Mar 5, 2014 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Muzammil Hussain

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In recent weeks, massive protests have swept through Venezuela and Ukraine. Instagram and Twitter have been featured as playing a key role in the latter. Digital activism is increasingly attributes to helping spark rapid waves of mobilization across several recent international cases.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate and assistant professor of communication Muzammil Hussain studies the role of technology in protest. With Philip N. Howard of the University of Washington, Hussain published an article weighing the roles of Internet infrastructure and mobile telephony in the Arab Spring mobilizations.

Though in a different area of the world, understanding the role of communication systems, the political uses of digital media, and the politicization of internet infrastructure in the Arab Spring can help shed light on the current wave of democratization. Hussain argues that information technologies do not cause political change, but they have become a consistent tool and space to afford and act out political contentions.

To understand the relative success of the Arab Spring across different countries in the Middle East and North Africa, the authors look at a variety of contextual factors, including income, wealth distribution, unemployment, demographics, digital connectivity, censorship, and economic dependence on fuel. In the article, they examine the impact of these factors on regime fragility and social movement success. Interestingly, they argue that the inciting incidents in each country were digitally mediated. The describe how digital communication sets off a six-stage process of political mobilization experienced in both successful and failed attempts for regime change.

The authors conclude that “information infrastructure – especially mobile phone use – consistently appears as one of the key ingredients in parsimonious models for the conjoined combinations of causes behind regime fragility and social movement success.” That is, digital communication networks, especially mobile phones, drive political upheaval. In addition to offering insight into the Arab Spring experiences, this may also help explain the recent successful ousting of Ukraine’s president.

Feb 3, 2014 | ANES, Conflict, Current Events, National, Social Policy

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Darrell Donakowski.

Source: Thinkstock

On September 16, 2013, a former reservist killed 12 people in a Washington, D.C. Navy Yard. This latest high profile mass American shooting prompted President Obama to urge another push for stronger gun control. Obama first marked the issue as a national priority after a gunman shot and killed 20 first graders and six educators in a Newtown, Connecticut elementary school in December 2013. Obama promised to do everything in his power to prevent another such tragedy. In a Newtown vigil, and referencing the Aurora, Colorado movie theater shooting of the previous summer that killed 12 and injured 70, Obama declared enough.

Obama’s post-Newtown proposals included tougher background checks to purchase arms and the ban of military-style assault weapons used in several high profile mass shooting. But the package stalled in Congress. After the Navy Yard shooting, Obama urged the electorate not to accept mass shootings as a new normal, instead to demand common sense gun laws.

How do the American people feel about gun control?

For 65 years, the American National Election Studies (ANES) have interviewed a representative sample of voting age Americans on a variety of topics, including but not limited to voting and turnout, public policy support, societal values, and demographics. As ANES describes, the resulting data “inform the nation about itself.” Data from the 2012 survey were released at the end of June 2013.

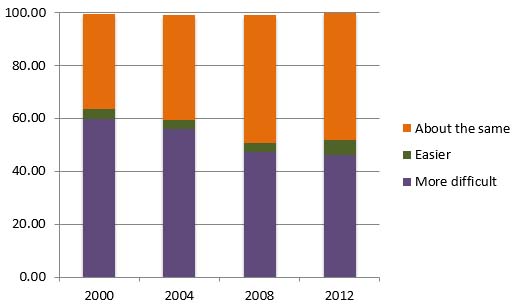

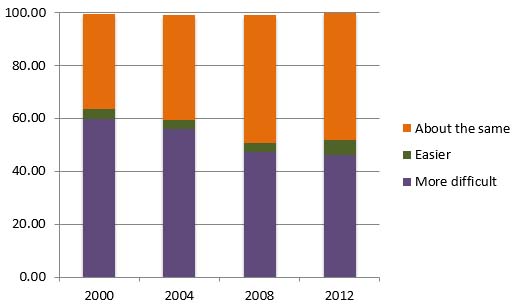

One question in particular from the ANES sheds light on national attitudes toward gun control. The question was asked in 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012, allowing us to trace responses over time. The graph below displays these trends (leaving out the small fractions who did not know or refused to answer).

Do you think the federal government should make it more difficult for people to buy a gun than it is now, make it easier for people to buy a gun, or keep these rules about the same as they are now?

As we can see, the proportion of the public supporting tougher regulation is shrinking over the time period, while satisfaction with current regulations increased. Yet, support for tougher gun laws is the most popular choice in all included years. It is important to note that these data were collected before Aurora, Newtown, and the Navy Yard shootings. The 2016 ANES study will no doubt add more insight into this contentious, important issue.

Oct 28, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Mark Tessler.

