Aug 30, 2014 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, Innovative Methodology, International, Law

Post developed by Katie Brown and Muzammil M. Hussain.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Post-Arab Spring Formations of the Internet Freedom Regime,” was a part of the Political Communication panel “From the Middle East to the Million Man March: The Continuing Digital Revolution” on Saturday August 30th, 2014.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

In early 2011 through 2012, unexpected uprisings cascaded throughout the Arab World. News of this Arab Spring swept across the globe, which inspired several other cascades of political change. Communication systems, especially social media networks, offered an immediate and intimate glimpse into these movements, their successes and failures. So how have state powers and political activists responded to the political capacities of this shared and global digital infrastructure?

Communication Studies Assistant Professor and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Faculty Associate Muzammil M. Hussain studies the political economy of Internet freedom activism. In particular, he is interested in the fate of digital infrastructure in “born digital” states, or states which had successful regime changes that were enabled by digital media. The Arab Spring presents a fascinating and recent moment to consider these “born digital” states. Hussain asks what role governments – both the challenged authoritarian states and the emerging democracies – are playing in shaping communication networks. To address this, he focuses on the transnational activities of political activists promoting Internet freedom.

Hussain conducted fieldwork in the Middle East, North Africa, Western Europe, and North America between 2012-2013, after the Arab Spring protests subsided and a new kind of policy activism took root. Through this international network ethnography of policy makers, communications corporations, and political activists involved in the Arab Spring, Hussain collected a massive array of data. The data includes both interviews and participant-observation, with corroborative evidence of 5,000 individuals and their 84,000 social ties, as well as over 2,000 emails generated through their lobbying and activism work.

This meta-database encompasses the three main stakeholders in Internet freedom promotion: state powers, technology providers, and civil society actors. Hussain argues that Western democracies have been important and successful in launching several major initiatives for securing internet freedom and supporting digital activists currently working within repressive political systems. But these efforts to establish an Internet freedom policy regime are currently gridlocked in competing “communities of practice.”

On the one hand, the community of state-based stakeholders have come to narrowly regard digital media as a critical infrastructure, overvalued its significance as an economic interest and undervalued its significance to democratic activists. On the other hand, since the Arab Spring, the community of tech-savvy political activists has moved rapidly into many new communications policy arenas. Finally, revelations of warrantless surveillance by several advanced democracies have also threatened the viability of this Internet freedom regime. So what are democratic activists and Internet freedom promoters left to do? Stay tuned for Hussain’s next book project: Securing Technologies of Freedom: Internet Freedom Promotion after the Arab Spring.

Jun 18, 2014 | Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Michael Traugott, with input from Ghaydaa Yehia Fahim Ali.

In 2008, Qatar University formed a partnership with the University of Michigan‘s Institute for Social Research (ISR) and Center for Political Studies (CPS) to develop a world-class public opinion research organization at Qatar University, the Social And Economic Survey Research Institute (SESRI). The partnership includes, among other activities, collaboration on organizational structure, recruitment and hiring, design of technical facilities, research, and analysis. As part of the cooperation, University of Michigan researchers also run training workshops in Qatar several times per year. Participants for the workshops come not only from Qatar University, but other private and public organizations from Qatar and throughout the Gulf region. Topics for the workshops have included research design, questionnaire design, cognitive interviewing, data analysis, and sampling. The workshops are structured as lectures, with group exercises integrated into the flow. Between days, participants complete thought exercises to spur discussion the next day.

Photograph from first training workshop of 2014

This year, SESRI hosted three workshops. In the first workshop, which was delivered by ISR researchers Nancy Burns, Ted Brader, Kenneth Coleman, Allen Hicken, and Ashley Jardina, trainees were introduced to key SPSS concepts and notions of hypothesis design and formulation. Causal inferences and random sampling were key areas of discussion.

Traugott and Lepkowski shake hands with a workshop participant at “commencement”

Michael Traugott of CPS and James Lepkowski of ISR’s Survey Research Center (SRC) traveled to Qatar to administer the second workshop, a course on sampling and weighting methods and techniques. Arriving Friday, the team took the weekend to adjust to the eight-hour time change and set up for the training. Monday through Thursday, sessions ran from 9:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., with a break in the middle for lunch and prayers.

Lepkowski interacts with workshop participants

Materials from sampling courses previously taught by Lepkowski were adapted with consideration of language and culture. Courses are taught in English with an Arabic translator on hand, while all materials are available in both languages. Technical terms associated with social science concepts and principles were provided in a glossary, in which some terms were accompanied by animations created by Rafael Nishimura to illustrate the ideas with video. Furthermore, all exercises were designed to be completed in Excel for reasons of accessibility. At the end of the course, Excel spreadsheets with key formulas were provided to all participants.

