Nov 21, 2014 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Written by William Foreman for Global Michigan. Reblogged here with permission.

Pro-Russian militants in Eastern Ukraine. (Credit: VOA)

As the conflict grinds on in Ukraine, there are more questions about Russia’s intentions, the effectiveness of sanctions and what the West can do to end the fighting. These issues were discussed in a Global Michigan interview with Yuri Zhukov.

Zhukov is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Michigan and a faculty associate at the Center for Political Studies. His expertise is in international and civil conflicts.

Yuri Zhukov

The scholar has several projects ongoing on the fighting in East Ukraine. He’s interested in rebel movements in the region, the economics behind the conflict, military operations and the “information war” in the Russian and Ukrainian media. He recently wrote a piece for Foreign Affairs.

What is Russia up to now?

Zhukov: Last week, NATO accused Russia of sending tanks and artillery into Ukraine, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe reported seeing a column of unmarked military trucks heading toward Donetsk. Russia denies these claims, and accuses Ukraine of concentrating its own forces near the front line. In fact, both sides of the conflict have been steadily ratcheting up tensions since elections this fall, in government and separatist-controlled areas of Ukraine. The outcome in each election simply reinforced the status quo, but both sides may now feel they have a stronger mandate to take bold steps.

Are the reported troop movements into Ukraine part of a plan to create a land bridge with Crimea or annex more of the country?

Zhukov: These troop movements are not large enough to take significant territory outside rebel-held areas in Donetsk and Luhansk. They are more likely reinforcements for rebel units fighting in Donetsk airport and other contested areas and a deterrent against sudden moves by Ukraine.

Are the sanctions helping or hurting Russian President Vladimir Putin?

Zhukov: In the short term, the sanctions may have created a “rally-around-the-flag” effect, which boosts Putin’s domestic popularity. But historically, Putin has owed much of his popularity to perceptions of sound economic management. Russian consumers are seeing higher food prices, and the ruble has lost over a third of its value since the crisis began. Putin’s poll numbers are still high, but beginning to fall.

If the fighting escalates, should the U.S. and EU provide arms to Ukraine?

Zhukov: Some countries have already provided military aid, on a bilateral basis, most of it nonlethal. The larger question is whether Western military aid can actually change the military balance of power on the ground. Russia will surely see such a policy as a major provocation and will respond in kind. This could trigger an arms race along the lines we have seen in Syria, with increasing flows of weapons and fighters to both sides. This is also a commitment that the West would need to sustain for some time. Major military aid may deter rebels from taking more ground but is unlikely to reverse existing rebel gains in the near future.

Should there be more sanctions?

Zhukov: It depends. Some types of sanctions—like freezing the assets of wealthy Russians in Europe—actually align with Putin’s policy goal of “de-offshorization.” Anything that makes it more difficult for powerful Russians to park their money abroad is a win for Putin. Some of the new measures currently on the table—like blocking Russian banks and businesses from the SWIFT financial transaction system—will have bigger impact.

Sanctions can and are already hurting Russia’s economy. Whether they can also change the course of the Ukrainian conflict is a different matter. There is no “magic switch” that Putin can press to stop the fighting. The rebel high command has been replaced by a cadre of more professional, manageable leaders, but the rebellion as a whole is still a diverse, fractious lot. Many rival militias are looking to carve a place for themselves in the new “Peoples’ Republics,” and quite a few locals feel betrayed that Russia did not intervene more forcefully. Sanctions are unlikely to change the decision calculus of these actors.

What more can the West do?

Zhukov: The West has limited options, and many of them—like military aid, alliance commitments to Ukraine, even sanctions—are more likely to escalate the conflict than stop it. Russia has made clear that it is ready to intervene if the tide of the war turns decisively against the rebels—as it did, temporarily, in August this year. Any future steps—in Kyiv or the West—will take place against the background of this latent threat of force. What’s worse, the terms of the current ceasefire agreement are suboptimal for all parties. Rebel leaders want to eliminate pockets of government forces and create a more contiguous, governable territory. The Ukrainian president is under pressure from hard line elements in the government to take bolder action. The best course of action for the U.S. is to tread carefully, and do everything possible to restrain both sides.

Nov 19, 2014 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and David A. Lake.

ISIL (a.k.a. ISIS, a.k.a. Da’ish) in Syria and Iraq. Al-Shabaab in Somalia. Boko Haram in Nigeria. Al-Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan. All of these insurgent groups have risen to power in failed states, or “ungoverned spaces.” Can we fix these failed spaces?

