Jan 2, 2014 | Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Ronald Inglehart.

The World Values Survey tracks values and cultural change over time and across the world. Conducted in five waves from 1981 to 2007 – with a sixth wave being collected now – the survey samples from 90% of the world’s population.

The World Values Survey is especially interested in human empowerment. To map the process of empowerment, World Values Survey researchers created the Utility Ladder of Freedoms. Climbing the ladder means moving from a life based in threats to a life based in opportunity. Nations can climb the ladder as their citizens have more ways to improve their daily lives, like education. Typically, the higher a nation climbs on the ladder, the more universal freedoms are tolerated and practiced within that nation. Here, we use the ladder to take a closer look at the country of Turkey.

In August 2013, the Center for Political Studies (CPS) Blog featured a post about the protests in Turkey, suggesting that the government’s violent response was related to Turkey’s weak democracy. Since that time, the protests in Turkey have settled down. However, Turkey’s bid to host the 2020 Olympics has replayed some of these earlier tensions. Some have expressed that the political transformation and violence would make the selection of Turkey a risky choice. After Japan was instead selected to host the 2020 Olympics, some Turkish citizens actually celebrated, using the opportunity to criticize the Turkish government.

So, where is Turkey in its climb up the Utility Ladder of Freedoms?

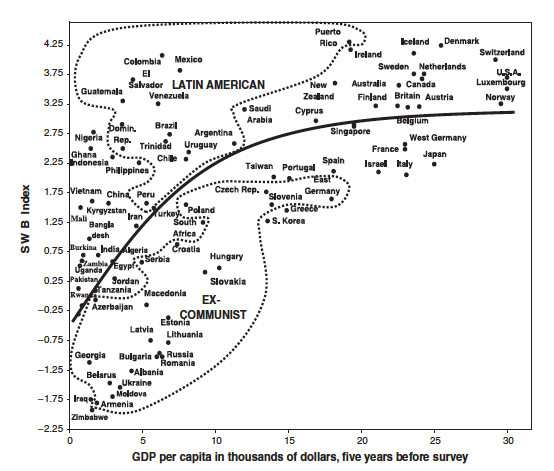

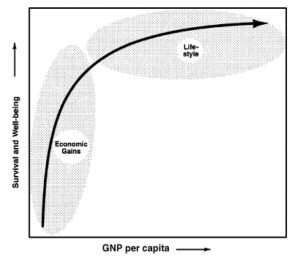

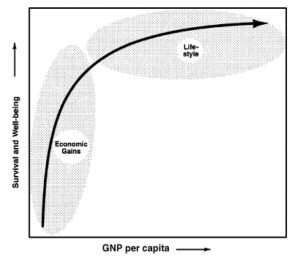

Let’s start with Happiness. The World Values Survey asks about happiness and life satisfaction – what we’ll call Subjective Well Being. An article by CPS Researcher Inglehart, Roberto Foa of Harvard University, the late pioneer of positive psychology Christopher Peterson, and Christian Welzel of Germany’s Leuphana University, looks at the determinants of Subjective Well Being. As the chart to the left shows, Subjective Well Being rises very quickly as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rises, but then levels off. An earlier Inglehart study from 1991 also finds a connection between GDP and life satisfaction. So, earning more money means higher well being, but only to a point.

Let’s start with Happiness. The World Values Survey asks about happiness and life satisfaction – what we’ll call Subjective Well Being. An article by CPS Researcher Inglehart, Roberto Foa of Harvard University, the late pioneer of positive psychology Christopher Peterson, and Christian Welzel of Germany’s Leuphana University, looks at the determinants of Subjective Well Being. As the chart to the left shows, Subjective Well Being rises very quickly as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rises, but then levels off. An earlier Inglehart study from 1991 also finds a connection between GDP and life satisfaction. So, earning more money means higher well being, but only to a point.

