Sep 3, 2013 | Current Events, Elections, Foreign Affairs, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Allen Hicken.

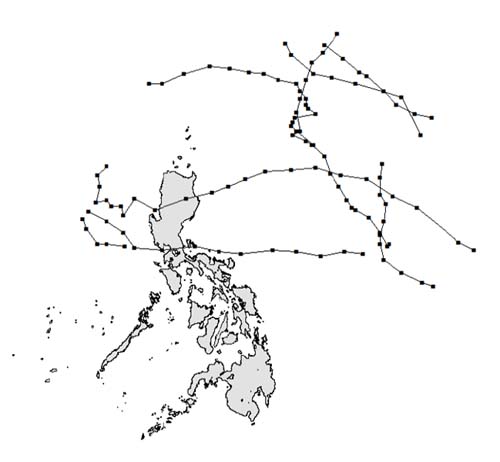

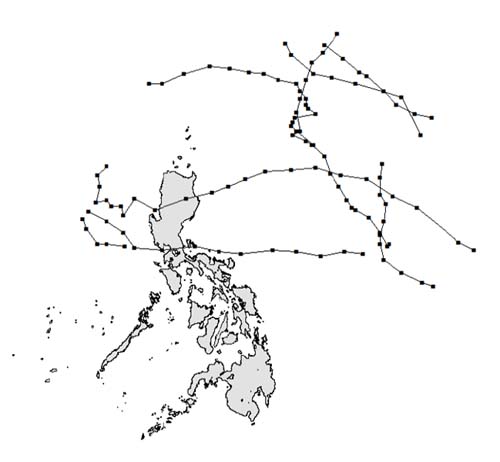

Each year, 30 typhoons and tropical storms batter the Philippines. The damage costs between $17 and $19 million per year, nearly 10 percent of the nation’s GDP. The Japanese Meteorological Agency developed a storm tracking system that measures date, time, location, wind speed, barometric pressure, and storm type every six hours. The map below displays the paths of storms striking the country in 2010.

In addition to tracking typhoons, could this map also help gauge the role of political affiliations in the distribution of public resources, a.k.a., pork barreling? Enter the work of Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher Allen Hicken, who is also Director of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies and Associate Professor of Political Science. In a forthcoming paper, “Pork & Typhoons: The Political Economy of Disaster Assistance in the Philippines,” Hicken, along with graduate students James Atkinson and Nico Ravanilla, developed a new approach to studying pork barreling.

Specifically, the research uses a storm index created by University of Michigan faculty member Dean Yang to create a baseline of expected relief fund distribution and trace variations by political ties. The Philippines’ democracy is both one of the oldest and weakest in Asia. Political clans are central to Filipino political life. The research considers political ties both in terms of party links and clan connections between a politician and a region.

To what extent do political calculations affect the allocation of government disaster reconstruction funds? The results show that need does indeed impact relief received. However, the authors also find that, “Political ties between members of congress and local mayors, especially clan ties, increase per capita targetable funds allocated to that municipality.” Thus, tracking typhoons can expose pork barreling.

Though typhoons and clan ties may be unique to the Philippines, natural disasters and pork barreling are global phenomena. Thus, the innovative methodology pioneered in this paper could be applied to other nations to increase understanding of political ties and resource allocation.

Aug 29, 2013 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Ken Kollman.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

On July 22, 2013, the European Union (EU) declared that the military wing of Hezbollah was now on its list of terrorist organizations. This reversal of policy has implications for Hezbollah and the EU’s influence in parts of the Middle East.

Three events precipitated the change in policy by the EU. First, while Hezbollah denies involvement, most blame people in the group for a 2012 bus bombing in Bulgaria. Second, Hezbollah forces are fighting on behalf of Assad in Syria, while the EU is openly supporting the Syrian rebels. Three, a Lebanese Swedish man on Hezbollah’s payroll was charged and sentenced in 2013 for planning to attack Israeli tourists in Cyprus.

The declaration of Hezbollah’s military wing as a terrorist group took longer than many expected and came belatedly after years of prodding by the United States government. Decisive foreign policy decision making of this kind is difficult to achieve in the EU given its lack of a centralized executive with well-defined responsibilities for foreign affairs.

