Mar 17, 2017 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

by Christopher Fariss and Kristine Eck

Christopher Fariss, University of Michigan and Kristine Eck, Uppsala University

Debate persists inside and outside of Sweden regarding the relationship between immigrants and crime in Sweden. But what can the data actually tell us? Shouldn’t it be able to identify the pattern between the number of crimes committed in Sweden and the proportion of those crimes committed by immigrants? The answer is complicated by the manner in which the information about crime is collected and catalogued. This is not just an issue for Sweden but any country interested in providing security to its citizens. Ultimately though, there is no information that supports the claim that Sweden is experiencing an “epidemic.”

In a recent piece in the Washington Post, we addressed some common misconceptions about what the Swedish crime data can and cannot tell us. However, questions about the data persist. These questions are varied but are related to two core issues: (1) what kind of data policy makers need to inform their decisions and (2) what claims can be supported by the existing data.

Who Commits the Most Crime?

Policymakers need accurate data and analytical strategies for using and understanding that data. This is because these tools form the basis for decision-making about crime and security.

When considering the reports about Swedish crime, certain demographic groups are unquestionably overrepresented. In Sweden, men, for example, are four times more likely than women to commit violent crimes. This statistical pattern however has not awoken the same type of media attention or political response as other demographic groups related to ethnicity or migrant status.

Secret Police Data: Conspiracy or Fact?

In the past, the Swedish government has collected data on ethnicity in its crime reports. The most recent of these data were analyzed by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention’s (BRÅ) for the period 1997-2001. The Swedish police no longer collect data on the ethnicity, religion, or race of either perpetrators or victims of crime. There are accusations that these data exist but are being withheld. Such ideas are not entirely unfounded: in the past, the Swedish police have kept secret—and illegal—registers, for example about abused women or individuals with Roma background. Accusations about a police conspiracy to suppress immigrant crime numbers tend to center around the existence of a supposedly secret criminal code used to track this data. This code is not secret and, when considered, reveals no evidence for a crime epidemic.

For the period of November 11, 2015 through January 21, 2016 the Swedish police attempted to gauge the scope of newly arrived refugees involvement in crime, as victims, perpetrators, or witnesses. It did so by introducing a new criminal code—291—into its database. Using this code, police officers could add to reports in which an asylum seeker was involved in an interaction leading to a police report. Approximately 1% of police reports filed during this period contained this code. It is important to note here that only a fraction of these police incident reports actually lead to criminal charges being filed.

The data from these reports are problematic because there are over 400 criminal codes in the police’s STORM database, which leads to miscoding or inconsistent coding. Coding errors occur because the police officers themselves are responsible for determining which codes to enter in the system. The police note that there was variation in how the instructions for using this code were interpreted. The data show that 60% of the 3,287 police reports filed took place at asylum-seeker accommodation facilities, and that the majority of the incidents contained in these reports took place between asylum seekers. Are these numbers evidence of a crime epidemic?

Is there any Evidence for Crime Epidemic in Sweden?

If asylum-seekers are particularly crime-prone, then we would expect to see crime rates in which they are overrepresented relative to how many are living in Sweden. Sweden hosted approximately 180,000 asylum-seekers during this period and the population of Sweden is approximately 10 million. Therefore, asylum-seekers make up approximately 1.8% of the people living in Sweden, while 1% of the police reports filed in STORM were attributed to asylum-seekers.

While the Code 291 data are problematic because of issues discussed above, the data actually suggests that asylum seekers appear to be committing crime in lower numbers than the general population and does not provide support for claims of excessive criminal culpability. There were four rapes registered with code 291 for the 2.5 month period, which we find difficult to interpret as indicative of a “surge” in refugee rape. We in no way want to minimize the impact that these incidents had on the individual victims, but considering wider patterns, we consider a rate of four reports of rape over 76 days for a asylum-seeking population of 180,000 as not convincing evidence of an “epidemic” perpetrated by its members.

There is no doubt that crime occurs in Sweden. This is a problem for Swedish society and an important challenge for the government to address. It is a problem shared by all other countries. There is also no doubt that refugees and immigrants have committed crimes in Sweden, just as there is no doubt that Swedish-born citizens have committed crimes in Sweden as well. But if policy initiatives are to focus on particular demographic groups who are overrepresented in crime statistics, then it is essential that the analysis of the crimes committed by members of these groups be based on careful data analysis rather than anecdotes used for supporting political causes.

