Jul 23, 2019 | Innovative Methodology, Policy, Profile, Race, Social Policy, Uncategorized

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo

Feelings of belonging are powerfully important. A sense of inclusion in a group or society can motivate new attitudes and actions. The idea of belonging, or attaining inclusion, is the centerpiece of Angela Ocampo’s research. Her dissertation exploring the effect of inclusion on political participation among Latinos will receive the American Political Science Association’s (APSA) Race and Ethnic Politics Section’s award for the best dissertation in the field at the Fall 2019 APSA meetings.

Dissertation and Book Project

Dr. Ocampo’s dissertation grounds the theory of belonging and political participation within the literature. This research, which she is expanding into a book, finds that feelings of belonging in American society strongly predict higher levels of political engagement among Latinos. This concept represents the intersection of political science and political psychology. Dr. Ocampo draws from psychology research that belonging is a human need; people need to feel that they are a part of a group in order to succeed and have positive individual outcomes, as well as group outcomes. She builds on these psychological concepts to develop this theory of social belonging in the national community, and how this influences the perception of relationship to the polity.

The book will explore the social inclusion of racial and ethnic minorities, and how that shapes the way they participate in politics. Dr. Ocampo argues that the idea of perceiving that you belong, and the extent to which others accept you, has an influence on your political engagement and opinion of policies. For the most part, Dr. Ocampo looks at Latinos in the US, but the framework is applicable to other racial and ethnic groups. She is also collecting data among Asian Americans, African Americans, and American Muslims to look at perceived belonging.

Methodological Expertise

Before she began this research, there were no measures to capture data on belonging in existing surveys. Dr. Ocampo validated new measures and tested and replicated them in the 2016 collaborative multiracial postelection survey.

While observational data is useful for finding correlations, it can’t identify causality. For this reason, experiments also inform Dr. Ocampo’s research. In one experiment, she randomly assigned people to a number of different conditions. Subjects assigned to the negative condition showed a significant decrease in their perceptions of belonging. However, among those assigned to the positive condition, there were no corresponding positive results. In both the observational data and experiments, Dr. Ocampo notes that experiences of discrimination are highly influential and highly determinant of feelings of belonging. That is, the more experiences of discrimination you’ve had in the past, the less likely you are to feel that you belong.

Doing qualitative research has taught Dr. Ocampo the importance of speaking with her research subjects. “It’s not until you get out and talk to people running for office and making things happen that you understand how politics works for everyday people. That’s why the qualitative data and survey work are really important,” she says. By leveraging both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, Dr. Ocampo is able to arrive at more robust conclusions.

A Sense of Belonging in the Academic Community

Starting in the Fall of 2020, Dr. Ocampo will be an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Faculty Associate of the Center for Political Studies. She says that the fact that her work is deeply personal to her is what keeps her engaged. As an immigrant herself, Dr. Ocampo says, “I’m doing this for my family. I’m in this for other young women and women of color, other first-generation scholars. When they see me give a class or a lecture, they know they can do it, too.”

Dr. Ocampo is known as a supportive member of her academic community. She says it’s an important part of her work: “The reason it’s important is that I wouldn’t be here if it wouldn’t have been for others who opened doors, were supportive, were willing to believe in me. They were willing to amplify my voice in spaces where I couldn’t be, or where I wasn’t, or where I didn’t even know they were there.” She notes that in order to improve the profession and make it a more diverse and welcoming place where scholars thrive, academics have to take it upon themselves to be inclusive.

Jan 15, 2019 | Current Events, National, Race, Uncategorized

Post developed by Morgan Sherburne for Michigan News.

White conservatives who not only have racial animus but are also knowledgeable about politics were the most likely group to believe that former President Barack Obama was not born in the United States, according to a University of Michigan Institute for Social Research study.

Michael Traugott and Ashley Jardina

The study, published in the Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, teased out motivations of white voters for believing the so-called birther rumor. It found that white conservatives who ranked as having a high amount of knowledge were most likely to support the idea that Obama was not born in the U.S.

“This is a piece of social science research about biased perceptions in the political world and what their consequences might be,” said the study’s co-author Michael Traugott, a researcher at the Center for Political Studies at ISR. “It’s relevant because the whole concept of fake news is about devaluing information that doesn’t conform to either what you believe or what you want other people to believe, therefore suggesting a basis upon which it can be discounted or thrown away.”