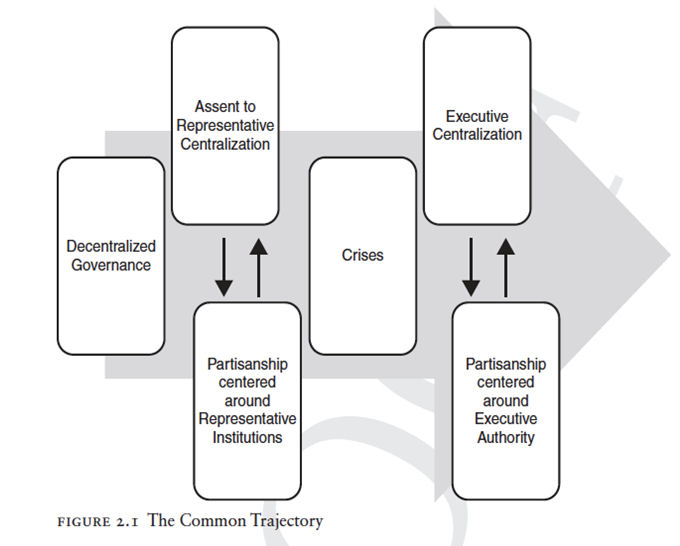

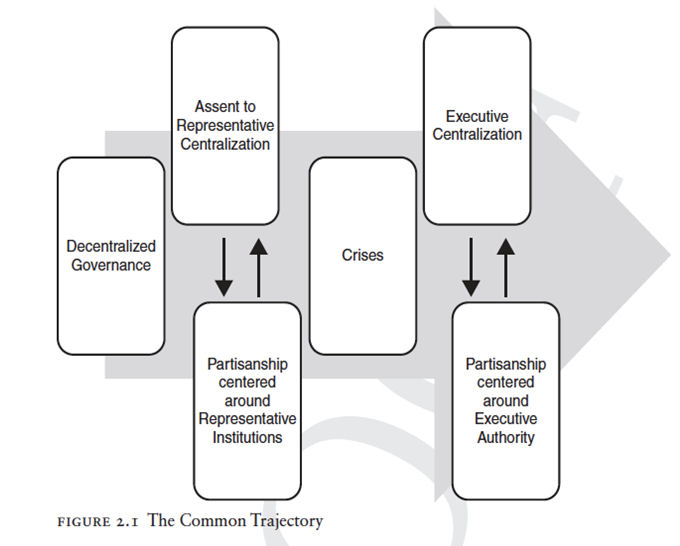

Ken Kollman, Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher and director of the International Institute at the University of Michigan, has a forthcoming book examining the histories of federated institutions like the EU to learn of the development of centralized executive power. In Perils of Centralization: Lessons from Church, State, and Corporation, Kollman dissects the histories of the U.S. government, the Roman Catholic Church, General Motors Corporation (GM), and the EU. In the book he argues that the EU is at a turning point. It has evolved what he calls representative centralization, which means that the countries of the EU still exert considerable authority over centralized decision-making. Unlike the U.S. government, which has tipped into what Kollman calls executive centralization, the EU countries, when they lack a consensus on matters like the Hezbollah listing, find many ways to delay unified decision-making. In the U.S. the subunit governments and subunit representatives have largely delegated to a single executive (the president) foreign policy decision-making power.

The Figure shown here from Kollman’s book shows the typical pattern for federations, but he notes that the EU is now poised between assent to representative centralization and executive centralization.

While Brussels exercises authority that supersedes a given nation on several key policy issues, the power is diffuse. When policy decisions are announced, for example, three or more leaders often stand behind the microphone, a symbol of both multiplicity and unclear jurisdictions. Executive power in the EU is not unified and often cannot be decisive.

The example of the lengthy process of Hezbollah’s listing and other similar examples showcase EU’s fragmented political power. Its halting evolution as a federated system leads to its precarious position as a potential player on the world stage.

Aug 16, 2013 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International, National

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Darrell Donakowski

Yesterday, The Washington Post released an internal report from the National Security Agency (NSA) revealing the agency broke its own privacy rules thousands of times per year since 2008. The source? Edward Snowden, former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) employee and analyst at NSA contractor Booz Allen. The Post release is the latest chapter in the story of Snowden and government trust.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In June and July of this year, UK’s The Guardian published a series of news articles revealing surveillance by NSA. The US charged Snowden with espionage and revoked his passport. On the lamb, Snowden flew to Hong Kong from Hawai’i. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange worked to broker asylum for Snowden in Iceland to no avail. Snowden moved onto Russia, residing in the transit zone of Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport for over a month. On August 1, Russia granted Snowden a one-year asylum. Snowden has an additional 20 applications out for asylum.

Snowden’s asylum prospects complicate US international relations. Obama canceled a summit with Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. Senator Lindsey Graham (R) called for a boycott of the 2014 Olympics in Sochi, Russia, a plan rejected by Speaker of the House John Boehner. On July 2, Bolivian President Evo Morales’ plane was denied entry to several European nations’ airspace and airports amid rumors Snowden was on board, stressing European and US relations with several Latin American countries (Bolivia, Venezuela, and Nicaragua granted Snowden’s request for asylum).

