Jan 15, 2014 | Elections, Innovative Methodology, Michigan, National

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Arthur Lupia.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

Voters are ignorant and we must fix them. This belief has spawned much political science research and many efforts to inform the “ignorant. ” But what if this premise is false?

In a forthcoming book – The trouble with voters and those who try to fix them – Center for Political Studies (CPS) researcher and professor of political science Arthur Lupia suggests that voters aren’t as ignorant as many fear.

First, it is impossible to know all potentially relevant political information. Lupia presents his own position as a citizen as a case study. To be informed about all legislation that could affect him, Lupia should know about the more than 2,000 laws passed by the United States Senate and signed by the President. He should also know about the 40,000 additional proposed bills. As a resident of Michigan, Lupia should know about the 1,239 proposed bills, 42 concurrent resolutions, 26 joint resolutions, and 174 resolutions from the Michigan House of Representatives, as well as the 884 bills, 25 continuing resolutions, and 19 joint resolutions from the Michigan Senate in 2011 alone. Living in Ann Arbor, Lupia should also know about the many city ordinances passed in recent years. Does he know the gist, let alone the details, of each of these? No. Does he or anyone need to? No.

Second, even if you could know all potentially relevant political information, shortcuts can get you there faster. That is, voters without certain knowledge tend to vote the same as if they possessed that knowledge. Lupia likens this to traffics signals. It is impossible for a driver to know the traffic flows and locations of all vehicles in all directions when approaching an intersection. A traffic light signals the optimal time to go and stop. Voters can therefore seek out signals in a saturated, sometimes chaotic political environment to make informed choices.

So, voters are not crippled by ignorance. What then of those who try to fix voters? Lupia sees fixers as playing an integral role in civic society. But these fixers would benefit from changing their baseline assumption. Voters are not broken. With this paradigm shift in place, fixers could appeal to this group with precision and tact. To this end, Lupia offers the latest from biology and brain science, strategic communication, and marketing to help fixers better deliver their messages.

Lupia summarizes his argument in succinct terms: “From these facts alone, we can draw an important conclusion. When it comes to political information there are two groups of people. One group is almost completely ignorant of almost every detail of almost every law and policy under which they live. The other group is delusional. There is no third group.”

Nov 14, 2013 | ANES, Michigan, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown.

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In June of this year, the Supreme Court of the United States maintained the legality of affirmative action programs at American colleges and universities – for now. The Supreme Court’s seven-to-one decision pushes American colleges and universities to prove the utility of affirmative action programs. The court declined to rule specifically on a case regarding the University of Texas at Austin’s affirmative action policy. This week, the UT Austin case was debated before a federal court.

How does the American public feel about affirmative action, and has their support or opposition changed over time? The American National Election Studies (ANES) can be used to examine such trends. For 65 years, the ANES has interviewed a representative sample of voting age Americans on a variety of topics, including but not limited to voting and turnout, public policy support, societal values, and demographics. As ANES describes, the resulting data “inform the nation about itself.”