Traugott and co-author Ashley Jardina, a former U-M doctoral student and now an assistant professor of political science at Duke University, say politically knowledgeable conservatives may be more likely to believe the rumor because they may follow what’s called a “motivated reasoning model.”

“One of the most interesting things about the motivated reasoning model is that the more resources the person has—which could be political information—the better they are able to argue against new information that doesn’t fit their worldview,” said Traugott.

Traugott and Jardina explored a portrait of a birther among white Americans using data from the 2012 American National Election Study. The ANES, conducted in person among a nationally representative sample of respondents, asked several questions assessing belief in contemporary conspiracy theories.

As recently as 2017, nearly a third of U.S. adults believed it was possible Obama was born outside the U.S., according to the researchers.

The survey also assessed participants’ knowledge by asking them to identify the office held by several political figures. A respondent’s score on the scale was the proportion of correctly answered questions.

The researchers found that 62 percent of very strong Republicans reported that Obama was born in the U.S. compared to 89 percent of very strong Democrats. Thirty-eight percent of very strong Republicans reported that Obama was probably born in another country, while 11 percent of very strong Democrats reported the same.

To estimate the impact of racial attitudes on the birther rumor, the researchers compared two conspiracy theories detailed in the 2012 ANES survey: the Obama birther rumor and the existence of the Affordable Care Act “death panels,” or, the idea that the ACA authorized government panels to make end-of-life decisions for people on Medicare.

Additionally, the researchers found:

- Strong Republicans with higher levels of racial animus are more inclined to believe the birther rumor, but not the death panel rumor.

- Republicans both low on resentment and low on knowledge are also more inclined to believe the birther rumor.

- Democrats with higher levels of racial resentment are not significantly inclined to adopt either rumor.

- Democrats low on knowledge and high on resentment are more likely to adopt birther beliefs.

- High-knowledge Democrats with high levels of racial resentment are less likely to believe the rumor.

“Until recently, the relationship of party identification to things like voting behavior had weakened, but it has strengthened again,” Traugott said. “We expected partisanship would play a role in attitudes about Barack Obama, and because he was an African American, racial attitudes would play a role as well. These things are now increasingly important because of this kind of tribalism that’s infecting contemporary politics.”

More information:

Dec 17, 2018 | ANES, APSA, Elections, Gender, International, National, Policy, Race

Post developed by Katherine Pearson

Since its establishment in 2013, a total of 146 posts have appeared on the Center for Political Studies (CPS) Blog. As we approach the new year, we look back at 2018’s most-viewed recent posts. Listed below are the recent posts that you found most interesting on the blog this year.

Crime in Sweden: What the Data Tell Us

By Christopher Fariss and Kristine Eck (2017)

Debate persists inside and outside of Sweden regarding the relationship between immigrants and crime in Sweden. But what can the data actually tell us? Shouldn’t it be able to identify the pattern between the number of crimes committed in Sweden and the proportion of those crimes committed by immigrants? The answer is complicated by the manner in which the information about crime is collected and catalogued. This is not just an issue for Sweden but any country interested in providing security to its citizens. Ultimately though, there is no information that supports the claim that Sweden is experiencing an “epidemic.”

Read the full post here.

Exploring the Tone of the 2016 Campaign

Exploring the Tone of the 2016 Campaign

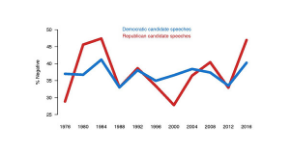

By undergraduate students Megan Bayagich, Laura Cohen, Lauren Farfel, Andrew Krowitz, Emily Kuchman, Sarah Lindenberg, Natalie Sochacki, and Hannah Suh, and their professor Stuart Soroka, all from the University of Michigan. (2017)

The 2016 election campaign seems to many to have been one of the most negative campaigns in recent history. The authors explore negativity in the campaign – focused on debate transcripts and Facebook-distributed news content – and share their observations.

Read the full post here.

