Oct 7, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, International, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ugo Troiano.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

Around the globe, the average maternity leave is 118 days, but with a lot of variation. Maternity leave periods range from 45 days in Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates to 480 days in Sweden. Why the difference? And, moreover, does the variation relate to gender discrimination?

Assistant Professor of Economics and Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate Ugo Troiano, along with Yehonatan Givati of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Law School, investigated these questions and published their results in an article in The Journal of Law and Economics.

Their core theory is simple: maternity leave is costly to employers, so when the government mandates long periods of maternity leave, women may be discriminated against and receive lower wages as a result. However, places with a low tolerance for pay gaps won’t let that happen, and the incidence of this policy ends up being shared across genders. As a consequence, it becomes more economically “optimal” to enact longer mandatory maternity leaves in societies that are not discriminatory toward women. This theory is consistent with the empirical evidence.

The authors show that maternity leave is indeed shorter in societies where survey respondents think that men should receive preferential treatment in the workplace. The authors measure this attitude through a World Values Study question that asks level of agreement with, “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” Aggregated to the national level and combined with data on the length of maternity leaves, they find the two are related.

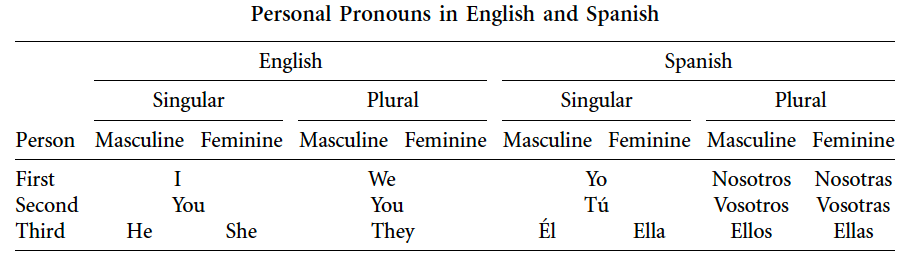

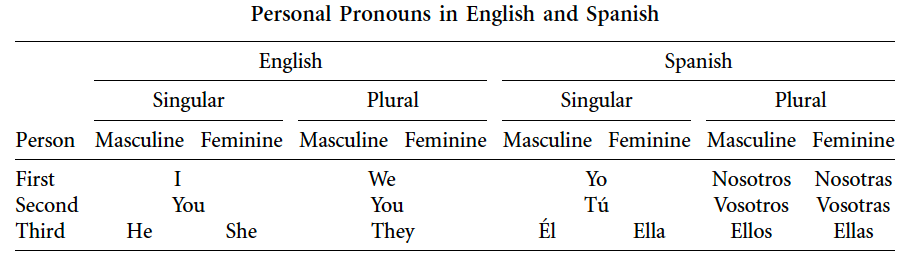

However, that evidence alone does not allow us to conclude that culture is causing a longer leave, because it’s possible that causation goes in the opposite direction: a longer leave is causing more tolerant attitudes toward women. In order to alleviate this concern, Givati and Troiano looked at a proxy from attitudes less likely to change because of maternity leave: language. Specifically, they developed a measure from recent research in psychology and linguistics known as linguistic relativity suggesting that language shapes thought. Following from this, they analyzed the number of gender-differentiated pronouns across languages to see if this corresponded to tolerance of gender discrimination. For example, English uses one gender-differentiated pronoun associated with gender and the number of people referenced, while Spanish uses three (see the table below). In all, Troiano and Givati tallied the number of gender-differentiated pronouns in 33 languages using grammar books, and they looked to see whether the number of pronouns was negatively correlated with gender tolerant attitudes.

The authors indeed find a connection, with more gendered pronouns correlated with greater tolerance of gender discrimination as measured by the World Values Survey question. Next, the authors estimated a regression model, with length of maternity leave as the dependent variable and number of gendered pronouns as the independent variable. Troiano and Givati find that the more gendered pronouns, the shorter the maternity leave. Or, on the flip side, the fewer gendered pronouns, the longer the maternity leave.

Troiano concludes, “This project is an example of how concepts from different social sciences can be used to answer specific policy questions. To understand the factors that affect the variation of maternity leave across countries we integrated economic concepts (incidence of a policy), sociological ones (measuring attitudes from survey) and linguistic ones.”

