Dec 11, 2014 | ANES, ANES 65th Anniversary, National

Post developed by Katie Brown.

This post is part of a series celebrating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science.

University of Michigan political scientists Angus Campbell, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes published The American Voter in 1960. The American Voter takes root in a time of changing notions about individuals and decision-making. In the 1940s, Paul Lazarsfeld and the Columbia school placed a new emphasis on demographic factors in responses to media and support for President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In The American Voter, Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes became part of this behavioral revolution as they considered audience traits in the context of politics. The main argument of the book holds that most American voters cast their ballots on the basis of party identification. Specifically, voter decisions pass through a funnel. At the opening of the funnel is party identification. With this lens, voters process issue agenda. They then narrow down to evaluate candidate traits. Finally, at the small end of the funnel is vote choice. This understanding of voters encompasses the “Michigan Model.”

In The American Voter, Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes became part of this behavioral revolution as they considered audience traits in the context of politics. The main argument of the book holds that most American voters cast their ballots on the basis of party identification. Specifically, voter decisions pass through a funnel. At the opening of the funnel is party identification. With this lens, voters process issue agenda. They then narrow down to evaluate candidate traits. Finally, at the small end of the funnel is vote choice. This understanding of voters encompasses the “Michigan Model.”

In time, the Michigan Model was revised. The original Michigan Model held party identification as king. This thesis maps onto the strong post-World War II Democratic party, strengthened by Roosevelt. In the next few decades, party identification weakened. More recently, party identification reemerged stronger than ever due to a variety of factors, including changing campaign strategy and polarization.

So while these new generations of scholars find different balances between party identification and other factors influencing vote choice, The American Voter provided a bar against which this change could be measured.

The American Voter also enabled the tools of measurement with ANES. The American Voter utilized early waves of what would become the American National Election Studies (ANES), which Miller himself facilitated. The ANES developed into a multi-wave, decade-spanning project offering continuous data on the American electorate since 1948.

Cited over 6,500 times to date, the book remains a seminal text in political science.

Dec 4, 2014 | ANES, Elections, Innovative Methodology, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Shanto Iyengar.

The inaugural Michigan Political Communication Workshop welcomed renowned political science and communication scholar Shanto Iyengar from Stanford University. Iyengar presented a talk entitled “Fear and Loathing across Party Lines.”

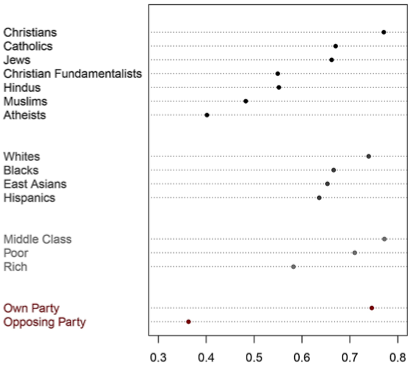

Iyengar began by considering the current polarized state of American politics. Both parties moving toward ideological poles has resulted in policy gridlock (see: government shutdown, debt ceiling negotiations). But does this polarization extend to the public in general? To answer this question, Iyengar measured individual resentment with both explicit and implicit measures.

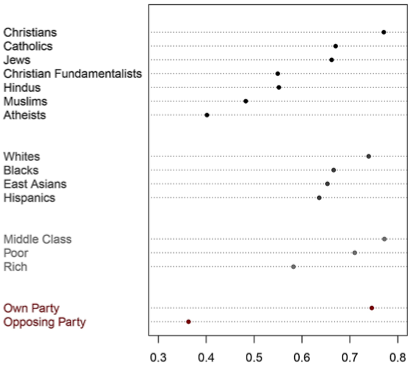

2008 ANES: Party vs Other Divisions

For an explicit measure, Iyengar turned to survey evidence. The American National Election Studies (ANES) indeed illustrates a significant decline in ratings of the other party based on feeling thermometer questions. Likewise, social distance between parties has increased over time, as measured by stereotypes of party supporters and marriage across party lines. In fact, this out-group animosity marks a deeper divide than other considerations, even race (see graph below).

