Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Ken Kollman.

On July 22, 2013, the European Union (EU) declared that the military wing of Hezbollah was now on its list of terrorist organizations. This reversal of policy has implications for Hezbollah and the EU’s influence in parts of the Middle East.

Three events precipitated the change in policy by the EU. First, while Hezbollah denies involvement, most blame people in the group for a 2012 bus bombing in Bulgaria. Second, Hezbollah forces are fighting on behalf of Assad in Syria, while the EU is openly supporting the Syrian rebels. Three, a Lebanese Swedish man on Hezbollah’s payroll was charged and sentenced in 2013 for planning to attack Israeli tourists in Cyprus.

The declaration of Hezbollah’s military wing as a terrorist group took longer than many expected and came belatedly after years of prodding by the United States government. Decisive foreign policy decision making of this kind is difficult to achieve in the EU given its lack of a centralized executive with well-defined responsibilities for foreign affairs.

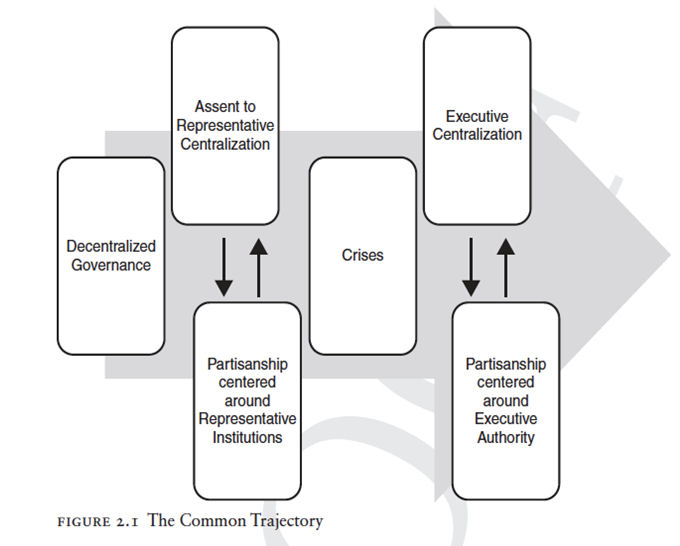

Ken Kollman, Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher and director of the International Institute at the University of Michigan, has a forthcoming book examining the histories of federated institutions like the EU to learn of the development of centralized executive power. In Perils of Centralization: Lessons from Church, State, and Corporation, Kollman dissects the histories of the U.S. government, the Roman Catholic Church, General Motors Corporation (GM), and the EU. In the book he argues that the EU is at a turning point. It has evolved what he calls representative centralization, which means that the countries of the EU still exert considerable authority over centralized decision-making. Unlike the U.S. government, which has tipped into what Kollman calls executive centralization, the EU countries, when they lack a consensus on matters like the Hezbollah listing, find many ways to delay unified decision-making. In the U.S. the subunit governments and subunit representatives have largely delegated to a single executive (the president) foreign policy decision-making power.

The Figure shown here from Kollman’s book shows the typical pattern for federations, but he notes that the EU is now poised between assent to representative centralization and executive centralization.

While Brussels exercises authority that supersedes a given nation on several key policy issues, the power is diffuse. When policy decisions are announced, for example, three or more leaders often stand behind the microphone, a symbol of both multiplicity and unclear jurisdictions. Executive power in the EU is not unified and often cannot be decisive.

The example of the lengthy process of Hezbollah’s listing and other similar examples showcase EU’s fragmented political power. Its halting evolution as a federated system leads to its precarious position as a potential player on the world stage.