Attitudes Toward Gender Roles Shape Support for Family Leave Policies

Attitudes Toward Gender Roles Shape Support for Family Leave Policies

By Solmaz Spence (2017)

In almost half of two-parent households in the United States, both parents work full-time. Yet when a baby is born, it is still new moms who take the most time off work. On average, new mothers take 11 weeks off work while new dads take just one week, according to a 2016 survey carried out by the Pew Research Center. In part, that is because many new fathers in the U.S. don’t have access to paid paternity leave. Paid maternity leave is rare, too: in fact, the U.S. is the only developed nation that does not provide a national paid family leave program to new parents.

Read the full post here.

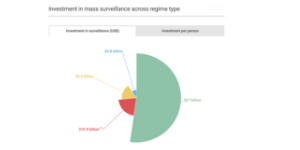

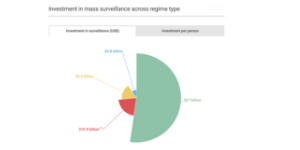

The Spread of Mass Surveillance, 1995 to Present

The Spread of Mass Surveillance, 1995 to Present

By Nadiya Kostyuk and Muzammil M. Hussain (2017)

By closely investigating all known cases of state-backed cross-sector surveillance collaborations, the authors’ findings demonstrate that the deployment of mass surveillance systems by states has been globally increasing throughout the last twenty years. More importantly, from 2006-2010 to present, states have uniformly doubled their surveillance investments compared with the previous decade.

Read the full post here.

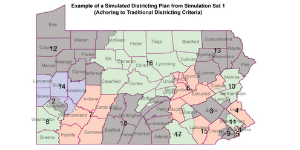

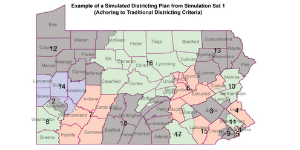

Redrawing the Map: How Jowei Chen is Measuring Partisan Gerrymandering

Redrawing the Map: How Jowei Chen is Measuring Partisan Gerrymandering

By Solmaz Spence (2018)

“Gerrymandering”— when legislative maps are drawn to the advantage of one party over the other during redistricting—received its name in 1812, when Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry signed off on a misshapen district that was said to resemble a salamander, which a newspaper dubbed a “gerrymander.”

But although the idea of gerrymandering has been around for a while, proving that a state’s legislature has deliberately skewed district lines to benefit one political party remains challenging.

Read the full post here.

Inside the American Electorate: The 2016 ANES Time Series Study

Inside the American Electorate: The 2016 ANES Time Series Study

By Catherine Allen-West, Megan Bayagich, and Ted Brader (2017)

Since 1948, the ANES- a collaborative project between the University of Michigan and Stanford University- has conducted benchmark election surveys on voting, public opinion, and political participation. To learn more about the study, we asked Ted Brader (University of Michigan professor of political science and one of the project’s principal investigators) a few questions about the anticipated release.

Read the full post here.

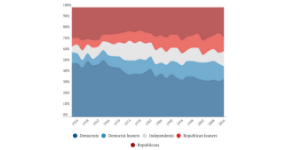

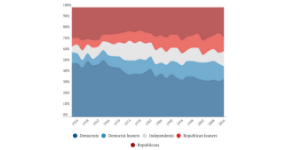

Understanding the Changing American Electorate

Understanding the Changing American Electorate

By Catherine Allen-West (2018)

The American National Election Studies (ANES) has surveyed American citizens before and after every presidential election since 1948. The survey provides the public with a rigorous, non-partisan scientific basis for studying change over time in American politics.

The interactive graphs in this post illustrate the changing American electorate and some of the factors that may motivate voters’ choices at the ballot box.

Read the full post here.

Using Twitter to Observe Election Incidents in the United States

Using Twitter to Observe Election Incidents in the United States

By Catherine Allen-West (2017)

Election forensics is the field devoted to using statistical methods to determine whether the results of an election accurately reflect the intentions of the electors. Problems in elections that are not due to fraud may stem from legal or administrative decisions. Some examples of concerns that may distort turnout or vote choice data are long wait times, crowded polling place conditions, bad ballot design and location of polling stations relative to population.

Read the full post here.

Inequality is Always in the Room: Language and Power in Deliberative Democracy

Inequality is Always in the Room: Language and Power in Deliberative Democracy

By Catherine Allen-West (2017)

In a paper presented at the 2017 APSA meeting, Arthur Lupia, University of Michigan, and Anne Norton, University of Pennsylvania, explore the effectiveness of deliberative democracy by examining the foundational communicative acts that take place during deliberation.