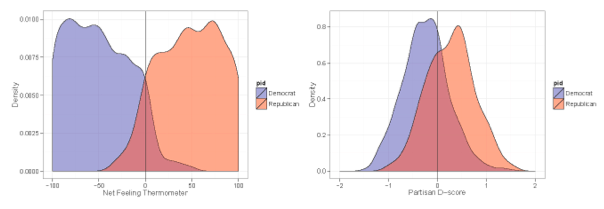

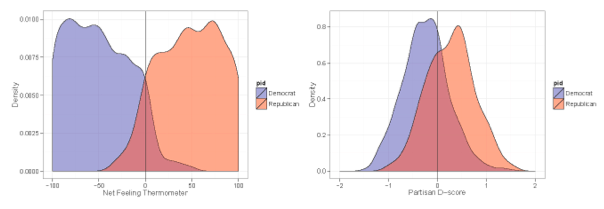

But these surveys gauge animosity at the conscious level. Iyengar also believes mental operations concerning out-party evaluations occur outside of conscious awareness. So, along with Sean J. Westwood, Iyengar pioneered implicit measures of out-party animosity. Specifically, Iyengar and Westwood adapted the Implicit Association Test— originally used to capture racism – to political parties. Interestingly, the IAT also captured this animosity, although the polarization was more pronounced with the explicit survey measures. The chart on the left shows the starker divide between Democrats and Republicans using the feeling thermometer; the chart on the right shows the difference with the IAT.

Comparing Implicit with Explicit Affect

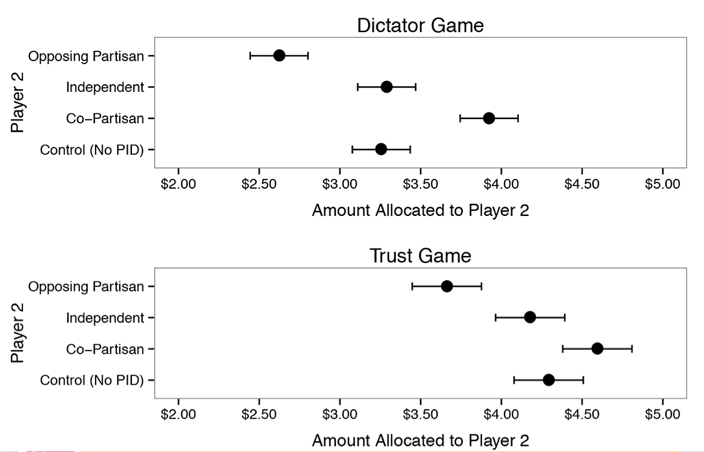

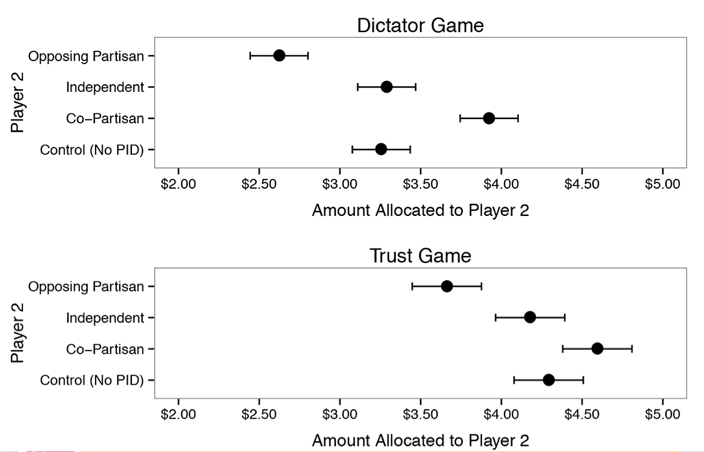

Iyengar also adapted classic economic games to test implicit out-party animosity. Both games allow the participant to share a proportion of money provided by the researchers. Interestingly, participants gave less to out-party opponents. Iyengar cites this as evidence of implicit out-party bias.

Economic Game Results by Party

Together, these results suggest marked party polarization. The hostility is so strong that politicians running on a bipartisan platform are likely to be out of step with public opinion.