The Government of Sweden’s Facts about Migration and Crime in Sweden: http://www.government.se/articles/2017/02/facts-about-migration-and-crime-in-sweden/

Christopher Fariss is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and Faculty Associate at the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan. Kristine Eck is Associate Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University.

Sep 1, 2016 | APSA, CLEA, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Catherine Allen-West in coordination with Diogo Ferrari

Diogo Ferrari, PhD Candidate, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “The Indirect Effect of Income on Preferences for Centralization of Authority,” was a part of the session “Devolution, Fragmented Power, and Electoral Accountability” on Thursday September 1, 2016.

One of the primary activities of any elected government is to decide how to allocate public funds for policies like health care and education. In countries that adopted a federal system – like the United States, Canada, Australia, Germany, and others – the central government usually has some policies that promotes distribution of fiscal resources among different jurisdictions, like among states or cities. Take Australia for example. The federal government collects taxes that are funneled to local governments in accordance with their needs. This diminishes the inequality between different Australian sub-national governments in their capacity to invest and provide public services. Brazil is another example. Brazil has a huge federal program that transfers resources from rich to poor states and whose goal is to reduce regional inequality. These federal governments can only continue to operate in this way, that is, promoting interregional redistribution, if the power to control fiscal resources is centralized. Therefore, there is a connection between interregional redistribution and centralization of authority.

Now, voters have different preferences about how the government should spend the fiscal resources. They have different opinions, for instance, to which degree taxes collected in one region should be invested in another region. Do voters that support interregional redistribution also prefer that the fiscal authority is concentrated in the hands of the federal government as opposed to the sub-national ones? Which characteristics determine the preference of voters regarding interregional redistribution and centralization of authority? How those preferences are connected?

(more…)

Sep 1, 2016 | APSA, Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Catherine Allen-West in coordination with Michael Robbins.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Passive Support for the Islamic State: Evidence from a Survey Experiment” was a part of the session “Survey and Laboratory Experiments in the Middle East and North Africa” on Thursday, September 1, 2016.

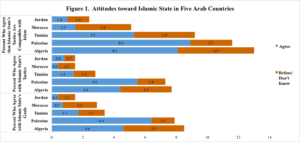

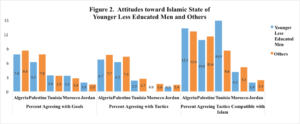

On Thursday morning at APSA 2016, Michael Robbins, Amaney Jamal and Mark Tessler presented work which explores levels of support for the Islamic State among Arabs, using new data from the Arab Barometer. The slide set used in their presentation can be viewed here: slides from Robbins/Jamal/Tessler presentation

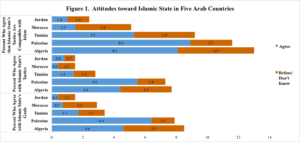

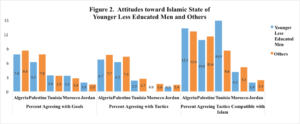

Their results show that among the five Arab countries studied (Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, Palestine and Algeria) there is very little support for the tactics used by Islamic State.

Furthermore, even among Islamic State’s key demographic – younger, less-educated males – support remains low.

For a more elaborate discussion of this work and the above figures, please see their recent post in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog, “What do ordinary citizens in the Arab world really think about the Islamic State?”

Mark Tessler is the Samuel J. Eldersveld Collegiate Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan. Michael Robbins is the director of the Arab Barometer. Amaney A. Jamal is the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton University and director of the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice.

Jul 18, 2016 | Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Linda Kimmel in coordination with Yuen Yuen Ang.

In June, Yuen Yuen Ang, Assistant Professor of Political Science and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate, spoke at a panel on “What Should Tomorrow’s Aid Agencies Look Like?” Jointly organized by the Global Development Network (GDN) and Center for Global Development, the event featured Professor Ang as a winning author of the GDN Essay Competition on “The Future of Development Assistance,” sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The contest invited “original and innovative thinking on development assistance.” An international jury of development experts selected thirteen winners out of 1,470 submissions worldwide.

In June, Yuen Yuen Ang, Assistant Professor of Political Science and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate, spoke at a panel on “What Should Tomorrow’s Aid Agencies Look Like?” Jointly organized by the Global Development Network (GDN) and Center for Global Development, the event featured Professor Ang as a winning author of the GDN Essay Competition on “The Future of Development Assistance,” sponsored by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The contest invited “original and innovative thinking on development assistance.” An international jury of development experts selected thirteen winners out of 1,470 submissions worldwide.

