May 8, 2014 | ANES, Current Events, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ashley Jardina.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

This month, Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy made headlines. What started as a battle against the U.S. Federal Government for his cattle and land turned into daily press conferences. As part of the Sovereign Movement, Bundy used the attention to propagate an anti-government agenda and racist ideas. Across the country at Princeton University, freshman Tal Fortgang also made headlines with his essay, “Checking my Privilege.” His championing of white privilege garnered backlash in the press. What do Bundy and Fortgang have in common? Both demonstrate reactions to a perceived status threat to whites.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) affiliate and Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Michigan Ashley Jardina studies white identification. In particular, she argues that threats to dominant status make racial identity salient. Does this in turn influence support for political policies that could eliminate such status threats?

To answer this question, Jardina analyzed data from the American National Election Studies (ANES). Especially relevant is a measure of racial identity importance available for the first time in the 2012 ANES. This measure let Jardina gauge the extent to which white Americans feel that being white is important to their identity. She looks at whether this white identity relates attitudes toward policies (e.g., immigration) and candidates (e.g., Barack Obama) that exacerbate threats to white dominance. Immigration especially threatens whites’ dominance, because it drives demographic changes whereby whites are being displaced as the majority racial group in the nation. Likewise, as the country’s first African American president, Obama also represents a status threat.

Previous work has argued that out-group attitudes, either toward Hispanics or blacks, primarily drive whites’ attitudes toward immigration policy and support for Obama. But Jardina constructs models to explicitly test the relationship between in-group / out-group feelings. She finds in-group identity to be a more powerful and consistent predictor of restrictive immigration policies than out-group attitudes, including evaluations of Hispanics. Furthermore, whites who identified with their racial group were significantly less likely to vote for Obama, even after controlling for racial prejudice or resentment. Her results are replicated using two other datasets. Jardina concludes, “These results lend support for the notion that, in some important cases, a desire to protect the in-group, rather than dislike for the out-group, primarily drives opinion.”

Ashley Jardina will join Duke University in the fall as an Assistant Professor of Political Science.

Feb 13, 2014 | Michigan, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Rosemary Sarri.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

400,000 youth are placed out of home in residential treatment institutions in the United States because they were abused or neglected their family. Just 2% of these youth placed out of home in institutions will run away each year, compared to the annual runaway rate of of 6-8% for American youth overall. But the ramifications for the institutionalized runaway youth are grave, including homelessness, poverty, substance abuse, exploitation, and crime.

Center for Political Studies (CPS), School of Social Work, and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri studies the impact of social policy on children. A forthcoming paper with her colleagues Joseph P. Ryan and Elizabeth Stoffregen, who are also of the Institute for Social Research (ISR), considers the serious risks for these youth running away from the child welfare system. The article asks: Does running away from these institutional placements pose an increased risk of future involvement with the juvenile and/or adult justice systems?

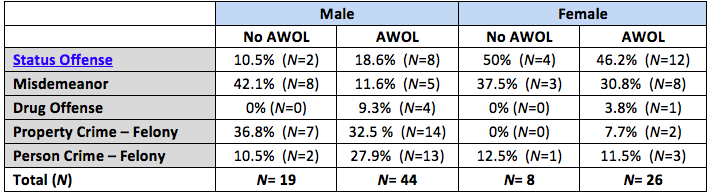

Focusing on Wayne County, Michigan, home of the city of Detroit, the study includes 371 children aged twelve or older from the child welfare system that ran away at least once in 2003, matched against similar children in the system that did not run away. The data trace involvement of the youth from the two groups in the justice system over eight years.

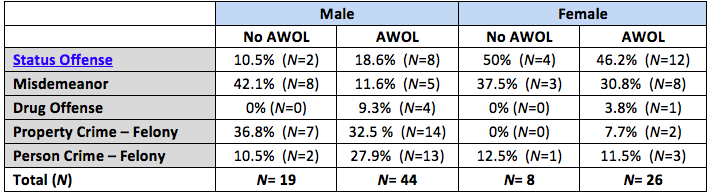

Sarri finds that running away is indeed associated with negative outcomes. Overall, youth who run away from institutional placements have a 40% chance of ending up in the adult justice system. For males, this increases to 71.5%. The table below breaks down the most serious offenses by status and gender for the youth who ran away from institutions. Indeed, youth who run away from institutions commit more serious crimes, especially males.