Egypt attracted international attention as a key participant in the Arab Spring. Along with Tunisia, it was among the first countries to witness the fall of a decades-long authoritarian regime. In early 2011, protestors demanded that then Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak step down. In February 2011, Mubarak relented, turning over power to the military.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In November of 2011, the country held parliamentary elections and these were won by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party. In June of 2012, the Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi was elected president of Egypt. Over the next year and a half, Morsi pushed remaining officials from Mubarak’s reign out of government, all the while consolidating his power.

With the economic situation deteriorating, and with conflicting claims about who was responsible, anti-Morsi protests spread throughout Egypt in summer 2013. Then, on July 3, 2013, in response to the growing unrest, the military removed Morsi from office. Violent clashes between the military and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood followed and have continued sporadically since that time.

A key question raised by these events, and by post-Arab Spring developments in a number of other Arab countries, concerns the role to be played by Islam in government and political affairs. As expressed by Egypt’s Grand Mufti in April 2011, following the ouster of Mubarak, “Egypt’s revolution has swept away decades of authoritarian rule but it has also highlighted an issue that Egyptians will grapple with as they consolidate their democracy: the role of religion in political life.”

Center for Political Studies (CPS) Researcher and Samuel J. Eldersveld Collegiate Professor of Political Science Mark Tessler is making major strides to understand what ordinary citizens in Egypt and other Arab countries think about the complicated and contested relationship between religion and politics in the Middle East. Among the data on which Tessler is drawing is the multi-country Arab Barometer survey project, which Tessler co-directs. Arab Barometer surveys in Egypt in 2011 and 2013 offer insights about how recent events have influenced the way the Egyptian public thinks about Islam’s political role.

One finding from these surveys is that most Egyptians believe democracy and Islam to be fully compatible, and this view did not change between 2011 and 2013. On the other hand, while most Egyptians have confidence in Islam itself, there has been a dramatic decrease over this period in the proportion that believes that the country is better off when religious people hold public office. Some Egyptians describe this as wanting Islam but not Islamists.

These Arab Barometer surveys are part of a larger dataset pertaining to Islam and governance that Tessler has constructed with support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The dataset pulls together information from 44 nationally representative surveys conducted in 15 countries in the Middle East and North Africa and includes not only respondent political and social attitudes but also major characteristics of the country of which the respondent is a citizen.

Tessler’s analysis of these data will be published in a forthcoming book, Islam and the Search for a Political Formula: How Ordinary Citizens in the Muslim Middle East Think about Islam’s Place in Political Life. The book will offer a deeper understanding of the desired role of Islam in politics across the Middle East, a religion and region often misrepresented in American media, politics, and minds. In addition, the database will be placed in the public domain for use by other scholars who study the relationship between religion and politics.

Oct 14, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with James Morrow.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

The horror in Syria has gripped international attention, especially in recent weeks with the release of images of those killed by chemical weapons. But why would Bashar al-Assad, the President of Syria, use chemical weapons when he is winning the civil war against insurgents?

Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor and A.F.K. Organski Collegiate Professor of World Politics James Morrow recently spoke to this issue on MSNBC’s The Last Word. Assad’s target was a rebel controlled neighborhood in Damascus, the capital of Syria. A large chemical attack would scare other civilians, inducing them to flee for safety. After they left, Assad could move his forces into one the few remaining rebel areas. Morrow also highlights the timing of Assad’s chemical strike: it occurred after the rebels began to lose ground across Syria. Assad used chemical weapons precisely because he is winning.

Morrow’s comments on MSNBC are grounded in his research. In a forthcoming book, Order Within Anarchy, Morrow models violations of the laws of war, like the use of chemical weapons. Violations typically come early in war. When they come later – as in Syria – violations tend to be perpetrated by the winning side. The violation itself increases the perpetrator’s chance to win the war. Thus, Assad’s deployment of chemical weapons could be seen as a coup de grâce.

Yet, Assad also faced a strong global backlash. Obama declared a red line crossed and seemed poised to order counter-attacks on Assad. Such a strike could undo any gain from the chemical weapons. But, Russia – who, with China, blocked approval to counter-attack Syria in the United Nations – proposed an alternative solution: order Assad to surrender his chemical weapons for destruction by international monitors. Obama and Assad agreed to this approach. Last week, Assad received praise for his steps to chemically disarm. And also last week the Nobel Prize committee awarded the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons with the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to disarm Syria. But the gains of his use of chemical weapons remain.

Aug 7, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Christian Davenport

Photo credit: Thinkstock

On August 5, 2013, a Turkish court convicted 275 people, including ex-military officers, of plotting to overthrow Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Though the court case took five years, the verdict comes at a tenuous moment in Turkish politics, deepening the divide between Ergodan and critics.

This summer, protests erupted across Turkey. Initially a movement against the planned development of Taksim Gezi Park, a rare patch of green in the city of 13.5 million, the uproar spread as general government dissent. A small fraction of the protestors resorted to violence. The government cracked down with force in response. Erdogan initially presented a mixed message, alternating between ultimatums, violence, and agreeing to meet with protestors. By the end of June, his message and tactics showed more force. More than 5,000 were injured and 4 killed. Doctors tending to the wounded were arrested, a fact verified by Erdogan. The government also worked to block social media, blamed for spreading the word. And Ergodan lashed out against international media, claiming false representation.