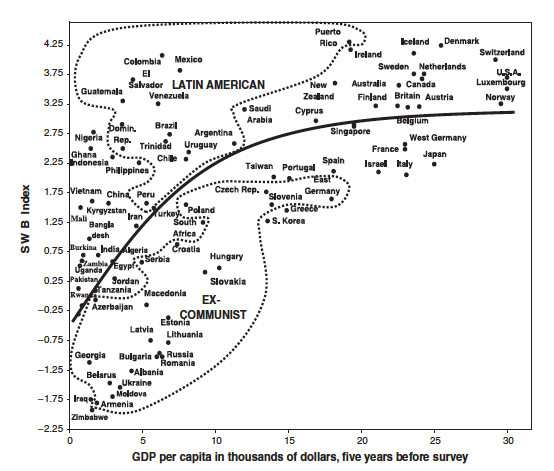

Now let’s consider Turkey. The graph below plots the GDP of specific countries against their reported Subjective Well Being. Turkey has a lower GDP and a Subjective Well Being at the mid-point between survival and well being. Inglehart’s earlier work finds that the as Subjective Well Being increases, so does democratic potential. So, Turkey’s mid-level happiness correlates with its weak democracy.

Subjective Well Being vs. GDP

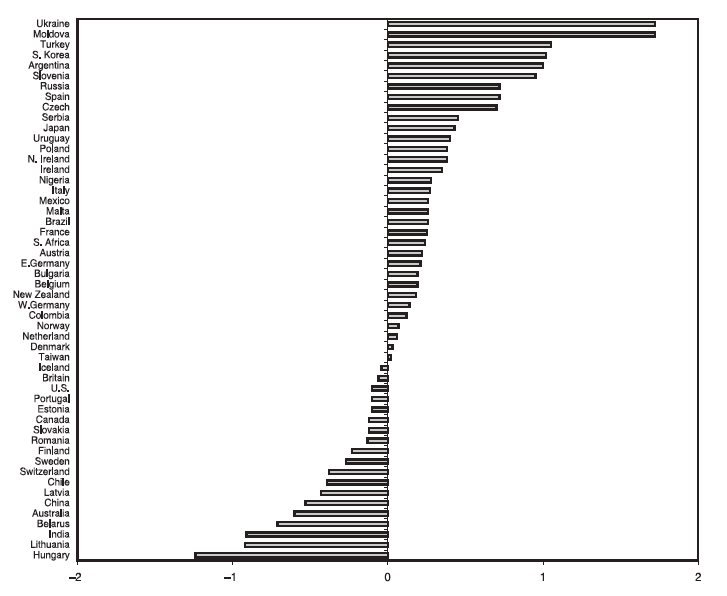

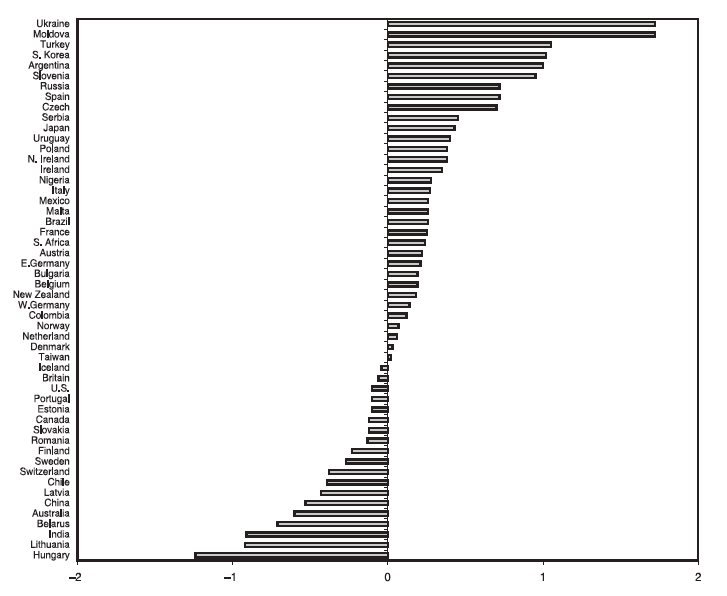

But, Turkey’s Subjective Well Being is on the rise. The chart below shows that Turkey’s Subjective Well Being is increasing faster than most other nations. By that logic, Turkey’s democratic potential should also be on the rise.