(more…)

Apr 4, 2016 | Conflict, International

Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Christian Davenport.

Department of Political Science Professor and Center for Political Studies faculty member Christian Davenport’s latest work examines transitional justice – judicial and non-judicial actions implemented by governments to deal with legacies of human rights abuses. These actions can typically include criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations, and various kinds of institutional reforms.

In Transitional Injustice: Subverting Justice in Transition and Postconflict Societies, published in the Journal of Human Rights, Davenport and Cyanne Loyle, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Indiana University, coin the term transitional injustice to describe governments that implement transitional justice without maintaining interest in truth, peace, or democracy. Instead, their intention is to promote denial and forgetting, violence, and legitimize authoritarianism.

The normative perspective of transitional justice assumes that legal processes following political conflict are implemented with the goal of reconciliation, peace, and democratization. It is assumed that “good” processes will lead to “good” outcomes. However, this assumption makes it possible for governments to hide behind transitional justice using similar legal institutions to advance detrimental aims. Davenport and Loyle argue that governments can use trials, truth commissions and amnesty without maintaining an interest in these goals, but rather to promote transitional injustice, i.e. denial, violence, and legitimizing state repression. Transitional injustice is particularly problematic for those interested in promoting justice processes because it reveals how institutions can be subverted for different purposes, often with international consent.

