Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Rosemary Sarri

In June of 2013, Sesame Street debuted its first character with a parent in prison. The Sesame Street website now features a page of video clips and guides to help children facing this situation. But how likely is it a child will see his or her parent go behind bars?

The U.S. has a high rate of incarceration, about 760 per 100,000. The rates are higher than peer countries – five times the rate of Britain, and eight times the rate of Germany. But are the rates even higher for families with criminal pasts?

Center for Political Studies (CPS), School of Social Work, and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri studies social policy, with an emphasis on children in the justice system. In a paper just published with Irene Ng and Elizabeth Stoffregen in the Journal of Poverty, Sarri considers the intergenerational nature of incarceration.

The study grew from a larger effort to understand preparation of youth returning from detention to the community. Data analysis revealed high levels of parental imprisonment among the youth in the sample. So the researchers considered the issue in more depth.

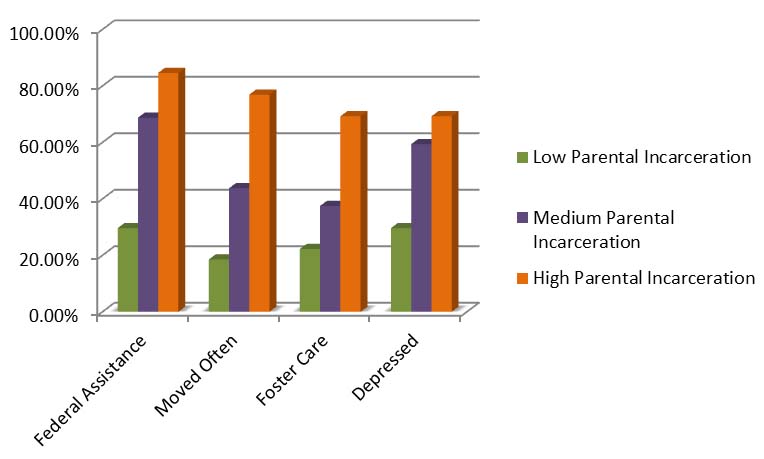

The researchers broke their participants into three groups: low, medium, and high levels of parental incarceration. Then they performed a cluster analysis to determine if these three groups varied along different factors.

The results indicate that higher levels of parental incarceration correspond to negative life events, parental substance abuse, receiving federal assistant, placement in foster care, neighborhood quality and instability, stigma, and negative youth outcomes. The graph below displays four of these associations by level of parental incarceration.

So having a parent in prison not only increases the risk of a child facing juvenile lock up, but is also associated with other negative experiences. The troubles appear to perpetuate along family trees. A staggering 53% of the juvenile offenders in the study have children themselves. Further, most of the male participants expected little future contact with their children.

It would be easy to be pessimistic given these results, but the results highlight a situation that needs to be addressed. In response, Sarri calls for a re-examination of imprisoning parents. She argues that these families and society at large could benefit from community programs that support families. Such community programs demonstrate long-term positive effects for both parents and children. When used for non-violent offenses, like drug abuse, such community programs protect public safety while potentially redirecting the growth of ill-fated family trees. Sarri also suggests parenting training, substance abuse and mental health treatment, workforce development, and community organization to relieve disorganization. These preventative services could help redirect families before there’s a problem.