Traugott returned in May, along with Elizabeth Gerber, Ann Lin, and Monica Bhatt to facilitate a workshop on policy evaluation and spur debate on the purpose of evaluation in public policy, the primary components of policy and program evaluation, and methods of designing preliminary, defensible program evaluations. Workshop materials were tailored to ensure local relevance, including the identification of public policy issues in the cases of Qatar’s traffic woes and evaluations of changes to the education system in Qatar.

The workshop series has caught the attention of the Qatari press. The Qatar Tribune wrote that “The trainees who came from backgrounds in statistics and other diverse fields found the workshops to be useful in introducing them to concepts outside their direct frame of work.”

More than 100 beginner and intermediate-level researchers benefited from the workshops this year, which continue to grow in popularity. More information about the workshops can be found here.

May 15, 2014 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and William Zimmerman.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Russian President Vladimir Putin often makes headlines. This week, U.S. sanctions against Putin in the wake of the Ukraine crisis dominated the news, while Putin’s rewrite of recent music history appeared in popular culture news. Why is Putin such an interesting figure in America? Is it because he challenges our notions of “normal”?

On April 27, Princeton University Press released Ruling Russia: Authoritarianism from the revolution to Putin, the latest book by Center for Political Studies (CPS) Professor Emeritus William Zimmerman. Ruling Russia traces Russia’s history over the last century. The definition of normalcy varied with Russia’s leaders. Gorbachev and Yeltsin for all their differences conceived normalcy to correspond with Western political systems while the leaders of the failed coup against Gorbachev in 1991 and Putin more recently have defined normal to equate with stability, security, and absence of change.

Zimmerman argues that there have been plural Soviet systems and plural Russian political systems and provides a typology to encompass the government types across the century from the revolution to today which distinguishes among democratic, competitive authoritarian, full authoritarian, and totalitarian regimes.

With that as background we can consider the last two decades to better understand current politics in Russia. From 1996 to 2008, after a brief move toward democracy, Russian elections became less open, less competitive, and more meaningless. This time period witnessed Putin’s first (2000) and second (2004) election to President. With Putin unable to run for a third consecutive term in 2008, Dmitry Medvedev ran for President and Putin became Prime Minister.

Then, Medvedev and Putin “castled” in 2012, with Putin running again for President and Medvedev being named Premier. While some believe this move was agreed upon between Putin and Medvedev back in 2008, there is no evidence of this. Zimmerman believes Putin put forth the idea in 2011. Regardless, and interestingly, the 2011-2012 election cycle was more competitive and less predictable than its predecessors. Putin ran a campaign supporting the status quo, stability, and nationalism – a return to normalcy.

The book’s historical analysis ends in 2013. Zimmerman sees full authoritarianism as the most likely near term evolution. This would map onto recent events, including the crackdown on homosexuality during the Sochi-hosted Olympics and military aggression in Ukraine.

From an American vantage point, each move away from democracy was a move away from normal. But for Russia, the idea of “normal” moved toward authoritarianism.

Zimmerman dedicates the book to his students, stating that insights from their dissertations inspired multiple parts of the book.

Mar 5, 2014 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Muzammil Hussain

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In recent weeks, massive protests have swept through Venezuela and Ukraine. Instagram and Twitter have been featured as playing a key role in the latter. Digital activism is increasingly attributes to helping spark rapid waves of mobilization across several recent international cases.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate and assistant professor of communication Muzammil Hussain studies the role of technology in protest. With Philip N. Howard of the University of Washington, Hussain published an article weighing the roles of Internet infrastructure and mobile telephony in the Arab Spring mobilizations.

Though in a different area of the world, understanding the role of communication systems, the political uses of digital media, and the politicization of internet infrastructure in the Arab Spring can help shed light on the current wave of democratization. Hussain argues that information technologies do not cause political change, but they have become a consistent tool and space to afford and act out political contentions.

To understand the relative success of the Arab Spring across different countries in the Middle East and North Africa, the authors look at a variety of contextual factors, including income, wealth distribution, unemployment, demographics, digital connectivity, censorship, and economic dependence on fuel. In the article, they examine the impact of these factors on regime fragility and social movement success. Interestingly, they argue that the inciting incidents in each country were digitally mediated. The describe how digital communication sets off a six-stage process of political mobilization experienced in both successful and failed attempts for regime change.

The authors conclude that “information infrastructure – especially mobile phone use – consistently appears as one of the key ingredients in parsimonious models for the conjoined combinations of causes behind regime fragility and social movement success.” That is, digital communication networks, especially mobile phones, drive political upheaval. In addition to offering insight into the Arab Spring experiences, this may also help explain the recent successful ousting of Ukraine’s president.