Sep 4, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, International, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Anne Pitcher.

Housing construction in Angola’s capital of Luanda; Photo credit: Anne Pitcher

Research and news about Africa tend to focus on failed states, poverty, and corruption. While these themes ring true for some African countries, others have witnessed the expansion of urban areas, rising demand for consumer goods, and the growth of a middle class. Angola has “done it all.” Angola has experienced conflict but has now transitioned to peace. It has high rates of poverty but also has an emerging middle class.

Located in Southern Africa, with the Atlantic Ocean to the West, Democratic Republic of the Congo to the North, Zambia to the East, and Namibia to the South, Angola achieved independence from Portugal in 1975 only to become embroiled in a decades long civil war. Further, as an ally of Russia and Cuba, Angola remained isolated from the Western world for the duration of the Cold War.

Due to political instability and isolation, Angola’s nearly 20,000,000 citizens have been largely ignored in rigorous analysis. In fact, Angola is one of the least researched places in the world. Although there are several reputable research institutions based in Angola, most major surveys of the continent, like those conducted by the Afrobarometer, World Bank, or the African Development Bank, do not include Angola. Meanwhile, the results of the Angolan government’s own first census data will not be released for several more years.

Owing to her research experience in Mozambique, another African country formerly colonized by the Portuguese, Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate Anne Pitcher decided to include Angola in her research beginning several years ago. Pitcher, also a Professor of African Studies and Political Science and Coordinator of the African Social Research Initiative, is interested in understanding patterns of goods distribution in Angola following the end of the civil war in 2002.

In particular, she wants to be able to explain why the government of this oil producing country had made a commitment to build a million homes for the urban poor and the middle class; how such an ambitious commitment is actually being realized in a country where revenues from oil completely dominate the Gross Domestic Product; and who is really benefiting from construction and sales in a place with a tightly knit elite and huge disparities in wealth.

To this end, Pitcher has teamed up with Angolan scholar Sylvia Croese and Allan Cain, the director of Development Workshop (a widely respected organization based in Luanda, Angola, and one of the few to attempt systematic studies of land, property rights, and patterns of urbanization in Angola). The researchers are currently conducting 200 tablet-based surveys of housing finance and satisfaction in Kilamba, a new city consisting of 20,000 units located on the outskirts of the capital city of Luanda. Financed by a 3.5 billion USD credit line from the Chinese government to the government of Angola, Kilamba is being built by the Chinese International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC) to house Angola’s growing middle class. Housing purchases are partly subsidized by the government and when fully occupied, Kilamba will house 150,000 people.

Conducting research in Angola has proven both easier and more difficult than expected. Pitcher anticipated that survey respondents might be reluctant to participate since Angola does not have a history of conducting public opinion surveys. Instead, she has found participants excited to voice their opinions. Pitcher attributes this eagerness to the limited avenues for self-expression in the relatively closed country. The survey’s timing has also tapped into the gradual opening of the society, as evidenced by support for the survey from the country’s Ministry of Urbanism and Housing. Yet the team has faced some obstacles. Building the participant pool has proven challenging, as the country lacks confirmed population data; exact occupancy rates in Kilamba are unknown; and there is very little existing background data from which to build hypotheses about how residents earn their incomes or finance purchases.

But so far, the survey team has persevered. Data collection ends this month, and the product will serve as some of the most comprehensive data of its sort ever collected in Angola (in addition to the still unreleased census). Beyond a number of questions drawn from Afrobarometer public opinion surveys conducted across the rest of Africa, the survey includes questions that have never been systematically asked about housing finance, satisfaction with housing, education, and commute times. It also measures public opinion on issues like the distribution of wealth, poverty, taxes, and unemployment.

