Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Christian Davenport.

Department of Political Science Professor and Center for Political Studies faculty member Christian Davenport’s latest work examines transitional justice – judicial and non-judicial actions implemented by governments to deal with legacies of human rights abuses. These actions can typically include criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations, and various kinds of institutional reforms.

In Transitional Injustice: Subverting Justice in Transition and Postconflict Societies, published in the Journal of Human Rights, Davenport and Cyanne Loyle, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Indiana University, coin the term transitional injustice to describe governments that implement transitional justice without maintaining interest in truth, peace, or democracy. Instead, their intention is to promote denial and forgetting, violence, and legitimize authoritarianism.

The normative perspective of transitional justice assumes that legal processes following political conflict are implemented with the goal of reconciliation, peace, and democratization. It is assumed that “good” processes will lead to “good” outcomes. However, this assumption makes it possible for governments to hide behind transitional justice using similar legal institutions to advance detrimental aims. Davenport and Loyle argue that governments can use trials, truth commissions and amnesty without maintaining an interest in these goals, but rather to promote transitional injustice, i.e. denial, violence, and legitimizing state repression. Transitional injustice is particularly problematic for those interested in promoting justice processes because it reveals how institutions can be subverted for different purposes, often with international consent.

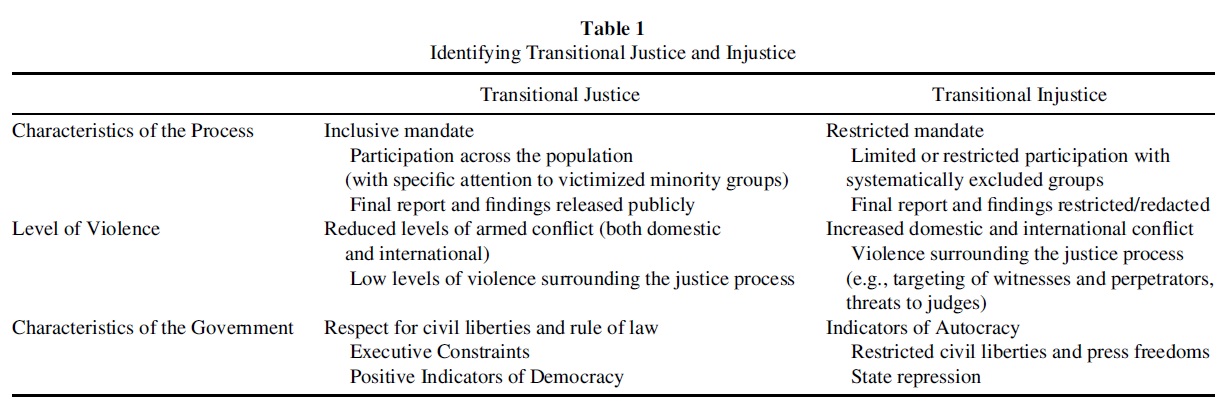

The article not only provides conceptual clarity on identifying differences but also provides indicators by which policy makers and scholars can determine if transitional injustice is taking place. In particular, policy makers can identify transitional injustice by relying on three key dimensions: (1) characteristics of the process, (2) levels of violence in the postconflict society, and (3) characteristics of the government (Table 1). These components allow government intentions and the potential for subversion of justice to be evaluated.

First, the degree of openness of the process is an indicator of the objectives of the government and the possibility for positive outcomes from the process. One could gauge the promotion or subversion of truth-telling by the degree to which distinct actors are integrated into the justice process, given an opportunity to participate, to draft, review and edit relevant decisions, as well as veto aspects of the process. Transitional justice should have a broad mandate incorporating all types of violations experienced during the conflict. Transitional injustice, however, reveals itself as a more closed process with a limited mandate and exclusion of certain individuals and groups.

The second indicator is the level of violence surrounding the process and the country. While violent events often linger in postconflict societies, the presence of transitional justice should lead to reduced levels of violence in the society overall. Transitional injustice however, is accompanied by violence internationally, domestically, and surrounding the process itself.