David A. Lake, Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of California San Diego and Director of the Yankelovich Center for Social Science Research, addressed this question in a talk titled “The Statebuilder’s Dilemma: Legitimacy, Loyalty, and the Limits of External Intervention” at the annual Harold Jacobson Lecture in International Law which was held on October 23rd, 2014.

David A. Lake, Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of California San Diego and Director of the Yankelovich Center for Social Science Research, addressed this question in a talk titled “The Statebuilder’s Dilemma: Legitimacy, Loyalty, and the Limits of External Intervention” at the annual Harold Jacobson Lecture in International Law which was held on October 23rd, 2014.

Statebuilding seeks to bring stability to unstable regions. Typically, an outside political power, e.g., the United States, will create a new government in a volatile region. In doing so, they attempt to bring a monopoly to legitimate violence. Usually this means supporting a political leader who can build a political coalition to overcome the conflicts. Often, the statebuilder marches in, plants a stake in the ground, and declares a new order. They guarantee this order as long as the different factions honor the new regime.

Statebuilding presents challenges. First, it is very expensive, with the bulk of the cost falling on the failed state. The key to success is balancing legitimacy and loyalty, which proves to be a delicate balance. That is, the new leader must remain loyal to the statebuilder but also seem legitimate to the local population. The more interest the statebuilder has in the region, the more they will require loyalty. Statebuilding fails when the new leader balks at the loyalty. Instead, money meant to be invested in building infrastructure is diverted into building his political coalition.

With the exception of Japan and Germany post-World War II, statebuilding tends to fail. The opening examples exemplify this. So Lake poses the important question: What can be done?

Lake facetiously suggests not engaging in statebuilding as the best solution. Recognizing abstention to be unlikely, he offers a few other guidelines. First, better strategy and implementation is needed, especially around election timing and monitoring. Second, an international coalition should monitor statebuilding and the process of transferring power completely to the new state.

Oct 21, 2014 | Conflict, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Christian Davenport.

Who did what to whom in 1994 Rwanda? This is the central question driving the GenoDynamics project directed by Center for Political Studies Faculty Associate and Professor of Political Science, Christian Davenport, and former CPS affiliate and current Dean of the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia, Allan Stam.

Who did what to whom in 1994 Rwanda? This is the central question driving the GenoDynamics project directed by Center for Political Studies Faculty Associate and Professor of Political Science, Christian Davenport, and former CPS affiliate and current Dean of the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia, Allan Stam.

Last week, Davenport updated the associated website to provide new, unreleased data that the project collected, documents that can no longer be found on the topic, and new visualizations and animations of collected data.

Also added to the website was a page specifically dedicated to a recent BBC documentary, Rwanda’s Untold Story, that features the research. The documentary premiered on October 1, 2014 in Europe and is now available for viewing on the Internet. The film itself has prompted some controversy. The most vocal critics call those involved with the documentary “genocide deniers,” which by Rwanda law classifies as anyone who completely denies or seeks to “trivialize” or reduce the number of Tutsi victims declared by the government. Others have protested outside the BBC headquarters in London. Still others have praised the film for bringing forward a story that they felt was long overdue.

The GenoDynamics website features all of this criticism. But it also offers a glimpse into what the researchers found and how they found it.

Davenport and Stam knew that Rwanda 1994 was a time of wide-spread violence when they began investigating in depth in 2000. But they did not know “who was engaged in what activity at what time and at what place.” With funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the researchers content analyzed and compiled data from the Rwandan government, the International Criminal Tribunal on Rwanda (ICTR), Human Rights Watch, African Rights, and Ibuka. These sources were used to create a Bayes estimation of the number of people killed in each commune of the country for the 100 days of the genocide, civil war, reprisal killings and random violence. Davenport and Stam interviewed victims and survivors as well as perpetrators in Rwanda, and they surveyed citizens in the town of Butare. Finally, through a triangulation of information from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), a Canadian Military Satellite image, and Hutu and Tutsi military informants through the ICTR, they created variables concerning troop movement and zone of control. This allowed them to see who was responsible for killings in the different locations.

The work is controversial in many respects – including the degree of transparency involved, as Davenport and Stam are the only project that has made all relevant data publicly available – but the biggest controversy concerns how they challenge popular understanding. At present, the official story is that one million people were killed by the extremist Hutu government and the militias associated with them, with most of (and in some stories all of) the victims being Tutsi (upwards of 800,000 in some estimations). But Davenport and Stam found that in 1991 (according to the Rwandan census as well as from population projections back from the 1950s) only 500,000 Tutsis lived in Rwanda. Davenport and Stam further concluded that approximately 200,000 Tutsis were killed, as it was reported by a survivors organization that 300,000 Tutsi survived. While this number is less than the official number, it still represents the partial annihilation of the Tutsi population, which includes genocide but likely other crimes against humanity and human rights violations as well. But the estimation also changes the official story: the results of this research suggest that the majority of those killed in 1994 were in fact Hutu.