Most Serious Juvenile Justice Offense by Gender and Runaway Status (the term “AWOL” identifies youth who ran away from institutions)

Given these staggering results, what can be done? Most of the youth are neglected, often with deep issues relating to substance abuse, mental health, homelessness, and crime. As such, Sarri calls for a positive, restorative approach that sets goals and offers resources to help youth achieve them. The Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform have developed an inter-agency collaborative proposal to provide more effective treatment for these “crossover” youth who are at high risk when they drift to the justice system.

Feb 3, 2014 | ANES, Conflict, Current Events, National, Social Policy

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Darrell Donakowski.

Source: Thinkstock

On September 16, 2013, a former reservist killed 12 people in a Washington, D.C. Navy Yard. This latest high profile mass American shooting prompted President Obama to urge another push for stronger gun control. Obama first marked the issue as a national priority after a gunman shot and killed 20 first graders and six educators in a Newtown, Connecticut elementary school in December 2013. Obama promised to do everything in his power to prevent another such tragedy. In a Newtown vigil, and referencing the Aurora, Colorado movie theater shooting of the previous summer that killed 12 and injured 70, Obama declared enough.

Obama’s post-Newtown proposals included tougher background checks to purchase arms and the ban of military-style assault weapons used in several high profile mass shooting. But the package stalled in Congress. After the Navy Yard shooting, Obama urged the electorate not to accept mass shootings as a new normal, instead to demand common sense gun laws.

How do the American people feel about gun control?

For 65 years, the American National Election Studies (ANES) have interviewed a representative sample of voting age Americans on a variety of topics, including but not limited to voting and turnout, public policy support, societal values, and demographics. As ANES describes, the resulting data “inform the nation about itself.” Data from the 2012 survey were released at the end of June 2013.

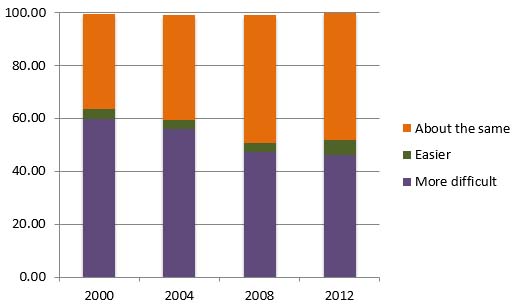

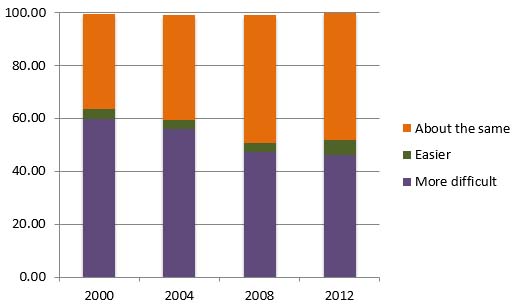

One question in particular from the ANES sheds light on national attitudes toward gun control. The question was asked in 2000, 2004, 2008, and 2012, allowing us to trace responses over time. The graph below displays these trends (leaving out the small fractions who did not know or refused to answer).

Do you think the federal government should make it more difficult for people to buy a gun than it is now, make it easier for people to buy a gun, or keep these rules about the same as they are now?

As we can see, the proportion of the public supporting tougher regulation is shrinking over the time period, while satisfaction with current regulations increased. Yet, support for tougher gun laws is the most popular choice in all included years. It is important to note that these data were collected before Aurora, Newtown, and the Navy Yard shootings. The 2016 ANES study will no doubt add more insight into this contentious, important issue.