Read the full post here.

Making Education Work for the Poor: The Potential of Children’s Savings Accounts

Making Education Work for the Poor: The Potential of Children’s Savings Accounts

By Katherine Pearson (2018)

Dr. William Elliott contends that we need a revolution in the way we finance college education. His new book Making Education Work for the Poor, written with Melinda Lewis, takes a hard look at the inequalities in access to education, and how these inequalities are threatening the American dream. Elliott and Lewis present data and analyses outlining problems plaguing the system of student loans, while also proposing children’s savings accounts as a robust solution to rising college costs, skyrocketing debt burdens, and growing wealth inequality. In a presentation at the University of Michigan on October 3, 2018, Elliott presented new research supporting the case for children’s savings accounts and rewards card programs.

Read the full post here.

Sep 1, 2018 | APSA, Elections, Race

By Nicholas Valentino, James Newburg and Fabian Neuner

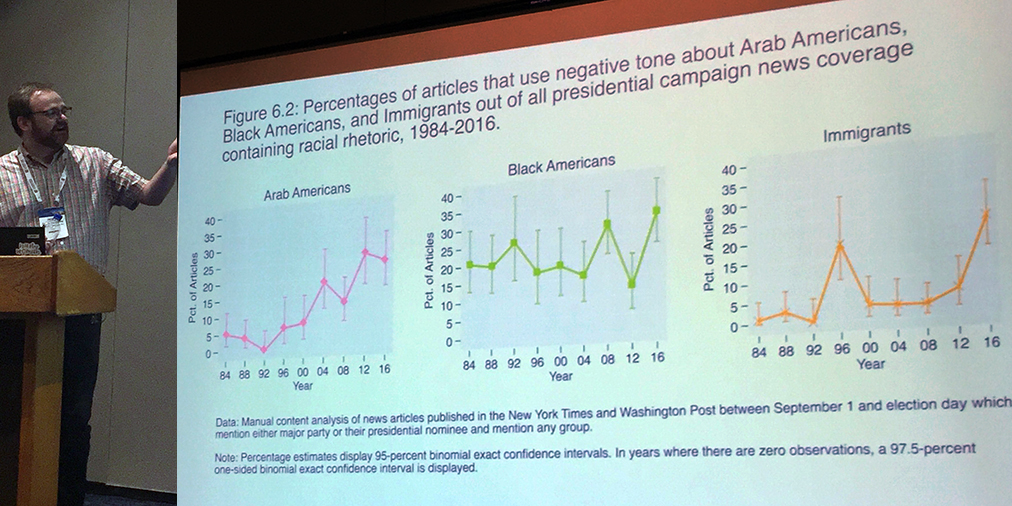

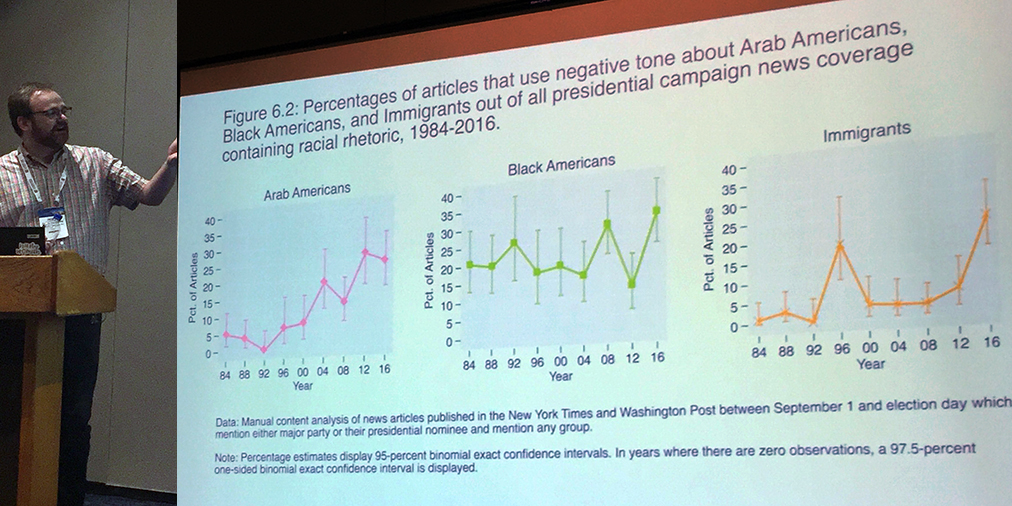

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “Dog Whistles to Bullhorns: Racial Rhetoric in Presidential Campaigns, 1984-2016” was a part of the session “Framing Politics: The Importance of Tone and Racial Rhetoric for Framing Effects” on Friday, August 31, 2018.

