Post written by Josh Pasek, Faculty Associate, Center for Political Studies and Assistant Professor of Communication Studies, University of Michigan.

If Rick Snyder weren’t the Governor of Michigan, Donald Trump would probably have 16 fewer electoral votes. I say this not because I think Governor Snyder did anything improper, but because Michigan law provides a small electoral benefit to the Governor’s party in all statewide elections; candidates from that party are listed first on the ballot.

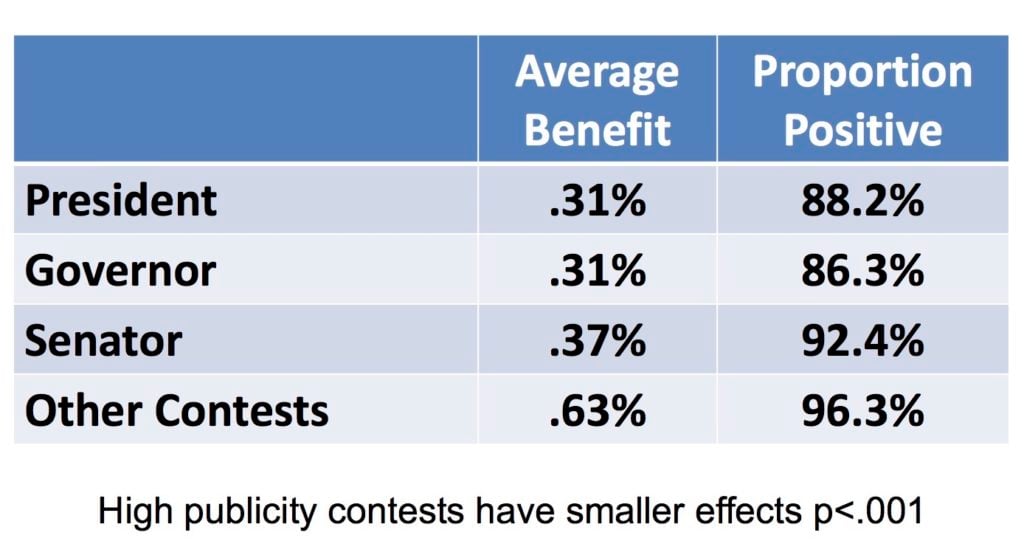

Yesterday, Donald Trump was declared the winner in Michigan by a mere 10,704 votes, out of nearly 5 million presidential votes cast. Although this is not the smallest state margin in recent history – President Bush won Florida and the election by 537 votes and Al Franken won his senate seat in Minnesota by 225 (after the result flipped in a recount) – it represented a margin of 0.22%. The best estimate of the effect of being listed first on the ballot in a presidential election is an improvement of the first-listed individual’s vote share of 0.31%. Thus, we would expect Hillary Clinton to have won Michigan by 0.4% if she were listed first and about 0.09% if neither candidate were consistently listed in the first position.

It may seem surprising to suggest that anyone’s presidential vote would hinge on the order of candidates’ names, but the evidence is strong. In a paper I published with colleagues in Public Opinion Quarterly in 2014, we looked at name order effects across 76 contests in California – one of the few states that rotates the order of candidates on the ballot – to estimate the size of this benefit. We later replicated the results in a study of North Dakota. Both times, we found that first-listed candidates received a benefit and that the effect was present, though smaller, at the presidential level.

There are many reasons that voters might choose the first name, even if they started their ballots without a predetermined presidential candidate. Some individuals might have been truly ambivalent and selected the first name they had heard of (in this case, “Trump”), others may have instead checked the first straight party box – listed in a similar order – without intending to select our new President-elect. Regardless of the cognitive mechanisms involved, the end result is clear – the “will” of the voters can be diverted by seemingly innocuous features of ballot design.

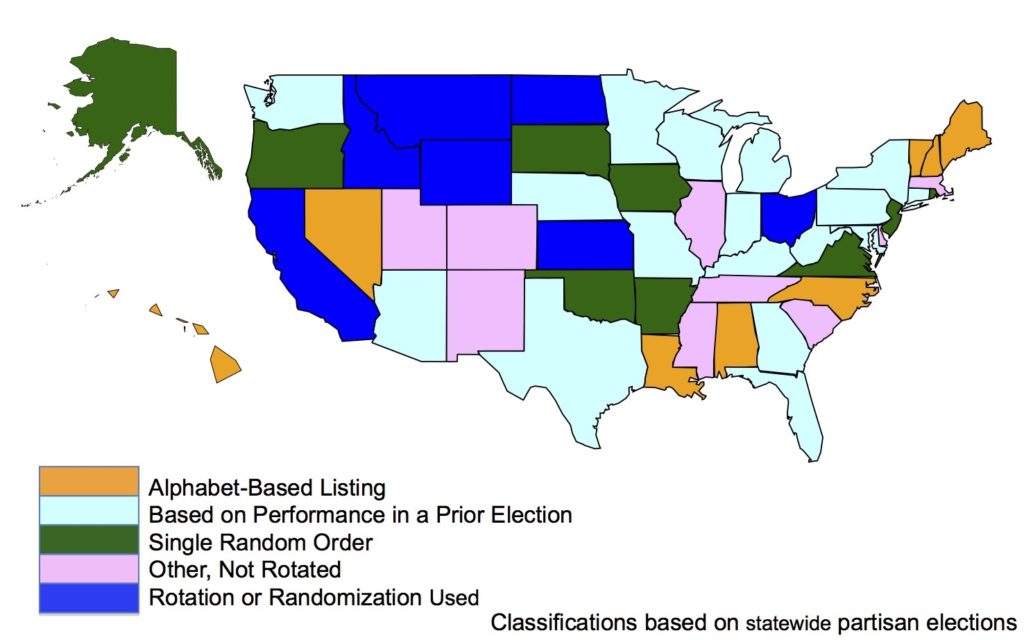

How broadly is this first-position benefit a problem? Across the country, only seven states vary the order of candidate names across precincts. Another nine choose a single random order for listing candidates in each contest, but use that same order across the entire state. And the rest generally use some combination of alphabetic ordering or a listing based on who won in prior elections at the state level. Michigan’s system – prioritizing the candidate who last won the Governor’s office – is among the most common methods.

Given the control that Republicans currently hold over governorships, this bias likely helps Republicans maintain their dominance over many state legislatures. And the effects of being listed first only grow as you move down the ballot. In our study of California, we found the average benefit for a Governor was also 0.31 percent*, Senators gained 0.37 percentage points of additional votes, and candidates for other statewide offices gained an average of 0.63 percentage points.

Source: Prevalence and moderators of the candidate name-order effect evidence from statewide general elections in California Pasek J., Schneider D., Krosnick J.A., Tahk A., Ophir E., Milligan C. (2014) Public Opinion Quarterly, 78 (2) , pp. 416-439.

For a better answer, we might look to the strategy adopted by Michigan’s neighbor to the South. Ohio produces a unique ballot for each precinct where the ordering of candidates’ names is rotated. Although it is too late to prevent this effect from altering the 2016 election, it may have less of an impact if everyone were not filling out ballots with the same candidates listed first.

*this would likely be larger if California did not elect its Governors in non-presidential years.

And that’s why down ballot races are just as important as the presidential, including the state legislature, which determines election districts.