Nov 14, 2013 | ANES, Michigan, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In June of this year, the Supreme Court of the United States maintained the legality of affirmative action programs at American colleges and universities – for now. The Supreme Court’s seven-to-one decision pushes American colleges and universities to prove the utility of affirmative action programs. The court declined to rule specifically on a case regarding the University of Texas at Austin’s affirmative action policy. This week, the UT Austin case was debated before a federal court.

How does the American public feel about affirmative action, and has their support or opposition changed over time? The American National Election Studies (ANES) can be used to examine such trends. For 65 years, the ANES has interviewed a representative sample of voting age Americans on a variety of topics, including but not limited to voting and turnout, public policy support, societal values, and demographics. As ANES describes, the resulting data “inform the nation about itself.”

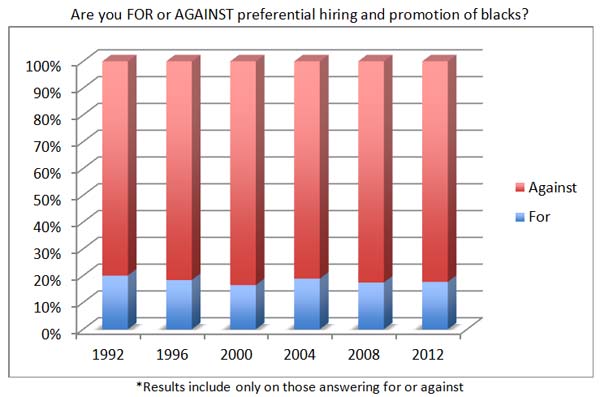

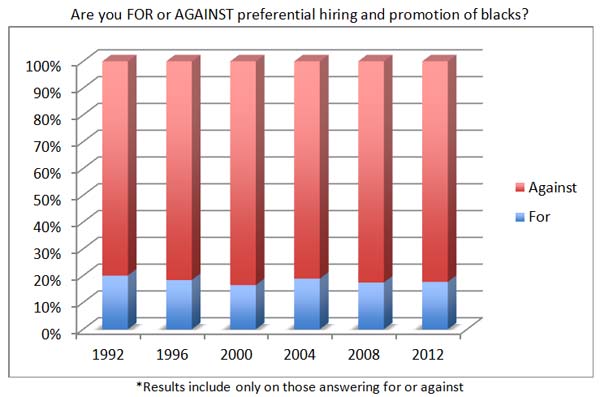

There are many ways to measure levels of support or opposition for affirmative action. Since 1992, ANES has asked the American voting age public whether it is “for or against” one type of affirmative action: preferential hiring and promotion of blacks. As the graph below illustrates, public opposition in the United States for this type of affirmative action appears both dominant and stable over the time period 1992-2012.

In 2012, ANES also asked a question about support or opposition for the use of quotas to admit black students to colleges and universities. The results were similar, with 77% of respondents opposing such a program and 23% of respondents being in support.

The latest Supreme Court ruling comes on the heels of a 2003 Supreme Court decision regarding the University of Michigan‘s use of affirmative action in its decision-making process for admitting students. The Court upheld the use of affirmative action by the University’s law school but negated the use of affirmative action in its undergraduate admissions. In 2006, voters from the state of Michigan voted in support of a ballot referendum, Proposition 2, which made affirmative action illegal in the state. Then in November of 2012, the state of Michigan’s 6th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Proposition 2. Last month, the constitutionality of Proposition 2 went before the Supreme Court of the United States.

The latest court proceedings suggest that the future of affirmative action remains unclear, but results from the ANES suggest that public opposition to affirmative action remains stable. Yet, no single question or two can encapsulate feelings toward an issue as complex as this one.

Oct 31, 2013 | Michigan, National, Social Policy

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Rosemary Sarri

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In June of 2013, Sesame Street debuted its first character with a parent in prison. The Sesame Street website now features a page of video clips and guides to help children facing this situation. But how likely is it a child will see his or her parent go behind bars?

The U.S. has a high rate of incarceration, about 760 per 100,000. The rates are higher than peer countries – five times the rate of Britain, and eight times the rate of Germany. But are the rates even higher for families with criminal pasts?