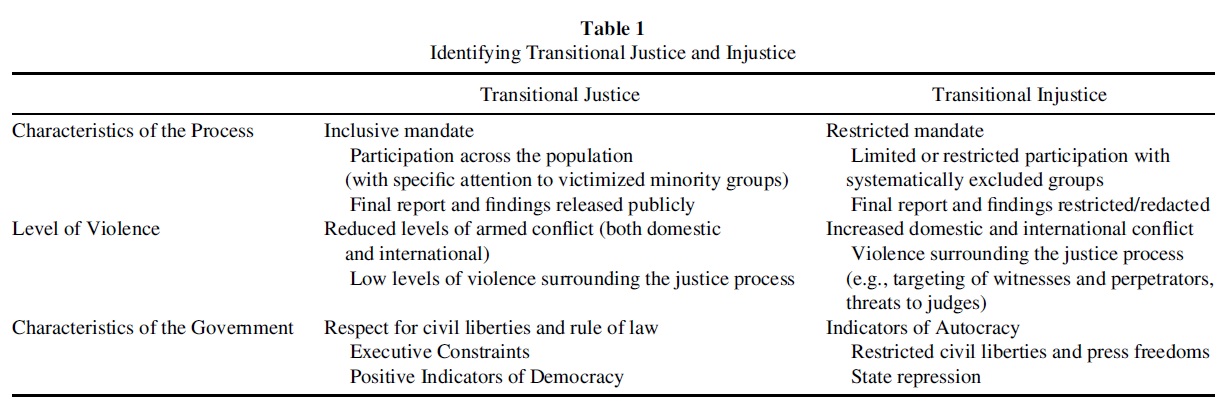

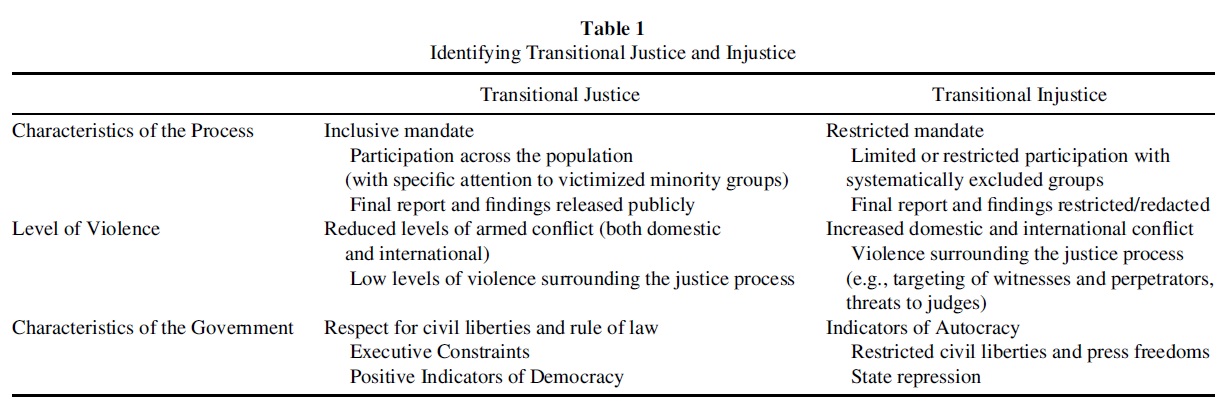

The article not only provides conceptual clarity on identifying differences but also provides indicators by which policy makers and scholars can determine if transitional injustice is taking place. In particular, policy makers can identify transitional injustice by relying on three key dimensions: (1) characteristics of the process, (2) levels of violence in the postconflict society, and (3) characteristics of the government (Table 1). These components allow government intentions and the potential for subversion of justice to be evaluated.

First, the degree of openness of the process is an indicator of the objectives of the government and the possibility for positive outcomes from the process. One could gauge the promotion or subversion of truth-telling by the degree to which distinct actors are integrated into the justice process, given an opportunity to participate, to draft, review and edit relevant decisions, as well as veto aspects of the process. Transitional justice should have a broad mandate incorporating all types of violations experienced during the conflict. Transitional injustice, however, reveals itself as a more closed process with a limited mandate and exclusion of certain individuals and groups.

The second indicator is the level of violence surrounding the process and the country. While violent events often linger in postconflict societies, the presence of transitional justice should lead to reduced levels of violence in the society overall. Transitional injustice however, is accompanied by violence internationally, domestically, and surrounding the process itself.

Third, characteristics of the government can be assessed by the level of democracy and the country’s present trajectory. Breaking from a past autocratic regime does not ensure that the new regime will be more democratic. Rather, the intentions of the regime should be assessed through institutional and behavioral indicators of democracy. The degree to which a justice process legitimates a democracy through open and frequent elections, diverse and representative political parties, and autonomous institutions is a valuable metric for understanding the general intent of those involved. Transitional justice should be accompanied by growing levels of democracy, while transitional injustice will accompany autocracy.

To more specifically illustrate how to identify transitional injustice, the article examines post-genocide Rwanda. On the surface, it appears that Rwanda’s approach to justice supports the normative aims of transitional justice. The Rwandan approach combines international, national, and local justice processes with the stated goals of truth and reconciliation, peace, and democracy. However, critics have called into question the ability of this justice package to accomplish those goals. Instead, it is being revealed that elements of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, national courts, and local justice processes have been used by the Rwandan government to promote denial, renewed violence, and the legitimization of an autocratic regime.

Regarding the openness of the process, the first dimension of transitional injustice, the space for justice in post-genocide Rwanda has been constricted through the support of targeted remembering, state-sanctioned scripted truths, and restricted access to justice. Instead of addressing all forms of conflict in Rwanda, the current justice package concentrates only on violence committed during the genocide. This strategy aims to direct attention to the successes of the government, namely ending the genocide, and away from its failures, mainly human rights violations and civilian massacres during the civil war and following the 1994 political transition.

Turning to the level of violence surrounding the process, far from reducing violence, the Rwandan approach to justice allows the government to increase domestic violence and international conflict. Violence has been a persistent component of the post-1994 Rwandan state, as in the aftermath of the genocide, a number of people were accused, tried and executed in a short period of time. By 2000, 348 people convicted of genocide crimes through the national courts were sentenced to death (Schabas, 2009), while the procedural fairness of many of those trials is questioned (Amnesty International, 2007). There has also been violence surrounding the justice processes themselves. In 2007 alone, the US State Department recorded 324 incidents of violence related to local justice processes, including killings of genocide survivors (US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 2008). While the government has officially denounced the violence, it has been reluctant or unable to stop it.

The final dimension of transitional injustice, characteristics of the government, provides an example of the Rwandan justice system working to consolidate an authoritarian regime and restrict political participation. The Rwandan government is a far cry from a functioning democracy. While elections have been held, their validity has been questioned and the lack of a viable opposition party has essentially made the country a single-party state (Reyntjens, 2004; Davenport, 2007). Freedom House (2007) has characterized elections as “marred by bias and intimidation which precluded any genuine challenge to the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)”.

Attempts to launch rival political parties have been met with intimidation and, in some instances, violence. The restriction of viable political alternatives to President Kagame’s RPF has limited the electoral power of individual citizens. In the 2010 presidential election, three opposition candidates were excluded from the ballot and Paul Kagame was reelected by 93% of the vote.