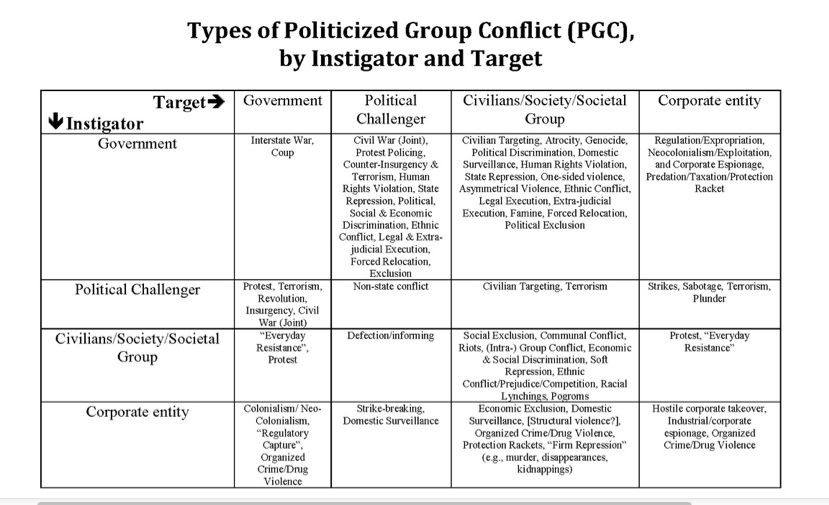

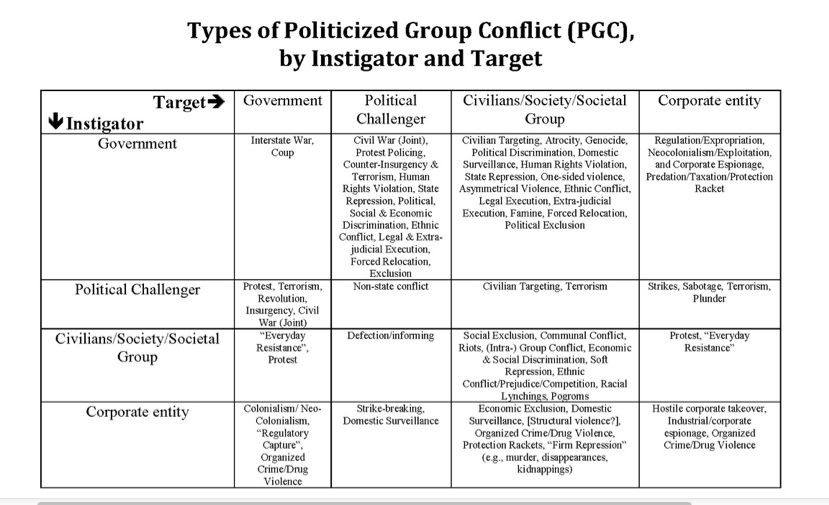

After 14 years of research, Davenport and Stam believe that there were several types of political violence occurring in Rwanda in 1994. The table below summarizes the different types of violence that were potentially involved (by perpetrator and victim). The larger project is trying to sort Rwandan political violence into each cell, which is incredibly difficult but useful for understanding exactly what happened.

The current controversy is not a new one. When Davenport and Stam presented their findings to the Rwandan government, they were told that they would not be welcome to return. When they presented their findings at the 10th and 15th anniversaries, they received more criticism. At no point was any new evidence or data provided which countered their narrative. In addition to the documentary, Davenport and Stam are working on a peer reviewed journal article and a book for a broader audience.

Sep 10, 2014 | Conflict, Current Events, Elections, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Khalil Shikaki and Mark Tessler.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

This summer witnessed intense fighting between Israel and Gaza. With tens of thousands of rockets fired, the conflict killed more than 2,000 Palestinians, mostly civilians, and 80 Israelis, mostly soldiers. How has the most recent conflict affected Palestinian attitudes?

The Palestinian Center for Policy and Research (PCPSR) conducted a survey to gauge this impact. PCPSR is run by Khalil Shikaki. This year, Shikaki is a visiting scholar at the Center for Political Studies (CPS), working closely with CPS Research Professor and expert on the Middle East Mark Tessler. In this post, we offer results from PCPSR’s study along with insight from Tessler to understand the impact of the conflict on Palestinian public opinion.