A completed Kilamba housing development; Photo credit: Anne Pitcher

Pitcher believes that understanding real estate finance and the opinions of new middle class homeowners will offer valuable insights into the quickly evolving politics of the country. Why? The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) party has ruled the country since the nation’s independence in 1975. With the recent shift from a Marxist-Leninist one party system to multi-party politics, the MPLA wants to maintain power. Constructing houses is part of this effort. Among other models, the MPLA modeled this venture on Margaret Thatcher’s campaign to offer housing to Britain’s council residents in the 1980s. Thatcher hoped that providing housing would lead to more conservative and more loyal citizens. The MPLA may likewise hope that creating homeowners will create stability in a country marred by decades of war. Currently, many young people in Angola express great discontent, particularly with respect to a lack of housing. The study by Pitcher, Croese, and Cain will offer a better understanding of whether that discontent is being addressed or modified.

With data collection nearly complete, Pitcher is very excited to dive into the data. In the near future, the research team hopes to expand the scope of the survey to include additional types of urban housing such as social housing that is offered for free to those with minimal resources; self constructed housing built by individuals themselves; and cooperative private housing. Because the government is involved to varying degrees with each of these types, understanding the differences may not only shed light on politics and economics, but also offer insight on best practices with respect to housing finance and citizen satisfaction in developing, post-war countries.

Aug 28, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Nicholas Valentino.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “The Attitudinal Structure and Political Consequences of Group Empathy,” was a part of panel “32-8. Race and Political Psychology” on Thursday August 28th, 2014.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

Group empathy is the ability to see through the eyes of another, to take their perspective and experience their emotions. The ability to experience empathy is adaptive in families and friendships. But how can we best measure empathy? And how do life experiences condition one’s ability to feel empathy?

Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor and Professor of Political Science Nicholas Valentino, along with Cigdem Sirin-Villalobos and Jose Villalobos, both of the University of Texas, El Paso, seek to answer these questions. To do so, they conducted a survey with Knowledge Networks. The survey included 1,799 participants, of which 633 were White, 614 Black, and 552 Latino/a.

The authors contend that empathy is not just the ability to take another’s perspective, but the motivation to do so. To this end, they asked 14 questions to create a “Group Empathy Index” (GEI). Examples of the items included statements such as “The misfortunes of other racial or ethnic groups do not usually disturb me a great deal” and “I am often quite touched by things that I see happen to people due to their race or ethnicity.” They also asked about empathy toward specific groups. Analysis showed the new scale to be both reliable and valid.

In addition to better measuring empathy, the authors wanted to understand the role of related personal traits. They found that race, gender, and education condition empathy. In particular, being a minority or a woman, and having more education, are related to higher empathy. Further, personally experiencing unfair treatment by law enforcement also related to higher empathy. Minorities reported more unjust treatment by law enforcement, which might underlie the different levels of empathy by race.

The survey also included questions to gauge political implications of empathy. The study found that those who display higher empathy showed greater support for immigration, valued civil liberties more than societal security, and were more likely to volunteer and attend rallies. The authors concluded that, “Such variations in empathy felt toward social groups other than one’s own may thus have powerful political consequences.”

Aug 19, 2014 | International, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Arun Agrawal.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate and Professor in the School of Natural Resources and the Environment (SNRE) Arun Agrawal studies environmental policy.

Professor Agrawal and the International Forestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) program he coordinates just received a grant of 1.9 million pounds (about $3.2 million) over four years from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID).

Agrawal’s proposed research seeks to improve measurement of the outcomes of forest investments. Forest investments try to minimize the negative impacts of forest-related changes: by influencing land use, agriculture, institutions, migration, and commodity production. Substantial forest investments have occurred in the past few years, driven in part by concerns about climate change and the role of land changes in contributing to global emissions. Assessing the impacts of these programs, therefore, and improving their effectiveness is urgent. As Agrawal explains, “there is a lack of rigorous and generalizable empirical analyses of the effectiveness of past forest investments. Existing knowledge is often anecdotal, based on non-systematically selected indicators, usually supported only by information from a small number of unrepresentative cases, and through studies without rigorous counterfactual analysis.”

With this grant, Agrawal and his collaborators will methodically study the impact of forest investments with empirical data and quantitative analysis. In particular, Agrawal will seek answers to three key questions:

- What is the impact of specific types of forest interventions across different policy and governance contexts?

- Where and under what conditions do forest interventions deliver positive impacts?

- Which forest interventions have resulted in more positive impacts and why?