Nov 25, 2014 | ANES, ANES 65th Anniversary

Post developed by John H. Aldrich (Duke University).

This post is part of a series celebr ating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science.

ating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science.

My contact with the ANES began in 1966, or maybe it was in 1967, in John Kessel’s class at Allegheny College, when we read that relatively new book, The American Voter. It was presented to us then as revolutionary and that assessment stands today. Since then, it has become my good fortune to be able to be involved in the ANES, on which that book was based, in a wide variety of ways. Let me mention two dimensions of the ANES, the CSES and the future.

The Comparative Studies of Electoral Systems (CSES), led into being by Steve Rosenstone from the ANES among others, is the extension of the aspirations of the ANES into a truly comparative context. That set of aspirations was to demand the highest quality research design and data collection to enable the strongest inferences possible about how elections work. CSES is primarily the comparative study of differing democratic institutions and cultures, and the idea is to have as close to “gold standard” data collected on exactly the same topics in as many electoral democracies as possible, so we can learn just what is special to particular nations or electoral systems and what is general. The notion, that is, is to make possible the strongest science of democracy we can. We are now entering the fifth round of such studies, and the advances are becoming quite remarkable (see www.cses.org for what is nearly 20 years of research). The point is that not only was the ANES the original model, an important source of leadership, and indeed, was the justification for NSF support for the project, but all that continues to this day.

The ANES (and indeed the CSES) is entering a critical period. There are two kinds of threats, and hence two kinds of opportunities. One threat is external. The cost of the maintaining the gold standard is very high, possibly unsustainably so, and funding in the U.S., as in many nations, is under threat. In the U.S., it is under political threat, as Congress seriously considers limiting the scope of the science it will support through the NSF. The internal threat is, of course, related to cost, but it is also that maintaining the gold standard of excellence in design faces new and ever stronger challenges. While the ANES has over time maintained a position at the head of the class in terms of response rates, its current response rates, like everyone else’s, are much lower than desired and also lower than they were not so long ago. And new technologies present new challenges as to how best to meet standards of excellence in research design and survey implementation. The need for both new science and its engineering counterparts in the face of declining interest in participating in surveys and other challenges is acute – but it is also something that the scientific community surrounding and supporting the ANES ought to be especially attuned to and especially good at creating. So, this is a challenge to the community to step up, as Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes and as Kish did 65 years ago.

Jul 23, 2014 | ANES, Elections, National

Post developed by Vincent Hutchings, Hakeem Jefferson, and Katie Brown.

The following post elaborates on a presentation titled “Out of Options? Blacks and Support for the Democratic Party” that was delivered at the 2014 World Congress of the International Political Science Association (IPSA).

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In 2012, Barack Obama received 93% of the African American vote but just 39% of the White vote. This 55% disparity is bigger than vote gaps by education level (4%), gender (10%), age (16%), income (16%), and religion (28%). And this wasn’t about just the 2012 or 2008 elections, notable for the first appearance of a major ticket African American candidate, Barack Obama. Democratic candidates typically receive 85-95% of the Black vote in the United States. Why the near unanimity among Black voters?

Vincent Hutchings, Professor of Political Science and Research Professor in the Center for Political Studies (CPS), and Hakeem Jefferson, Ph.D. candidate in the department of Political Science and CPS affiliate, set out to answer this question.

Hutchings and Jefferson especially sought to shed light on the “Black Utility Heuristic.” First proposed by Michael Dawson, the Black Utility Heuristic holds that Blacks tend to assess what is in the best interests of their racial group as a proxy for judging what are the best political decisions for them individually. So, given the widespread perception that the Democratic Party is best for African Americans, many Blacks support this party even if – in the case of the middle-class and social conservatives – it might not be in their individual interests to do so. But despite the reliance on this theory by numerous scholars, there exists little empirical support that it can account for Blacks’ lopsided support for the Democratic Party.

Using American National Election Studies (ANES) data, Hutchings and Jefferson tested the Black Utility Heuristic against other potential explanations for the near-unanimous support among Blacks for the Democratic Party.

