Learning from Gallup’s Missed Prediction in 2012 Election

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Michael Traugott.

In the American presidential election of 2012, most polls predicted a narrow win for Democratic incumbent Barack Obama over Republican challenger Mitt Romney. But on November 5, 2012, Obama won both the popular vote (62,611,250 to 59,134,475) and the Electoral College (332 to 206) by a comfortable margin.

Most major polling organizations underestimated Obama’s votes, yet closely targeted Romney’s outcome. Gallup and Rasmussen, on the other hand, overestimated Romney’s vote share, projecting that he would win.

In order to understand its error and, more importantly, correct its estimation for future elections, Gallup called upon Professor of Communication Studies and Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor Mike Traugott. Traugott studies public opinion, survey methodology, and voting technology, with more than 100 articles and book chapters and 12 books published.

Traugott’s connection to the project goes beyond his expertise. Early in his career, he worked for Gallup founder George Gallup. Traugott has also served as president of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR). In 2008, he chaired an AAPOR committee to investigate the causes of an industry-wide estimation error in the New Hampshire primary. As a follow up, AAPOR launched an initiative to make polling practices more transparent. Though the initiative garnered initial support, it hasn’t matured as rapidly as hoped because many commercial firms are reluctant to expose their proprietary methods. Yet, given the widespread mispredictions of 2012, Gallup agreed to make its investigation transparent as a service to the public and the pre-election polling profession.

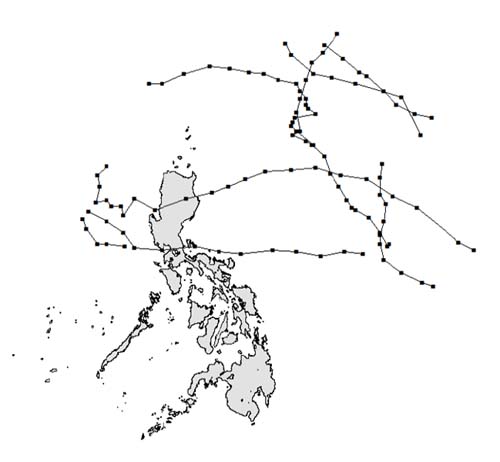

Gallup’s initial investigation, led by Traugott and published here, identifies several potential contributing factors to the errant projection. The main problem appears to lie in the sampling design. Gallup interviews potential voters using only a combination of listed landline and cell phones. Because listed landline users are more likely to be conservative, Gallup’s respondent pool skewed conservative. Other potential factors include giving more weight to past voting behavior than other polls, time zone issues, and the format of race and ethnicity questions. Further, Gallup, like other major polling organizations, does not take the candidates’ campaign effort into account. As this map illustrates, in 2012, the candidates focused most of their campaign spending in battleground states, which in turn impacted turnout and vote choice by state.

In response to the report, Gallup has brought in a team of researchers which will test the hypotheses derived from the initial report during the 2013 New Jersey and Virginia gubernatorial elections. Traugott is also leading a graduate seminar this fall at the University of Michigan that will allow students to participate in the design of the experiments and analyze data related to the inquiry. According to Traugott, this is a “very unusual, almost once in a lifetime chance to combine real world applications of conceptual and theoretical issues about survey design.”