Subjective Well Being

Position on the Utility Ladder of Freedoms depends on choice, equality, autonomy, and voice – all qualities that also act as keys to democracy. Turkey’s Subjective Well Being and its potential for democracy are on the rise. So, Turkey seems poised to climb the ladder. However, the sometimes disconnect between the country’s government and citizens, occasionally to violent ends, suggests that moving up the ladder can be a rough climb.

Dec 19, 2013 | Foreign Affairs, International, Profile

Developed by Katie Brown and Mark Tessler

If you ask Mark Tessler about the trajectory of his work, he smiles. His career path was never planned; rather he took advantage of unexpected opportunities along the way. Among these was the chance to spend part of his undergraduate education as a student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and part of his graduate education as a student at the University of Tunis.

If you ask Mark Tessler about the trajectory of his work, he smiles. His career path was never planned; rather he took advantage of unexpected opportunities along the way. Among these was the chance to spend part of his undergraduate education as a student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and part of his graduate education as a student at the University of Tunis.

Since completing his studies, Tessler has conducted research in Tunisia, Morocco, Israel, the West Bank, and Egypt. He has also lived and taught university in several Sub-Saharan African countries.

Not surprisingly, one of Tessler’s areas of research is the Israel-Palestine conflict. Spending time in both Israel and Palestine has enabled him to witness first-hand the legitimate aspirations of both sides and has shaped his perspective on the conflict. He has published extensively on the subject. His scholarship, which emphasizes rigor as well as political and cultural sensitivity, includes articles in World Politics, the Journal of Conflict Resolution, International Studies Quarterly, and a prize-winning 1000-page book, A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Tessler describes his approach to the conflict as “objectivity without detachment.”

Tessler’s broader research questions focus on the individual-level of analysis and investigate the normative and behavioral orientations of ordinary citizens in the Middle East and North Africa. In particular, he studies how people sort out who they are, what kind of society they want to live in, and by what kind of political system they want to be governed. Some of the findings from this research are brought together in his 2011 book, Public Opinion in the Middle East: Survey Research and the Political Orientations of Ordinary Citizens.

Currently, Tessler is working on a new and original public opinion database. With support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the database pulls together data from 44 nationally-representative surveys conducted in 15 countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Tessler carried out some of these surveys with support from the National Science Foundation and other foundations and agencies. Other surveys are from the Arab Barometer, which Tessler co-directs, and from the World Values Survey.

Key variables in this unique database include respondent attitudes toward a wide range of political and social issues, particularly those pertaining to governance and to Islam. Also included are major political, economic, and demographic characteristics of the country of which the respondent is a citizen. The database thus permits both separate and integrated individual-level and country-level analyses.

Though not planned, Tessler’s choice to dive into opportunities as they appeared helped to create an illustrious career. He has authored, coauthored, or edited 15 books and published over 125 book chapters and journal articles. Mark Tessler is a Center for Political Studies (CPS) Researcher and Samuel J. Eldersveld Collegiate Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan.