The 2012 ANES pre-election survey includes 511 Black respondents. Using this survey, the authors report that 90% of African Americans identify as Democrats and 55% strongly so, compared to 39% and 11% of Whites. Yet, when the authors looked at a 7-point measure of ideology, only 47% of Blacks identify as liberal while 45% identify as conservative in the United States.

Given the mismatch between political ideology (measured using the liberal-conservative continuum) and partisanship, the authors turned to other ways to measure political ideology: egalitarianism, moral traditionalism, and ideal role of government. On egalitarianism and size of government, Blacks were indeed considerably more liberal than Whites; there was not significant difference between the groups on morality.

Despite the ideological underpinnings of these questions, they only weakly correlate with the standard measure of political ideology. The strongest correlation was between egalitarianism and political ideology – at just 0.18 Among Blacks, this correlation jumps to 0.42 for Whites. (Correlation coefficients give a measure of fit between two variables. If the two variables move up and down in concert, this is a perfect correlation of 1; if there is no connection the correlation is 0.) Further, support for bigger government was the only ideological measure that was a statistically significant predictor of partisanship, which may suggest a need to rethink how we conceptualize and measure ideology as it pertains to African Americans.

So could the Black Utility Heuristic offer the best explanation of the overwhelming support for Democratic candidates among Black voters? To test this, the authors looked at the connection between believing that what happens to other African Americans affects the survey respondent’s own life and Democratic affiliation. This connection was not significant, directly countering Dawson’s Black Utility Heuristic. On the other hand, an alternative measure assessing the importance of in-group racial identity predicted identifying as a Democrat among Blacks.

Hutchings and Jefferson thus conclude that African Americans do not vote Democrat because of their ideological identity as liberals, or because of notions of linked fate. Instead, strong support for activist government and the importance of in-group racial identity seems to drive this trend.

Jul 2, 2014 | ANES, Elections, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ioannis Andreadis.

Ioannis Andreadis, a member of the Political Science faculty at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, studies elections in Europe. With a grant from the Fulbright Scholar Program, Andreadis was recently in residence at the University of Michigan’s Center for Political Studies (CPS) to learn more about the American National Elections Studies (ANES).

Andreadis started his academic career in 2007, after working as a computer scientist in his hometown’s municipality. His research focuses on elections, but the lack of a centralized database of election history in Greece presents obstacles to his work. With this in mind, Andreadis is interested to create a Greek version of the ANES – not only for the benefit of his own work, but for the benefit of other political scientists. Andreadis also plans to develop a centralized repository so that the data themselves can be easily disseminated to researchers.

Andreadis started his academic career in 2007, after working as a computer scientist in his hometown’s municipality. His research focuses on elections, but the lack of a centralized database of election history in Greece presents obstacles to his work. With this in mind, Andreadis is interested to create a Greek version of the ANES – not only for the benefit of his own work, but for the benefit of other political scientists. Andreadis also plans to develop a centralized repository so that the data themselves can be easily disseminated to researchers.

A Greek version of the ANES faces some special challenges. Funding is limited in light of the country’s recent financial crisis. But this challenge has led to methodological innovation. Instead of relying on traditional data collection methods such as phone surveys, Andreadis has been developing web-based questionnaires. In 2007, 2009, and 2012, Andreadis ran such a web-based survey for the Hellenic (Greek) Candidate Study, and in 2012 he used his web survey infrastructure to collect data for a voter study which was organized as a mixed mode survey.

Andreadis’ efforts are also part of the True European Voter project, a COST Action to track election data across time and across Europe. Participating countries include Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

In addition to his interests in adapting ANES to the Greek political realm, Andreadis also combines his computer programming skills and interest in elections. Anreadis both designs and studies Voting Advice Applications (web-based platforms that aim to inform citizens about the electoral process, with emphasis on the positions of candidates and parties on issues related to electoral competition). In particular, Andreadis created and oversees the Voting Advice Application HelpMeVote, which was used by more than 480,000 voters during the May 2012 Greek Parliamentary Elections. HelpMeVote has also been used in Albania, Iceland, and during the 2014 elections for the European Parliament.

