Oct 10, 2014 | ANES 65th Anniversary

Post developed by Paul R. Abramson (Michigan State University), John H. Aldrich (Duke University), Brad T. Gomez (Florida State University), and David W. Rohde (Duke University).

This post is part of a series celebr ating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science.

ating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science.

Change and Continuity is a soon-to-be 18 book series that Abramson, Aldrich, and Rohde began in the 1980 election. Gomez joined the team for the 2012 edition; all 18 will have been published by CQ Press.

Our plan was to get the best possible empirical analysis of the 1980 elections to students so that they could get a rich view of elections, indeed of the best possible science about public opinion and voting behavior, on their desks as quickly as possible. We drew from a number of sources, but there was never a question in our minds that the book would ever be anything but one based primarily on the ANES data. Those data were and are today the best data for teaching about American elections, as it is the best data for learning about and researching about elections. It is the “gold standard” in survey data.

The ANES was already a body of 30 years of electoral and attitudinal data when we started. It has been our good fortune to be writing Change and Continuity for over 30 years. The standards of quality are the continuity, even though there have been a variety of changes in the questionnaire, sampling methods, and survey mode, reflecting scientific advances in surveying the public.

The main advantage of the additional 30 years’ perspective, however, has been enriching the historical perspective on elections. Scholars and pundits have long drawn on previous elections in making their assessments of parties, candidates, and electoral outcomes. Now, however, we can add a serious understanding and 65 year perspective on the public as the foundation of elections. What has changed and what is continuous in the public can tell us much about how democracy works. The ANES completes what is most everywhere else an otherwise incomplete picture of democracy.

Oct 7, 2014 | Innovative Methodology, International, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown and Ugo Troiano.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

Around the globe, the average maternity leave is 118 days, but with a lot of variation. Maternity leave periods range from 45 days in Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates to 480 days in Sweden. Why the difference? And, moreover, does the variation relate to gender discrimination?

Assistant Professor of Economics and Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate Ugo Troiano, along with Yehonatan Givati of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Law School, investigated these questions and published their results in an article in The Journal of Law and Economics.

Their core theory is simple: maternity leave is costly to employers, so when the government mandates long periods of maternity leave, women may be discriminated against and receive lower wages as a result. However, places with a low tolerance for pay gaps won’t let that happen, and the incidence of this policy ends up being shared across genders. As a consequence, it becomes more economically “optimal” to enact longer mandatory maternity leaves in societies that are not discriminatory toward women. This theory is consistent with the empirical evidence.

The authors show that maternity leave is indeed shorter in societies where survey respondents think that men should receive preferential treatment in the workplace. The authors measure this attitude through a World Values Study question that asks level of agreement with, “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” Aggregated to the national level and combined with data on the length of maternity leaves, they find the two are related.

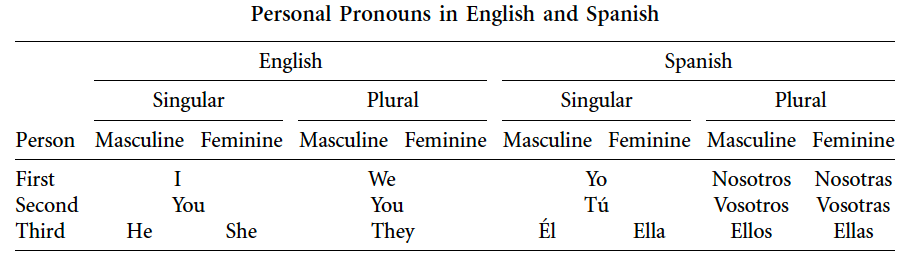

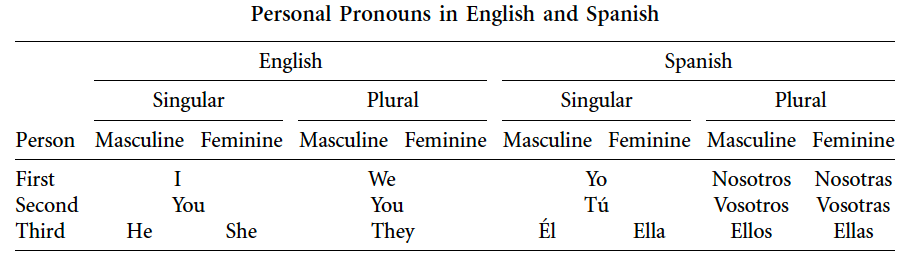

However, that evidence alone does not allow us to conclude that culture is causing a longer leave, because it’s possible that causation goes in the opposite direction: a longer leave is causing more tolerant attitudes toward women. In order to alleviate this concern, Givati and Troiano looked at a proxy from attitudes less likely to change because of maternity leave: language. Specifically, they developed a measure from recent research in psychology and linguistics known as linguistic relativity suggesting that language shapes thought. Following from this, they analyzed the number of gender-differentiated pronouns across languages to see if this corresponded to tolerance of gender discrimination. For example, English uses one gender-differentiated pronoun associated with gender and the number of people referenced, while Spanish uses three (see the table below). In all, Troiano and Givati tallied the number of gender-differentiated pronouns in 33 languages using grammar books, and they looked to see whether the number of pronouns was negatively correlated with gender tolerant attitudes.

The authors indeed find a connection, with more gendered pronouns correlated with greater tolerance of gender discrimination as measured by the World Values Survey question. Next, the authors estimated a regression model, with length of maternity leave as the dependent variable and number of gendered pronouns as the independent variable. Troiano and Givati find that the more gendered pronouns, the shorter the maternity leave. Or, on the flip side, the fewer gendered pronouns, the longer the maternity leave.

Troiano concludes, “This project is an example of how concepts from different social sciences can be used to answer specific policy questions. To understand the factors that affect the variation of maternity leave across countries we integrated economic concepts (incidence of a policy), sociological ones (measuring attitudes from survey) and linguistic ones.”

Oct 2, 2014 | Elections, National

Post developed by Katie Brown and Arthur Lupia.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

In a post last year, Center for Political Studies (CPS) Research Professor and Professor of Political Science Arthur Lupia declared there to be two types of people: those who are ignorant about politics and those who are delusional about how much they know. There is no third group.

If people lack information, it can lead to bad decision-making. As part of an effort to reduce bad decisions, Lupia examines how to inform voters more effectively in his forthcoming book, How to Educate Ignorant People about Politics: A Scientific Perspective.

Lupia focuses on improving the efforts of teachers, scientists, faith leaders, issue advocates, journalists, and political campaigners. How can they best educate others? To further this goal, Lupia focuses on the transmission of information. He clarifies how different kinds of information can improve important kinds of knowledge and competence. A key part of Lupia’s argument is that people are easily distracted and often evaluate information based on how it makes them feel. As a result, the way to improve knowledge and competence is to find factual information that is not only relevant to the decisions that people actually have to make but also consistent with their values and core beliefs. For if a person sees factual information that is inconsistent with their values and beliefs, they tend to ignore it; and if the information is not relevant to their actions, then it cannot improve their competence. In this examination, facts are not enough. The real task is to convey facts to which people want to pay attention.

Despite the pessimistic premise of broad ignorance, Lupia is ultimately optimistic. The central thesis of his book is that offering helpful information is possible. Or as he puts it, “Educators can convey valuable information more effectively and efficiently if they know a few more things about how people think and learn.”

ating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science.

ating the 65th anniversary of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The posts will seek to highlight some of the many ways in which the ANES has benefited scholarship, the public, and the advancement of science.