Dec 13, 2013 | Foreign Affairs, Innovative Methodology, International

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Robert Franzese

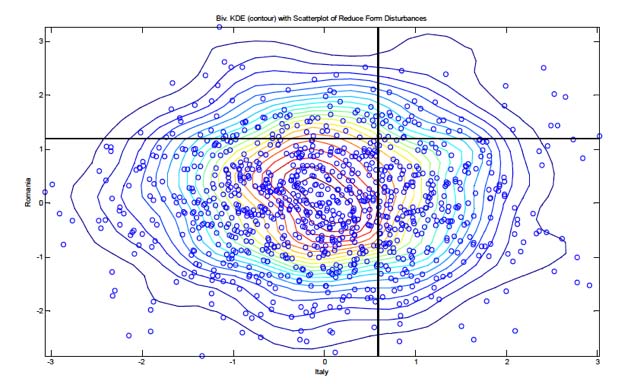

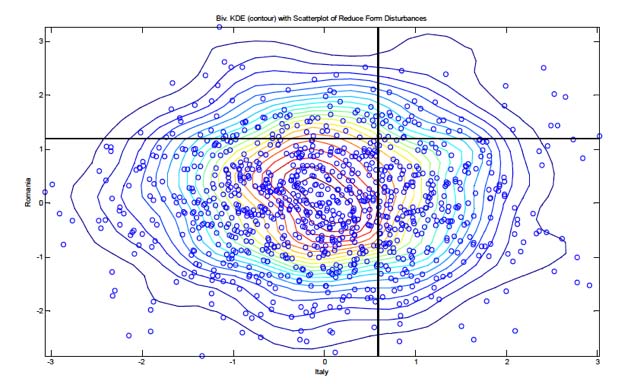

The map to the left shows Europe during World War I, including Italy and Romania. Can a graph illustrate how Italy’s decision to enter the war influenced Romania’s decision to do so?

The map to the left shows Europe during World War I, including Italy and Romania. Can a graph illustrate how Italy’s decision to enter the war influenced Romania’s decision to do so?

Social scientists seek to understand social, political, and psychological phenomena. Quantitative research methods used by scientists can help investigate what factors cause specific outcomes (effects). Often, however, a factor in one unit causes an outcome in that unit, and that outcome then becomes a factor that causes outcomes in other units. Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher and Professor of Political Science Robert Franzese, along with his coauthor and former member of CPS Jude Hays, has been studying ways to understand the relationships not just between cause and effect in one unit, but between causes and effects across multiple units, over time. That is, how to identify and estimate what is called spatial and spatiotemporal interdependence.

Franzese, along with Hays and their colleague Lena Schaeffer, presented a paper at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA) that outlines the shortcomings of most approaches to the connection between causes and effects across multiple units over time. Then, the paper highlights some more promising models.

To illustrate how these more promising models work, let’s consider a specific application: investigating the decision of nations to enter World War I. This decision depends not only on domestic and international structural factors, but also on the decision of other nations to enter the war.

With this in mind, how did Italy’s decision to enter World War I influence Romania’s decision to do so? The below graph shows a simulation of 1,000 different possible outcomes (as dots on the graph), using Franzese’s model. From the set of simulations on the graph, we learn that when Italy joins the war (as indicated by the number of dots which appear to the right of the vertical cutoff line), Romania also joins the war 15.6% of the time (as indicated by the number of dots which appear above the horizontal cutoff line). Furthermore, when Italy does not join the war, Romania still joins the war 12.3% of the time. The difference between these two numbers – 3.3% – is thus the the impact of Italy’s decision to enter the war on Romania’s decision to enter the war.

This simulation is just one illustration of an application of spatiotemporal interdependence. Models such as these can help social scientists understand a variety of scenarios where interdependence occurs, with some of many other examples being:

- the relationship between the votes of legislators, the votes of citizens, and election results;

- the outcomes of coups, revolutions, and riots; and

- the entry of countries into treaties or alliances.

Oct 28, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Mark Tessler.

Egypt attracted international attention as a key participant in the Arab Spring. Along with Tunisia, it was among the first countries to witness the fall of a decades-long authoritarian regime. In early 2011, protestors demanded that then Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak step down. In February 2011, Mubarak relented, turning over power to the military.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In November of 2011, the country held parliamentary elections and these were won by the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party. In June of 2012, the Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi was elected president of Egypt. Over the next year and a half, Morsi pushed remaining officials from Mubarak’s reign out of government, all the while consolidating his power.

With the economic situation deteriorating, and with conflicting claims about who was responsible, anti-Morsi protests spread throughout Egypt in summer 2013. Then, on July 3, 2013, in response to the growing unrest, the military removed Morsi from office. Violent clashes between the military and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood followed and have continued sporadically since that time.