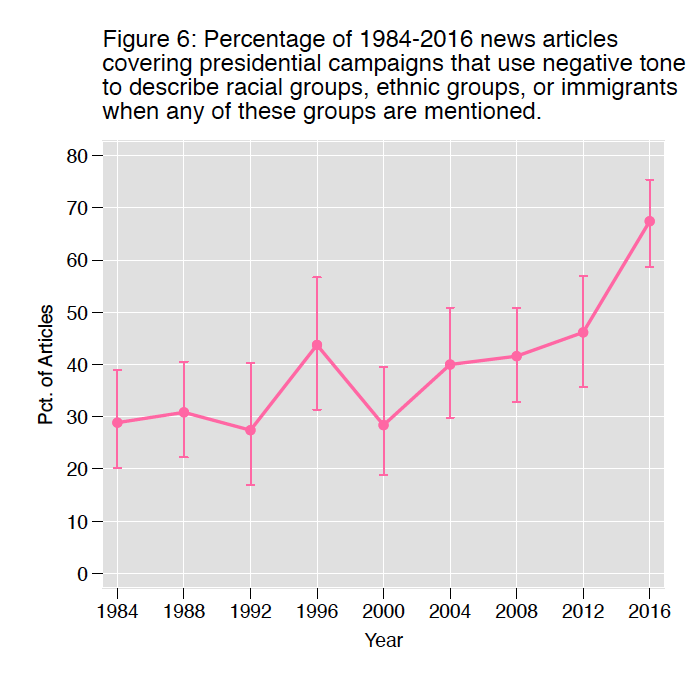

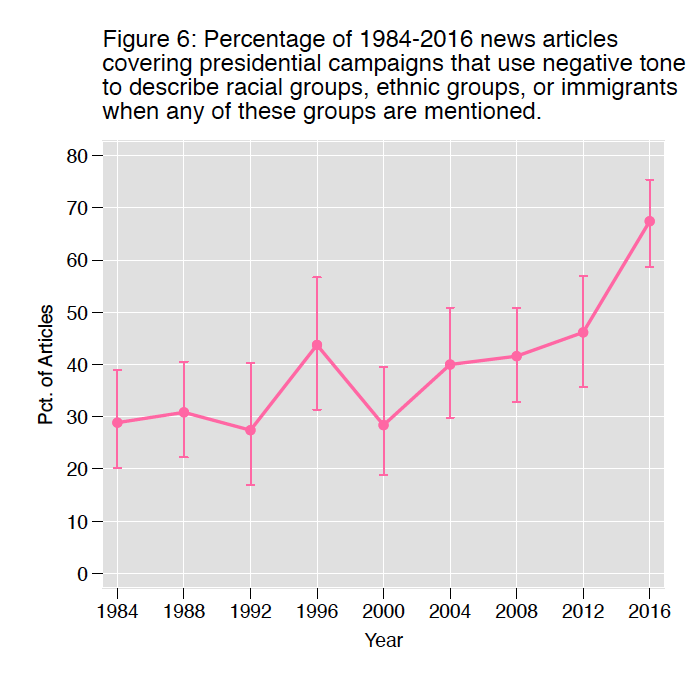

Political candidates’ use of coded language to express controversial attitudes on race is nothing new – but is it more common than in the past? Nicholas Valentino, James Newburg, and Fabian Neuner analyzed data from 1984 to the present that showed campaign rhetoric in 2016 included more racial rhetoric, negative racial group outreach, and negative mentions of racial groups than any other campaign they studied.

