich, poor) people?

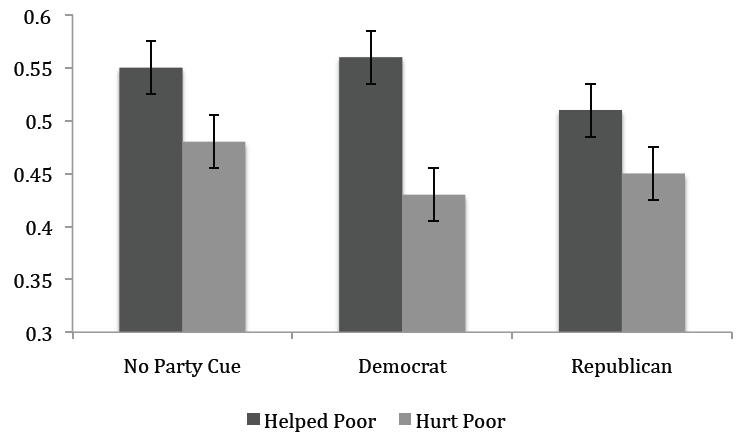

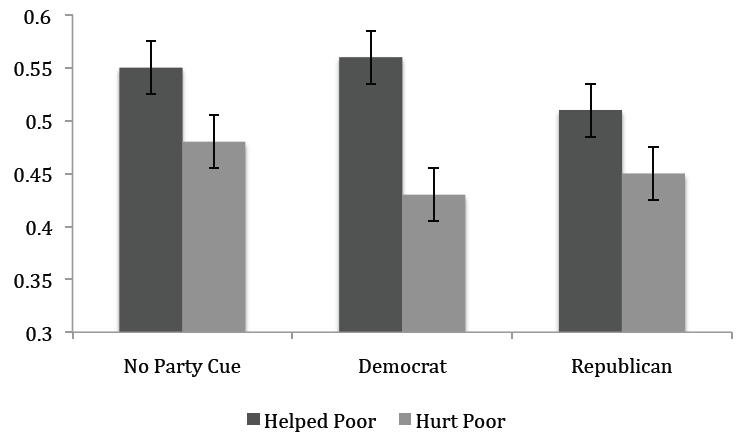

What effect might these Robin Hood attitudes have on elections? Piston tested this with several survey experiments. He finds that that a candidate who supports the poor garners more support among voters than an otherwise identical candidate who hurts the poor, regardless of the candidate’s party.

Effects of Candidate’s Record on Mean Support for the Candidate

Taken together, these results suggest that previous research has overestimated public support for economic inequality and public opposition to downward redistribution. When survey questions are worded using terms that survey respondents more commonly use, it appears that many Americans want government to give more to the poor – and to take from the rich.

Spencer Piston will join Syracuse University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Political Science.

May 22, 2014 | ANES, Elections, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ioannis Andreadis.

Voting Advice Applications (VAAs) are web platforms that help voters determine the candidate or the political party that best matches their own political ideology. Visitors answer a series of questions to gauge their political positions. The VAA platform then estimates the similarity or dissimilarity of these positions to those of candidates or parties.