Center for Political Studies (CPS), School of Social Work, and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri studies social policy, with an emphasis on children in the justice system. In a paper just published with Irene Ng and Elizabeth Stoffregen in the Journal of Poverty, Sarri considers the intergenerational nature of incarceration.

The study grew from a larger effort to understand preparation of youth returning from detention to the community. Data analysis revealed high levels of parental imprisonment among the youth in the sample. So the researchers considered the issue in more depth.

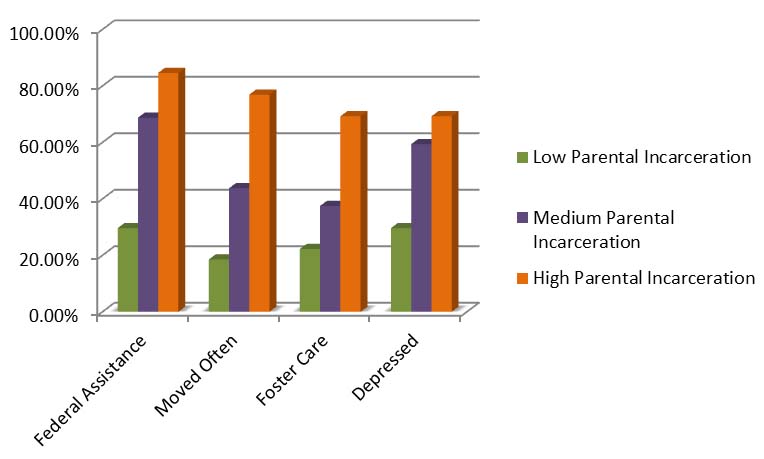

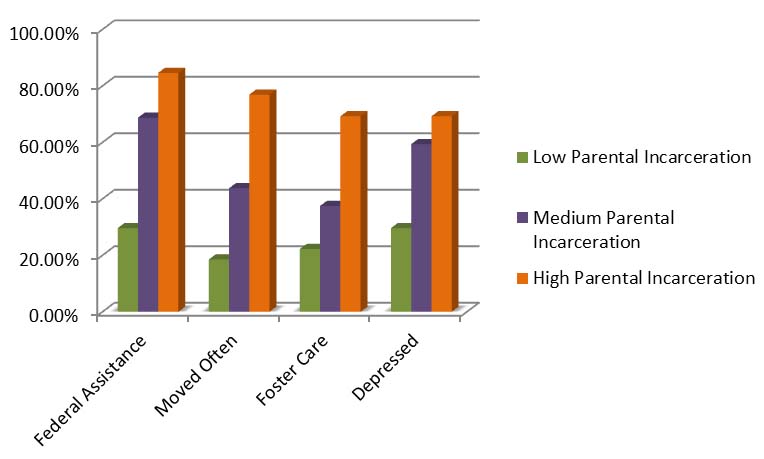

The researchers broke their participants into three groups: low, medium, and high levels of parental incarceration. Then they performed a cluster analysis to determine if these three groups varied along different factors.

The results indicate that higher levels of parental incarceration correspond to negative life events, parental substance abuse, receiving federal assistant, placement in foster care, neighborhood quality and instability, stigma, and negative youth outcomes. The graph below displays four of these associations by level of parental incarceration.

So having a parent in prison not only increases the risk of a child facing juvenile lock up, but is also associated with other negative experiences. The troubles appear to perpetuate along family trees. A staggering 53% of the juvenile offenders in the study have children themselves. Further, most of the male participants expected little future contact with their children.

It would be easy to be pessimistic given these results, but the results highlight a situation that needs to be addressed. In response, Sarri calls for a re-examination of imprisoning parents. She argues that these families and society at large could benefit from community programs that support families. Such community programs demonstrate long-term positive effects for both parents and children. When used for non-violent offenses, like drug abuse, such community programs protect public safety while potentially redirecting the growth of ill-fated family trees. Sarri also suggests parenting training, substance abuse and mental health treatment, workforce development, and community organization to relieve disorganization. These preventative services could help redirect families before there’s a problem.