In conclusion, Rwanda claims to support domestic and international efforts to collect information about what happened, to communicate the findings, and capture and punish those who were involved in previous violent action. Through these efforts, the government has argued that it will advance truth and reconciliation, prevent violence and facilitate democratization. Unfortunately, by concealing political motivations in the obstruction of justice proceedings and engaging in violent activity, the Rwandan government is doing irreparable damage to the development of truth, reconciliation, rule-of-law, and democracy. In order to acknowledge and challenge this subversion, the international community must recognize the ability of justice institutions to be used for less democratic aims. This research therefore aims to provide skepticism regarding the goals associated with transitional justice as well as indicators to evaluate the potential subversion of relevant processes.

References:

Amnesty International. (2007). Truth, justice and reparation: Establishing an effective truth commission. AI Index: POL 30/009/2007. Available: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4678de4a2.html.

Davenport, Christian. (2007). State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Freedom House. (2007). Countries at a Crossroad: Rwanda. Available: https://freedomhouse.org/report/countries-crossroads/2007/rwanda.

Reyntjens, Filip. (2004). Rwanda, ten years on: From genocide to dictatorship. African Affairs,103, 177-210.

Schabas, William A. (2009). Post-genocide justice in Rwanda. In After Genocide: Transitional Justice, Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Reconciliation in Rwanda and Beyond, Phil Clark and Zachary D. Kaufman (eds.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Nov 3, 2015 | Conflict, Current Events, International, Uncategorized

Post developed by Yioryos Nardis in coordination with Yuri Zhukov.