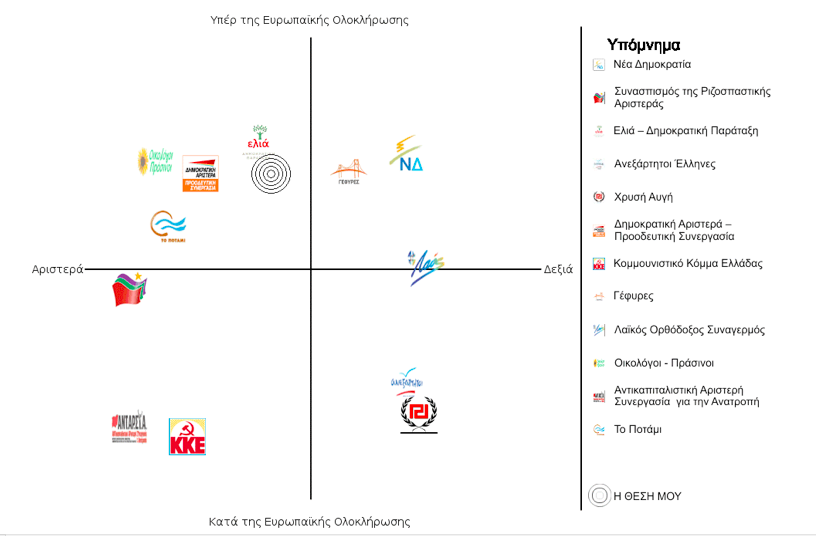

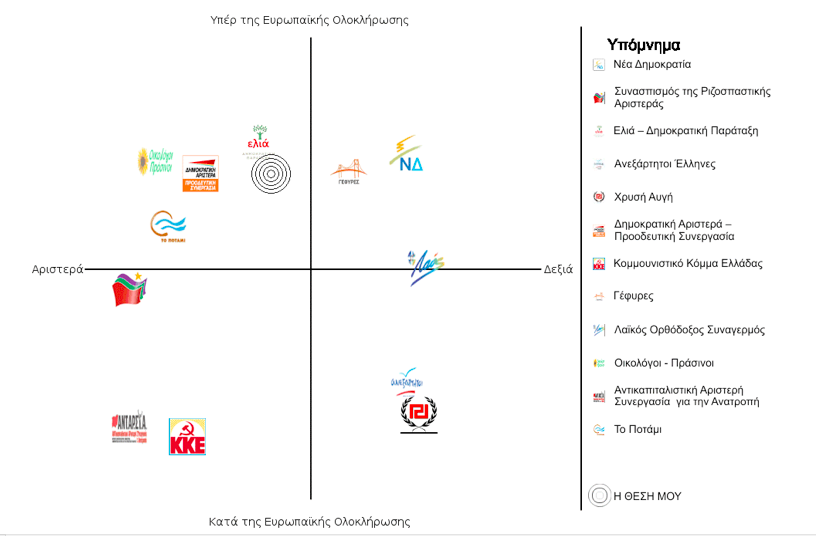

There are various ways to present these estimates. One option is to display a list of the candidates or parties along with a number indicating the similarity or dissimilarity of each. Another option is a graph like the one below from Greece, where issues from the election are represented on each axis, and users can visualize their ideological position relative to that of the parties.

-

Example of diagram from the Greek VAA www.votematch.gr from the elections for the European Parliament. Left/Right is represented by the horizontal axis and Pro-Europeanism/Euroscepticism is represented by the vertical axis. The political party logos indicate their ideological position and the center of the concentric circles indicates the position of the user.