PCPSR surveyed 1,270 adults in 127 locations across the West Bank and Gaza Strip between August 26 and August 30, 2014, coinciding with the first lasting ceasefire of the conflict. Results suggest that a significant majority (79%) of the Palestinian public views Hamas as the conflict’s winner. Just 3% believe Israel emerged victorious, while 17% believe both sides lost. Likewise, 79% blame Israel for starting this wave of fighting, while 86% support launching rockets at Israel from Gaza when under attack. As for the ceasefire agreement: 63% think it satisfies Palestinian interests.

Photo credit: ThinkStock

In addition to these conflict-specific findings, the PCPSR study also finds increasing support for Hamas among Palestinians to levels not seen since 2006. If elections occurred today, current Hamas deputy political bureau chief Ismail Haniyeh would easily win a presidential race against current president Mahoud Abbas. This is a massive shift in public opinion. Tessler notes that before the most recent conflict, support for Hamas was fading. Shikaki attributes this gain to the conflict, while predicting the Hamas support may wane as time passes. Tessler likewise cautions, “If things do settle down for a reasonable period and there is a new and stable status quo, any spike in Hamas popularity will probably drift back toward its ‘normal’ level based on what people favor and perceive with respect to political Islam, compromise with Israel, corruption and other issues that drive Palestinian politics in normal times.” Thus, the lingering effects of the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict will depend on whether or not the ceasefire continues.

Khalil Shikaki will give a talk at the CPS Interdisciplinary Workshop on Politics and Policy on September 17, 2014 in Room 6006 of the Institute for Social Research in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Aug 31, 2014 | Conflict, Innovative Methodology, International

Post developed by Katie Brown and Christian Davenport.

ICYMI (In Case You Missed It), the following work was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The presentation, titled “The Domestic and/or International Determinants of State Repression: Examining Spells,” was a part of the Conflict Processes panel “Determinants of State Repression” on Sunday August 31st, 2014.

Since the Holocaust, one of the most important purported tasks of humankind has been to never again let such horrific violations of human rights occur. This mission came with a three-part strategy of preventing, stopping, and prosecuting such violations.

And yet, again and again, grave human rights violations continue to happen: Guatemala, Tibet, Rwanda, and Syria are just a few examples. Christian Davenport, Faculty Associate in the Center for Political Studies (CPS) and Professor of Political Science, along with Benjamin J. Appel of Michigan State University, have examined 220 instances of extreme state repression in recent decades.

The first analysis of its kind and part of a series which will ultimately be published in a book, the 220 examples included in the database occurred between 1976 and 2004. Each scored above a 3 on the Political Terror Scale. Level 3 is characterized by political imprisonment, including executions, no trials, indefinite sentences, and brutality. This escalates to level 4 when civil and political rights violations extend to most of the population and “murders, disappearances, and torture are a common part of life.” The scale maxes out at 5, at which point the entire population is affected by brutality, as the leader will stop at nothing to achieve ideological goals.