Aug 22, 2013 | Innovative Methodology, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Nicholas Valentino

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Since the attacks of September 11, 2001, airport security has become a grave and expensive endeavor, projected to cost $45 billion by 2018. News stories about airport security scares or the ridiculousness of airport security scares proliferate. Other stories concern the efficacy of racial profiling, particularly of Arab passengers. A new Transportation Security Administration (TSA) program called SPOT – Screening of Passengers by Observation Technique – targets suspicious behavior in security lines with in-depth questioning. This program alone has cost $878 million. And SPOT faces criticisms for propagating racial profiling.

Forthcoming research by Center for Political Studies researcher Nicholas Valentino, along with colleagues Cigdem Sirin and Jose Villalobos from the University of Texas El Paso, explore the factors that explain support for racial profiling. In particular these scholars wondered whether different racial groups, with their different experiences with discrimination, react distinctly to security policies that involve profiling.

Valentino and colleagues investigated this question in an experiment. The sample focused on three racial groups and included 221 whites, 193 blacks, and 207 Latinos. All participants read a vignette:

Recently, a passenger was flying from New York to Chicago when he was pulled out of a security line, searched, and questioned. The passenger was talking on his cell phone while waiting in line to board his flight. One of the airport security officers standing nearby said that he heard the passenger say, “It’s a go!” which qualifies as suspicious behavior according to the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) guidelines. In response, the airport security officer took the passenger aside for further screening. The passenger, however, claims that when it was his turn to board the plane, he had told the person on the phone, “I’ve got to go!” and hung up. Amid the controversy, the airport security officer said that he had a reasonable cause to search and question the passenger. The passenger, on the other hand, said that the additional screening was unwarranted.

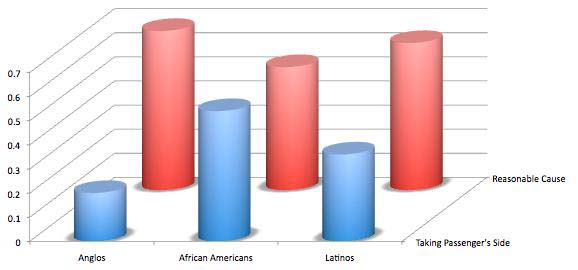

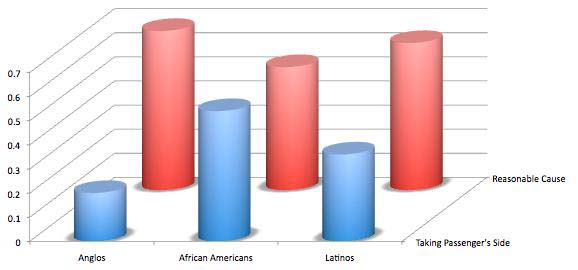

The picture presented alongside the text varied, with participants randomized to see a suspect from one of four racial groups: black, white, Latino, or Arab. Pictures were pretested to ensure equality on all dimensions except ethnic identity. After reading the story, participants answered several questions, including, “Who are you more likely to agree with in this case—the airport security officer or the passenger?” and “What do you think about the response by the airport security officer—do you think he had a reasonable cause to search and question the passenger?”

The graph below displays the results for the Arab passenger scenario. Compared to whites, blacks and Latinos showed less support for extra airport security measures targeting an Arab passenger. Further, the likelihood of siding with the Arab passenger is about 36 percent higher for black respondents and about 26 percent higher for Latino respondents.

Yet, blacks and Latinos perceive themselves to be at higher risk of personal threat from terrorism. Valentino and colleagues suggest this pattern is consistent with Group Empathy Theory, which holds that empathy for one group by another, even when the two are in competition for the same resources, mitigates support for harsh security tactics.

Lawmakers and TSA programs should keep in mind, as Valentino states, “These results demonstrate that anti-Arab sentiment is not distributed uniformly throughout society, and support our theory that the power of existential threats on tolerance is moderated by group empathy.”