CPS and ANES are thrilled to have have had Andreadis visit, and look forward to the progress of his initiatives in support of election studies and political science research in Greece and beyond.

Jun 24, 2014 | ANES, Elections, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Spencer Piston.

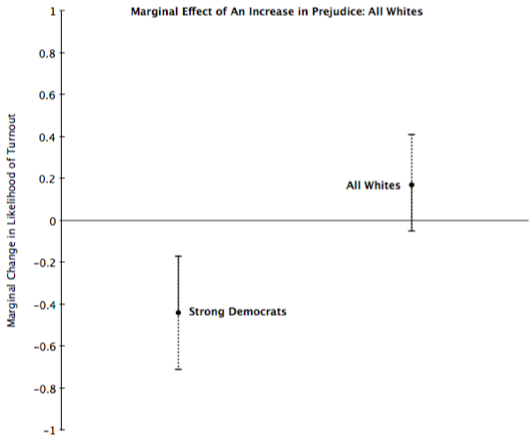

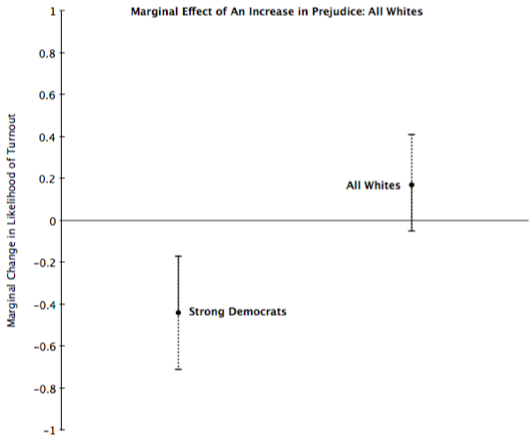

The 2008 election in the United States featured the first black major party presidential candidate in U.S. history – Barack Obama. Obama won in a historic election. But was his victory margin narrower than it could have been? In particular, did racial prejudice erode Obama’s vote share among those whites expected to vote for him: strong Democrats?

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Center for Political Studies (CPS) affiliate and Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan Spencer Piston explored this question with co-author Yanna Krupnikov (Northwestern University) in a recent article published in Political Behavior.

The researchers identify a gap in the field. Where previous work focuses on the connection between prejudice and vote choice, few studies have considered the relationship between prejudice and turnout on Election Day.

The researchers evaluate the relationship between racial prejudice, strength of party identification, and turnout. They are especially interested in a situation in which a white voter, high in racial prejudice, is faced with a black candidate from her party. How will the voter vote? In this scenario, racial prejudice is pitted against party identification.

Examining 2008 data from the American National Election Studies and replicating their analyses with survey data from a wave of a 2007-2008 Associated Press-Yahoo! News-Stanford University study, the authors find that highly partisan and prejudiced voters often address the tension embodied in a black candidate from their party by not turning out to vote. Interestingly, the authors also test if this group would instead vote for the white Republican presidential candidate John McCain. They would not. This is because they cannot compromise on race or partisanship. Unable to compromise, they instead choose not to vote.

These findings have significant implications for American elections. The authors conclude, “Racial prejudice undermines black candidates’ efforts to mobilize strong partisans.”

Spencer Piston will join Syracuse University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Political Science.

In The American Voter, Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes became part of this behavioral revolution as they considered audience traits in the context of politics. The main argument of the book holds that most American voters cast their ballots on the basis of party identification. Specifically, voter decisions pass through a funnel. At the opening of the funnel is party identification. With this lens, voters process issue agenda. They then narrow down to evaluate candidate traits. Finally, at the small end of the funnel is vote choice. This understanding of voters encompasses the “Michigan Model.”

In The American Voter, Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes became part of this behavioral revolution as they considered audience traits in the context of politics. The main argument of the book holds that most American voters cast their ballots on the basis of party identification. Specifically, voter decisions pass through a funnel. At the opening of the funnel is party identification. With this lens, voters process issue agenda. They then narrow down to evaluate candidate traits. Finally, at the small end of the funnel is vote choice. This understanding of voters encompasses the “Michigan Model.”