The research will focus on Brazil, Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, and Nepal, using these countries to generate rigorous, valid, reliable, and generalizable findings.

Jul 17, 2014 | International, Social Policy

Post by Rosemary Sarri.

This post was written by Center for Political Studies, School of Social Work and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri, after her visit to the Philippines in the spring of 2014.

A fishing project in the Philippines

As covered in an earlier post, the population of the Philippines has skyrocketed from just 26,272,000 people in 1960 to 98,734,000 people in 2014, a growth rate of 254%. The limited size and resources of the Philippines limits employment opportunities for the adult population. Even professionals educated as teachers, nurses, physicians, and other health workers struggle to find work. Today, nearly 50% of the adult population is employed overseas in the Middle East, several Asian countries, and the United States. Young parents often leave their children with extended family and work overseas for many years.

Fishing is an important occupation in the Philippines for men and women. I visited a cooperative fishing community in Rizal Province and was impressed by the active participation of local community people in developing the fishing industry in Laguna Lake, home to fishing ponds for developing and testing fish for a variety of purposes. Several in this community were active in advancing legislation to promote the industry in a variety of ways.

The response to the weed menace of water lilies showcases the creativity and ingenuity of this community. They now cut the water lilies, dry them, and make them into a variety of projects such as mats for sleeping, slippers, and bags. They also have promoted the planting of mangroves along the ocean coasts of the Philippines to control water damage from typhoons.

A mat woven with dried water lilies

The fisher people’s association shows one avenue for securing better employment for the Philippines’ growing population. Another activity of the fisher people is the promotion of the planting mangroves in many the shoreline communities. These mangroves have been shown to be effective in reducing the water damage that these communities suffer because of typhoons.

Jun 11, 2014 | International, Social Policy

Post by Rosemary Sarri.

This post was written by Center for Political Studies, School of Social Work and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri, after her visit to the Philippines in the spring of 2014.

Manila slum from a car window

The island country of the Philippines is the 12th most populous country in the world with a growth rate of 1.89% per year. The population skyrocketed from just 26,272,000 people in 1960 to 98,734,000 people in 2014, a growth rate of 254%. Tremendous cost has accompanied this explosive growth. Most of the population live below the poverty line and reside in urban or metropolitan areas which are extremely crowded. The slums of Manila have become almost inhuman places in which to reside. Because the land prevents the creation of a subway system, the country primarily relies on motor vehicles for transportation, creating terrible pollution that tripled in recent years.

Recently, some local non-profit organizations have organized efforts to foster community development. One of these organizations is Gawad Kalinga, established by a small group of benefactors to work with the people of the slums to provide them with land, food, and housing.

I visited one of their projects in Cavite Province, located a short distance from Manila. They emphasize the restoration of community empowerment and training for gainful employment and active citizenship. Gawad Kalinga gives priority to dismantling the pattern of despair and abandonment that overwhelms the lives of the very impoverished.

Gawad Kalinga believes moving people out of the slums is essential to eradicating poverty. The project that I visited in Cavite provides brightly painted single or duplex housing for about 45 families with a community center, health center, an informal education center and a grocery store. The residents learn to care for their own facilities. Overall the community survey indicated that they received good health care and education for their children. Employment of the men in nearby communities is strongly encouraged, but many, especially women, wanted more assistance in obtaining employment.

Buildings of Gawad Kalinga

While Gawad Kalinga is making strides in the right direction, birth control and family planning are issues that probably deserve more attention. Families in the community have a median of three children. And over-population is a country-wide problem. The strong influence of the Catholic Church since its colonization by Spain resulted in strong opposition to most methods of contraception or birth control. In 2012, this influence started to wane as the government began to address over-population with the passage of the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act. Yet, a recent community survey by the Philippine School of Social Work at The Philippine Women’s University indicates that 69% of Filipinos rely on “natural methods” of family planning or abstinence. Despite a national campaign for vasectomy, few Filipinos opted for the procedure.

Gawad Kalinga embodies the Philippines’ overpopulation problems, both as a solution to the inhuman living conditions of Manila’s slums, a partial answer to unemployment woes, and an underscoring of the country’s population problem.

Sarri with some of the women residents of Gawad Kalinga