A key question raised by these events, and by post-Arab Spring developments in a number of other Arab countries, concerns the role to be played by Islam in government and political affairs. As expressed by Egypt’s Grand Mufti in April 2011, following the ouster of Mubarak, “Egypt’s revolution has swept away decades of authoritarian rule but it has also highlighted an issue that Egyptians will grapple with as they consolidate their democracy: the role of religion in political life.”

Center for Political Studies (CPS) Researcher and Samuel J. Eldersveld Collegiate Professor of Political Science Mark Tessler is making major strides to understand what ordinary citizens in Egypt and other Arab countries think about the complicated and contested relationship between religion and politics in the Middle East. Among the data on which Tessler is drawing is the multi-country Arab Barometer survey project, which Tessler co-directs. Arab Barometer surveys in Egypt in 2011 and 2013 offer insights about how recent events have influenced the way the Egyptian public thinks about Islam’s political role.

One finding from these surveys is that most Egyptians believe democracy and Islam to be fully compatible, and this view did not change between 2011 and 2013. On the other hand, while most Egyptians have confidence in Islam itself, there has been a dramatic decrease over this period in the proportion that believes that the country is better off when religious people hold public office. Some Egyptians describe this as wanting Islam but not Islamists.

These Arab Barometer surveys are part of a larger dataset pertaining to Islam and governance that Tessler has constructed with support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The dataset pulls together information from 44 nationally representative surveys conducted in 15 countries in the Middle East and North Africa and includes not only respondent political and social attitudes but also major characteristics of the country of which the respondent is a citizen.

Tessler’s analysis of these data will be published in a forthcoming book, Islam and the Search for a Political Formula: How Ordinary Citizens in the Muslim Middle East Think about Islam’s Place in Political Life. The book will offer a deeper understanding of the desired role of Islam in politics across the Middle East, a religion and region often misrepresented in American media, politics, and minds. In addition, the database will be placed in the public domain for use by other scholars who study the relationship between religion and politics.

Oct 14, 2013 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with James Morrow.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

The horror in Syria has gripped international attention, especially in recent weeks with the release of images of those killed by chemical weapons. But why would Bashar al-Assad, the President of Syria, use chemical weapons when he is winning the civil war against insurgents?

Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor and A.F.K. Organski Collegiate Professor of World Politics James Morrow recently spoke to this issue on MSNBC’s The Last Word. Assad’s target was a rebel controlled neighborhood in Damascus, the capital of Syria. A large chemical attack would scare other civilians, inducing them to flee for safety. After they left, Assad could move his forces into one the few remaining rebel areas. Morrow also highlights the timing of Assad’s chemical strike: it occurred after the rebels began to lose ground across Syria. Assad used chemical weapons precisely because he is winning.

Morrow’s comments on MSNBC are grounded in his research. In a forthcoming book, Order Within Anarchy, Morrow models violations of the laws of war, like the use of chemical weapons. Violations typically come early in war. When they come later – as in Syria – violations tend to be perpetrated by the winning side. The violation itself increases the perpetrator’s chance to win the war. Thus, Assad’s deployment of chemical weapons could be seen as a coup de grâce.

Yet, Assad also faced a strong global backlash. Obama declared a red line crossed and seemed poised to order counter-attacks on Assad. Such a strike could undo any gain from the chemical weapons. But, Russia – who, with China, blocked approval to counter-attack Syria in the United Nations – proposed an alternative solution: order Assad to surrender his chemical weapons for destruction by international monitors. Obama and Assad agreed to this approach. Last week, Assad received praise for his steps to chemically disarm. And also last week the Nobel Prize committee awarded the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons with the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to disarm Syria. But the gains of his use of chemical weapons remain.

Sep 3, 2013 | Current Events, Elections, Foreign Affairs, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Allen Hicken.