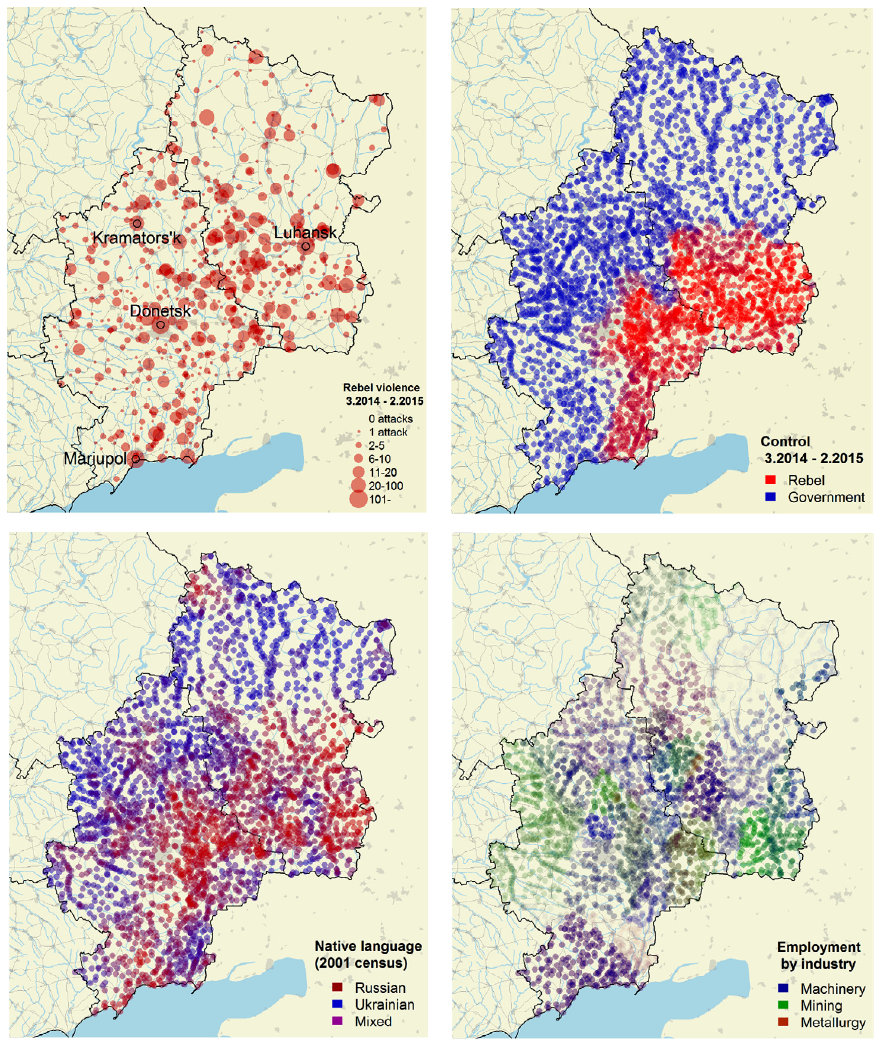

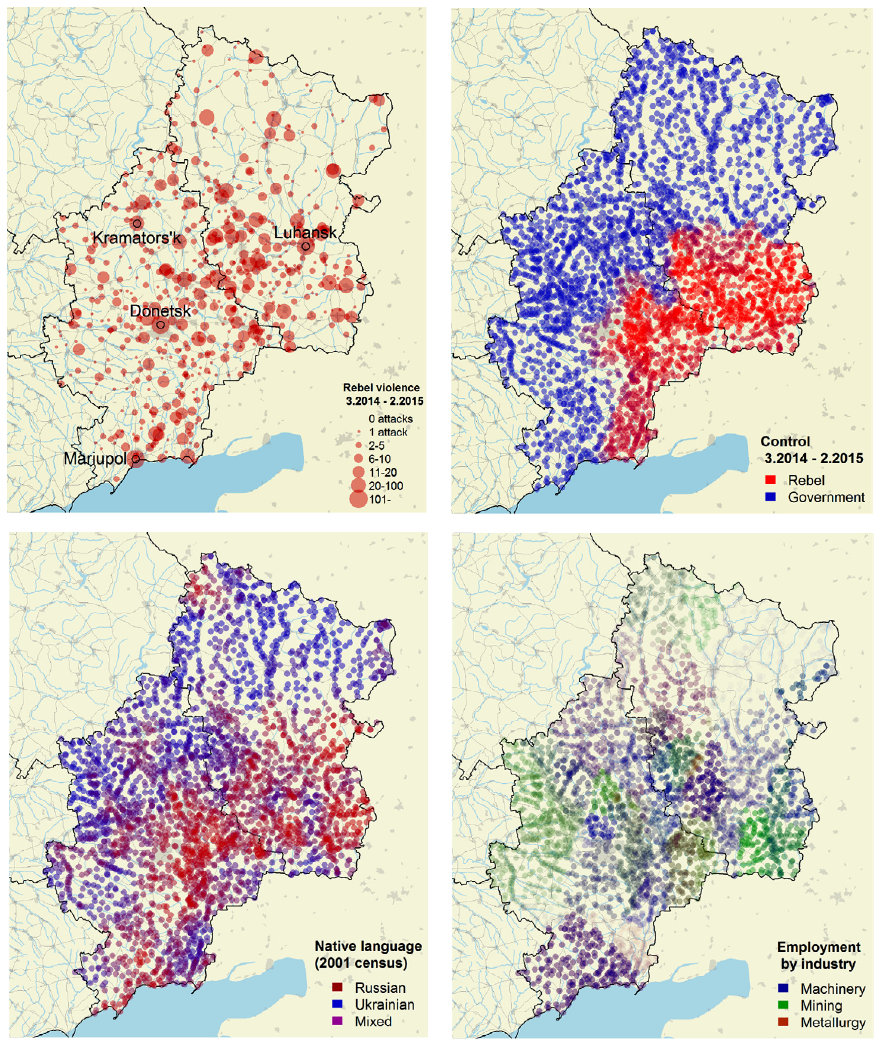

In March and April 2014, angry mobs and armed men stormed administrative buildings and police stations in eastern Ukraine. Waving Russian flags and condemning the post-revolutionary government in Kyiv as an illegal junta, the rebels proclaimed the establishment of ‘Peoples’ Republics’ of Donetsk and Luhansk, and organized a referendum on independence. Despite initial fears that the uprising might spread to other provinces, the rebellion remained surprisingly contained. While 61% of municipalities in Donetsk and Luhansk fell under rebel control during the first year of the conflict, just 20% experienced any rebel violence. What explains these local differences in rebellion across eastern Ukraine? Why have some towns remained under government control while others slipped away? Why might two municipalities in the same region experience different levels of separatist activity?

Yuri Zhukov

The latest research by Yuri Zhukov, faculty member in the Center for Political Studies and Assistant Professor of Political Science, uses new micro-level data on violence and economic activity in eastern Ukraine to examine these questions. In the paper “Trading hard hats for combat helmets: The economics of rebellion in eastern Ukraine” (forthcoming in the Journal of Comparative Economics) Zhukov evaluates two prominent explanations on the causes and dynamics of civil conflict in eastern Ukraine: ethnicity and economics.

