Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Stuart Soroka

When you think of a Prius, what political party comes to mind? What about country music? Increasingly, Americans associate partisan leanings with otherwise non-political objects. Dan Hiaeshutter-Rice, Fabian G. Neuner, and Stuart Soroka examine the consequences of these associations in their paper “Divided by Culture: Partisan Imagery and Political Evaluations”, which they will present at the Midwest Political Science Association meeting on Saturday, April 6, 2019.

The cultural and political divide in America receives considerable media and scholarly attention. Republicans and Democrats have different preferences for everyday things like cars and drinks – most people are familiar with stereotypes of latte-drinking liberals or truck-loving conservatives. These differences even extend to their children’s names, the places they live, and the amount they give to charity.

The authors of this paper took a closer look at the extent to which non-political objects, activities, and places are associated with partisanship and ideology. Participants in the study were first prompted to list objects and activities they associate with either liberalism or conservatism. Following this open-ended question, respondents were asked to rate a list of 26 objects and activities based on ideology or partisanship.

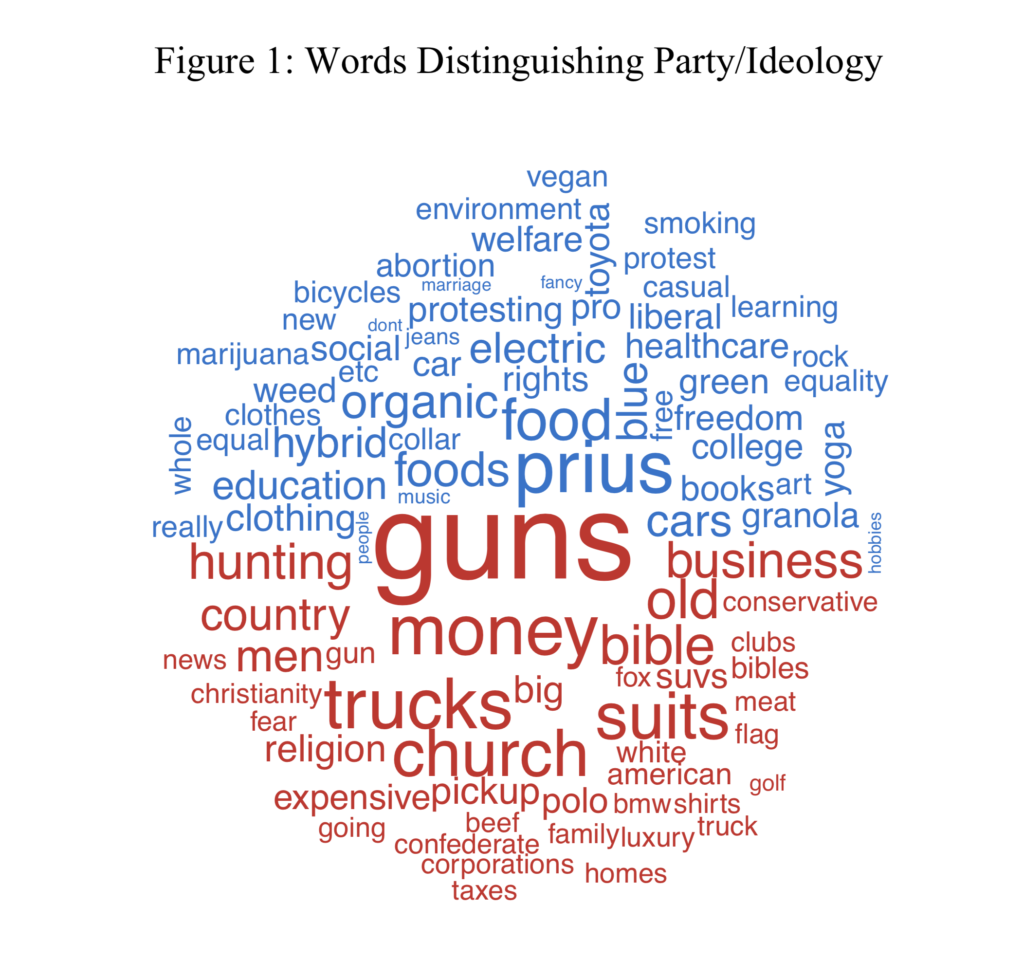

The results of the open-ended question are illustrated in the figure below, which shows the words most strongly associated with Democrats (blue) and Republicans (red). The figure makes clear the ease which which respondents name objects and activities often associated with the two partisan groups.

Hiaeshutter-Rice, D., Neuner, F., Soroka, S. 2019, “Divided by Culture: Partisan Imagery and Political Evaluations”, paper presented to the 77th Annual MPSA Conference, Chicago, IL, April 4-7, 2019.

In subsequent studies, the authors examined respondents’ reactions to a series of photos of political candidates standing in front of different backgrounds, including a NASCAR race, an organic food store, and a shooting range. Not all treatments made a difference, but the shooting range (and another image of a gun shop) in particular affected the way that respondents perceived the candidates’ ideology and policy proposal.

As more politicians use social media to share images of their campaigns, it is essential to be aware of the ways in which voters evaluate candidates. Nonverbal political communication conveys information that can help shape public opinion and political behavior. Will voters be manipulated by objects and scenery in political messages? The authors suggest that even as respondents can attach partisanship to wide range of non-political activities, their candidate-photo experiment finds only limited effects of hypothetical press-conference backgrounds. They conclude on a comforting note: “The fact that voters are readily able to attach partisanship to objects and activities, but yet barely take this information into account when rating candidates and policies, may be good news for representative democracy.”