Feb 6, 2014 | Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Yuen Yuen Ang.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

What hobbles online activism in autocracies? The intuitive answer: repression. In a recent article titled “Authoritarian Restraints on Online Activism Revisited: Why ‘I-Paid-A-Bribe’ Worked in India but Failed in China” in Comparative Politics, Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate, assistant professor of political science, and Center for Chinese Studies faculty associate Yuen Yuen Ang looks beyond repression — she brings attention to the deeper organizational problems rooted in authoritarian rule.

In 2008, social activists in India created www.ipaidabribe.com (IPAB), a crowd-sourcing website that collects anonymous reports of bribe extraction. By 2014, more than three million users visited India’s IPAB site, with over 20,000 bribe reports filed. Major news outlets covered IPAB. And IPAB soon spread to 17 other countries, including China in 2011.

But, whereas IPAB flourished in India, within two months, all of China’s IPAB sites disappeared. Why?

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Given that China is an authoritarian state, the assumption is that censorship and repression killed the sites. As asserted in the New York Times:

“They [IPAB sites] are threatening enough that when a rash of similar sites popped up in China last summer, the government stamped them out within a couple of weeks.”

Ang’s research, however, finds a more nuanced and complex story. Chinese authorities did not in fact stamp out the sites resolutely, but instead wavered between approval and suppression. More importantly, even before the final shut-down, the IPAB sites had already begun to crack from internal organizational problems. Chinese netizens used the sites to vent, exact personal revenge, and even extract profit and bribes from posting reports.

These problems are rooted in prolonged restrictions that deprive China’s civil society the opportunity to learn the norms of constructive participation and to professionalize. Anonymity on the Internet exacerbates the challenges of self-governance.

Thus, Ang cautions against sanguine views about the revolutionary power of online activism in checking corruption and authoritarian power. The challenge of civic empowerment runs deeper than escaping the shackles of repression. As she concludes,

“Authoritarian rule provides an inhospitable environment for nurturing online citizenship in the full sense of the word, involving not only the exercise of rights and free speech, but also accountability, responsibilities, and trust.”

Commentaries on Ang’s article have appeared on the websites of Personal Democracy Media, ipaidabribe.com, and cnpolitics.org.

Jan 29, 2014 | Foreign Affairs, International, Law

Post developed by Katie Brown.

2013 came in at the fourth hottest on record. Yet, the Alberta Clipper plummeted the nation’s temperatures this week, a return of the polar vortex that descended earlier this month. These extreme weather patterns have renewed debate over climate change.

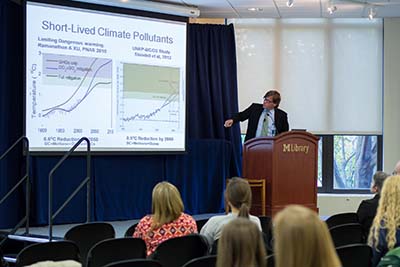

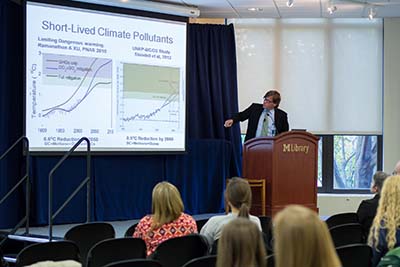

Recently, the Center for Political Studies (CPS) featured an expert on national agreements around climate change as part of their Harold Jacobson lecture series. Established in 2002 to honor Jacobson, the Jacobson Lecture is an annual talk by leaders in the fields of international organization, international law, foreign policy, and the environment.

This year, CPS welcomed David G. Victor, a professor at the School of International Relations and Director of the Law and Regulation Laboratory at the University of California, San Diego. In his talk entitled, “The Global Climate Crisis: Will International Cooperation be Effective?,” Victor outlined a rather dire situation around international law concerning the climate. Despite the current state of affairs, Victor posited that we are at a turning point.

Photo credit: Eva Menezes

To leverage this turning point effectively, Victor pointed to four key things that can make for more effective international negotiations:

- Create flexible “clubs” instead of global treaties. That is, stop thinking about the climate as a global problem. Instead, set up small groups that take direct responsibility for parts of the problem.

- Celebrate the lower emissions enabled by technological innovation. These advances are fortuitous and promise to keep helping the situation.

- Focus on solidifying and clarifying trade rules.

- Seek small steps in the right direction. Or, as Victor describes it, seek “singles and walks, not homers.”

Victor’s conclusion hits notes of optimism. The last twenty years have not worked, he laments. But the system is headed in the right direction. Following the four steps outlined above will help steer us toward more effective, cooperative climate regulation.