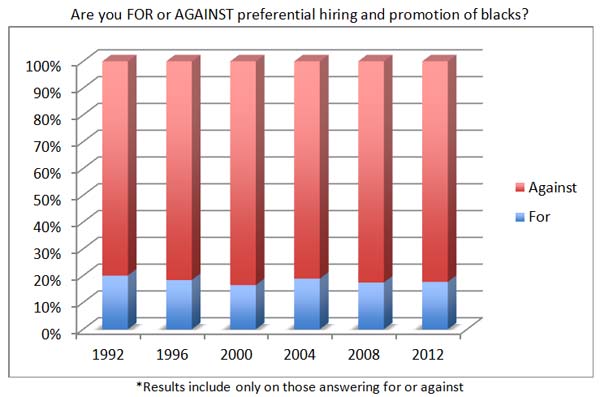

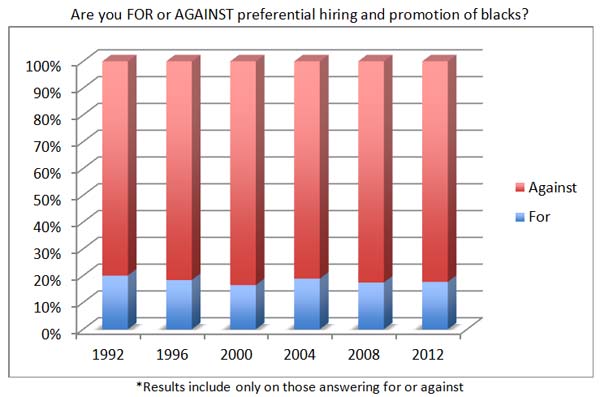

There are many ways to measure levels of support or opposition for affirmative action. Since 1992, ANES has asked the American voting age public whether it is “for or against” one type of affirmative action: preferential hiring and promotion of blacks. As the graph below illustrates, public opposition in the United States for this type of affirmative action appears both dominant and stable over the time period 1992-2012.

In 2012, ANES also asked a question about support or opposition for the use of quotas to admit black students to colleges and universities. The results were similar, with 77% of respondents opposing such a program and 23% of respondents being in support.

The latest Supreme Court ruling comes on the heels of a 2003 Supreme Court decision regarding the University of Michigan‘s use of affirmative action in its decision-making process for admitting students. The Court upheld the use of affirmative action by the University’s law school but negated the use of affirmative action in its undergraduate admissions. In 2006, voters from the state of Michigan voted in support of a ballot referendum, Proposition 2, which made affirmative action illegal in the state. Then in November of 2012, the state of Michigan’s 6th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Proposition 2. Last month, the constitutionality of Proposition 2 went before the Supreme Court of the United States.

The latest court proceedings suggest that the future of affirmative action remains unclear, but results from the ANES suggest that public opposition to affirmative action remains stable. Yet, no single question or two can encapsulate feelings toward an issue as complex as this one.

Oct 31, 2013 | Michigan, National, Social Policy

Developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Rosemary Sarri

Photo credit: Thinkstock

In June of 2013, Sesame Street debuted its first character with a parent in prison. The Sesame Street website now features a page of video clips and guides to help children facing this situation. But how likely is it a child will see his or her parent go behind bars?

The U.S. has a high rate of incarceration, about 760 per 100,000. The rates are higher than peer countries – five times the rate of Britain, and eight times the rate of Germany. But are the rates even higher for families with criminal pasts?

Center for Political Studies (CPS), School of Social Work, and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri studies social policy, with an emphasis on children in the justice system. In a paper just published with Irene Ng and Elizabeth Stoffregen in the Journal of Poverty, Sarri considers the intergenerational nature of incarceration.

The study grew from a larger effort to understand preparation of youth returning from detention to the community. Data analysis revealed high levels of parental imprisonment among the youth in the sample. So the researchers considered the issue in more depth.