Beginning in 1968 through the late 1990s, the expression of explicitly racist attitudes seemed to be in decline, although racially charged imagery was still used in the news and media. While the rhetoric became subtler, prejudicial attitudes were still expressed through “racially coded” language. Over time, issues like crime, welfare, and immigration evoked negative racial stereotypes that could impact political choices without explicitly mentioning race.

Beginning in 1968 through the late 1990s, the expression of explicitly racist attitudes seemed to be in decline, although racially charged imagery was still used in the news and media. While the rhetoric became subtler, prejudicial attitudes were still expressed through “racially coded” language. Over time, issues like crime, welfare, and immigration evoked negative racial stereotypes that could impact political choices without explicitly mentioning race.

The shift to less directly rhetoric is important because implicit references to race and racial stereotypes may have a greater impact on perceptions than explicit ones do. The authors of this study note that previous research shows that people may dismiss obvious appeals to racial bias, while actually being influenced by more subtle or coded language. They note that the strength of this effect is uncertain, and that recent studies show respondents more likely to accept explicit racial rhetoric.

After Barack Obama’s election in 2008, racially charged discourse became more explicit, shocking some Americans. It was impossible not to notice the change in the tone of racial language in the election of 2016. But when exactly did this shift occur? Did it happen gradually or all at once?

To answer these questions, the authors examine trends in racial rhetoric reported in the news between 1984 and 2016. They set out a hypothesis: If changes in rhetoric happened more gradually over time as a result of partisan realignment, they should see trends in the use of explicit racial rhetoric that predate the 2016 campaign, and perhaps even prior to 2008. If, on the other hand, the 2016 election and the candidacy of Donald Trump is the major cause of shifts in discussions of race and ethnicity in mainstream American politics, they would expect explicit group mentions, especially hostile ones, to spike in 2016.

The researchers conducted a rigorous analysis of thousands of articles published in the New York Times and Washington Post between September 1 and Election Day during every presidential election year from 1984 to 2016. They found that while mentions of race were high throughout the study period, racial rhetoric spiked in 2016, especially with regard to immigrants and immigration.

Significant moments of presidential campaigns track with the rise and fall of explicit mentions of race in the news. As Republicans made electoral gains among Southern Whites, racial language reached a peak; during the more moderate campaigns of Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, racial language declined. Race became more prominent with the historic election of Barack Obama in 2008, but declined when Obama avoided discussions of race during his reelection campaign. The authors find that 2016 was unique in the high number of explicitly negative racial statements, but that partisan realignment had been causing this change had also been driving up the acceptability of these types of messages over several years.

They found that while the total amount of group coverage did not rise sharply until 2016, the coverage that was dedicated to groups got more negative gradually over time. Notably, an important factor in the secular increase of racial rhetoric was negative language describing Arab Americans, Latinos, and Immigrants in recent years. As American demographics continue to change and non-white groups grow in numbers and political strength, these trends in political language will grow even more significant.

Nov 30, 2017 | Current Events, Elections, Michigan, Race, Student Experiences

Post developed by Mara Ostfeld and Catherine Allen-West

The effectiveness of America’s system of democratic representation, in practice, turns on broad participation. Yet only about 60 percent of voting eligible Americans cast their vote in presidential elections. This number is nearly cut in half in off-year elections (about 36 percent), and participation in local elections is even lower. This lack of electoral engagement does not fall equally across racial and ethnic subgroups. Latinos, for one, are particularly underrepresented at polling booths across the country. In 2016, eligible Latino voters were about 20 percentage points less likely to vote than their White counterparts, and about 13 percentage points less likely to vote than their Black counterparts.

This fall, a group of 24 University of Michigan undergraduate students sought to explore this disparity and pinpoint what, if anything, works to increase Latino political participation. In the class, entitled The Politics of Latinidad, CPS Faculty Associate and U-M Political Science Professor Mara Ostfeld taught her students how to measure public opinion and challenged them to analyze the factors that affect Latino political participation.

Today, more than 50,000 Latinos live in Detroit and a majority of them reside in City Council District 6 in Southwest Detroit which is precisely where this course focused. The students began by studying the history of Latinos in Southeast Michigan and exploring how Latinos played critical roles in the city’s development dating back to before World War I. They analyzed broad trends in Latino public opinion, and considered how and why these patterns might be similar or different in Detroit. Students then designed their own pre-election polls to take into the field.

