Post developed by Katie Brown and Timothy Ryan.

There are political issues and then there are moral political issues. Often cited examples of the latter include abortion and same sex marriage. But what makes a political issue moral?

Timothy Ryan, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Political Science and affiliate of the Center for Political Studies (CPS), explored this question in a recent article in The Journal of Politics. An extensive literature already asserts a moral vs. not moral issue distinction. Yet, there is no consensus in how to distinguish between moral and non-moral political issues. Further, trying to sort issues into these categories proves challenging. Many people assume that same-sex marriage is a moral issue, but does everyone see the issue in moral terms? Do people vary in terms of whether they see economic issues, such as Social Security reform and collective bargaining, with morality at stake?

In an attempt to define the divide between moral and non-moral, Ryan turned to the psychology literature. In particular, Ryan applies moral conviction to morality in politics. Moral conviction refers to topics that tap into an individual’s sense of right and wrong. According to the psychology literature, moral conviction leads to a different type of information processing. Moral conviction involves negative emotions, hostile opinions, and potential punitive actions.

Ryan then tests this concept as it relates to political issues with two studies. In both studies, he measures the emotions stimulated by moral conviction. He finds that moral conviction evokes negative emotions toward political disagreement. He also finds that both traditionally moral issues (like abortion or same sex marriage) and traditionally non-moral issues (like labor relations or Social Security) can both illicit moral conviction.

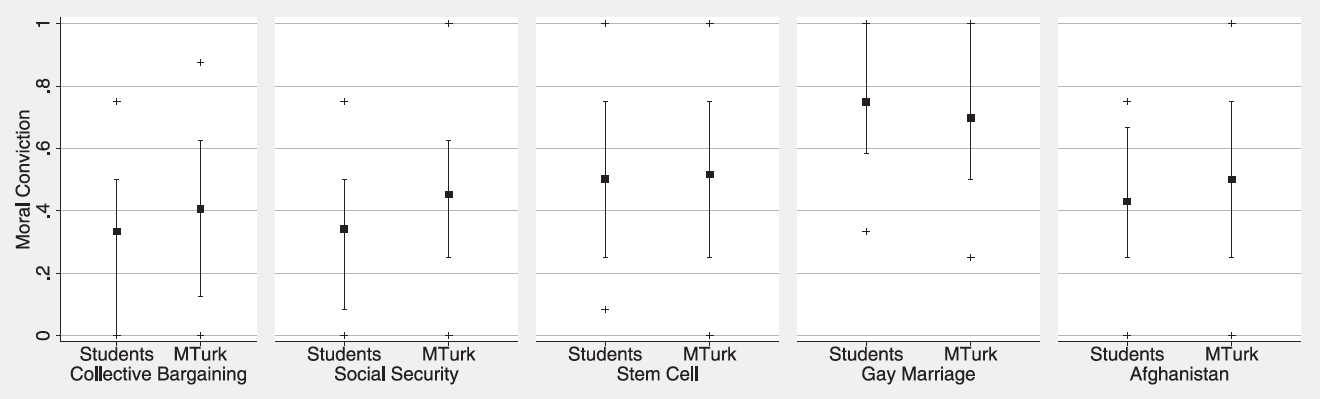

The graph below displays the mean (the squares), the middle 50% (the bars), and the middle 80% (the dots) of moral conviction for five different political issues. As we can see, moral conviction varies a lot for both economic and non-economic issues. Of course many people see same-sex marriage as a matter of right and wrong, Yet, many also see Social Security reform in the same way. The upshot is that, when it comes to deciding which issues are moral, an important part of the answer depends on the individual.

Distribution of Moral Conviction Variable

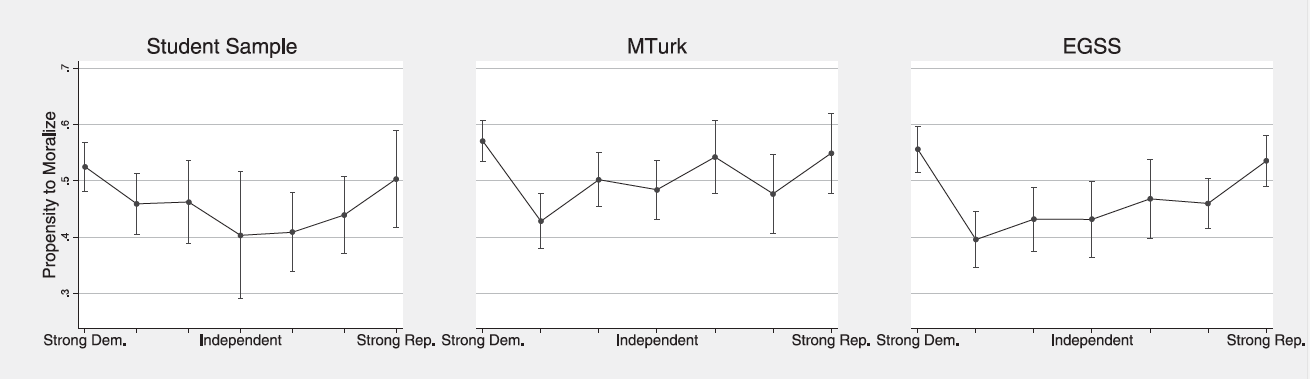

Ryan’s article also challenges a common assumption: the assumption that moral fervor in politics comes more from the right than the left. In the article, he examines propensity to moralize several political issues. The result? Liberals and conservatives moralize in equal measure. The figure below illustrates this with three separate samples: students, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk respondents, and Evaluations of Government and Society Study (EGSS) respondents.

Moral Conviction by Partisanship

Taken together, Ryan’s findings suggest that the response of moral conviction may be more important than distinguishing between inherently moral and non-moral political issues. Rather, all issues can produce a moral conviction response, depending on the person. Ryan concludes that, “in terms of the underlying psychology, Social Security is just as moralized for some people as Abortion is. Morality is in the eye of the beholder.”

In the fall, Ryan will continue his research on morality in politics when he joins the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as Assistant Professor of Political Science.