Post developed by Katie Brown and Christian Davenport.

Who did what to whom in 1994 Rwanda? This is the central question driving the GenoDynamics project directed by Center for Political Studies Faculty Associate and Professor of Political Science, Christian Davenport, and former CPS affiliate and current Dean of the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia, Allan Stam.

Who did what to whom in 1994 Rwanda? This is the central question driving the GenoDynamics project directed by Center for Political Studies Faculty Associate and Professor of Political Science, Christian Davenport, and former CPS affiliate and current Dean of the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia, Allan Stam.

Last week, Davenport updated the associated website to provide new, unreleased data that the project collected, documents that can no longer be found on the topic, and new visualizations and animations of collected data.

Also added to the website was a page specifically dedicated to a recent BBC documentary, Rwanda’s Untold Story, that features the research. The documentary premiered on October 1, 2014 in Europe and is now available for viewing on the Internet. The film itself has prompted some controversy. The most vocal critics call those involved with the documentary “genocide deniers,” which by Rwanda law classifies as anyone who completely denies or seeks to “trivialize” or reduce the number of Tutsi victims declared by the government. Others have protested outside the BBC headquarters in London. Still others have praised the film for bringing forward a story that they felt was long overdue.

The GenoDynamics website features all of this criticism. But it also offers a glimpse into what the researchers found and how they found it.

Davenport and Stam knew that Rwanda 1994 was a time of wide-spread violence when they began investigating in depth in 2000. But they did not know “who was engaged in what activity at what time and at what place.” With funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the researchers content analyzed and compiled data from the Rwandan government, the International Criminal Tribunal on Rwanda (ICTR), Human Rights Watch, African Rights, and Ibuka. These sources were used to create a Bayes estimation of the number of people killed in each commune of the country for the 100 days of the genocide, civil war, reprisal killings and random violence. Davenport and Stam interviewed victims and survivors as well as perpetrators in Rwanda, and they surveyed citizens in the town of Butare. Finally, through a triangulation of information from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), a Canadian Military Satellite image, and Hutu and Tutsi military informants through the ICTR, they created variables concerning troop movement and zone of control. This allowed them to see who was responsible for killings in the different locations.

The work is controversial in many respects – including the degree of transparency involved, as Davenport and Stam are the only project that has made all relevant data publicly available – but the biggest controversy concerns how they challenge popular understanding. At present, the official story is that one million people were killed by the extremist Hutu government and the militias associated with them, with most of (and in some stories all of) the victims being Tutsi (upwards of 800,000 in some estimations). But Davenport and Stam found that in 1991 (according to the Rwandan census as well as from population projections back from the 1950s) only 500,000 Tutsis lived in Rwanda. Davenport and Stam further concluded that approximately 200,000 Tutsis were killed, as it was reported by a survivors organization that 300,000 Tutsi survived. While this number is less than the official number, it still represents the partial annihilation of the Tutsi population, which includes genocide but likely other crimes against humanity and human rights violations as well. But the estimation also changes the official story: the results of this research suggest that the majority of those killed in 1994 were in fact Hutu.

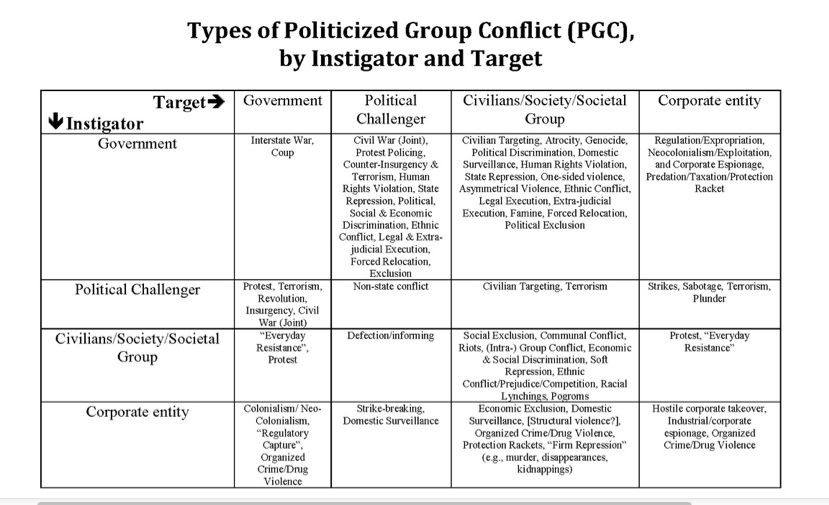

After 14 years of research, Davenport and Stam believe that there were several types of political violence occurring in Rwanda in 1994. The table below summarizes the different types of violence that were potentially involved (by perpetrator and victim). The larger project is trying to sort Rwandan political violence into each cell, which is incredibly difficult but useful for understanding exactly what happened.

The current controversy is not a new one. When Davenport and Stam presented their findings to the Rwandan government, they were told that they would not be welcome to return. When they presented their findings at the 10th and 15th anniversaries, they received more criticism. At no point was any new evidence or data provided which countered their narrative. In addition to the documentary, Davenport and Stam are working on a peer reviewed journal article and a book for a broader audience.