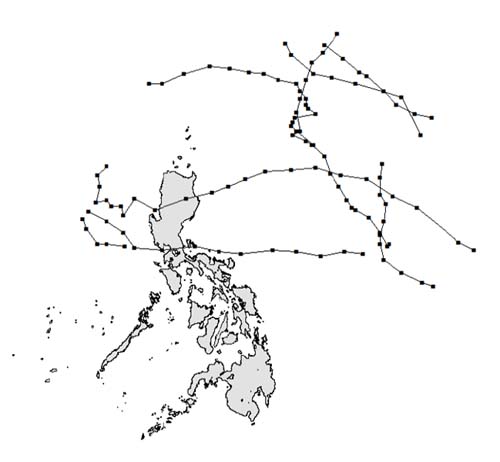

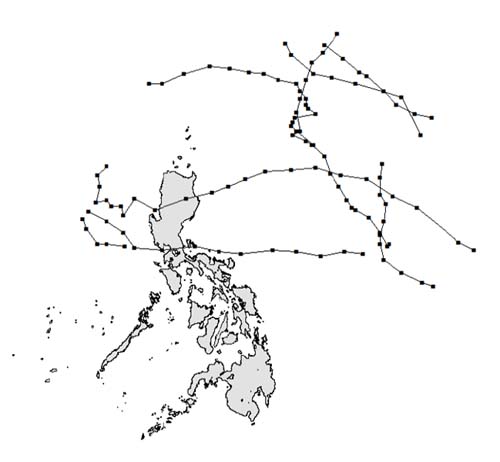

Each year, 30 typhoons and tropical storms batter the Philippines. The damage costs between $17 and $19 million per year, nearly 10 percent of the nation’s GDP. The Japanese Meteorological Agency developed a storm tracking system that measures date, time, location, wind speed, barometric pressure, and storm type every six hours. The map below displays the paths of storms striking the country in 2010.

In addition to tracking typhoons, could this map also help gauge the role of political affiliations in the distribution of public resources, a.k.a., pork barreling? Enter the work of Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher Allen Hicken, who is also Director of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies and Associate Professor of Political Science. In a forthcoming paper, “Pork & Typhoons: The Political Economy of Disaster Assistance in the Philippines,” Hicken, along with graduate students James Atkinson and Nico Ravanilla, developed a new approach to studying pork barreling.

Specifically, the research uses a storm index created by University of Michigan faculty member Dean Yang to create a baseline of expected relief fund distribution and trace variations by political ties. The Philippines’ democracy is both one of the oldest and weakest in Asia. Political clans are central to Filipino political life. The research considers political ties both in terms of party links and clan connections between a politician and a region.

To what extent do political calculations affect the allocation of government disaster reconstruction funds? The results show that need does indeed impact relief received. However, the authors also find that, “Political ties between members of congress and local mayors, especially clan ties, increase per capita targetable funds allocated to that municipality.” Thus, tracking typhoons can expose pork barreling.

Though typhoons and clan ties may be unique to the Philippines, natural disasters and pork barreling are global phenomena. Thus, the innovative methodology pioneered in this paper could be applied to other nations to increase understanding of political ties and resource allocation.

Let’s start with Happiness. The World Values Survey asks about happiness and life satisfaction – what we’ll call Subjective Well Being. An article by CPS Researcher Inglehart, Roberto Foa of Harvard University, the late pioneer of positive psychology Christopher Peterson, and Christian Welzel of Germany’s Leuphana University, looks at the determinants of Subjective Well Being. As the chart to the left shows, Subjective Well Being rises very quickly as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rises, but then levels off. An earlier Inglehart study from 1991 also finds a connection between GDP and life satisfaction. So, earning more money means higher well being, but only to a point.

Let’s start with Happiness. The World Values Survey asks about happiness and life satisfaction – what we’ll call Subjective Well Being. An article by CPS Researcher Inglehart, Roberto Foa of Harvard University, the late pioneer of positive psychology Christopher Peterson, and Christian Welzel of Germany’s Leuphana University, looks at the determinants of Subjective Well Being. As the chart to the left shows, Subjective Well Being rises very quickly as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rises, but then levels off. An earlier Inglehart study from 1991 also finds a connection between GDP and life satisfaction. So, earning more money means higher well being, but only to a point.