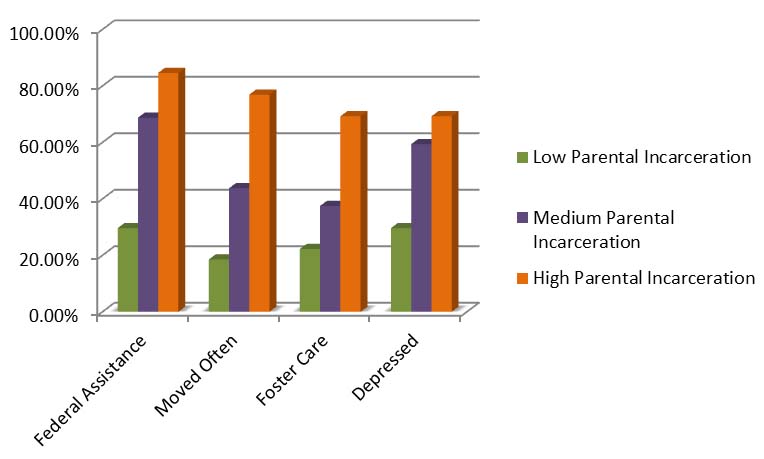

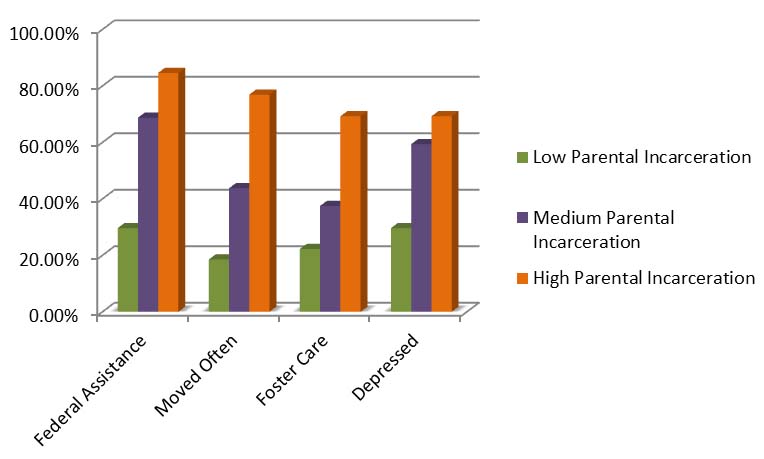

The researchers broke their participants into three groups: low, medium, and high levels of parental incarceration. Then they performed a cluster analysis to determine if these three groups varied along different factors.

The results indicate that higher levels of parental incarceration correspond to negative life events, parental substance abuse, receiving federal assistant, placement in foster care, neighborhood quality and instability, stigma, and negative youth outcomes. The graph below displays four of these associations by level of parental incarceration.

So having a parent in prison not only increases the risk of a child facing juvenile lock up, but is also associated with other negative experiences. The troubles appear to perpetuate along family trees. A staggering 53% of the juvenile offenders in the study have children themselves. Further, most of the male participants expected little future contact with their children.

It would be easy to be pessimistic given these results, but the results highlight a situation that needs to be addressed. In response, Sarri calls for a re-examination of imprisoning parents. She argues that these families and society at large could benefit from community programs that support families. Such community programs demonstrate long-term positive effects for both parents and children. When used for non-violent offenses, like drug abuse, such community programs protect public safety while potentially redirecting the growth of ill-fated family trees. Sarri also suggests parenting training, substance abuse and mental health treatment, workforce development, and community organization to relieve disorganization. These preventative services could help redirect families before there’s a problem.

Aug 13, 2013 | Michigan, National, Social Policy

Post developed by Katie Brown in coordination with Rosemary Sarri

Detroit makes headlines often: declining population, high crime rates, blocks of urban blight and, recently, the city’s declaration of bankruptcy. How does living in this bad news impact the city’s children? And, perhaps more importantly, how are we coping with the inevitable fallout this has on Detroit’s children?

Detroit makes headlines often: declining population, high crime rates, blocks of urban blight and, recently, the city’s declaration of bankruptcy. How does living in this bad news impact the city’s children? And, perhaps more importantly, how are we coping with the inevitable fallout this has on Detroit’s children?

Center for Political Studies, School of Social Work, and Women’s Studies Professor Emerita Rosemary Sarri studies the impact of social policy on children. In a forthcoming book chapter – “Juvenile Justice in a Changing Environment” – Sarri considers the developing approaches to juvenile offenders, focusing on Wayne County, Michigan, home of Detroit.

The concept of approaching juveniles in the justice system as distinct from their adult counterparts emerged just over a century ago. Two Supreme Court decisions – Roper v. Simmons in 1995 and Graham v. Florida in 2010 – reasserted the necessity of lesser sentences for youth offenders. Further, there is a large capital investment in the system. With 70,000 children in the justice system at an individual incarceration cost of $88,000 per year, the total exceeds $6 billion annually. This large amount of money coupled with the increasing emphasis on viewing children as in the midst of development shifted focus to rehabilitation over punishment. Wayne County, including Detroit, has paved the way.