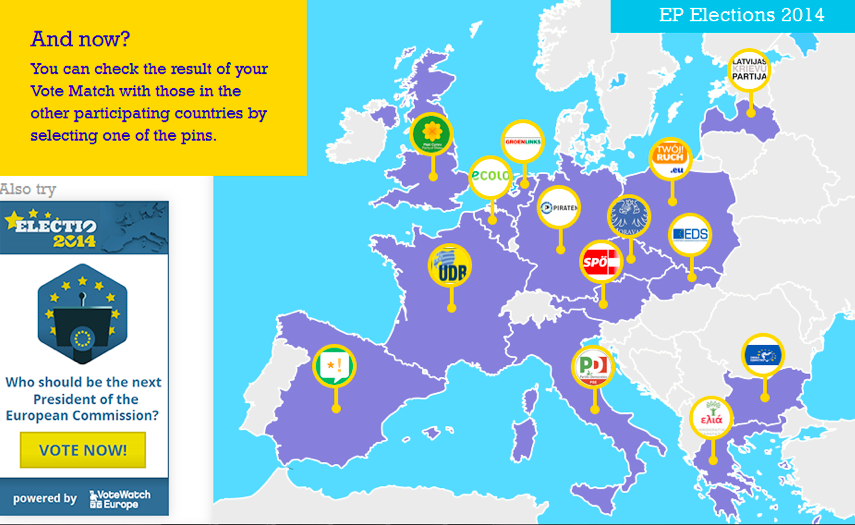

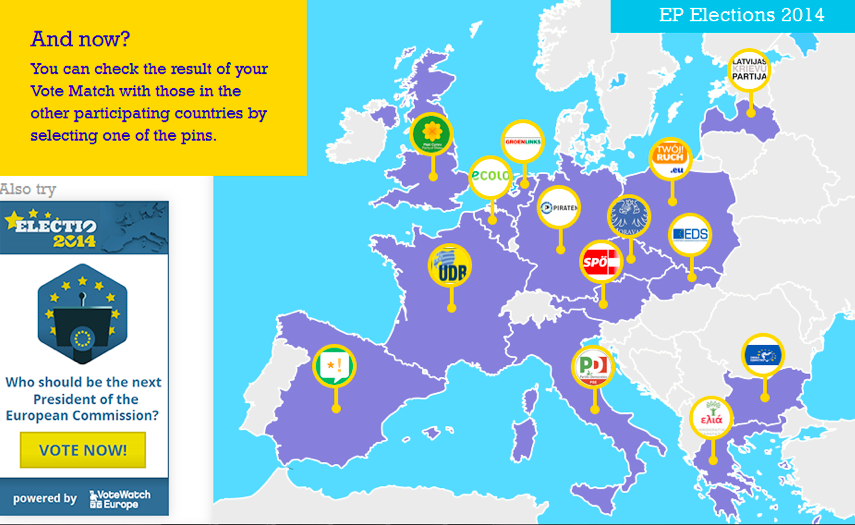

Another example of VAAs in action is Vote Match Europe, an international network of VAAs for the 2014 European Parliament elections across fourteen EU countries. The Vote Match Europe website allows users to see the parties closest to them across all of the countries in the network, and to learn more about the parties and their policies. A goal of the Vote Match Europe website is to promote European citizenship and better inform citizens about the elections for the European Parliament at large.

Ioannis Andreadis is Assistant Professor of Quantitative Methods in the Department of Political Sciences at Aristotle University Thessaloniki. This semester, he is a scholar in residence at the Center for Political Studies (CPS), seeking to learn more about the American National Elections Studies (ANES) and the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) under a grant from the Fulbright Program.

In his capacity as a researcher, Andreadis has studied and written about VAAs, and he also both designs and studies VAAs. In particular, he created and oversees the Voting Advice Application HelpMeVote. HelpMeVote was used by more than 480,000 voters during the May 2012 Greek Parliamentary Elections. The application was also used in Iceland and Albania, and is currently being used for the 2014 European Parliament election.

In a recent paper, Andreadis tackles the question of utility of VAAs. He suggest that VAAs must be built to high academic standards, and realize the following benefits:

- VAAs help voters should become more knowledgeable about party positions, allowing the voters to make better choices.

- VAAs help political parties not covered in traditional media to connect with voters who agree with their values.

- VAAs generate data that researchers can use to better understand voting behavior.

VAAs are growing in popularity in places with multi-party systems and high Internet availability – for example, in Western Europe.

In electoral systems with only two parties, VAAs may be less useful given the limited choice set. If a VAA had been used for the 2009 Greek elections or earlier – when two major Greek political parties dominated national politics – it probably would not have been as popularly used. But in the 2012 elections, the Greek parliament featured seven parties, making way for a new VAA market.

With this in mind, adaptation to America’s two party system poses challenges. VAAs could be used in American primaries, where many candidates from the same party compete against each other, but only if candidates running in the same primary have very different positions on enough issues.

May 8, 2014 | ANES, Current Events, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ashley Jardina.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

This month, Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy made headlines. What started as a battle against the U.S. Federal Government for his cattle and land turned into daily press conferences. As part of the Sovereign Movement, Bundy used the attention to propagate an anti-government agenda and racist ideas. Across the country at Princeton University, freshman Tal Fortgang also made headlines with his essay, “Checking my Privilege.” His championing of white privilege garnered backlash in the press. What do Bundy and Fortgang have in common? Both demonstrate reactions to a perceived status threat to whites.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) affiliate and Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan Ashley Jardina studies white identification. In particular, she argues that threats to dominant status make racial identity salient. Does this in turn influence support for political policies that could eliminate such status threats?