In order to understand what affects voter turnout, students surveyed over 300 residents of Southwest Detroit to measure the issues that were most important to them.

Students pictured here: Storm Boehlke, Mohamad Zawahra, Alex Tabet , Hannel So, Sion Lee.

The results illustrate some powerful patterns. Among the issues that the residents found most important, immigration and crime stood out. Forty-nine and 45 percent of Latinos listed immigration and crime, respectively, as issues of particular concern, with only 31 percent of residents saying that they felt safe in their own home.

Latinos in Southwest Detroit feel extremely high levels of discrimination. Seventy percent of Latinos surveyed said they felt Latinos face “a great deal” of discrimination. This significantly exceeds the roughly half of Latinos nationwide who say they have experienced discrimination.

Student Alex Garcia visits residents in Detroit.

Local issues were also at the forefront of residents’ minds. Latinos had mixed views on the city’s use of blight tickets to combat housing code violations, with one third of respondents supporting them and one third opposing them.

As local organizations, like Michigan United, continue trying to get a paid sick leave initiative on the ballot in 2018, they can expect strong support among Latinos in Southwest Detroit. About two out of every three Latinos in the area indicated they would be more likely to support a candidate who supports the paid sick leave requirement.

The students then followed up with the residents a month later to see if they planned to vote in the upcoming city council election. At this point, the students implemented some interventions that have been used to increase political participation like, evoking emotions that have been shown to have a mobilizing effect, framing voting as an important social norm, and speaking with voters immediately before an election. With the election now over, students are back in the classroom analyzing the effectiveness of these interventions and will use their first-hand experience to better understand public opinion and political participation.

Nov 15, 2017 | APSA, Foreign Affairs, Race, Social Policy

Post developed by Catherine Allen-West

There is a long, documented history of large opinion gaps along racial/ethnic lines regarding U.S. military intervention and humanitarian assistance. For example, some research suggests that since minorities are most likely to bear the human costs of war, African Americans and Latinos might be more strongly opposed to foreign intervention. Additionally, research conducted during the Iraq war found that the majority of African Americans didn’t support the war effort because they believed that they would be the ones called upon to do the “fighting and dying” and that the war would tie up resources typically used for domestic social welfare programs, programs upon which the group depends.

One obvious explanation for these opinion gaps is simple group interest. Americans are more likely to intervene to protect the lives and human rights of victims of humanitarian crises or genocides when the victims are “like us” and this narrow racial or ethnic group interest may be what drives racial/ethnic differences in support for foreign intervention or immigration policy in the U.S. This is important because public support for military and humanitarian interventions is crucial to not only the quantity of aid but also its quality and effectiveness.

But this simple in-group, material interest explanation doesn’t always hold up empirically. African Americans were more protective of the rights of Arab Americans after 9/11, even though they perceived themselves to be at higher risk from terrorism.