The violence is noteworthy in a country with an emerging democracy with dreams of ascension into the European Union. But is the violence really a surprise?

Research on violent dissent by Center for Political Studies researcher Christian Davenport sheds light on the current situation in Turkey, through his work on the power of democracy to ease repression. A central thesis of the work asserts the calming power decreases in the face of violent dissent. Using a cumulative index created by Polity, Davenport published an article with David Armstrong. The authors find that lower levels of democracy, unlike higher levels of democracy, have no calming influence on violent repression.

A graph from Polity shows the trend over time, illustrating that Turkey is not just a weak democracy, but emerging in many senses. Davenport’s work helps us understand that the violent reaction in response to anti-government protests is not surprising given Turkey’s relatively weak democracy. Turkey’s democracy is weak enough that it cannot pacify repression of this sort.

The EU passed a resolution in response to the violent repression. Erdogan fired back that the EU should, “know [its] place!” The repression was not quelled by Turkey’s weak democracy, nor it seems the EU, both of which are challenged by the violence.

Interestingly, the protests in Turkey are credited with inspiring anti-government protests in Brazil. And while initial protests in Brazil were met with tear gas and rubber bullets, the number of injuries rests near 100. Prime Minister Dilma Rousseff even supported the right to protest, while expressing interest in listening: “These voices need to be heard, my government is listening to these voices for change.” Yet the protests continue and are forecasted to continue up to the 2014 World Cup, hosted in Brazil and a source of dissent.

Jul 2, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Christian Davenport (@engagedscholar).

On June 13, 2013, news of the political terror in Syria reached a breaking point. Under President Bashar al-Assad, 92,000 Syrians have been killed. Recent evidence suggests the use of chemical warfare, including sarin gas. Though the civil war has festered for years now, the global community is only beginning to respond. In the wake of this new information, the White House ordered aid to select rebels. On June 18, 2013, the G8 summit supported urgent peace talks in Geneva with Syria. Regardless of how the world’s super powers intervene, the violence is staggering. How can we understand such repressive strategies?

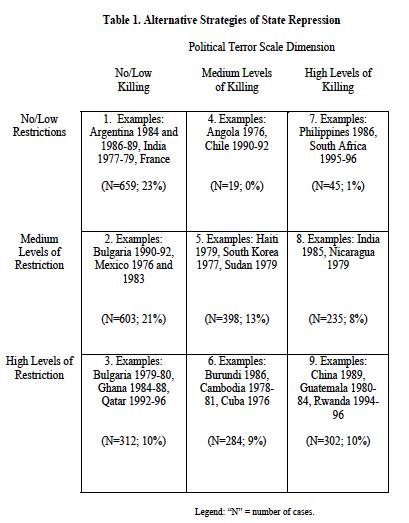

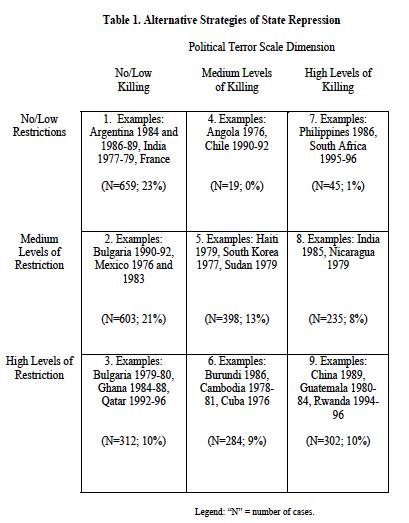

Center for Political Studies researcher Christian Davenport’s work on violent dissent offers insight into Syria’s present state. Davenport’s research uses the Political Terror Scale to operationalize physical torture and elimination of citizens. Both Amnesty International and the U.S. State Department rate Syria at the highest end of this scale, with a 5, defined as: “terror has expanded to the whole population. The leaders of these societies place no limits on the means or thoroughness with which they pursue personal or ideological goals.”

Davenport creates a conceptualization that goes one step further. The resulting grid plots level of restriction against level of killing. Syria rates high on both accounts, making the current situation comparable to other notorious times and places: China in 1989, Guatemala in 1980, and Rwanda from 1994-1996.

Davenport creates a conceptualization that goes one step further. The resulting grid plots level of restriction against level of killing. Syria rates high on both accounts, making the current situation comparable to other notorious times and places: China in 1989, Guatemala in 1980, and Rwanda from 1994-1996.

Davenport’s research emphasizes the dire nature of the situation in Syria. We have little insight into how such activities are ended (something that is sorely needed), but one thing that we do know is that within such situations political leaders are not as sensitive to external policies that under normal circumstances would seem quite costly.