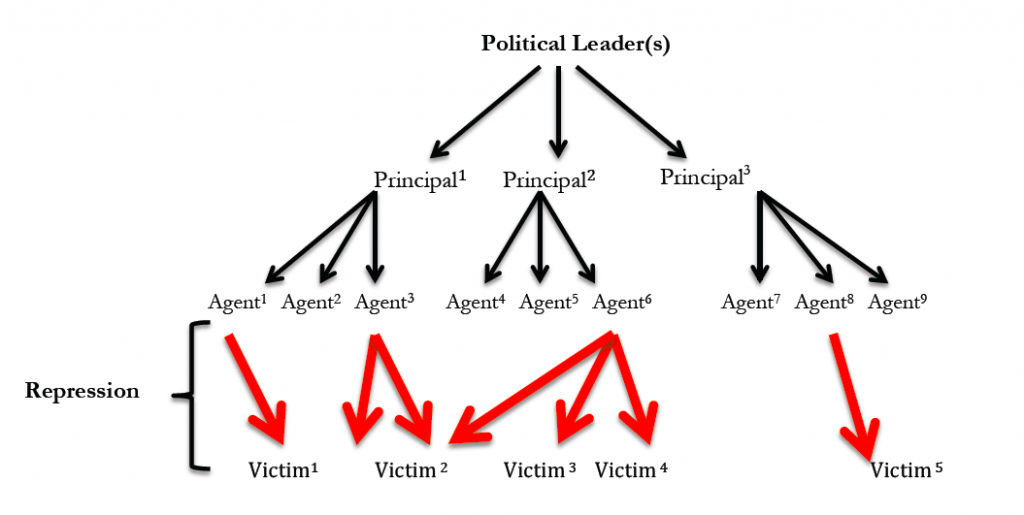

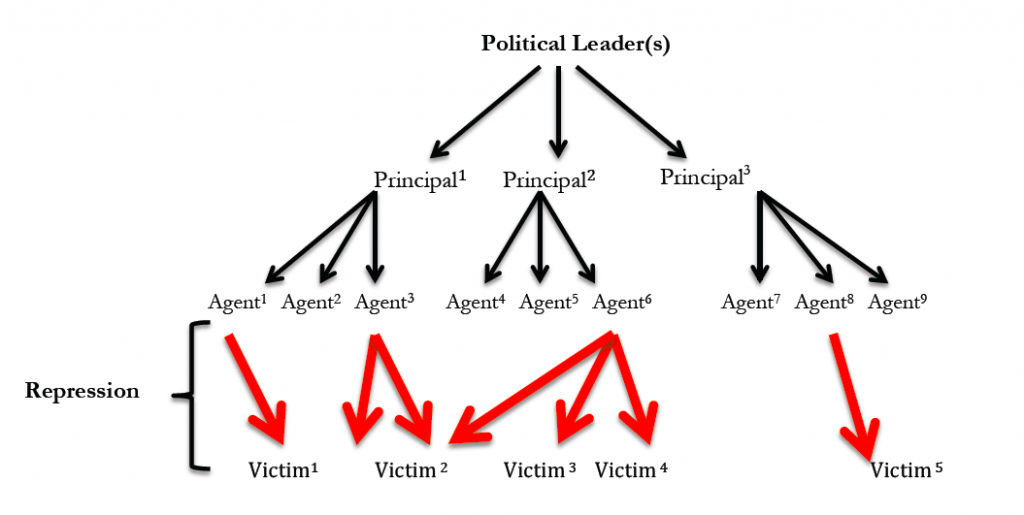

The authors clarify that, while it is the leader’s goals enacted, they do not do their own dirty work. Rather, this role is allocated to principals (e.g., generals), who in turn give the orders and necessary resources to agents (e.g., soldiers and police officers). These agents enact the brutality on victims. The flow chart below delineates this process.

Assigning the Dirty Work of State Repression

The authors’ goal in analyzing the 220 cases of state repression: understand what stops the repression. Davenport and Appel look at both domestic and international factors. International approaches include economic sanctions, military action, public condemnation, and Preferential Trade Agreements designed to make it harder for the repressive government to obtain the means of repression. Increasing democracy within the borders constitutes the domestic answer to repression.

After analyzing the 220 cases, the authors find essentially no support for the international efforts to stop repression, though Preferential Trade Agreements do exhibit an influence. The more powerful and appropriate approach, however, concerns democratization from within. The authors conclude, “If one is trying to stop state repression, then they should consider how best to move the government toward full democracy.” But, the authors caution that they best way to stop state repression is to prevent it in the first place.

Mar 5, 2014 | Conflict, Current Events, Foreign Affairs, International

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Muzammil Hussain

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In recent weeks, massive protests have swept through Venezuela and Ukraine. Instagram and Twitter have been featured as playing a key role in the latter. Digital activism is increasingly attributes to helping spark rapid waves of mobilization across several recent international cases.

Center for Political Studies (CPS) faculty associate and assistant professor of communication Muzammil Hussain studies the role of technology in protest. With Philip N. Howard of the University of Washington, Hussain published an article weighing the roles of Internet infrastructure and mobile telephony in the Arab Spring mobilizations.

Though in a different area of the world, understanding the role of communication systems, the political uses of digital media, and the politicization of internet infrastructure in the Arab Spring can help shed light on the current wave of democratization. Hussain argues that information technologies do not cause political change, but they have become a consistent tool and space to afford and act out political contentions.

To understand the relative success of the Arab Spring across different countries in the Middle East and North Africa, the authors look at a variety of contextual factors, including income, wealth distribution, unemployment, demographics, digital connectivity, censorship, and economic dependence on fuel. In the article, they examine the impact of these factors on regime fragility and social movement success. Interestingly, they argue that the inciting incidents in each country were digitally mediated. The describe how digital communication sets off a six-stage process of political mobilization experienced in both successful and failed attempts for regime change.

The authors conclude that “information infrastructure – especially mobile phone use – consistently appears as one of the key ingredients in parsimonious models for the conjoined combinations of causes behind regime fragility and social movement success.” That is, digital communication networks, especially mobile phones, drive political upheaval. In addition to offering insight into the Arab Spring experiences, this may also help explain the recent successful ousting of Ukraine’s president.