Third, characteristics of the government can be assessed by the level of democracy and the country’s present trajectory. Breaking from a past autocratic regime does not ensure that the new regime will be more democratic. Rather, the intentions of the regime should be assessed through institutional and behavioral indicators of democracy. The degree to which a justice process legitimates a democracy through open and frequent elections, diverse and representative political parties, and autonomous institutions is a valuable metric for understanding the general intent of those involved. Transitional justice should be accompanied by growing levels of democracy, while transitional injustice will accompany autocracy.

To more specifically illustrate how to identify transitional injustice, the article examines post-genocide Rwanda. On the surface, it appears that Rwanda’s approach to justice supports the normative aims of transitional justice. The Rwandan approach combines international, national, and local justice processes with the stated goals of truth and reconciliation, peace, and democracy. However, critics have called into question the ability of this justice package to accomplish those goals. Instead, it is being revealed that elements of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, national courts, and local justice processes have been used by the Rwandan government to promote denial, renewed violence, and the legitimization of an autocratic regime.

Regarding the openness of the process, the first dimension of transitional injustice, the space for justice in post-genocide Rwanda has been constricted through the support of targeted remembering, state-sanctioned scripted truths, and restricted access to justice. Instead of addressing all forms of conflict in Rwanda, the current justice package concentrates only on violence committed during the genocide. This strategy aims to direct attention to the successes of the government, namely ending the genocide, and away from its failures, mainly human rights violations and civilian massacres during the civil war and following the 1994 political transition.

Turning to the level of violence surrounding the process, far from reducing violence, the Rwandan approach to justice allows the government to increase domestic violence and international conflict. Violence has been a persistent component of the post-1994 Rwandan state, as in the aftermath of the genocide, a number of people were accused, tried and executed in a short period of time. By 2000, 348 people convicted of genocide crimes through the national courts were sentenced to death (Schabas, 2009), while the procedural fairness of many of those trials is questioned (Amnesty International, 2007). There has also been violence surrounding the justice processes themselves. In 2007 alone, the US State Department recorded 324 incidents of violence related to local justice processes, including killings of genocide survivors (US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2008). While the government has officially denounced the violence, it has been reluctant or unable to stop it.

The final dimension of transitional injustice, characteristics of the government, provides an example of the Rwandan justice system working to consolidate an authoritarian regime and restrict political participation. The Rwandan government is a far cry from a functioning democracy. While elections have been held, their validity has been questioned and the lack of a viable opposition party has essentially made the country a single-party state (Reyntjens, 2004; Davenport, 2007). Freedom House (2007) has characterized elections as “marred by bias and intimidation which precluded any genuine challenge to the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)”.

Attempts to launch rival political parties have been met with intimidation and, in some instances, violence. The restriction of viable political alternatives to President Kagame’s RPF has limited the electoral power of individual citizens. In the 2010 presidential election, three opposition candidates were excluded from the ballot and Paul Kagame was reelected by 93% of the vote.

In conclusion, Rwanda claims to support domestic and international efforts to collect information about what happened, to communicate the findings, and capture and punish those who were involved in previous violent action. Through these efforts, the government has argued that it will advance truth and reconciliation, prevent violence and facilitate democratization. Unfortunately, by concealing political motivations in the obstruction of justice proceedings and engaging in violent activity, the Rwandan government is doing irreparable damage to the development of truth, reconciliation, rule-of-law, and democracy. In order to acknowledge and challenge this subversion, the international community must recognize the ability of justice institutions to be used for less democratic aims. This research therefore aims to provide skepticism regarding the goals associated with transitional justice as well as indicators to evaluate the potential subversion of relevant processes.

References:

Amnesty International. (2007). Truth, justice and reparation: Establishing an effective truth commission. AI Index: POL 30/009/2007. Available: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4678de4a2.html.

Davenport, Christian. (2007). State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Freedom House. (2007). Countries at a Crossroad: Rwanda. Available: https://freedomhouse.org/report/countries-crossroads/2007/rwanda.

Reyntjens, Filip. (2004). Rwanda, ten years on: From genocide to dictatorship. African Affairs,103, 177-210.

Schabas, William A. (2009). Post-genocide justice in Rwanda. In After Genocide: Transitional Justice, Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Reconciliation in Rwanda and Beyond, Phil Clark and Zachary D. Kaufman (eds.). New York: Columbia University Press.