Information about the wealth gap between Blacks and whites increases Americans’ awareness of disparity, but does little to increase their support for affirmative action, reparations

Since the “racial reckoning” of 2020, Americans have become increasingly aware of the barriers Black people face to accessing economic opportunities and achieving intergenerational mobility.

But despite widespread knowledge that racial inequality exists, even among liberal, white Americans, the public is radically uninformed about the depths of one of the most profound racial disparities: the racial wealth gap.

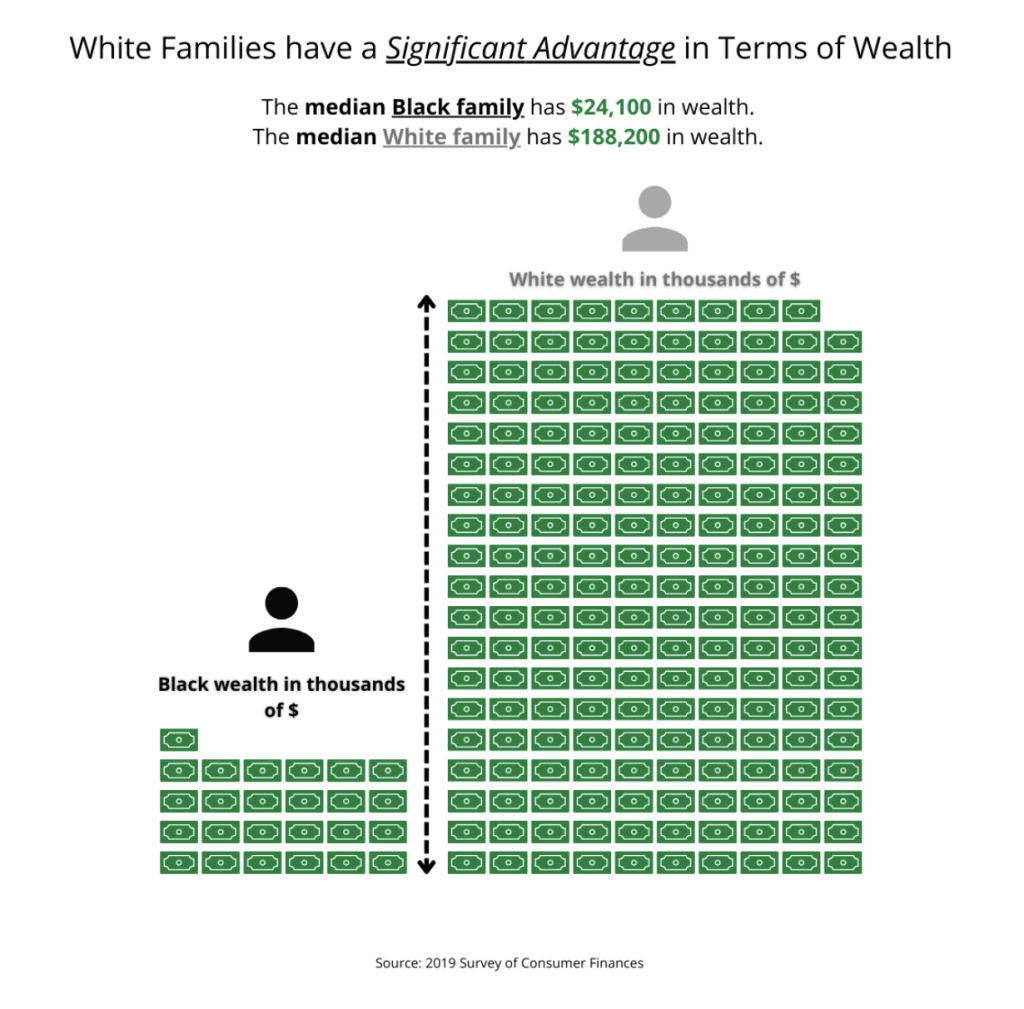

According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, which collects nationally representative data on American households, the median white family has about 8 times more wealth (that is, total assets minus total debts) than the median Black family. And, despite popular perceptions of education as the vehicle for eliminating racial disparities, education does little to diminish the gap between Blacks and whites. The median white family where the household head did not finish high school has virtually the same wealth as the median Black family where the household head earned a bachelor’s degree. In other words, a Black American has to graduate from college to access the same level of wealth as a white high school dropout.

If you find these numbers startling and even difficult to believe, you are not alone.

Since 2020, my research team, which includes Vincent Hutchings, Kamri Hudgins, and Sydney Carr, has been learning what happens when we correct misperceptions of the racial wealth gap. Does informing people about the size of the racial wealth gap influence opinions about policies to address the gap? How does the public react to information about the racial wealth gap?

Using a novel survey experiment fielded on three nationally diverse samples, we found that exposing both Black and white Americans to information about the size of the racial wealth gap increases their awareness of this disparity– but exposure to this information does little to increase their support for race-targeted social and economic policies like affirmative action and reparations.

For example, among white participants, exposure to our racial wealth gap information treatment increased awareness of the size and severity of the racial wealth gap by, on average, 7 to 18% across the two studies. However, exposure to the same information did not significantly increase support for race-targeted policy changes to reduce the racial wealth gap among white or Black participants.

In contrast, our treatments did increase support for race-neutral equity policies like baby bonds, a program that would fund a trust for every newborn child to establish a baseline level of wealth for all Americans. When informed that Black college graduates have the same level of wealth as white high school dropouts, both liberal and conservative white Americans’ support for baby bonds increased significantly. For conservatives, support increased by 12% moving from a baseline of .41 (indicating weak opposition) to .53 (indicating weak support). For liberals, support increased by 11% moving from .71 (strong support) to .82 (very strong support).

But economists argue that race-neutral programs like baby bonds or canceling student loan debt would not be nearly enough to close the racial wealth gap. For example, Duke University economist William Darity, Jr. proposes that only a comprehensive reparations program requiring “the full resources of the federal government” to redistribute wealth to Black Americans would be sufficient for closing the gap.

Those who believe legislative action on reparations is urgently needed will find the political momentum behind it at the federal level to be insufficient. President Joe Biden made the most progress on this issue of any president in history when he proposed a commission to study whether or not reparations should be paid to Black descendants of the enslaved. But the bill has effectively died in committee and there have been no votes on the House floor regarding the commission or any other reparations policies. While several states and localities have made more progress toward providing reparations to Black residents and, in some instances, (like Evanston, Illinois) have even begun issuing payments, these programs will not resolve the Black wealth crisis nationwide.

As this project develops, we hope to probe public opinion on other racial disparities, including the racial gap in rates of maternal mortality, and increase scholarly and public understanding of what it takes to move the public towards action on racial inequality.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

This post was written by Zoe Walker. Tevah Platt contributed to its development.

Zoe Walker is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Ford Foundation Predoctoral Fellow. Her dissertation research, supported by the Russell Sage Foundation, considers how beliefs about economic opportunity influence perceptions of racial inequality and support for racially redistributive policies among Black Americans.

Sydney Carr, Kamri Hudgins, and Zoe Walker are all Next Generation scholars of the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research and were consecutive recipients of the Hanes Walton, Jr. Endowment for Graduate Study in Racial and Ethnic Politics at the Center for Political Studies.

Hanes Walton, Jr. of the Center for Political Studies transformed the study of Black politics and helped establish it as a subfield of political science. The 2024 Hanes Walton Jr. Lecture at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research will be presented by Christian Davenport on Feb. 1.