By Nicholas Valentino, James Newburg and Fabian Neuner

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Dog Whistles to Bullhorns: Racial Rhetoric in Presidential Campaigns, 1984-2016” was a part of the session “Framing Politics: The Importance of Tone and Racial Rhetoric for Framing Effects” on Friday, August 31, 2018.

Political candidates’ use of coded language to express controversial attitudes on race is nothing new – but is it more common than in the past? Nicholas Valentino, James Newburg, and Fabian Neuner analyzed data from 1984 to the present that showed campaign rhetoric in 2016 included more racial rhetoric, negative racial group outreach, and negative mentions of racial groups than any other campaign they studied.

Beginning in 1968 through the late 1990s, the expression of explicitly racist attitudes seemed to be in decline, although racially charged imagery was still used in the news and media. While the rhetoric became subtler, prejudicial attitudes were still expressed through “racially coded” language. Over time, issues like crime, welfare, and immigration evoked negative racial stereotypes that could impact political choices without explicitly mentioning race.

Beginning in 1968 through the late 1990s, the expression of explicitly racist attitudes seemed to be in decline, although racially charged imagery was still used in the news and media. While the rhetoric became subtler, prejudicial attitudes were still expressed through “racially coded” language. Over time, issues like crime, welfare, and immigration evoked negative racial stereotypes that could impact political choices without explicitly mentioning race.

The shift to less directly rhetoric is important because implicit references to race and racial stereotypes may have a greater impact on perceptions than explicit ones do. The authors of this study note that previous research shows that people may dismiss obvious appeals to racial bias, while actually being influenced by more subtle or coded language. They note that the strength of this effect is uncertain, and that recent studies show respondents more likely to accept explicit racial rhetoric.

After Barack Obama’s election in 2008, racially charged discourse became more explicit, shocking some Americans. It was impossible not to notice the change in the tone of racial language in the election of 2016. But when exactly did this shift occur? Did it happen gradually or all at once?

To answer these questions, the authors examine trends in racial rhetoric reported in the news between 1984 and 2016. They set out a hypothesis: If changes in rhetoric happened more gradually over time as a result of partisan realignment, they should see trends in the use of explicit racial rhetoric that predate the 2016 campaign, and perhaps even prior to 2008. If, on the other hand, the 2016 election and the candidacy of Donald Trump is the major cause of shifts in discussions of race and ethnicity in mainstream American politics, they would expect explicit group mentions, especially hostile ones, to spike in 2016.

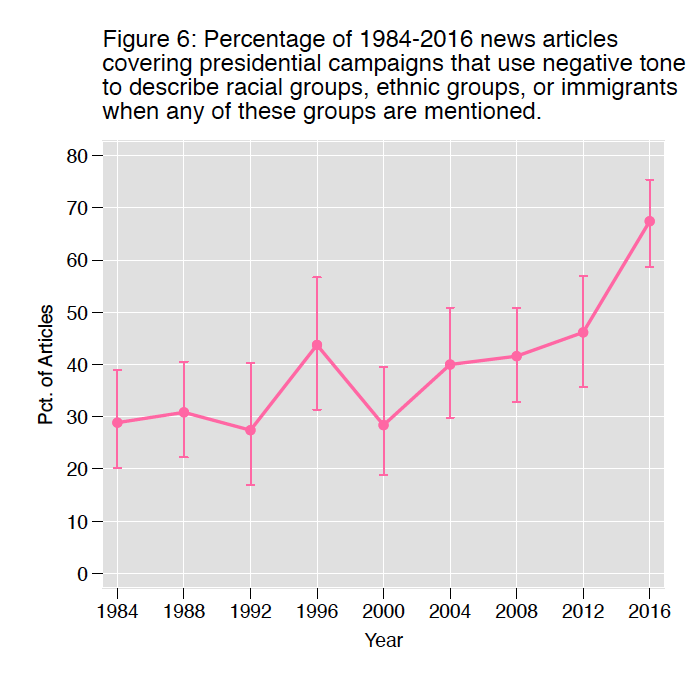

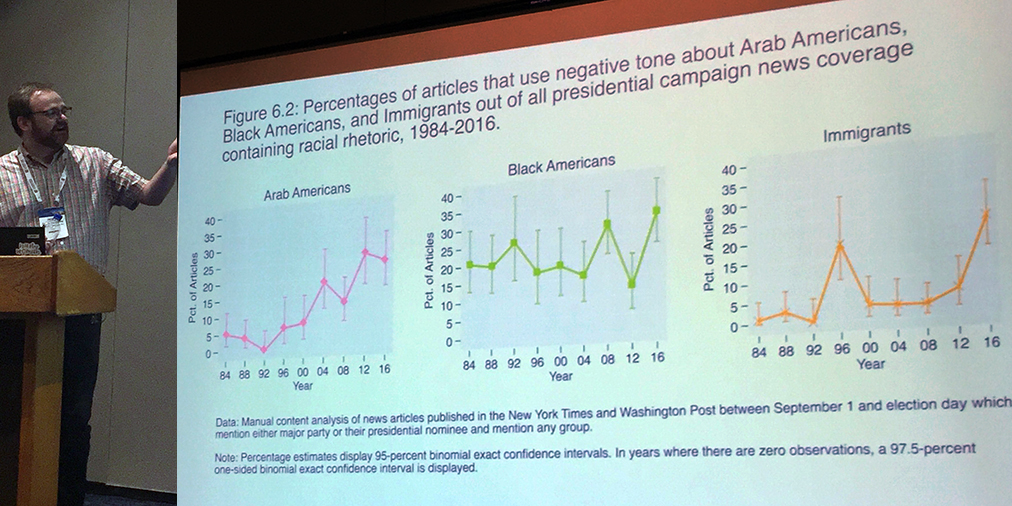

The researchers conducted a rigorous analysis of thousands of articles published in the New York Times and Washington Post between September 1 and Election Day during every presidential election year from 1984 to 2016. They found that while mentions of race were high throughout the study period, racial rhetoric spiked in 2016, especially with regard to immigrants and immigration.

Significant moments of presidential campaigns track with the rise and fall of explicit mentions of race in the news. As Republicans made electoral gains among Southern Whites, racial language reached a peak; during the more moderate campaigns of Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, racial language declined. Race became more prominent with the historic election of Barack Obama in 2008, but declined when Obama avoided discussions of race during his reelection campaign. The authors find that 2016 was unique in the high number of explicitly negative racial statements, but that partisan realignment had been causing this change had also been driving up the acceptability of these types of messages over several years.

They found that while the total amount of group coverage did not rise sharply until 2016, the coverage that was dedicated to groups got more negative gradually over time. Notably, an important factor in the secular increase of racial rhetoric was negative language describing Arab Americans, Latinos, and Immigrants in recent years. As American demographics continue to change and non-white groups grow in numbers and political strength, these trends in political language will grow even more significant.