In the 1990s, the state of Michigan controlled Wayne County’s youth offenders, punishing both serious and lesser crimes with long periods of detention, often out of state. U.S. Department of Justice threatened to close the in-county detention facility itself due to overcrowding and poor physical conditions, while the Michigan Auditor General issued a report criticizing the whole process. Without adequate mental health services and educational aid, recidivism – committing crimes again upon being released – topped 50%. The county and state spent $150 million per year on this ineffective program.

In the late 1990s, crime overall declined, but youth crimes associated with Detroit’s problems of homelessness, substance abuse, and gangs continued. Public outcry and political pressure to revamp the juvenile justice system was answered in 1997, when the system was overhauled.

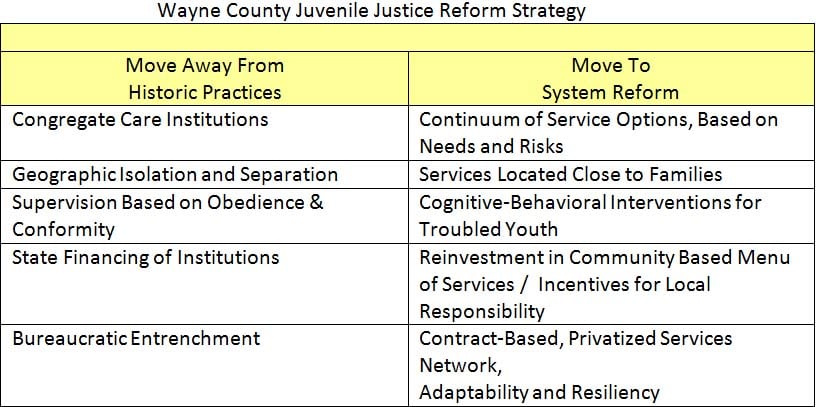

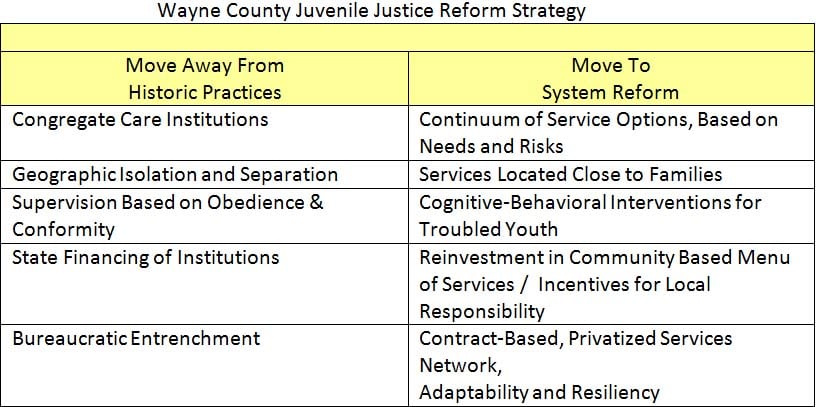

The new mission, as Sarri writes, was to, “Treat each individual as a person in need of opportunities and resources rather than one with a societal disease that needed to be contained.” Wayne County spearheaded the initiative, which emphasized mental health care, education, and alternatives to incarceration, as summarized by the table below

The information management also built into the new approach allows the effects to be quantified. In 1998, 731 youth were incarcerated. In 2012, there were six, with no juveniles placed out of state. From 2004 to 2012, the number of new delinquency cases dropped by 38.4%. Further, more children have access to diversion and prevention programs, totaling 9,319 in 2012. And recidivism dropped to 17.5%!

As Detroit’s woes deepen, the toll on Wayne County’s children will likely increase. But, as Sarri argues, the juvenile justice system initiated in the late 1990s is an investment in the community, rehabilitating youth instead of punishing them for their declining environment.