What do voters really learn from the media about presidential candidates? A new book by experts from the University of Michigan, Georgetown University, and Gallup, Inc., Words That Matter: How the News Media Environment Allowed Trump to Win the Presidency, offers in-depth analysis and conclusions about the information that mattered most in the 2016 presidential election.

Words That Matter is the collaborative work of eight authors: Leticia Bode, Ceren Budak, Jonathan M. Ladd, Frank Newport, Josh Pasek, Lisa O. Singh, Stuart N. Soroka, and Michael W. Traugott. The authors have expertise in a range of disciplines including public opinion, communications, public policy, and computer science, and they take different approaches to the study of campaign media. As a result, the book is nuanced in its handling of news content, social media posts, and survey responses.

There are a number of reasons that the 2016 presidential campaign was exceptional. The media landscape has changed dramatically in recent years, with many people accessing and sharing news through social media. The authors find that news coverage during the 2016 campaign “was more negative than in recent previous presidential campaigns, consistent with these candidates being the most personally unpopular nominees in polling history.”

Words That Matter guides readers through the media’s process of producing information, how that information gets to voters, and what information voters actually absorb. The authors argue that advances in media technology call for new ways to measure the information environment. They address this challenge through innovative surveys and content-analytic research techniques.

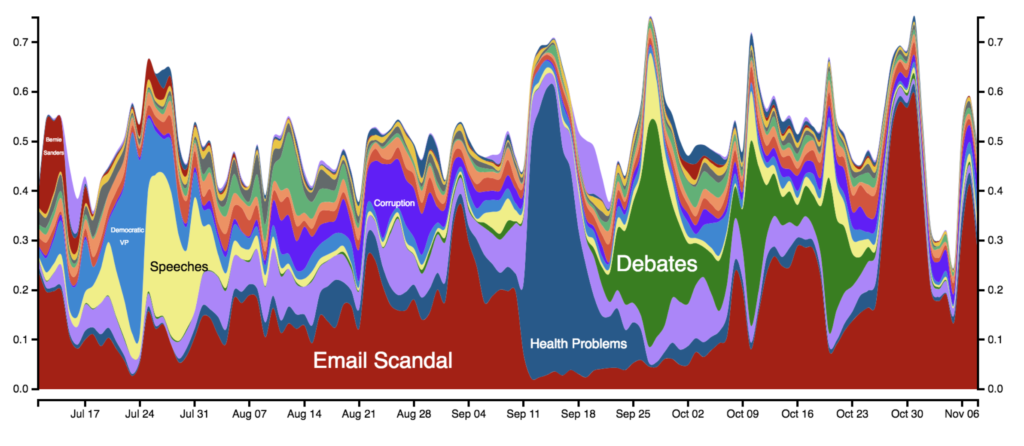

A key finding of the work is that the largely negative campaign played out differently for the two major party candidates: Donald Trump was confronted with a shifting but largely uninfluential series of scandals, whereas Hillary Clinton faced a single, stable, and influential scandal involving her use of a private email server. The authors show that the long-standing nature of the email scandal made it especially sticky in the public mind. They write “Even when there was other news about Hillary Clinton, the public thought about ‘her emails’—for months and months—indeed, starting before the election campaign was even underway.”

Some scholars are skeptical that the media have the power to influence votes, whereas others believe that campaign messaging can have a large effect. The authors show that not all voters are equally open to influence. The most politically-engaged voters are steadfast, while the least engaged are difficult to reach at all. “The fact that middle- and low-engagement voters are the most susceptible to influence,” write the authors, “also helps us understand why the topics given heavy attention in the media environment can be consequential.”

News stories that are repeated over a long period of time are the most likely to be noticed by people who are not highly engaged with politics. The authors also find that telling people how to vote is less effective than simply changing the subject. Voters who don’t follow the news carefully may not remember the details of various scandals, but they do tend to notice if one specific issue garners sustained coverage. Those sustained scandals stand out as more important when voters make their choice.

The authors conclude that media content can indeed shift voter behavior for some voters, and that in a close election like the 2016 presidential election, these effects can be of real consequence.