In the wake of the story, questions turned into a debate in the media as to how to understand Snowden. Leaker? Traitor? Punk? The American public appears to see Snowden as a whistleblower. Further, the media linked the immediate fallout – plus the IRS scandal and Benghazi trials – with an 8 point drop in Obama’s approval rating. Hovering around 44%, Gallup shows Obama’s recent ratings below the presidential average of 54%.

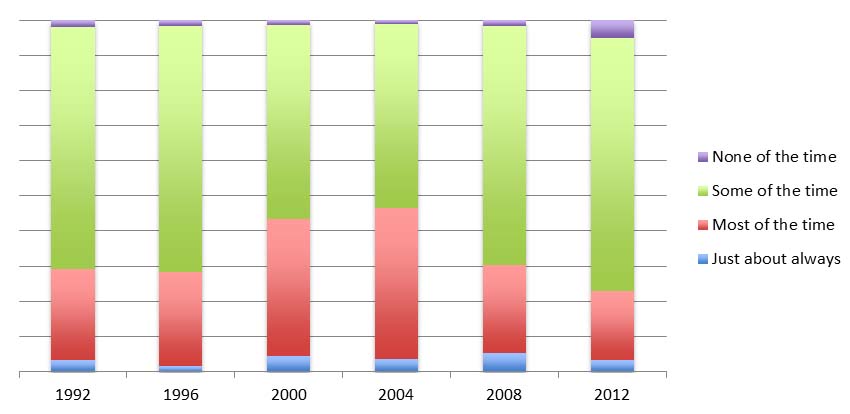

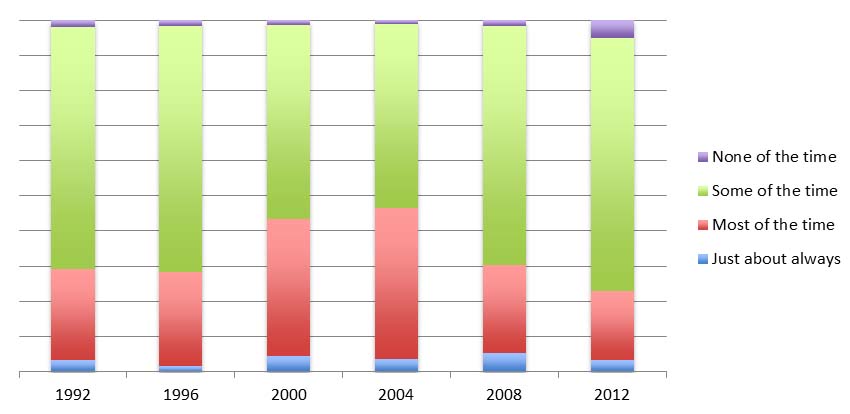

But what about trust in the government in particular? The American National Election Studies offers a glimpse of trust in government across time. Asked how much of the time the government does what is right, respondents could choose between three answers: “just about always,” “most of the time,” and “some of the time,” with some respondents volunteering “none of the time.” The graph below displays the spread across time and across answers.

How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Washington to do what is right?

While this graph does not correspond to the Snowden event, it contextualizes the attributed decrease in trust across time. That is, the decrease in trust attributed to the leak would correspond to a generally decreasing trend.

Last week, Obama announced an overhaul of NSA surveillance. Though Obama refuses to acknowledge Snowden as a catalyst for the changes, Assange claims the move vindicates Snowden. The move suggests a push for transparency and restored trust in the government.

Aug 7, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Christian Davenport

Photo credit: Thinkstock

On August 5, 2013, a Turkish court convicted 275 people, including ex-military officers, of plotting to overthrow Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Though the court case took five years, the verdict comes at a tenuous moment in Turkish politics, deepening the divide between Ergodan and critics.

This summer, protests erupted across Turkey. Initially a movement against the planned development of Taksim Gezi Park, a rare patch of green in the city of 13.5 million, the uproar spread as general government dissent. A small fraction of the protestors resorted to violence. The government cracked down with force in response. Erdogan initially presented a mixed message, alternating between ultimatums, violence, and agreeing to meet with protestors. By the end of June, his message and tactics showed more force. More than 5,000 were injured and 4 killed. Doctors tending to the wounded were arrested, a fact verified by Erdogan. The government also worked to block social media, blamed for spreading the word. And Ergodan lashed out against international media, claiming false representation.