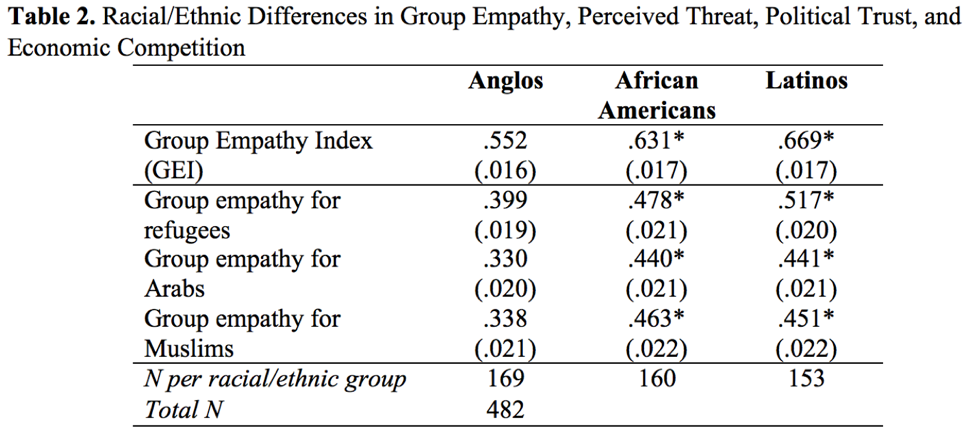

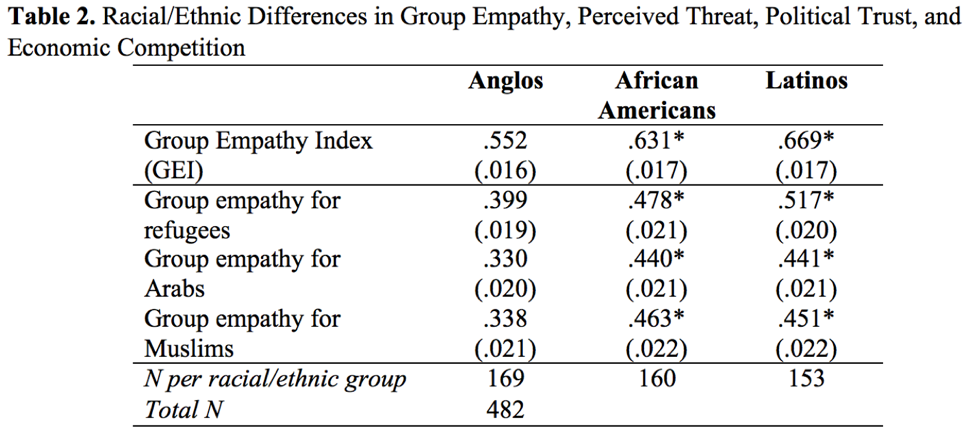

In a new paper, presented at the 2017 APSA annual meeting, Cigdem V. Sirin, Nicholas A. Valentino, and José D. Villalobos examine variations in political attitudes across three main racial/ethnic groups — Anglos, African Americans, and Latinos — regarding humanitarian emergencies abroad. The researchers tested these differences using their recently developed “Group Empathy Theory” which states that “empathy felt by members of one group for another can improve group-based political attitudes and behavior even in the face of material and security concerns.” Essentially, the researchers predict that a domestic minority group can empathize with an international group experiencing hardship, even when the conflict doesn’t involve the domestic group at all and when extending help oversees is costly.

The researchers tested their theory with a national survey experiment that assessed support for pre-existing foreign policy attitudes about the U.S. responsibility to protect, foreign aid, the U.S. response to the Syrian civil war, as well as the Muslim Ban proposed by Donald J. Trump.

First, they measured levels of group empathy and found that African Americans and Latinos both display significantly higher levels of general group empathy and support for foreign groups in need.

Next, to measure opinions about the U.S. ability to protect, they provided participants with a pair of statements about the role the U.S. should plan in international politics. The first statement read: “As the leader of the world, the U.S. has a responsibility to help people from other countries in need, especially in cases of war and natural disasters.” The second statement was the opposite — denouncing such responsibility to protect. Their results show that African Americans and Latinos are likely to attribute the U.S. higher responsibility to protect people of other countries in need as compared to Anglos. Furthermore, when asked about their opinion on the amount of foreign aid allocated to help countries in need, Latinos and African Americans were more strongly in favor of increasing foreign aid and accepting Syrian refugees than were Anglos.

The researchers further examined potential group-based difference in policy attitudes regarding Trump’s controversial “Muslim ban” which called for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States. Again, both Latinos and African Americans exhibited significantly higher opposition than Anglos to the exclusionary policy targeting a specific group solely based on that group’s religion.

Further analyses also supported the researchers’ claims that group empathy is a significant mediator of these racial gaps in support for humanitarian aid and military intervention on behalf of oppressed groups oversees.

This research brings into focus some of the dynamics that shape public opinion of foreign policy. Given the role of the public in steering U.S. leadership decisions, especially as the current administration seeks to implement deep cuts to foreign aid, investigating the role that group empathy plays in public responses to humanitarian emergencies has important broader implications, particularly concerning U.S. foreign policy and national security.

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo

Post developed by Katherine Pearson and Angela Ocampo

Exploring the Tone of the 2016 Campaign

Exploring the Tone of the 2016 Campaign Attitudes Toward Gender Roles Shape Support for Family Leave Policies

Attitudes Toward Gender Roles Shape Support for Family Leave Policies

Inequality is Always in the Room: Language and Power in Deliberative Democracy

Inequality is Always in the Room: Language and Power in Deliberative Democracy