To answer this question, Jardina analyzed data from the American National Election Studies (ANES). Especially relevant is a measure of racial identity importance available for the first time in the 2012 ANES. This measure let Jardina gauge the extent to which white Americans feel that being white is important to their identity. She looks at whether this white identity relates attitudes toward policies (e.g., immigration) and candidates (e.g., Barack Obama) that exacerbate threats to white dominance. Immigration especially threatens whites’ dominance, because it drives demographic changes whereby whites are being displaced as the majority racial group in the nation. Likewise, as the country’s first African American president, Obama also represents a status threat.

Previous work has argued that out-group attitudes, either toward Hispanics or blacks, primarily drive whites’ attitudes toward immigration policy and support for Obama. But Jardina constructs models to explicitly test the relationship between in-group / out-group feelings. She finds in-group identity to be a more powerful and consistent predictor of restrictive immigration policies than out-group attitudes, including evaluations of Hispanics. Furthermore, whites who identified with their racial group were significantly less likely to vote for Obama, even after controlling for racial prejudice or resentment. Her results are replicated using two other datasets. Jardina concludes, “These results lend support for the notion that, in some important cases, a desire to protect the in-group, rather than dislike for the out-group, primarily drives opinion.”

Ashley Jardina will join Duke University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Political Science.

Apr 29, 2014 | ANES, ANES 65th Anniversary

Post Developed by Lynn Vavreck and Katie Brown.

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science. Do you have ideas for additional posts? Please contact us by email ([email protected]) or Twitter (@umisrcps).

In this post, we consider the impact of ANES on a seminal work in the field, Lynn Vavreck’s The Message Matters.

Lynn Vavreck is a Professor of Political Science and Communication Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Her book, The Message Matters: The Economy and Presidential Campaigns, considers the role of the economy and candidate’s reactions to the economy in determining election outcomes.

Vavreck supports this idea by analyzing six decades of elections. She considers why, when, and how campaign messages matter. The election data came from the American National Election Studies (ANES), underscoring the utility of time series data. Vavreck writes of her experience writing the book…

Without the ANES, I never could have written The Message Matters, which essentially treated each presidential candidate over the last 17 elections as an observation. With only 34 cases to work with, I leveraged the power of the tens of thousands of cases the ANES offered over that same time period to test implications of my work among voters. Because of these data, I was able to show that the things presidential candidates talk about in their campaigns affect voters in predictable and important ways. Quite apart from being irrelevant, presidential campaigns play an important role in election outcomes.

Using ANES data, Vavreck concludes that the economy is the single most important feature of elections since 1950, affirming prior research in the field. The Message Matters goes one step farther, demonstrating that it is against the economic backdrop that candidates must cast themselves. The messages they promote matter. In particular, how they speak about the economy matters. And how they speak about other issues matters, particularly as it affects room for discourse about the economy.

The Message Matters garnered critical praise upon its release. Paul M. Sniderman, Professor of Public Policy and Political Science at Stanford University, writes, “I have not read a book of comparable elegance of argument and mastery of analysis in years. It is outstanding on three dimensions. In its combination of analytical depth and economy, it is a model for research on election campaigns. In its fusion of theory and empirics, it is a model for research in political science. In its principled, persistent, ingenious efforts to turn up evidence against its own hypotheses, it is a model for the social sciences.” Larry M. Bartels, Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt, raves, “Vavreck’s creative theorizing and informative historical analysis will change the way political scientists think about presidential campaigns. While giving campaign strategists their overdue due, she also sheds invaluable light on how political contexts shape their strategies and their odds of success.” Campaign consultant and pollster Stanley Greenberg declared the book “a must read” for future presidential candidates.

In sum, Vavreck’s important book was made possible in part by the time series data provided by ANES.