The violence is noteworthy in a country with an emerging democracy with dreams of ascension into the European Union. But is the violence really a surprise?

Research on violent dissent by Center for Political Studies researcher Christian Davenport sheds light on the current situation in Turkey, through his work on the power of democracy to ease repression. A central thesis of the work asserts the calming power decreases in the face of violent dissent. Using a cumulative index created by Polity, Davenport published an article with David Armstrong. The authors find that lower levels of democracy, unlike higher levels of democracy, have no calming influence on violent repression.

A graph from Polity shows the trend over time, illustrating that Turkey is not just a weak democracy, but emerging in many senses. Davenport’s work helps us understand that the violent reaction in response to anti-government protests is not surprising given Turkey’s relatively weak democracy. Turkey’s democracy is weak enough that it cannot pacify repression of this sort.

The EU passed a resolution in response to the violent repression. Erdogan fired back that the EU should, “know [its] place!” The repression was not quelled by Turkey’s weak democracy, nor it seems the EU, both of which are challenged by the violence.

Interestingly, the protests in Turkey are credited with inspiring anti-government protests in Brazil. And while initial protests in Brazil were met with tear gas and rubber bullets, the number of injuries rests near 100. Prime Minister Dilma Rousseff even supported the right to protest, while expressing interest in listening: “These voices need to be heard, my government is listening to these voices for change.” Yet the protests continue and are forecasted to continue up to the 2014 World Cup, hosted in Brazil and a source of dissent.

Jul 2, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Christian Davenport (@engagedscholar).

On June 13, 2013, news of the political terror in Syria reached a breaking point. Under President Bashar al-Assad, 92,000 Syrians have been killed. Recent evidence suggests the use of chemical warfare, including sarin gas. Though the civil war has festered for years now, the global community is only beginning to respond. In the wake of this new information, the White House ordered aid to select rebels. On June 18, 2013, the G8 summit supported urgent peace talks in Geneva with Syria. Regardless of how the world’s super powers intervene, the violence is staggering. How can we understand such repressive strategies?

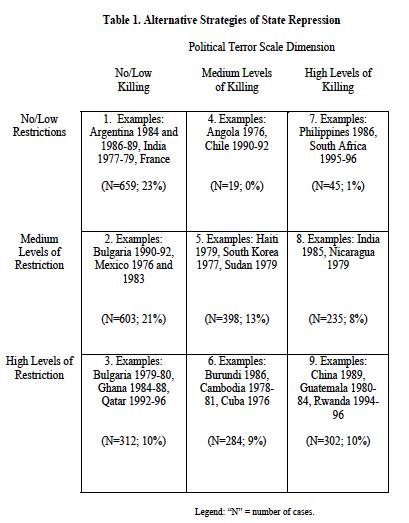

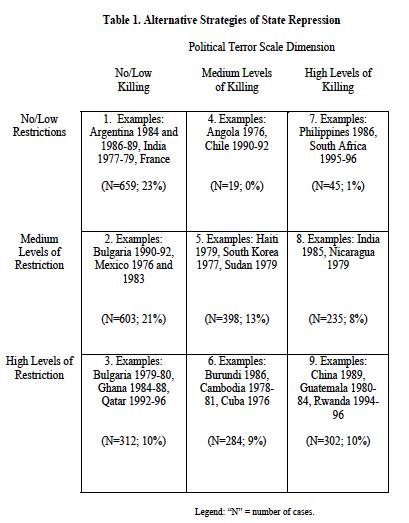

Center for Political Studies researcher Christian Davenport’s work on violent dissent offers insight into Syria’s present state. Davenport’s research uses the Political Terror Scale to operationalize physical torture and elimination of citizens. Both Amnesty International and the U.S. State Department rate Syria at the highest end of this scale, with a 5, defined as: “terror has expanded to the whole population. The leaders of these societies place no limits on the means or thoroughness with which they pursue personal or ideological goals.”

Davenport creates a conceptualization that goes one step further. The resulting grid plots level of restriction against level of killing. Syria rates high on both accounts, making the current situation comparable to other notorious times and places: China in 1989, Guatemala in 1980, and Rwanda from 1994-1996.

Davenport creates a conceptualization that goes one step further. The resulting grid plots level of restriction against level of killing. Syria rates high on both accounts, making the current situation comparable to other notorious times and places: China in 1989, Guatemala in 1980, and Rwanda from 1994-1996.

Davenport’s research emphasizes the dire nature of the situation in Syria. We have little insight into how such activities are ended (something that is sorely needed), but one thing that we do know is that within such situations political leaders are not as sensitive to external policies that under normal circumstances would seem quite costly.