Identity-based explanations expect conflict to be more likely and more intense in areas where ethnic groups are geographically concentrated. According to this view, the geographic concentration of an ethnolinguistic minority – in this case, Russians or Russian speaking Ukrainians – helps local rebels overcome collective action problems, while attracting an influx of fighters, weapons and economic aid from co-ethnics in neighboring states.

According to economic explanations, as real income from less risky legal activities declines relative to income from rebellious behavior, participation in the rebellion is expected to rise. This framework maintains that violence should be most pervasive in areas potentially harmed by trade openness with the EU, austerity and trade barriers with Russia.

Zhukov finds that local economic factors are much stronger predictors of rebel violence and territorial control than Russian ethnicity or language. Pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine are “pro-Russian” not because they speak Russian, but because their economic livelihood depends on trade with Russia.

The study uses new micro-level data on violence, ethnicity and economic activity in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, to understand how these two explanations are related to rebel violence and territorial control. The spatial units are 3037 municipalities (i.e. cities, towns, villages) in Donetsk and Luhansk provinces. For each municipality, Zhukov estimated the proportion of the local labor force employed in three industries: machine-building (which is heavily dependent on exports to Russia), metals (less dependent on Russia, and a potential beneficiary of increased trade with the European Union), and mining (vulnerable to International Monetary Fund-imposed austerity and cuts in state-subsidies). He also calculated the proportion of Russian speakers in each locality.

Rebel violence data are based on human-assisted machine coding of incident reports from multiple sources, including Ukrainian and Russian news agencies, government and rebel press releases, daily ‘conflict maps’ released by both sides, and social media news feeds. This yielded 10,567 unique violent events in the Donbas, at the municipality level, recorded between the departure of President Viktor Yanukovych in February 2014 and the second Minsk ceasefire agreement of February 2015. To determine territorial control, particularly whether a populated place was under rebel or government control on a given day, Zhukov used three sources: official daily situation maps publicly released by Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council (RNBO), daily maps assembled by the pro-rebel bloggers ‘dragon_first_1’ and ‘kot_ivanov’, and Facebook posts on rebel checkpoint location.

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).

To evaluate the relative explanatory power of ethnic and economic explanations of violence in the Donbas, the study uses Bayesian Model Averaging. It finds that a municipality’s prewar employment mix is a better predictor of rebel activity than local ethnolinguistic composition. Municipalities more exposed to trade shocks with Russia experienced a higher intensity of rebel violence throughout the conflict. Municipalities where machine-building represented a small share of local employment (2%, the lowest in the data) were 38% less likely to experience violence than municipalities where the industry was more dominant — and the local population more vulnerable to trade disruptions with Russia. Such localities also fell under rebel control earlier – and took longer for the government to liberate – than municipalities where the labor force was less dependent on exports to Russia. On any given day, a municipality with higher-than-average employment in the beleaguered machine-building industry (26%) was about twice as likely to fall under rebel control as a municipality with below-average employment in the industry (4%).

By contrast, ethnicity and language had no discernible impact on rebel violence. Municipalities with large Russian-speaking populations were more likely to fall under rebel control, but only where economic dependence on Russia was relatively low. In other words, ethnicity only had an effect where economic incentives for rebellion were weak.

The seemingly rational economic self-interest at the heart of the conflict stands in sharp contrast with the staggering costs of war. In the twelve months since armed men began storming government buildings in the Donbas, over 6000 people have lost their lives, and over a million have been displaced. Regional industrial production fell by 49.9% in 2014, with machinery exports to Russia down by 82%.Suffering heavy damage from shelling, many factories have closed. With airports destroyed, railroad links severed and roads heavily mined, a previously export-oriented economy has found itself isolated from the outside world.

References:

2001 Ukrainian Census (State Committee on Statistics of Ukraine, 2001).

Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis database (Bureau van Dijk Electronic Publishing, 2015).

Segodnya, 2015. Ekonomika donetskoy oblasti v upadke iz-za voyny – gubernator kikhtenko. [Donetsk region’s economy in stagnation because of the war – Governor Kikhtenko]. Segodnya.

Stasenko, M., 2014. Novaya ekonomika ukrainy budet stroit’sya bez rossii i donbassa [Ukraine’s new economy will be built without Russia or the Donbas]. Delo.ua.